Women's Army Corps

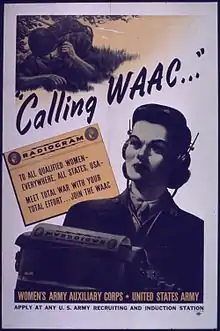

The Women's Army Corps (WAC) was the women's branch of the United States Army. It was created as an auxiliary unit, the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) on 15 May 1942 by Pub.L. 77–554,[1] and converted to an active duty status in the Army of the United States as the WAC on 1 July 1943. Its first director was Oveta Culp Hobby, a prominent woman in Texas society.[2][3] The WAC was disbanded in 1978, and all units were integrated with male units.

| Women's Army Corps | |

|---|---|

Pallas Athene, official insignia of the U.S. Women's Army Corps | |

| Active | 1942–1978 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Home station | Fort McClellan, Alabama |

| Branch colour | Mosstone Green and Old Gold Piping |

| Engagements | World War II Korean War Vietnam War |

History

The WAAC's organization was designed by numerous Army bureaus coordinated by Lt. Col. Gillman C. Mudgett, the first WAAC Pre-Planner; however, nearly all of his plans were discarded or greatly modified before going into operation because he expected a corps of only 11,000 women.[4] Without the support of the War Department, Representative Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts introduced a bill on 28 May 1941, providing for a women's army auxiliary corps. The bill was held up for months by the Bureau of the Budget but was resurrected after the United States entered the war. The senate approved the bill on 14 May 1941 and became law on 15 May 1942.[5] When President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the bill the next day, he set a recruitment goal of 25,000 women for the first year. That goal was unexpectedly exceeded, so Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson decided to increase the limit by authorizing the enlistment of 150,000 volunteers.[6]

The WAAC was modeled after comparable British units, especially the ATS, which caught the attention of Chief of Staff George C. Marshall.[7] Members of the WAC became the first women other than nurses to serve within the United States Army.[8] In 1942, the first contingent of 800 members of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps began basic training at Fort Des Moines Provisional Army Officer Training School, Iowa. The women were fitted for uniforms, interviewed, assigned to companies and barracks and inoculated against disease during the first day.[9]

The WAAC were first trained in three major specialties. The brightest and nimblest were trained as switchboard operators. Next came the mechanics, who had to have a high degree of mechanical aptitude and problem solving ability. The bakers were usually the lowest scoring recruits and were stereotyped as being the least intelligent and able by their fellow WAACs. This was later expanded to dozens of specialties like Postal Clerk, Driver, Stenographer, and Clerk-Typist. WAC armorers maintained and repaired small arms and heavy weapons that they were not allowed to use.

A physical training manual titled "You Must Be Fit" was published by the War Department in July 1943, aimed at bringing the women recruits to top physical standards. The manual begins by naming the responsibility of the women: "Your Job: To Replace Men. Be Ready To Take Over."[10] It cited the commitment of women to the war effort in England, Russia, Germany and Japan, and emphasized that the WAC recruits must be physically able to take on any job assigned to them. The fitness manual was state-of-the-art for its day, with sections on warming up, and progressive body-weight strength-building exercises for the arms, legs, stomach, and neck and back. It included a section on designing a personal fitness routine after basic training, and concluded with "The Army Way to Health and Added Attractiveness" with advice on skin care, make-up, and hair styles.[10]

Inept publicity and the poor appearance of the WAAC/WAC uniform, especially in comparison to that of the other services, handicapped recruiting efforts. A resistance by senior Army commanders was overcome by the efficient service of WAACs in the field, but the attitude of men in the rank and file remained generally negative and hopes that up to a million men could be replaced by women never materialized. The United States Army Air Forces became an early and staunch supporter of regular military status for women in the army.[6]

About 150,000[11] American women eventually served in the WAAC and WAC during World War II. They were the first women other than nurses to serve with the Army.[12] While conservative opinion in the leadership of the Army and public opinion generally was initially opposed to women serving in uniform, the shortage of men necessitated a new policy.

