Cary Grant

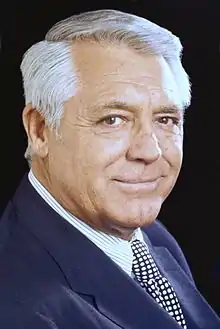

Cary Grant (born Archibald Alec Leach;[lower-alpha 1] January 18, 1904 – November 29, 1986) was an English-American actor, who was one of classic Hollywood's definitive leading men. He was known for his transatlantic accent, debonair demeanor, light-hearted approach to acting, and sense of comic timing.

Cary Grant | |

|---|---|

_01_Crisco_edit.jpg.webp) Cary Grant in 1941 | |

| Born | Archibald Alec Leach January 18, 1904 Bristol, England |

| Died | November 29, 1986 (aged 82) Davenport, Iowa, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Partner(s) | Maureen Donaldson (1973–1977)[1] |

| Children | Jennifer Grant (born 1966)[2] |

| Awards |

|

Grant was born in Horfield, Bristol, England. He became attracted to theater at a young age when he visited the Bristol Hippodrome.[6] At the age of 16, he went as a stage performer with the Pender Troupe for a tour of the US. After a series of successful performances in New York City, he decided to stay there.[7] He established a name for himself in vaudeville in the 1920s and toured the United States before moving to Hollywood in the early 1930s.

Grant initially appeared in crime films or dramas such as Blonde Venus (1932) with Marlene Dietrich and She Done Him Wrong (1933) with Mae West, but later gained renown for his performances in romantic and screwball comedies such as The Awful Truth (1937) with Irene Dunne, Bringing Up Baby (1938) with Katharine Hepburn, His Girl Friday (1940) with Rosalind Russell, and The Philadelphia Story (1940) with Hepburn and James Stewart. These pictures are frequently cited among the greatest comedy films of all time.[8] Other well-known films in which he starred in this period were the adventure Gunga Din (1939) and the dark comedy Arsenic and Old Lace (1944). He also began to move into dramas such as Only Angels Have Wings (1939), Penny Serenade (1941) and Clifford Odets's None but the Lonely Heart (1944); he was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor for the latter two.

During the 1940s and 1950s, Grant developed a close working relationship with director Alfred Hitchcock, who cast him in the critically acclaimed films Suspicion (1941), Notorious (1946) and North by Northwest (1959), plus the popular To Catch a Thief (1955). The suspense-dramas Suspicion and Notorious, the latter his first pairing with Ingrid Bergman, both involved Grant showing a darker, more ambiguous nature in his characters. Toward the end of his career, Grant was praised by critics as a romantic leading man, and he received five nominations for the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor, including Indiscreet (1958) with Ingrid Bergman, That Touch of Mink (1962) with Doris Day, and Charade (1963) with Audrey Hepburn. He is remembered by critics for his unusually broad appeal as a handsome, suave actor who did not take himself too seriously, able to play with his own dignity in comedies without sacrificing it entirely.

Grant was married five times, three of them elopements with actresses: Virginia Cherrill (1934–1935), Betsy Drake (1949–1962), and Dyan Cannon (1965–1968). He retired from film acting in 1966 and pursued numerous business interests, representing cosmetics firm Fabergé and sitting on the board of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. In 1970, he was presented with an Honorary Oscar by his friend Frank Sinatra at the 42nd Academy Awards, and he was accorded the Kennedy Center Honors in 1981. He died five years later from a stroke in Davenport, Iowa. In 1999, the American Film Institute named him the second greatest male star of Golden Age Hollywood cinema, trailing only Humphrey Bogart.

Early life and education

Grant was born Archibald Alec Leach on January 18, 1904, at 15 Hughenden Road in the northern Bristol suburb of Horfield.[9][4] He was the second child of Elias James Leach (1872–1935) and Elsie Maria Leach (née Kingdon; 1877–1973).[10] His father worked as a tailor's presser at a clothes factory, while his mother worked as a seamstress.[11] His older brother John (1895 or 1899 (sources differ)[12] –1900) died of tuberculous meningitis.[13] Grant may have considered himself partly Jewish.[lower-alpha 2] He had an unhappy upbringing; his father was an alcoholic[18] and his mother suffered from clinical depression.[19]

—Grant's wife Dyan Cannon on his childhood.[20]

Grant's mother taught him song and dance when he was four, and she was keen on him having piano lessons.[21] She occasionally took him to the cinema, where he enjoyed the performances of Charlie Chaplin, Chester Conklin, Fatty Arbuckle, Ford Sterling, Mack Swain, and Broncho Billy Anderson.[22] He was sent to the Bishop Road Primary School, Bristol when he was 4½.[23]

