William M. Wright

William Mason Wright (September 24, 1863 – August 16, 1943) was a lieutenant general in the United States Army. He was notable for his service as a division and corps commander during World War I.

William M. Wright | |

|---|---|

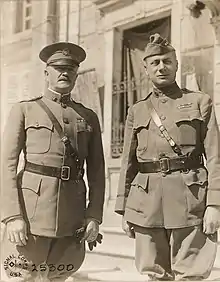

_2.jpg.webp) William M. Wright as Brigadier General | |

| Born | September 24, 1863 Newark, New Jersey |

| Died | August 16, 1943 (aged 79) Walter Reed Army Medical Center |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1885–1923 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | 19th Infantry Regiment Port of Embarkation, Hoboken, New Jersey 35th Division III Corps V Corps VII Corps 89th Division I Corps IX Corps Area Department of the Philippines |

| Battles/wars | Spanish–American War Philippine–American War Veracruz occupation Pancho Villa Expedition World War I |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Medal French Legion of Honor (Commander) French French Croix de Guerre with Palm Belgian Order of Leopold II (Grand Officer) Order of the Rising Sun (Japan) British Order of Saint Michael and Saint George (Commander) |

| Relations | Marjorie Jerauld (wife) (m. 1891) 3 children (including Jerauld Wright) Stevens Thomson Mason (grandfather) William Wright (grandfather) |

The son of a career officer who served as an aide to Winfield Scott and George B. McClellan, Wright initially attracted attention when President Chester A. Arthur nominated him for a second lieutenant's commission despite Wright having failed his exams during his first year as a student at the United States Military Academy, where his roommate was John J. Pershing. Despite the setback, Wright obtained an appointment in the New Jersey National Guard, and served until receiving his Army commission, which was approved in a close vote of the United States Senate; several Senators opposed Arthur's nomination of Wright, arguing that someone who failed at West Point should not receive the same consideration as those who had passed.

Wright embarked on an Army career, and served initially in the western United States. He served for several years as an aide to General John C. Bates, including the Spanish–American War and the Philippine–American War. He later took part in both the Veracruz occupation and Pancho Villa Expedition.

During World War I, Wright commanded several divisions and corps, and took part in combat including the Battle of Saint-Mihiel and the final operations of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, for which he received the Distinguished Service Medal and other decorations.

After the war, Wright served as Executive Assistant to the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, and acted as Chief of Staff on several occasions. He closed his career by serving as head of the Department of the Philippines from 1922 to 1923.

In retirement, Wright lived in Washington, DC. In 1942, Congress passed legislation that enabled promotions on the Army's retired list for general officers who had been recommended for World War I promotions, but had not received them; Wright was one of two major generals to be promoted to lieutenant general. He died in Washington, DC the following year.

Early life

Born in Newark, New Jersey, on September 24, 1863,[1] he was the son of Dora Mason (1839–1916) and Army Colonel Edward H. Wright (1824–1913), a career officer whose service included assignments as aide-de-camp to Generals Winfield Scott and George B. McClellan.[2] William M. Wright was the grandson of Michigan Governor Stevens Thomson Mason and U.S. Senator William Wright of New Jersey.[2] Wright was educated at St. John's School in Ossining, New York (also known as St. John's Military Academy).[3]

He attended Yale University[4] and was a member of the Delta Psi fraternity.[5] In 1882 he left Yale for the United States Military Academy, where his roommate was John J. Pershing.[6] Wright failed his semiannual exams in December 1882 and left West Point in January 1883, resigning before school authorities took action to dismiss him.[7]

Start of career

In 1884, Wright joined the New Jersey National Guard, receiving a captain's commission and appointment as aide-de-camp to the commander of the 1st Brigade.[8]