While most women served stateside, some went to various places around the world, including Europe, North Africa, and New Guinea. For example, WACs landed on Normandy Beach just a few weeks after the initial invasion.[13]

Slander campaign

In 1943 the recruiting momentum stopped and went into reverse as a massive slander campaign on the home front challenged the WACs as sexually immoral.[14] Many soldiers ferociously opposed allowing women in uniform, warning their sisters and friends they would be seen as lesbians or prostitutes.[15] Other sources were from other women - servicemen's and officer's wives' idle gossip, local women who disliked the newcomers taking over "their town", female civilian employees resenting the competition (for both jobs and men), charity and volunteer organizations who resented the extra attention the WAACs received, and complaints and slander spread by disgruntled or discharged WAACs.[16] All investigations showed the rumors were false.[17][18]

Although many sources spawned and fed bad jokes and ugly rumors about military women,[19] contemporaneous[20][21] and historical[22][23] accounts have focused on the work of syndicated columnist John O'Donnell. According to an Army history, even with its hasty retraction,[24] O'Donnell's 8 June 1943 "Capitol Stuff" column did "incalculable damage."[25] That column began, "Contraceptives and prophylactic equipment will be furnished to members of the WAACS, according to a super secret agreement reached by the high ranking officers of the War Department and the WAAC chieftain, Mrs. William Pettus Hobby…."[26] This followed O'Donnell's 7 June column discussing efforts of women journalists and congresswomen to dispel "the gaudy stories of the gay and careless way in which the young ladies in uniform … disport themselves…."[27]

The allegations were refuted,[21][28][29] but the "fat was in the fire. The morals of the WAACs became a topic of general discussion…."[30] Denials of O'Donnell's fabrications[23] and others like them were ineffectual.[31] According to Mattie Treadwell's Army history, as long as three years after O'Donnell's column, "religious publications were still to be found reprinting the story, and actually attributing the columnist's lines to Director Hobby. Director Hobby's picture was labeled 'Astounding Degeneracy' …."[32]

Women of color

Black women served in the Army's WAAC and WAC, but very few served in the Navy.[33] African American women serving in the WAC experienced segregation in much the same fashion as in U.S. civilian life. Some billets accepted WACs of any race, while others did not.[34] Black women were taught the same specialties as white women, and the races were not segregated at specialty training schools. The US Army goal was to have 10 percent of the force be African-American, to reflect the larger U.S. population, but a shortage of recruits brought only 5.1 percent black women to the WAC.[35]

Evaluations

General Douglas MacArthur called the WACs "my best soldiers", adding that they worked harder, complained less, and were better disciplined than men.[36] Many generals wanted more of them and proposed to draft women but it was realized that this "would provoke considerable public outcry and Congressional opposition", and so the War Department declined to take such a drastic step.[37] Those 150,000 women who did serve released the equivalent of 7 divisions of men for combat. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower said that "their contributions in efficiency, skill, spirit, and determination are immeasurable".[38] Nevertheless, the slander campaign hurt the reputation of the WAC and WAVES; many women did not want it known they were veterans.[39]

During the same time period, other branches of the U.S. military had similar women's units, including the Navy WAVES, the SPARS of the Coast Guard, United States Marine Corps Women's Reserve, and the (civil) Women Airforce Service Pilots. The British Armed Forces also had similar units, including the Women's Royal Naval Service ("Wrens"), the Auxiliary Territorial Service. and the Women's Auxiliary Air Force.

According to historian D'Ann Campbell, American society was not ready for women in military roles:

- The WAC and WAVES had been given an impossible mission: they not only had to raise a force immediately and voluntarily from a group that had no military traditions, but also had overcome intense hostility from their male comrades. The situation was highly unfavorable: the women had no clear purpose except to send men to the battlefront; duties overlapped with civilian employees and enlisted male coworkers, causing confusion and tension; and the leadership cadre was unprestigious, inexperienced, and had little control over women, none over men. Although the military high command strongly endorsed their work, there were no centers of influence in the civilian world, either male or female, that were committed to the success of the women's services, and no civilian institutions that provided preliminary training for recruits or suitable positions for veterans. Wacs, Waves, Spars and women Marines were war orphans whom no one loved.[40]

Manhattan Project

Wacs were assigned to the Corps of Engineers since early 1943. Four-hundred twenty-two personnel were employed on the project. Maj. Gen. Leslie R. Groves, commander of the project, wrote: "Little is known of the significance of the contribution to the Manhattan Project by hundreds of members of the Women's Army Corps ... Since you received no headline acclaim, no one outside the project will ever know how much depended upon you."

The women interviewed for positions on the project were told they would do a hard job, would never be allowed to go overseas or attend officer candidate school, would never receive publicity, and would live at isolated stations with few recreational facilities. A surprising number of highly qualified women responded.

