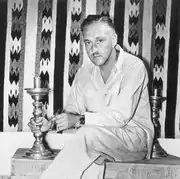

William Spratling

William Spratling (September 22, 1900 – August 7, 1967) was an American-born silver designer and artist, best known for his influence on 20th century Mexican silver design.

Early life

Spratling was born in 1900 in Sonyea, Livingston County, New York, the son of epileptologist William P. Spratling. After the deaths of Spratling's mother and sister, he moved to his father's boyhood home outside of Auburn, Alabama. Spratling graduated from Auburn High School and the Alabama Polytechnic Institute (currently known as Auburn University), where he majored in architecture.

Career

Architecture professor and lecturer

Upon graduation, Spratling took a position as an instructor in the architecture department at Auburn University, and in 1921 he was offered a similar position at Tulane University's School of Architecture in New Orleans, Louisiana.[1] At the same time, he was an active participant in the Arts and Crafts Club and taught in the New Orleans Art School.

During the summers of 1926-1928, Spratling lectured on colonial architecture at the National University of Mexico's Summer School.[2]

Taller de las Delicias

The highly charged political and social environment in Mexico after the revolution influenced Spratling's decision in 1931 to reestablish a silver industry in Taxco.[3][nb 1] Taxco was a traditional site of silver mines, but had no native silverworking industry. Spratling began designing works in silver based primarily on pre-Columbian and traditional motifs, and hired local goldsmiths to produce those designs in Taxco. Spratling was the primary designer for his workshop, Taller de las Delicias, and was insistent on the high quality of the materials and techniques used in production. Talented maestros shared in the creative dialogue with Spratling, transforming his design drawings into prototypes in silver.[nb 2]

Spratling's use of an aesthetic vocabulary based on pre-Columbian art can be compared to the murals of Diego Rivera, in that both artists were involved in the creation of a new cultural identity for Mexico. Primarily, Spratling's silver designs drew upon pre-conquest Mesoamerican motifs, with influence from other native and Western cultures. To many, his work served as an expression of Mexican nationalism, and gave Mexican artisans the freedom to create designs in non-European forms. Because of his influence on the silver design industry in Mexico, Spratling has been called the "Father of Mexican Silver".

The forms that evolved in silver at Las Delicias were admired by visitors to the workshop, who purchased the objects as talismans of a remote and exotic culture.

Wholesale

In the late thirties, Spratling expanded beyond sales at Las Delicias and into a wholesale business. He employed over 500 artisans in the workshop to meet the demand in the United States for luxury good during World War II. Spratling silver was sold through the Montgomery Ward catalog and at Neiman Marcus and Saks Fifth Avenue. With the cost of moving the workshop to an ancient silver hacienda, La Florida, Spratling incorporated to provide cash flow for his company. On June 30, 1945, a majority of the shares was sold to North American investor Russell Maguire, whose business practices ultimately took the company into bankruptcy.[4]

Alaska Native Arts

Spratling had received widespread notoriety as a result of his development of what many considered a model handwrought industry. In 1945, Spratling was asked by two friends, Alaska's Territorial Governor, Ernest Gruening, and the Director of the Indian Arts and Crafts Board, Rene d'Harnoncourt, to replicate his success in Alaska.[5] Spratling recommended the establishment of workshop and exhibit centers in various regions of Alaska organized into a Federation of Alaska Native Arts. Each center's unique production would be born out of the traditions in iconography, materials, and techniques belonging to that specific region.[6] In 1948, Alaskan World War II veterans were sent to Taxco for instruction in silversmithing. Spratling also produced 200 prototypes as future inspiration for the newly trained Alaskans in their workshop centers.[7] Unfortunately, Congress did not allocate funds and the project was not implemented.