In January, 1885 he was nominated for appointment as a second lieutenant in the 2nd Infantry Regiment.[9] One of the final acts of outgoing President Chester A. Arthur, Wright's controversial commission received nationwide publicity; it was supported by fellow New Jersey resident Frederick T. Frelinghuysen,[10] the U.S. Secretary of State, and opposed by U.S. Secretary of War Robert T. Lincoln, who argued that someone who had not passed the program of instruction at West Point should not receive the same reward as those who had.[11] His commission was narrowly confirmed by the U.S. Senate in February, 29 votes to 22, meaning that he received his commission more than a year before his peers in the West Point Class of 1886 graduated and received theirs.[12][13]

Wright's initial assignments were with the 2nd Infantry at posts in the western United States, including Fort Spokane, Washington, Fort Omaha, Nebraska, and Fort Coeur d'Alene, Idaho.[14][15] From 1889 to 1891 he attended the School of Infantry and Cavalry at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, after which he rejoined his regiment at Fort Omaha.[16] From 1896 to 1898 Wright was professor of military science at the Massachusetts Agricultural College.[17]

Spanish–American War

Wright served in Cuba during the Spanish–American War.[18] Commissioned as a captain and assistant adjutant general in the U.S. Volunteers, he served in Cuba as aide-de-camp to Major General John C. Bates, commander of the 3rd Division.[19] Wright took part in the Battle of El Caney and the other actions leading to the surrender of Santiago.[20]

In 1899 Wright was promoted to captain in the regular Army.[21] He served in the Philippines during the Philippine–American War, continuing as aide-de-camp to Bates.[22]

Post-Spanish–American War

When Bates returned to the United States in 1901 to take command of the Northern Division of Department of the Missouri, and later the Department of the Lakes, Wright continued to serve as his aide.[23][24]

From 1905 to 1908 Wright served on the Army Staff.[25] In May 1908, he was promoted to major and assigned as adjutant of the 8th Infantry Regiment, then stationed in the Philippines.[26] From 1911 to 1913, Wright served as adjutant of the Philippine Department.[27]

In 1913, Wright was promoted to lieutenant colonel and assigned as second in command of the 19th Infantry Regiment.[28] In 1914 he graduated from the School of Field Officers at Fort Leavenworth.[29] During the next two years he took part in both the Veracruz occupation and Pancho Villa Expedition.[30] In July 1916, Wright was promoted to colonel as commander of the 19th Infantry.[31]

World War I

Commands

At the start of World War I, Wright was promoted to brigadier general and assigned to command the Hoboken, New Jersey Port of Embarkation.[32]

Wright served in France throughout the war, successively commanding the 35th Division,[33] the III,[34] V,[35] and VII Corps[36] (under the French Eighth Army in the Vosges Mountains), the 89th Division[37] (in the Battle of Saint-Mihiel and the final operations of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive), and I Corps,[38] for which he received the Distinguished Service Medal.[39]

Armistice Day attack

On November 11, 1918, Armistice Day, Wright was in command of the 89th Division and carried out an already planned attack against the town of Stenay only a few hours before the armistice was to take effect.[40] There were 365 casualties, including 61 dead.[41] One rationale for the attack was that he did not want the Germans to occupy the town after the armistice took effect, because Wright intended to make use of the town's bathhouses and other public works, given the amount of time his dirty troops had gone so long without baths or showers.[42] Detractors suggested Wright wanted to capture Stenay because it had cachet as the recent headquarters of Prince Rupprecht, a senior commander of German troops.[43] Another reason offered by Wright in testimony before Congress was that commanders had not been informed how long the armistice would be in effect; several continued with already planned attacks in order to improve their tactical positions, so that they could operate from a position of advantage if hostilities resumed.[44] Yet another rationale was provided by Fox Conner; in his Congressional testimony, Conner indicated that at the time of the armistice, severe bad weather was expected; since Stenay was one of the few towns in the area with large buildings still standing, Conner and other American Expeditionary Forces headquarters staff wanted to occupy the town so the buildings could be used for quartering troops.[45] In addition, those who questioned Wright's decision to carry out the 89th Division's attack pointed to a rivalry with Henry Tureman Allen, commander of the adjacent 90th Division, who also attempted to capture Stenay.[46] When it became clear that Wright and other senior commanders had ordered assaults with full knowledge that the Armistice would go into effect imminently, Allied soldiers and civilians became outraged;[47] there was controversy, but commanders, including Wright, were never punished or reprimanded.[48]