WAC units involved in this effort were awarded the Meritorious Unit Service Award; twenty women received the Army Commendation Ribbon; and one received the Legion of Merit.[41] In addition, all members of the WAAC and the WAC who served in World War 2 received the Women's Army Corps Service Medal.

Disbanded

The WAC as a branch was disbanded in 1978 and all female units were integrated with male units. Women serving as WACs at that time converted in branch to whichever Military Occupational Specialty they worked in. Since then, women in the US Army have served in the same units as men, though they have only been allowed in or near combat situations since 1994 when Defense Secretary Les Aspin ordered the removal of "substantial risk of capture" from the list of grounds for excluding women from certain military units. In 2015 Jeanne Pace, at the time the longest-tenured female warrant officer and the last former member of the WAC on active duty, retired.[42][43][44] She had joined the WAC in 1972.[43]

WAAC ranks

Originally there were only four enlisted (or "enrolled") WAAC ranks (auxiliary, junior leader, leader, and senior leader) and three WAC officer ranks (first, second and third officer). The Director was initially considered as equivalent to a major, then later made the equivalent of a colonel. The enlisted ranks expanded as the organization grew in size. Promotion was initially rapid and based on ability and skill. As members of a volunteer auxiliary group, the WAACs got paid less than their equivalent male counterparts in the US Army and did not receive any benefits or privileges.

WAAC organizational insignia was a Rising Eagle (nicknamed the "Waddling Duck" or "Walking Buzzard" by WAACs). It was worn in gold metal as cap badges and uniform buttons. Enlisted and NCO personnel wore it as an embossed circular cap badge on their Hobby Hats, while officers wore a "free" version (open work without a backing) on their hats to distinguish them. Their auxiliary insignia was the dark blue letters "WAAC" on an Olive Drab rectangle worn on the upper sleeve (below the stripes for enlisted ranks). WAAC personnel were not allowed to wear the same rank insignia as Army personnel. They were usually authorized to do so by post or unit commanders to help in indicating their seniority within the WAAC, although they had no authority over Army personnel.

| WAAC ranks (May, 1942 – April, 1943) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolled WAAC | US Army equivalent | WAAC officer | US Army equivalent | |||

| Senior leader | Master sergeant | Director of the WAAC | Major | |||

| Senior leader | First sergeant | First officer | Captain | |||

| Leader | Technical sergeant | Second officer | 1st lieutenant | |||

| Leader | Staff sergeant | Third officer | 2nd lieutenant | |||

| Leader | Sergeant | |||||

| Junior leader | Corporal | |||||

| Auxiliary first class | Private first class | |||||

| Auxiliary second class | Private | |||||

| Auxiliary third class | Recruit | |||||

| WAAC ranks (April, 1943 – July, 1943) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enlisted WAAC | US Army equivalent | WAAC officer | US Army equivalent | |||

| Chief leader | Master sergeant | Director of the WAAC | Colonel | |||

| First leader | First sergeant | Assistant Director of the WAAC | Lieutenant-colonel | |||

| Technical leader | Technical sergeant | Field director | Major | |||

| Staff leader | Staff sergeant | First officer | Captain | |||

| Leader | Sergeant | Second officer | 1st lieutenant | |||

| Junior leader | Corporal | Third officer | 2nd lieutenant | |||

| Auxiliary first class | Private first class | |||||

| Auxiliary second class | Private | |||||

| Auxiliary third class | Recruit | |||||

WAC ranks

The organization was renamed the Women's Army Corps in July 1943[45] when it was authorized as a branch of the US Army rather than an auxiliary group. The US Army's "GI Eagle" now replaced the WAAC's Rising Eagle as the WAC's cap badge. The WAC received the same rank insignia and pay as men later that September and received the same pay allowances and deductions as men in late October.[46] They were also the first women officers in the army allowed to wear officer's insignia; the Army Nursing Corps did not receive permission to do so until 1944.

The WAC had its own branch insignia (the Bust of Pallas Athena), worn by "Branch Immaterial" personnel (those unassigned to a Branch of Service). US Army policy decreed that technical and professional WAC personnel should wear their assigned Branch of Service insignia to reduce confusion. During the existence of the WAC (1943 to 1978) women were prohibited from being assigned to the combat arms branches of the Army – such as the Infantry, Cavalry, Armor, Tank Destroyers, or Artillery and could not serve in a combat area. However, they did serve as valuable staff in their headquarters and staff units stateside or in England.

