William Henry Crossland

William Henry Crossland (Huddersfield, May 1835 – London, 14 November 1908)[2][3] was a 19th-century English architect and a pupil of George Gilbert Scott.[2] His architectural works included the design of three buildings that are now Grade I listed – Rochdale Town Hall, Holloway Sanatorium and the Founder's Building at Royal Holloway College.

William Henry Crossland | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 1835 Huddersfield, Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 14 November 1908 (aged 73) London, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouse(s) | Lavinia Cardwell Pigot

(m. 1859; died 1876) |

| Partner(s) | Eliza Ruth Hatt (died 1892) |

| Children | Two (one illegitimate)[1] |

| Buildings |

|

Early life

Born in Huddersfield and baptised on 10 May 1835, he was the younger son of Henry Crossland, a stonemason, and his wife, Eleanor (née Wilkinson).[2] He had an elder brother, James.[4] In the 1850s Crossland became a pupil of George Gilbert Scott.[4] He worked with Scott on the design of the model village Akroydon, near Halifax, West Yorkshire, commissioned by the worsted manufacturer, Edward Ackroyd.

Principal works

Crossland developed his own architectural practice, and worked in Huddersfield, Halifax and Leeds, before moving to Surrey.[5] More than 25 of the buildings he designed are listed by Historic England.[6]

Crossland's three most important commissions, all now Grade I listed, were:

- Rochdale Town Hall, built 1866–71 and still in use as a municipal building in Rochdale, now in Greater Manchester. The Town Hall functions as the ceremonial headquarters of Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council and houses local government departments, including the borough's civil registration office. Art critic Nikolaus Pevsner described the building as possessing a "rare picturesque beauty".[7] Its stained glass windows are credited as "the finest modern examples of their kind".[8] Historic England describe it as "an important early departure from High Victorian heaviness".[9] and it is "widely recognised as being one of the finest municipal buildings in the country".[8] Following a fire, Crossland's original clock tower was replaced in 1887 by a stone clock tower and spire designed by Alfred Waterhouse in the style of Manchester Town Hall.

- Holloway Sanatorium at Virginia Water, Surrey,[3] built 1873–85.[10] This was a project commissioned by the philanthropist Thomas Holloway.[11] Historic England describe it as "the most elaborate and impressive Victorian lunatic asylum in England, because it was the most lavish to be built for private patients... The quality of the external design and the decoration of the principal spaces is exceptional. It is the only example to be listed in grade I."[10] The Sanatorium is preserved and restored, and is now in use as luxury flats. In 1997–98 the site became a gated residential estate, and was renamed Virginia Park.[12]

- The Founder's Building at Royal Holloway College, Egham, Surrey, also commissioned by Thomas Holloway and built 1883–88.[13] It is a short distance away from the Sanatorium. The Founder's Building is now the main building of a major college of the University of London; the bar in the building is named "Crosslands".[14]

The Holloway Sanatorium and Royal Holloway College were inspired by the Cloth Hall of Ypres in Belgium and the Château de Chambord[13] in the Loire Valley, France, respectively and are considered by some to be among the most remarkable buildings in the south of England.

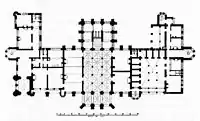

Crossland's plan of Rochdale Town Hall, published in The Builder in 1866

Crossland's plan of Rochdale Town Hall, published in The Builder in 1866 Rochdale Town Hall (1874) with Crossland's original clock tower

Rochdale Town Hall (1874) with Crossland's original clock tower Rochdale Town Hall with tower as rebuilt (1887) to Alfred Waterhouse's design

Rochdale Town Hall with tower as rebuilt (1887) to Alfred Waterhouse's design Holloway Sanatorium, Virginia Water, Surrey (1884). Wood-engraving from the Illustrated London News, 5 January 1884

Holloway Sanatorium, Virginia Water, Surrey (1884). Wood-engraving from the Illustrated London News, 5 January 1884 Holloway Sanatorium

Holloway Sanatorium Royal Holloway College, Egham, Surrey

Royal Holloway College, Egham, Surrey Royal Holloway College

Royal Holloway College

Other commissions

John Elliott provides a catalogue of Crossland's works (based on a compilation by Edward Law which is deposited at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in London).[3] They include many buildings in Yorkshire, some of them listed by Historic England:

Huddersfield

- 1–11 Railway Street and 20–26 Westgate (former Ramsden Estate Office), 1871–72, now Grade II listed[15][16][17]

- 10–18 Westgate and the Byram Arcade, 1880–81, Grade II listed[18][19]

- Bankfield House, Taylor Hill, 1864; unlisted.[20]

- Church of St Andrew, on Leeds Road. The church was built in 1870 and declared redundant in 1975; it is Grade II listed[21]

- Church of St Thomas, Bradley, one of Crossland's earliest commissions,[22] built in 1863–65 and declared redundant in 1975. In listing it at Grade II, Historic England say that the church "is notable for the vitality of detail typical of the decade" and "is carefully sited on sloping ground, with asymmetrical south tower and spire placed so as to maximise the effect of its silhouette".[23][24]

- Kirkgate Buildings, 1878–85; Grade II listed. Commissioned by the Ramsden family who then owned much of Huddersfield, this was a speculative development of office space and shops, originally called Bulstrode Buildings.[6]

- Longley New Hall, 1871–75; Grade II listed. Commissioned by Sir John William Ramsden, it was built as a house for his family, replacing a Tudor building on the same site; it became a school in the 1920s.[25]

- Somerset Buildings, 1883. In listing it at Grade II, Historic England say that "its eclectic C19 Queen Anne styling displays a strong level of architectural flair, incorporating French and Flemish Renaissance influenced detailing to successful effect... it was designed by the notable Huddersfield architect WH Crossland, who has many listed buildings to his name, and is an excellent example of his work... it has strong group value with nearby listed buildings, a number of which were also designed by Crossland".[26]

- Waverley Chambers, 1882, a commercial building which, soon after it was built, became a temperance hotel and later was used as offices; it is now Grade II listed[27]

Byram Arcade in 2007

Byram Arcade in 2007 Former church of St Andrew, Leeds Road

Former church of St Andrew, Leeds Road

Elsewhere in Yorkshire

- Birstall: St Peter's Church, founded in about 1100 and refurbished by Crossland 1863–70. Historic England, listing it at Grade II*, say that it "demonstrates well" Crossland's "preference for the Decorated style and taste for lavish decoration".[28]

- Copley: St Stephen's Church, commissioned by Edward Akroyd and built in 1863; Grade II* listed.[29][30] The church is now redundant and is under the care of the Churches Conservation Trust.[31]

- Elland: Church of St Mary, built mainly in the 13th and 14th centuries and restored by Crossland in 1856; it is listed at Grade I[32]

- Headingley, Leeds: St Chad's Church, Far Headingley, 1868, by Crossland and Edmund Beckett Denison (later 1st Lord Grimthorpe). The church was built on land given by the Beckett family of Kirkstall Grange who paid £10,000 towards it.[33] It is now Grade II* listed.[34]

- Ossett, Wakefield: Church of the Holy Trinity, 1862–65; Grade II* listed[35][36]

- Penistone: Church of St John the Evangelist, 1869; Grade II listed[37]

- Staincliffe: Christ Church, 1867; Grade II listed[38][39]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Christ Church, Staincliffe

Christ Church, Staincliffe

Later life

Crossland disappeared from RIBA records in 1894–95.

Personal life

On 1 October 1859,[3][40] Crossland married Lavinia Cardwell Pigot (who died in 1876).[nb 1] They had one child – a daughter, Maud, born in 1860.[1] Crossland also had an illegitimate son, Cecil Henry Crossland Hatt, with Eliza Ruth Hatt (died 1892), an actress with whom he lived in a bungalow on the Royal Holloway site.[1]

He died in London on 14 November 1908 following a stroke.[2][3] His estate at his death was worth just £29-2s–9d (£29.14). Crossland's wife, his brother James Crossland, his partner Eliza Ruth Hatt, his daughter Maud and his son Cecil are buried at Highgate Cemetery. Although there is a memorial to him at the cemetery, at Crossland's specific request he himself was not buried there.[3] His place of burial is unknown.

Notes

- Although other sources, including her memorial stone at Highgate Cemetery, claim that Crosswell's wife Lavinia died in 1879, Sheila Binns' research demonstrates that this date cannot be correct.