Journal

During World War I Wright kept a journal, which was later published as Meuse-Argonne Diary: A Division Commander in World War I.[49]

Post–World War I

.jpg.webp)

Following the war, General Wright served as Executive Assistant to Peyton C. March, the Chief of Staff of the United States Army,[50] and acting Army Chief of Staff.[51] He then commanded IX Corps Area.[52] In 1922, he was assigned to command the Department of the Philippines, and he retired in 1923.[53][54]

Retirement, death and burial

In retirement he resided in Washington, D.C.[55][56]

In 1942, the U.S. Congress passed legislation allowing retired Army generals to be advanced one rank on the retired list or posthumously if they had been recommended in writing during World War I for a promotion which they did not receive, and if they had received the Medal of Honor, the Distinguished Service Cross or the Distinguished Service Medal.[57] Wright and James G. Harbord were promoted to lieutenant general on July 9, 1942.[58]

General Wright died at Washington, D.C.'s Walter Reed Army Hospital on August 16, 1943,[59] and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 2, Grave 4956-NH.[60][61]

Awards

- Distinguished Service Medal

- Spanish Campaign Medal

- Philippine Campaign Medal

- Mexican Service Medal

- World War I Victory Medal

- Grand Officer of the Order of Leopold II (Belgium)[62]

- Commander of the Legion of Honor (France)[63]

- Croix de Guerre with Palm (France)[64]

- Commander of the Order of Saint Michael and Saint George (United Kingdom)[65]

- Order of the Rising Sun (Japan)[66]

Citation for Distinguished Service Medal

"For exceptionally meritorious and distinguished services. He commanded in turn the Thirty-fifth Division; the Third, Fifth, and Seventh Army Corps, under the Eighth French Army in the Vosges Mountains, and later commanded the Eighty-ninth Division in the St. Mihiel offensive and in the final operations on the Meuse River, where he proved himself to be an energetic and aggressive leader."

General Order 12 (January 17, 1919)[67]

Reputation

Wright was a highly regarded trainer of soldiers and combat leader.[68] In his memoirs, Pershing indicated that Wright left West Point only because he had difficulty passing geometry, and that his classmates approved of Wright obtaining his commission through an alternate route, even though he received his before they received theirs.[69] Pershing also commended Wright's leadership during World War I, as did former Army Chief of Staff Leonard Wood and senior British commander Field Marshal Douglas Haig.[70]

Family

In June 1891, Wright married Marjorie Jerauld.[71] They were the parents of: Colonel William Mason Wright, Jr. (1893–1977), who served in France during World War I, in the China Burma India Theater during World War II, and commanded the Armed Forces Education and Information Service and the Armed Forces Radio Service during and after World War II;[72] Admiral and U.S. Ambassador to the Republic of China (Taiwan) Jerauld Wright (1898–1995);[73][74] and Marjorie Wright (1900-1985), who married David McK. Key, and worked for the United States Department of State as a cultural affairs assistant and in other positions.[75][76]

References

- Hall, Edward Hagaman (1899). Register of the Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. New York, NY: Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. p. 352.

- Committee on Printing (1908). Third Record Book of the National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of Rhode Island. Providence, RI: Snow & Farnham Co. p. 385 – via Google Books.

- The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. Current Volume A. New York, NY: James T. White & Company. 1930. p. 440.

- The Yale Pot-pourri. XVII. New Haven, CT: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor. 1881. p. 42.

- Catalogue of the Members of the Fraternity of Delta Psi. New York, NY: Fraternity of Delta Psi. 1889. p. 192.

- Pershing, John J. (2013). My Life Before the World War, 1860–1917: A Memoir. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0-8131-4197-8.