The army's technician grades were technical and professional specialists similar to the later specialist grade. Technicians had the same insignia as NCOs of the same grade but had a "T" insignia (for "technician") beneath the chevrons. They were considered the same grade for pay but were considered a half-step between the equivalent pay grade and the next lower regular pay grade in seniority, rather than sandwiched between the junior enlisted (i.e., private – private first class) and the lowest NCO grade of rank (viz., corporal), as the modern-day specialist (E-4) is today. Technician grades were usually mistaken for their superior NCO counterparts due to the similarity of their insignia, creating confusion.

There were originally no warrant officers in the WAC in July, 1943. Warrant officer appointments for army servicewomen were authorized in January 1944. In March 1944 six WACs were made the first WAC Warrant Officers – as administrative specialists or band leaders. The number grew to 10 by June, 1944 and to 44 by June, 1945. By the time the war officially ended in September 1945, there were 42 WAC warrant officers still in Army service. There was only a trickle of appointments in the late 1940s after the war.

Most WAC officers were company-grade officers (lieutenants and captains), as the WAC were deployed as separate or attached detachments and companies. The field grade officers (majors and lieutenant-colonels) were on the staff under the director of the WAC, its solitary colonel.[47] Officers were paid by pay band rather than by grade or rank and did not receive a pay grade until 1955.

| WAC ranks (September, 1943 – 1945) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pay Grade | Enlisted WAC | Monthly pay | Yearly pay | WAC officers | Monthly pay | Yearly pay |

| Grade 1 | Master sergeant | $138 | $1656 | Colonel | $333 | $4000 |

| Grade 1 | First sergeant | $138 | $1656 | Lieutenant colonel | $291 | $3500 |

| Grade 2 | Technical sergeant | $114 | $1368 | Major | $250 | $3000 |

| Grade 3 | Staff sergeant | $96 | $1152 | Captain | $200 | $2400 |

| Grade 3 | Technician 3rd grade | $96 | $1152 | 1st lieutenant | $166 | $2000 |

| Grade 4 | Sergeant | $78 | $936 | 2nd lieutenant | $150 | $1800 |

| Grade 4 | Technician 4th grade | $78 | $936 | Chief warrant officer | $175 | $2100 |

| Grade 5 | Corporal | $66 | $792 | Warrant officer (junior grade) | $150 | $1800 |

| Grade 5 | Technician 5th grade | $66 | $792 | |||

| Grade 6 | Private first class | $54 | $648 | |||

| Grade 7 | Private | $50 | $600 | |||

- There were no chief warrant officer appointments in the WAC during the war because they did not meet the skill or seniority requirements for the rank. However, few servicemen did either. It required ten or more years of time in grade as either a warrant officer (junior grade) – a rank first created in 1941, staff warrant officer – a rank waitlisted since 1936, or an Army Mine Planter Service warrant officer – an Army sea auxiliary unit that was not allowed to recruit women.

List of directors

| • | Colonel Oveta Culp Hobby | (1942–1945) | |

| • | Colonel Westray Battle Boyce | (1945–1947) | |

| • | Colonel Mary A. Hallaren | (1947–1953) | |

| • | Colonel Irene O. Galloway | (1953–1957) | |

| • | Colonel Mary Louise Rasmuson | (1957–1962) | |

| • | Colonel Emily C. Gorman | (1962–1966) | |

| • | Brigadier General Elizabeth P. Hoisington | (1966–1971) | |

| • | Brigadier General Mildred Inez Caroon Bailey | (1971–1975) | |

| • | Brigadier General Mary E. Clarke | (1975–1978) |

Women's Army Corps Veterans' Association

The Women's Army Corps Veterans' Association—Army Women's United (WACVA) was organized in August 1947. Women who have served honorably in the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) or the Women's Army Corps (WAC) and those who have served or are serving honorably in the United States Army, the United States Army Reserve, or the Army National Guard of the United States, are eligible to be members. The association is a nonprofit, non-partisan organization representing women who "served their country in World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Grenada, Panama, Persian Gulf Bosnia and in Iraq and Afghanistan." WACVA sponsors an annual national convention and projects honoring women veterans. Local chapters of WACVA focus on volunteer work in Veterans Administration Hospitals and Community Service in the local and national community. The organization's newsletter THE CHANNEL "keeps the members aware of our national business, projects and pertinent veterans information."[48]

WACs

Colonel Geraldine Pratt May (b.1895 – d.1997 [served 1942-19??).[49] In March, 1943 May became one of the first female officers assigned to the Army Air Forces, serving as WAC Staff Director to the Air Transport Command. In 1948 she was promoted to Colonel (the first woman to hold that rank in the Air Force) and became Director of the WAF in the US Air Force, the first to hold the position.