Taxco workshop

In 1952, Spratling reestablished a small workshop at his ranch in Taxco el Viejo and began production of silver jewelry and decorative objects that clearly were influenced by his Alaskan experience. In a 1955 article, "25 Years of Mexican Silverware," Spratling expressed his belief that the object in silver should be considered the culmination of a mystical and visionary process.[8] For Spratling, the necessity of direct human involvement in every phase of a handwrought industry meant there were contributions to be made by every maestro and silversmith. The designer continuously interacted with and was aware of the capabilities of members of the workshop. The final statement, the object itself, was a result of an ongoing experiment in creativity.

Silver works

Spratling's earliest work can be characterized as inspired expressions in silver, resembling the power of the reliefs on the Temple of Quetzalcoatl at Xochicalco or the pre-Columbian clay stamps he admired.[9] The designs incorporate sinuous lines that were deeply carved, with strong light and shadow contrasts. The inspiration from pre-Columbian models could be direct, as in the repousse Quetzalcoatl brooch, based on the heart bowl in the Museo Nacional de Antropología, or indirect, like the silver pitcher with the eagle handle in carved wood.[10]

Spratling marked his earliest work with a simple interlocking WS. After 1938, he began using a circular mark with the WS sans-serifs at its center, around which read "Spratling Made in Mexico". This mark was accompanied, up until 1945, with an oval in which was imprinted, "Spratling Silver". The Alaska pieces and work from c. 1950 were marked with a simple script "WS". Spratling also collaborated briefly (1949–51) with the Mexico City silver company Conquistador, and these pieces were marked with a circle in which was inscribed "Spratling de [or of] Mexico" and across, "Sterling". The eagle or assay mark for the Conquistador pieces contained the number 13, and for Spratling, the numbers 1 or 30.[11]

Spratling's later work is more linear and refined. The croissant necklace has a great deal of movement, but now based on abstract form. Spratling's maker's mark in this period once again took the form of a circle, this time with the script "WS" surrounded by the words, "William Spratling Taxco Mexico". In the 1960s, Spratling began producing jewelry in gold with pre-Columbian stones. Each piece was unique and marked with a simple "WS" beneath "18K".[12]

Published works

- In 1926 Spratling collaborated with William Faulkner on Sherwood Anderson And Other Famous Creoles, a series of caricatures depicting the bohemian atmosphere of artists and writers living and working in the French Quarter in the 1920s.[13]

- In 1927, Spratling did illustrations for his good friend Natalie Scott's Old Plantation Houses in Louisiana. The balanced interaction between illustration and text was characteristic of all of Spratling's published work. In Plantation Houses, the renderings of the buildings are as descriptive as Natalie Scott's narrative, which, when taken together, transport the reader into settings where people lived out their lives.[14]

- In a 1928 article for Scribner's Magazine, Spratling had sensitively portrayed the people of Isle Breville, Louisiana.[15]

- Little Mexico was published in 1932 and is considered his most significant literary work.[2] The same qualities of observation by Spratling for the 1928 articles are present and compelling in Little Mexico. In the following passage, Spratling comes close to defining the intensity of his encounters: "To rub shoulders with the Indian population, to see them smiling and occupied, eating their simple meals, arguing agrarian problems over a cup of tequila, arranging themselves on the ground for the night, and, above all, to witness their dances and to observe the mystery of the faces of the dancers - is a profound experience."[16]

Personal life

While teaching at Tulane, Spratling shared a house with writer William Faulkner.[13]

When lecturing at the National University of Mexico's Summer School in 1926-1928, Spratling quickly integrated himself into the Mexican art scene and became a friend and a strong proponent of the work of muralist Diego Rivera, for whom he organized an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Using money received from commissions he organized for Rivera, Spratling bought a home in Taxco, Mexico in 1928, where he began work on a book, Little Mexico, about this small mountain town.[2]

Spratling was gay, but most accounts of his life mention this only indirectly if at all.[17][18]

Spratling amassed a large collection of pre-Columbian figurines from Remojadas, Veracruz, which he donated, in large part, to the museum of the National Autonomous University of Mexico in 1959. Photographed by Manuel Álvarez Bravo, several of these works were published in More Human Than Divine.[19] Spratling also donated hundreds of pre-Columbian objects to a museum in Taxco that today bears his name.[20]

Standing Figure with Elaborate Costume Holding Rattles, 300 BC-AD 300 (Late Pre-Classic), previously in Spratling's collection, now at Walters Art Museum.