- "Military Academy". Army and Navy Journal. New York. January 13, 1883. p. 528.

- New Jersey Adjutant General (1884). Annual Report. Trenton, NJ: John L. Murphy, State Printer. p. 15.

- "Appointments to the Army". New York Times. New York Times. January 22, 1885. p. 1.

- "Unpopular Appointments: Unfavorable Criticism Provoked by the Actions of the President". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. January 23, 1885. p. 6.

- "Appointments to the Army"

- Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States. 24. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. 1901. p. 469.

- "Condensed News: William M. Wright". Freeport Journal. Freeport, Illinois. January 22, 1885. p. 3.

- "The Army: The Line; 2nd Infantry, Colonel Frank Wheaton". Army and Navy Journal. New York, NY. May 8, 1886. p. 830.

- "Obituary, William M. Wright". Army and Navy Journal. New York, NY. August 21, 1943. p. 1513.

- Lyons, Norbert (April 1, 1922). "Major General William M. Wright". The American Chamber of Commerce Journal. Manila, Philippines: American Chamber of Commerce of the Philippine Islands. p. 108.

- Massachusetts Agricultural College (1898). Annual Report. Boston, MA: Wright & Potter. p. 19.

- Register of the Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution

- Clerk, U.S. Congress Joint Committee on Printing (1899). The Abridgment: Containing Messages of the President of the United States to the Two Houses of Congress. III. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. p. 276.

- Register of the Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution

- Register of the Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution

- U.S. Army Adjutant General (1901). U.S. Army Register. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. p. 309.

- "The Army: Department of the Missouri; Northern Division". Army and Navy Register. New York, NY: Army and Navy Publishing Company. January 30, 1904. p. 18.

- U.S. Army Adjutant General (1904). U.S. Army Register. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. p. 438.

- American Chamber of Commerce Journal

- American Chamber of Commerce Journal

- American Chamber of Commerce Journal

- American Chamber of Commerce Journal

- United States House of Representatives (1920). Hearing Record: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Foreign Expenditures of the Select Committee on Expenditures in the War Department. 2. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. p. 1747.

- American Chamber of Commerce Journal

- American Chamber of Commerce Journal

- American Chamber of Commerce Journal

- Thomas, Shipley (1920). The History of the A. E. F. New York, NY: George H. Doran Company. p. 465.

- "America's First Field Army". The European War. The New York Times. The New York Times Current History. XVI. 1918. p. 429.

- Skillman, Willis Rowland (1920). The A.E.F.: Who They Were, What They Did, How They Did It. Philadelphia, PA: George W. Jacobs & Company. p. 54.

- The A.E.F.: Who They Were, What They Did, How They Did It. p. 57.

- English, George H., Jr. (1920). History of the 89th Division, U.S.A. Denver, CO: Smith-Brooks Printing Company. p. 17.

- American Chamber of Commerce Journal

- U.S. Army Adjutant General (1920). The Congressional Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross and the Distinguished Service Medal Issued by the War Department Since April 6, 1917. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. p. 1000.

- Persico, Joseph E. (2005). Eleventh Month, Eleventh Day, Eleventh Hour: Armistice Day, 1918; World War I and its Violent Climax. New York, NY: Random House. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-375-76045-7.

- Flank, Lenny (November 11, 2015). "The Last Day of World War One". Daily Kos. Oakland, CA: Kos Media, LLC.

- Eleventh Month, Eleventh Day, Eleventh Hour: Armistice Day, 1918

- Eleventh Month, Eleventh Day, Eleventh Hour: Armistice Day, 1918

- United States House of Representatives (1920). Hearing Record: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Foreign Expenditures of the Select Committee on Expenditures in the War Department. 2. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. p. 1741.

- Hearing Record: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Foreign Expenditures. p. 1736

- Eleventh Month, Eleventh Day, Eleventh Hour: Armistice Day, 1918

- Ferrell, Robert H. (2007). America's Deadliest Battle: Meuse-Argonne, 1918. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-7006-1499-8.