Lt. Col. Charity Adams was the first commissioned African-American WAC and the second to be promoted to the rank of major. Promoted to major in 1945, she commanded the segregated all-female 6888th Central Postal Battalion in Birmingham, England. The 6888th landed with the follow-on troops during D-Day and were stationed in Rouen and then Paris during the invasion of France. It was the only African-American WAC unit to serve overseas during World War II.[50]

Lt. Col. Harriet West Waddy (b.1904-d.1999 [served 1942–1952])[51] was one of only two African-American women in the WAC to be promoted to the rank of major. Due to her earlier experience serving with director Mary McLeod Bethune of the Bureau of Negro Affairs, she became Colonel Culp's aide on race relations in the WAC. After the war, she was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel in 1948.

Lt. Col. Eleanore C. Sullivan [served 1952–1955] was WAC Center and WAC School commander located at Fort McClellan.[52]

Lieutenant Colonel Florence K. Murray served at WAC headquarters during World War II. She became the first female judge in Rhode Island in 1956. In 1977 she was the first woman to be elected as a justice of the Supreme Court of Rhode Island.

Major Elna Jane Hilliard [served 1942–1946] commanded the 2525th WAC unit at Fort Myer, Virginia. She was the first woman to serve on a United States Army general court martial.[53]

In January, 1943, Captain Frances Keegan Marquis became the first to command a women's expeditionary force,[54] the 149th WAAC Post Headquarters Company.[55] Serving in General Eisenhower's North African headquarters in Algiers, this group of about 200 women performed secretarial, driving, postal, and other non-combat duties.[56] An Army history called this company "one of the most highly qualified WAAC groups ever to reach the field. Hand-picked and all-volunteer, almost all members were linguists as well as qualified specialists, and almost all eligible for officer candidate school."[57]

Louisiana Register of State Lands Ellen Bryan Moore attained the rank of captain in the WACs and once recruited three hundred women at a single appeal to join the force.[58]

Captain Dovey Johnson Roundtree was among 39 African-American women recruited by Dr. Mary Bethune for the first WAACs officer training class. Roundtree was responsible for recruiting African-American women.[59] After leaving the Army, she went to Howard University law school and became a prominent civil rights lawyer in Washington, D.C. She was also one of the first women ordained in the A.M.E. Church.[60]

In February, 1943 Lieutenant Anna Mac Clarke became, when a Third Officer, the first African-American to lead an all-white WAAC unit.[61]

Sgt. Vashti R. Rutledge performed administrative work at the Army-Navy Staff College in Washington, DC. In March, 1944 WO(JG) Rutledge was one of the first six WACs to be granted a Warrant Officer's warrant.

Chief Warrant Officer 4 Elizabeth C. Smith USAF (WAC / USAAF 1944–1947, WAF / USAF 1948–1964) was one of the first WAF warrant officers in 1948.

Chief Warrant Officer 5 Jeanne Y. Pace, was the longest-serving female in the army and the last active duty soldier who was a part of the WAC as of 2011. Her final assignment was Bandmaster of the 1st Cavalry Division where she retired after 41 years of service.[62] She is also a recipient of the Daughters of the American Revolution Margaret Cochran Corbin Award which was established to pay tribute to women in all branches of the military for their extraordinary service[63] with previous recipients including Major Tammy Duckworth, Major General Gale Pollock, and Lt General Patricia Horoho.

Elizabeth "Tex" Williams was a military photographer.[64] She was one of the few women photographers that photographed all aspects of the military.[65]

Mattie Pinnette served as personal secretary to President Dwight D. Eisenhower.[66]

Popular culture

- During the war years, popular comic strip Dick Tracy, drawn by Chester Gould, featured a young WAC spurning the romantic advances of a villain. Likewise Tracy's sweetheart Tess Truehart was a WAC Corporal who helped Tracy capture the German Spy Alfred "The Brow" Brau in 1943.