Standing Figure with Elaborate Costume Holding Rattles, 300 BC-AD 300 (Late Pre-Classic), previously in Spratling's collection, now at Walters Art Museum. Tripod Vase, between 250 and 600 (Early Classic), previously in Spratling's collection, now at Walters Art Museum.

Tripod Vase, between 250 and 600 (Early Classic), previously in Spratling's collection, now at Walters Art Museum.

Death

Spratling was killed in an automobile accident outside of Taxco on August 7, 1967, at the age of 66.[21] Sabina Leof (aka Tibby Leof, wife of noted Pre-Columbian art collector and preeminent dentist Dr Milton Arno Leof) commented on her friendship with Spratling: "He had no political views, was not dedicated to anything special. He believed in humanity. He was an ardent American, but had a great love for the Mexican people."[22][nb 3]

Notes

- He wrote: "The idea was to utilize the silver from Taxco in the production of Mexican articles in silver which could be sold and which would produce a livelihood for several. Taxco had been producing silver for 400 years without benefiting its own people."[3]

- In large part, Spratling's success depended on the workshop setting, which was self-governing, and where advancement was based on ability and accomplishment. Beyond the workshop, the men who learned to speak English had direct contact with the clients in the store. Those who had a penchant for business were in the front office, keeping the books. Las Delicias then developed into a tightly interconnected and interdependent community of artisans, salesmen, and administrators. Within the structure, young men of very modest means with only a rudimentary education could be trained and could excel.

- Immediately after his death, several of Spratling's close friends were asked to give some sense of his genius as an artist and designer, as well as the kind of person he was. The artist Helen Escobedo considered him paradoxical and difficult to know: "He retreated into the countryside and met people only when he wanted to. He was generous but very aware of money. A brilliant salesman, but could also be rude. People loved him and disliked him. Although he was isolated in Taxco he was always au jour. The man was an adventurer, and nothing was too much for him. An explorer and a yachtsman, he went through two or three airplanes. He just couldn't squeeze enough out of life. He was an extraordinary character. He made his own rules. He was a rough diamond and never attempted to polish it. His charm consisted in his being ridiculously generous, extremely interesting,...a storyteller. "His silver gave him the two things he wanted: his passion for liberty, and his passion for collecting pre-Columbian things. His silversmiths respected him. They knew he knew his job. They understood him because he thought in their ways. He was kind to them but always in a gruff manner. They knew they could rely on him. And he never expected thanks for what he did. "He was a legend in his own time. He was a citizen of the world at home everywhere in his very personal way."

See also

References

- William Spratling, File on Spratling (Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown and Company, 1967): 6-8.

- William Spratling, Little Mexico, New York: Jonathan Cape and Harrison Smith, 1932.

- William Spratling, "25 Years of Mexican Silverware", Artes de Mexico, Vol. III, No. 10 (1955): 88

- Penny C. Morrill and Carole A. Berk, Mexican Silver: 20th Century Handwrought Jewelry and Silver (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 4th edition, 2007): 50-54

- William Spratling, File on Spratling (Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown and Company, 1967): 126-140; Penny C. Morrill and Carole A. Berk, Mexican Silver: 20th Century Handwrought Jewelry and Silver (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 4th Edition, 2007): 54-56, 60-67

- Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. RG 75. Box no. 78. Location 04/02/10(6). General Subject Correspondence, 1933-1963, Files 950-969. File 969: Spratling. National Archives, Juneau Area Office. Report: A Plan for Organizing the Crafts and Smaller Industries (all Manual or Semi-Manual Production) and a Policy for their Constant Future Development in Alaska, Oct. 1945