It was sickening and depressing to hear officers like Brigadier General Fox Conner (West Point, 1898), my classmate, tell of the importance of our gaining a certain ridge or section of ground before the Armistice went into effect. What did these useless killings and injuries mean to officers who had never commanded men in battle, whose entire war experience was a war on paper, where the expenditure of human life was necessary, but with which they had no experience, no responsibility, and apparently little sympathy.

(Colonel Conrad S. Babcock, commander, 354th Infantry Regiment, 177th Infantry Brigade, 89th Division) - Persico, Joseph E. (June 12, 2006). "World War I: Wasted Lives on Armistice Day". Historynet.com. Tysons, VA: World History Group.

- Wright, William Mason (2004). Meuse-Argonne Diary: A Division Commander in World War I. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1527-7.

- March, Peyton C. (1920). Annual Report of the Chief of Staff of the Army to the Secretary of War. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. p. 19.

- War Department Bulletins. 2. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. 1920. p. 72.

- "General Wright is Welcomed by Community". San Francisco Business. July 29, 1921. p. 22.

- "Morton Takes Over Ninth Corps Area". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco, CA. January 31, 1922. p. 9.

- "Major-General Wright Retired". Indianapolis News. Indianapolis, IN. January 1, 1923. p. 30.

- Gebhart, John Charles (1930). Prohibition Enforcement: Its Effect on Courts and Prisons. Washington, DC: Association Against the Prohibition Amendment. p. 32.

- "Wm. M. Wright in the 1940 United States Federal Census". Ancestry.com. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com, LLC. 1940.

- "Seven Generals Get Belated Boosts in Rank". Salt Lake Tribune. Salt Lake City, UT. Associated Press. July 12, 1942. p. 7.

- "Retired Generals Promoted". Army and Navy Journal. New York, NY. July 25, 1942. p. 1316.

- "Gen. William Wright Dies; Veteran of Two Wars". The Evening Star. Washington, DC. August 17, 1943. p. 10.

- "Burial Record, William Mason Wright". Arlington National Cemetery. Washington, DC: United States Department of the Army. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- Army and Navy Journal. 80. New York, NY: Army and Navy Publishing Company. 1943. p. 1513.

- "Gen. William Wright Dies; Veteran of Two Wars"

- English, George H., Jr. (1920). History of the 89th Division, U.S.A. Smith-Brooks Printing Company: Denver, CO. p. 390.

- "Gen. William Wright Dies; Veteran of Two Wars"

- History of the 89th Division, U.S.A. p. 392

- "Gen. William Wright Dies; Veteran of Two Wars"

- "Distinguished Service Medal Citation, William Mason Wright". Hall of Valor. Vienna, VA: Military Times. January 17, 1919.

- Palmer, Frederick (1919). Our Greatest Battle (The Meuse-Argonne). New York, NY: Dodd, Mead and Company. p. 180.

- Pershing, John J. (2013). My Life Before the World War, 1860--1917: A Memoir. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0-8131-4197-8.

- Ossad, Stephen L.; Marsh, Don R. (2003). Major General Maurice Rose: World War II's Greatest Forgotten Commander. Latham, NY: Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-87833-308-0.

- Who Was Who In American History: The Military. Chicago, IL: Marquis Who's Who, Inc. 1975. p. 649. ISBN 9780837932019.

- Taylor, Mary S. (September 27, 1977). "Obituary: Wright, William Mason Jr. 1893-1977". Monterey Peninsula Herald. Monterey, CA. CAGenWeb, Monterey County Genealogy. p. 4. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "NATO Chief Was Army Brat". The Daily Notes. Canonsburg, PA. United Press International. April 2, 1959. p. 14.

- Pearson, Richard (April 28, 1995). "Adm. Jerauld Wright Dies". Washington, DC. Washington, DC.

- "David McK. Key, 88, A Former Ambassador". New York Times. New York, NY. July 17, 1988.

- Foreign Service List. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. 1946. p. 34.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William M. Wright. |