- A series of cartoon postcards distributed during the war years depicted WACS hitting Adolf Hitler over the head with a rolling pin ["We're Giving Him A Big WAC!"], standing in morning formation exercises ["Don't Worry—Uncle Sam Is Keeping Us in Line!"], and window-shopping for civilian-style dresses ["Just Looking..."]

- The 1945 film Keep Your Powder Dry features Lana Turner joining the WACs, which starred Agnes Moorehead, while sporting uniforms designed by Hollywood designer Irene and hair styled by Sydney Guilaroff.

- The 1949 film I Was a Male War Bride depicts Cary Grant as a French officer who married an American WAC, played by Ann Sheridan and their escapades as he attempts to emigrate to the United States under the auspices of the 1945 War Brides Act.

- 1952 film Never Wave at a WAC stars Rosalind Russell, who plays the daughter of a senator, and joins to be closer to her boyfriend in Paris, but her ex-husband causes problems, but she falls back in love with him.

- The 1954 film Francis Joins the WACS stars Francis the Talking Mule, who joins the Women's Army Corps.

- General Blankenship's secretary, Corporal Etta Candy (Beatrice Colen) in the first season of Wonder Woman was a WAC veteran.

- The song Surrender by Cheap Trick is about a babyboomer child of a former member of the WAC who served in the Philippines.

- Mare's War, a novel by Tanita S. Davis, centers around an African-American girl who joins the WAC.

- On an episode of The Looney Tunes Show, Granny tells Daffy Duck a story where she served as a WAC and prevented the theft of the Eiffel Tower and numerous artworks from The Louvre.

- Miss Grundy, a teacher in the Archie Comics series, was a WAC.

- The Phil Silvers Show makes numerous references to the WACs. Several of the supporting cast, such as Sgt. Joan Hogan (Elisabeth Fraser), are members of the WAC and many of the gags and jokes in the show revolve around women in the army.

See also

- 32nd and 33rd Post Headquarters Companies

- 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion

- Air Transport Auxiliary

- Army Women's Museum

- Women in the Air Force (WAF)

- Women in the military

- Women in the United States Army

- Women's Army Volunteer Corp

Notes

- Moore, Brenda. (1996). To Serve My Country, to Serve My Race. New York: New York University Press.

- Treadwell 1954, pp. 28–30

- Meyer 1996, pp. 16–18

- Treadwell 1954, pp. 26–28

- Bellafaire 2003, pp. 2

- Bellafaire 2003, p. 2

- Bernard A. Cook, Women and war: a historical encyclopedia from antiquity to the present (2006) Volume 1 p. 242

- Bellafaire 2003, pp. 1

- Treadwell 1954, ch 3–4

- W. A. C. Field Manual Physical Training (FM 35-20). War Department, 15 July 1943. United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

- Bellafaire 1972, p. 2

- Video: American Army Women Serving On All Fronts Etc. (1944). Universal Newsreel. 1944. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- Treadwell 1954, pp. 387–388

- Leisa D. Meyer (1998). Creating G. I. Jane: Sexuality and Power in the Women's Army Corps During World War II. Columbia University Press. pp. 33–51. ISBN 9780231101455.

- Treadwell 1954, pp. 212–14

- Treadwell 1954

- Treadwell 1954, p. 184

- Ann Pfau, Miss Yourlovin: GIs, Gender, and Domesticity during World War II (Columbia University Press, 2008), chap. 2, online

- Treadwell 1954, pp. 194–201, 206–13

- "Editorial: The WAACs Are All Right". News-Press. Fort Myers, Florida. 16 June 1943. p. 4. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "WAC Gossip Lie, Says Stimson". Daily News. New York. Associated Press. 11 June 1943. p. 5. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- Ann Pfau, Miss Yourlovin: GIs, Gender, and Domesticity during World War II (Columbia University Press, 2008), chap. 2, online "Forced to retract his allegations, O'Donnell and his publisher remained determined to discredit the corps. Soon after this incident, O'Donnell was discovered 'canvassing Army general hospitals.' He sought [to] ascertain the number of Waacs hospitalized for pregnancy and thus defend his reputation with undeniable proof of promiscuity." Footnote omitted.

- Treadwell 1954, pp. 201–03

- O'Donnell, John (10 June 1943). "Capitol Stuff". Daily News. New York. p. 4. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

Colonel Oveta Culp Hobby, director of the WAACs, declared today that there is 'no foundation of truth' for the report that contraceptives and prophylactics will be furnished to the women in her organization. Col. Hobby's statement was made to refute the report which this column printed yesterday.