Grant's biographer Graham McCann claimed that his mother "did not know how to give affection and did not know how to receive it either".[24] Biographer Geoffrey Wansell notes that his mother blamed herself bitterly for the death of Grant's brother John, and never recovered from it.[lower-alpha 3] Grant acknowledged that his negative experiences with his mother affected his relationships with women later in life.[25] She frowned on alcohol and tobacco,[10] and would reduce pocket money for minor mishaps.[26] Grant attributed her behavior to overprotectiveness, fearing that she would lose him as she did John.[21]

When Grant was nine years old, his father placed his mother in Glenside Hospital, a mental institution, and told him that she had gone away on a "long holiday";[27] he later declared that she had died.[18] Grant grew up resenting his mother, particularly after she left the family. After she was gone, Grant and his father moved into his grandmother's home in Bristol.[28] When Grant was 10, his father remarried and started a new family,[20] and Grant did not learn that his mother was still alive until he was 31;[29] his father confessed to the lie shortly before his own death.[20] Grant made arrangements for his mother to leave the institution in June 1935, shortly after he learned of her whereabouts.[30] He visited her in October 1938 after filming was completed for Gunga Din.[31]

Grant enjoyed the theater, particularly pantomimes at Christmas, which he attended with his father.[26] He befriended a troupe of acrobatic dancers known as "The Penders" or the "Bob Pender Stage Troupe".[32] He subsequently trained as a stilt walker and began touring with them.[33] Jesse Lasky was a Broadway producer at the time and saw Grant performing at the Wintergarten theater in Berlin around 1914.[34]

In 1915, Grant won a scholarship to attend Fairfield Grammar School in Bristol, although his father could barely afford to pay for the uniform.[35] He was quite capable in most academic subjects,[lower-alpha 4] but he excelled at sports, particularly fives, and his good looks and acrobatic talents made him a popular figure.[37][38] He developed a reputation for mischief, and frequently refused to do his homework.[39] A former classmate referred to him as a "scruffy little boy", while an old teacher remembered "the naughty little boy who was always making a noise in the back row and would never do his homework".[37] He spent his evenings working backstage in Bristol theaters, and was responsible for the lighting for magician David Devant at the Bristol Empire in 1917 at the age of 13.[40] He began hanging around backstage at the theater at every opportunity,[36] and volunteered for work in the summer as a messenger boy and guide at the military docks in Southampton, to escape the unhappiness of his home life.[41] The time spent at Southampton strengthened his desire to travel; he was eager to leave Bristol and tried to sign on as a ship's cabin boy, but he was too young.[42]

On March 13, 1918,[43] Grant was expelled from Fairfield.[44] Several explanations were given, including being discovered in the girls' lavatory[45] and assisting two other classmates with theft in the nearby town of Almondsbury.[46] Wansell claims that Grant had set out intentionally to get himself expelled from school to pursue a career in entertainment with the troupe,[47] and he did rejoin Pender's troupe three days after being expelled. His father had a better-paying job in Southampton, and Grant's expulsion brought local authorities to his door with questions about why his son was living in Bristol and not with his father in Southampton. His father then co-signed a three-year contract between Grant and Pender that stipulated Grant's weekly salary, along with room and board, dancing lessons, and other training for his profession until age 18. There was also a provision in the contract for salary raises based on job performance.[48]

Vaudeville and performing career

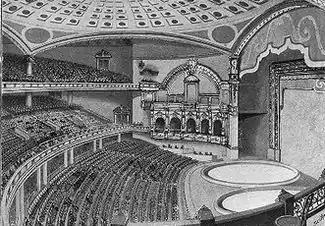

The Pender Troupe began touring the country, and Grant developed the ability in pantomime to broaden his physical acting skills.[47] They traveled on the RMS Olympic to conduct a tour of the United States on July 21, 1920 when he was 16, arriving a week later.[7] Biographer Richard Schickel writes that Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford were aboard the same ship, returning from their honeymoon, and that Grant played shuffleboard with him. He was so impressed with Fairbanks that he became an important role model.[49] After arriving in New York, the group performed at the New York Hippodrome, which was the largest theater in the world at the time with a capacity of 5,697. They performed there for nine months, putting on 12 shows a week, and they had a successful production of Good Times.[50]

—Grant on stand-up comedy.[51]