Binns, Sheila (2020). W.H. Crossland: An Architectural Biography. The Lutterworth Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0718895488.

References

- Binns, Sheila (2020). W.H. Crossland: An Architectural Biography. The Lutterworth Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0718895488.

- Elliott, John. Crossland, William Henry. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Elliott, John (1996). Palaces, Patronage & Pills – Thomas Holloway: His Sanatorium, College & Picture Gallery. Egham, Surrey: Royal Holloway, University of London. pp. 17–43. ISBN 0-900145-99-4.

- "William Henry Crossland (1835–1908)". Huddersfield Exposed. 17 September 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Binns, Sheila (2020). W.H. Crossland: An Architectural Biography (PDF). The Lutterworth Press. pp. 11, 32. ISBN 978-0718895488.

- Historic England (29 March 2016). "Kirkgate Buildings (1415453)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Hartwell, Clare; Hyde, Matthew; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2004). Lancashire: Manchester and the South-East,. The Buildings of England. Yale University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-300-10583-5.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council. Metropolitan Rochdale Official Guide. Ed J Burrow & Co. p. 43.

- Historic England (25 October 1951). "Town Hall (1084275)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Historic England (17 November 1986). "Former Holloway Sanatorium at Virginia Water (1189632)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Binns, Sheila (13 October 2020). "Surrey Greats: Who was Royal Holloway architect William H Crossland?". Surrey Life. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Richardson, Harriet (5 March 2016). "Holloway Sanatorium – garish or gorgeous?". Historic Hospitals. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Historic England (17 November 1986). "Royal Holloway College (1028946)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- "Crosslands". Royal Holloway, University of London. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Historic England (29 September 1978). "1–11 Railway Street (1231474)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Historic England (25 March 1977). "20–26 Westgate (1224850)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- "Railway Street: Ramsden Estate Office". Buildings of Huddersfield. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Historic England (29 September 1978). "The Byram Arcade (1224912)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- "Westgate: The Byram Arcade 10–18". Buildings of Huddersfield. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Law, Edward (15 September 2001). "William Henry Crossland, Architect, 1835-1908. Part 5. Buildings 1864-1867". Huddersfield & Distrct History. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- Historic England (29 September 2018). "Former Church of St Andrew (1214957)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Binns, Sheila (2020). W.H. Crossland: An Architectural Biography (PDF). The Lutterworth Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0718895488.

- Historic England (26 April 1976). "Former church of St Thomas (1273979)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- "St. Thomas's Church, Bradley". Huddersfield Exposed. 3 November 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Historic England (8 June 2004). "Longley New Hall (1390979)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Historic England (29 March 2016). "Somerset Buildings (1415451)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Historic England (9 October 2013). "Waverley Chambers (1415452)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Historic England (29 March 1963). "Church of St Peter (1134648)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Historic England (6 June 1983). "Church of St Stephen (1133985)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Binns, Sheila (2020). W.H. Crossland: An Architectural Biography (PDF). The Lutterworth Press. pp. 24–26. ISBN 978-0718895488.

- St Stephen's Church, Copley, West Yorkshire, Churches Conservation Trust, retrieved 18 October 2016

- Historic England (24 January 1988). "Church of St Mary (1184393)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Wrathmell, Susan; Minnis, John (2005). Leeds. Pevsner Architectural Guides. Yale University Press. pp. 260–262. ISBN 0-300-10736-6.

- Historic England (26 September 1963). "Church of St Chad (1375301)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- Historic England (6 May 1988). "Church of the Holy Trinity (1184049)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Binns, Sheila (2020). W.H. Crossland: An Architectural Biography (PDF). The Lutterworth Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0718895488.

- Historic England (27 April 1988). "Church of St John the Evangelist (1315075)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Historic England (13 January 1984). "Christ Church (1134612)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- "Christ Church, Staincliffe Hall Road". Historic England. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Binns, Sheila (2020). W.H. Crossland: An Architectural Biography (PDF). The Lutterworth Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0718895488.

Further reading

- Binns, Sheila (2020). W.H. Crossland: An Architectural Biography. The Lutterworth Press. ISBN 978-0718895488

- Law, Edward (1992). "William Henry Crossland, biography and works". Edward Law. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Henry Crossland. |