- Bellafaire 1972

- O'Donnell, John (9 June 1943). "Capitol Stuff". Daily News. New York. pp. 4, 356. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- O'Donnell, John (9 June 1943). "Capitol Stuff". The Times. Shreveport, Louisiana. p. 4. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Pyle, Ernie (8 July 1943). "Ernie Pyle About WACs: Mothers Needn't Worry—Girls Safe, Doing Big Job". The Boston Globe. p. 24. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Lardner, John (9 June 1943). "Lardner: WAACs Good Soldiers: Writer Resents Jokes That Have Been Written About Them and Refutes Slanderous Rumors—Praises Service in Africa". Indianapolis Star. p. 19. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

Lately another variety of buckshot has been aimed at the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps which is fast becoming the clay pigeon of the armed forces. The new story is ludicrous as well as unsanitary, but a lot of otherwise level-headed typewriter flailers have taken cognizance of it, so I guess it requires a little more counter-testimony from one who has seen and known the WAACs in North Africa.

- "Morals Are Good: Probe of WAACs Finds No Truth in Charges". Tipton Daily Tribune. Indiana. 6 July 1943. p. 3. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Treadwell 1954, pp. 216–18

- Treadwell 1954, pp. 205 Footnote omitted.

- Sandra Bolzenius, "Asserting Citizenship: Black Women in the Women’s Army Corps (wac)," International Journal of Military History and Historiography 39#2 (2019) : 208–231.

- Moore, Brenda L. (1997). To Serve My Country, to Serve My Race. NYU Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780814755877.

- Morden, Bettie J. (1992). The Women's Army Corps, 1945–1978. p. 34. ISBN 9781105093562.

- Treadwell 1954, p. 460

- Treadwell 1954, pp. 95–96

- Treadwell 1954, p. 408

- Campbell, p. 45

- Campbell, p. 49

- Treadwell 1954, pp. 326–29

- "Women's Army Corps veteran values support systems – The Redstone Rocket: News". The Redstone Rocket. 9 September 1971. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- "Longest-serving female warrant to retire after 43 years". Armytimes.com. 9 July 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- "Trooper reflects on 43 years of selfless service – Fort Hood Herald: Across The Fort". Kdhnews.com. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- Public Law 78-110 (signed into law on 3 July 1943)

- Servicemen's Allowance Act of 1942, amendment of 25 October 1943.

- Mrs. Hobby received the commissioned rank of colonel in the US Army on 5 July 1943

- "Women's Army Corps Veterans' Association – Army Women United". armywomen.org. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "Geraldine Pratt May". defense.gov. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- History, U.S. Army Center of Military. "6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion | Center of Military History". www.history.army.mil. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- "Military and Veteran Benefits, News, Veteran Jobs". military.com. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Morden, Bettie J., 1921– (1992). The women's army corps, 1945–1978. Center of Military History, U.S. Army. OCLC 42728896.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Education & Resources – National Women's History Museum – NWHM". nwhm.org. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Cowan, Ruth (1 February 1943). "Waac Skipper in North Africa Can Make A Very Nice Lemon Pie". The Palm Beach Post. Associated Press. p. 6. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- Treadwell 1954, p. 360

- "150 Hear Capt. Marquis Tell of Overseas Service". The Rutland Daily Herald. 14 February 1944. p. 12. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- Treadwell 1954, p. 360

- "Interview with Ellen Bryan Moore". T. Harry Williams Center for Oral History, Louisiana State University at Baton Rouge, Louisiana. September–October 1995. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010.

- "#VeteranOfTheDay Army Veteran Dovey Johnson Roundtree". Vantage Point: Official Blog of the U.S. Department of Veteran's Affairs. U.S. Department of Veteran's Affairs. 5 October 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- Fox, Margalit (21 May 2018). "Dovey Johnson Roundtree, Barrier-Breaking Lawyer, Dies at 104". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- Trowbridge, John M. "Anna Mac Clarke, World War II and the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps". Lest We Forget: African American Military History by Historian, Author, and Veteran Bennie McCrae, Jr. Hampton University. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- "[served 1972–2013". army.mil. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "Band commander receives award". army.mil. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- 1969–, Ellis, Jacqueline (1998). Silent witnesses : representations of working-class women in the United States. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. ISBN 9780879727444. OCLC 36589970.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- The reader's companion to U.S. women's history. Mankiller, Wilma Pearl, 1945–2010. Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin Co. 1998. ISBN 9780395671733. OCLC 47009823.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Kenneth S. Davis. Soldier of Democracy: A Biography of Dwight D. Eisenhower. New York, Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc. 1945. p. 467

References

- Bellafaire, Judith A. (1972). The Women's Army Corps: A Commemoration of World War II Service. Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Publication 72-15.