- RG 75, File 969. Spratling to Tony Polet, Oct. 26, 1948; Foster to Gov. Gruening, Nov. 8, 1948; Foster to William Zimmerman, Nov. 10, 1948. These prototypes are now in the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian and the Alaska State Museum. See Penny C. Morrill, editor and author, Maestros de Plata: William Spratling and the Mexican Silver Renaissance {Harry N. Abrams, Inc., with the San Antonio Museum of Art, 2002}: 38-39

- William Spratling, "25 Years of Mexican Silverware," Artes de Mexico, Vol. III, No. 10 (1955): 90

- Spratling sent his friend, Tulane University archaeologist Frans Blom, imprints of his clay stamps in 1938. These are housed in the Latin American Library at Tulane University. See also Penny C. Morrill, editor and author, Maestros de Plata: William Spratling and the Mexican Silver Renaissance {Harry N. Abrams, Inc., with the San Antonio Museum of Art, 2002}: 24.

- Penny C. Morrill, editor and author, Maestros de Plata: William Spratling and the Mexican Silver Renaissance {Harry N. Abrams, Inc., with the San Antonio Museum of Art, 2002}: 167.

- Penny C. Morrill, editor and author, Maestros de Plata: William Spratling and the Mexican Silver Renaissance {Harry N. Abrams, Inc., with the San Antonio Museum of Art, 2002}: 255-256 for Spratling's maker's marks. Another source of information for Spratling's marks is the website, "Spratling Silver", authored by Phyllis Goddard: http://www.spratlingsilver.com/.

- Drawings for a number of these unique gold jewelry designs are now in the Spratling-Taxco Collection in Tulane University's Latin American Library.

- William Spratling, File on Spratling (Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown and Company, 1967): 13, 16-30, 34-35; William Spratling and William Faulkner, Sherwood Anderson and Other Famous Creoles, New Orleans, 1926; Penny C. Morrill and Carole A. Berk, Mexican Silver: 20th Century Handwrought Jewelry and Silver (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 4th edition, 2007): 17-18; 256-257.

- Natalie Scott and William Spratling, Old Plantation Houses in Louisiana, New York: William Helburn, Inc., 1927. Also see John W. Scott, Natalie Scott: A Magnificent Life, Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Co., 2008

- William Spratling, "Cane River Portraits", Scribner's Magazine, Vol. LXXXIII, No. 1 (January 1928): 411-418.

- William Spratling, Little Mexico, New York: Jonathan Cape and Harrison Smith, 1932, 69, 84-5

- Mark, Joan (2000). The Silver Gringo: William Spratling and Taxco. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 16, 39, 115. ISBN 0-8263-2079-1.

- Ochsner, Jeffrey (2007). Lionel H. Pries, Architect, Artist, Educator: From Arts and Crafts to Modern Architecture. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. pp. 103–5. ISBN 978-0-295-98698-2.

- William Spratling, More Human than Divine: An Intimate and Lively Self-Portrait in Clay of a Smiling People from Ancient Vera Cruz (Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, 1960): 11-13

- Valtierra, Angel. "Fin de Semana in Taxco" (in Spanish). Mexico Desconocido. Archived from the original on 2010-03-10. Retrieved 2009-08-26.

- "Famed Silversmith Killed in Auto Crash", Chicago Tribune, August 8, 1967, p3

- Mary Daniels, "The Many Sides of William Spratling," The News, Mexico, D.F. (week of Aug. 20, 1967): 11b-13b

Further reading

- Goddard, Phyllis M., Spratling Silver: A Field Guide, Keenan Tyler Paine, Altadena CA 2003

- Littleton, Taylor D. The Color of Silver: William Spratling, His Life and Art, Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge 2000

- Morrill, Penny C., William Spratling and the Mexican Silver Renaissance: Maestros de Plata, Harry N. Abrams, New York; San Antonio Museum of Art, San Antonio 2002

- Morrill, Penny Chittim, and Berk, Carole A., Mexican Silver: 20th Century Handwrought Jewelry & Metalwork, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, PA 1994

- Reed, John Shelton, "The Man from New Orleans," Oxford American, November/December 2000: 102–107

- Spratling, William, File on Spratling: An Autobiography, Little, Brown and Company, Boston 1967