- Bolzenius, Sandra. "Asserting Citizenship: Black Women in the Women’s Army Corps (wac)," International Journal of Military History and Historiography 39#2 (2019) pp: 208–231.

- Campbell, D'Ann (1986). Women at War with America: Private Lives in a Patriotic Era. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-95475-0.

- Craven, Wesley Frank, and Cate, James Lea, editors. (1958). The Army Air Forces in World War II, Volume Seven - Services Around the World (PDF). Air Force Historical Studies Office.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Holm, Jeanne (1994). Women in the Military: An Unfinished Revolution. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-450-9., popular history

- Meyer, Leisa D. (1992). Creating GI Jane: Sexuality and Power in the Women's Army Corps During World War II. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10145-7.

- Morden, Bettie J. (2000). The Women's Army Corps, 1945–1978. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 30-14., scholarly history of postwar era

- Permeswaran, Yashila. "The Women's Army Auxiliary Corps: A Compromise to Overcome the Conflict of Women Serving in the Army." The History Teacher 42#1 (2008), pp. 95–111. online

- Putney, Martha S. (1992). When the Nation Was in Need: Blacks in the Women's Army Corps During World War II. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4017-0.

- Treadwell, Mattie E. (1954). The Women's Army Corps. United States Army in World War II (1991 ed.). United States Army Center of Military History. – full text; the standard scholarly history

Primary sources

- Green, Anne Bosanko. One Woman's War: Letters Home from the Women's Army Corps, 1944–1946 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1989)

- Samford, Doris E (1966). Ruffles and Drums. Pruett Press, Boulder, Colorado. ASIN B0006BP2XS.

- Earley, Charity Adams (1989). One Woman's Army: A Black Officer Remembers the WAC. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 0-89096-694-X.

- Moore, Brenda L. (1996). To Serve My Country, to Serve My Race: The Story of the Only African-American WACs Stationed Overseas during World War II. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-5587-9.

- Starbird, Ethel A. (2010). When Women First Wore Army Shoes: A first-person account of service as a member of the Women's Army Corps during WWII. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4502-0893-2.

Further reading

- Campbell, D'Ann. "Servicewomen of World War II." Armed Forces & Society 16.2 (1990): 251–270, based on interviews.

- Moore, Brenda L. (2004). Serving Our Country: Japanese American Women in the Military During World War II. Piscataway: Rutgers University Press. OCLC 760733468.

- Moore, Brenda L. (1996). To serve my country, to serve my race : the story of the only African American WACS stationed overseas during World War II. New York: New York University Press. OCLC 32854455.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Women's Army Corps. |

- Official website

- Women in Army History at the United States Army Center of Military History

- The Women's Army Corp History Brochure

- WAAC/WAC history and WWII women's uniforms in color – World War II US women's service organizations (WAC, WAVES, ANC, NNC, USMCWR, PHS, SPARS, ARC and WASP)

- Women Veterans Historical Collection – digitized letters, diaries, photographs, uniforms, and oral histories from WACs

- Papers of Fran Smith Johnson, WAC, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- The Slander Campaign book chapter by Ann Elizabeth Pfau

- WWII: Women in the Fight – slideshow by Life

- World War II uniform, Women’s Army Air Force, in the Staten Island Historical Society Online Collections Database

- Oral history interview with Gladys Donovan, a WAC from 1943–1946 from the Veterans History Project at Central Connecticut State University

- The WAC: The Story of the WAC in the ETO

- The short film Big Picture: The WAC is a Soldier, Too is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film It's Your War Too (1944) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- A film clip ALLIES TAKE KISKA ETC. (1943) is available at the Internet Archive

- Uniforms at A History of Central Florida Podcast

- Women's Army Corps Veterans' Association—Army Women United, Women's Army Corps Veterans' Association-Army Women United (WACVA-AWU)