Grant became a part of the vaudeville circuit and began touring, performing in places such as St. Louis, Missouri, Cleveland, and Milwaukee,[52] and he decided to stay in the US with several of the other members when the rest of the troupe returned to Britain.[53] He became fond of the Marx Brothers during this period, and Zeppo Marx was an early role model for him.[54] In July 1922, he performed in a group called the "Knockabout Comedians" at the Palace Theater on Broadway.[52] He formed another group that summer called "The Walking Stanleys" with several of the former members of the Pender Troupe, and he starred in a variety show named "Better Times" at the Hippodrome towards the end of the year.[55] He met George C. Tilyou at a party, the owner of the Steeplechase Park racecourse on Coney Island.[52] Tilyou hired him to appear there on stilts and attract large crowds, wearing a bright-great coat and a sandwich board which advertised the race-track.[54]

Grant spent the next couple of years touring the United States with "The Walking Stanleys". He visited Los Angeles for the first time in 1924, which made a lasting impression on him.[52] The group split up and he returned to New York, where he began performing at the National Vaudeville Artists Club on West 46th Street, juggling, performing acrobatics and comic sketches, and having a short spell as a unicycle rider known as "Rubber Legs".[56] The experience was a particularly demanding one, but it gave Grant the opportunity to improve his comic technique and to develop skills which benefitted him later in Hollywood.[57]

Grant became a leading man alongside Jean Dalrymple and decided to form the "Jack Janis Company", which began touring vaudeville.[58] He was sometimes mistaken for an Australian during this period and was nicknamed "Kangaroo" or "Boomerang".[59] His accent seemed to have changed as a result of moving to London with the Pender troupe and working in many music halls in the UK and the US, and eventually became what some term a transatlantic or mid-Atlantic accent.[60][lower-alpha 5] In 1927, he was cast as an Australian in Reggie Hammerstein's musical Golden Dawn, for which he earned $75 a week.[63] The show was not well received, but it lasted for 184 performances and several critics started to notice Grant as the "pleasant new juvenile" or "competent young newcomer".[63] The following year, he joined the William Morris Agency and was offered another juvenile part by Hammerstein in his play Polly, an unsuccessful production.[64] One critic wrote that Grant "has a strong masculine manner, but unfortunately fails to bring out the beauty of the score."[51] Wansell notes that the pressure of a failing production began to make him fret, and he was eventually dropped from the run after six weeks of poor reviews.[65] Despite the setback, Hammerstein's rival Florenz Ziegfeld made an attempt to buy Grant's contract, but Hammerstein sold it to the Shubert Brothers instead.[65] J. J. Shubert cast him in a small role as a Spaniard opposite Jeanette MacDonald in the French risqué comedy Boom-Boom at the Casino Theater on Broadway, which premiered on January 28, 1929.[66] MacDonald later admitted that Grant was "absolutely terrible in the role", but he exhibited a charm which endeared him to people and effectively saved the show from failure.[65] The play ran for 72 shows, and Grant earned $350 a week before moving to Detroit, then to Chicago.[67][lower-alpha 6]

To console himself, Grant bought a 1927 Packard sport phaeton.[65] He visited his half-brother Eric in England, and he returned to New York to play the role of Max Grunewald in a Shubert production of A Wonderful Night.[68] It premiered at the Majestic Theater on October 31, 1929, two days after the Wall Street Crash, and lasted until February 1930 with 125 shows.[69] The play received mixed reviews; one critic criticized his acting, likening it to a "mixture of John Barrymore and cockney", while another announced that he had brought a "breath of elfin Broadway" to the role.[70] Grant still found it difficult forming relationships with women, remarking that he "never seemed able to fully communicate with them" even after many years "surrounded by all sorts of attractive girls" in the theater, on the road, and in New York.[71]

In 1930, Grant toured for nine months in a production of the musical The Street Singer.[72] It ended in early 1931, and the Shuberts invited him to spend the summer performing on the stage at The Muny in St. Louis, Missouri; he appeared in 12 different productions, putting on 87 shows.[73][lower-alpha 7] He received praise from local newspapers for these performances, gaining a reputation as a romantic leading man.[72] Significant influences on his acting in this period were Gerald du Maurier, A. E. Matthews, Jack Buchanan, and Ronald Squire.[75] He admitted that he was drawn to acting because of a "great need to be liked and admired".[10] He was eventually fired by the Shuberts at the end of the summer season when he refused to accept a pay cut because of financial difficulties caused by the Depression.[71] His unemployment was short lived, however; impresario William B. Friedlander offered him the lead romantic part in his musical Nikki, and Grant starred opposite Fay Wray as a soldier in post-World War I France. The production opened on September 29, 1931 in New York, but was stopped after just 39 performances due to the effects of the Depression.[71]

Film career

Early roles (1932–1936)

Grant's role in Nikki was praised by Ed Sullivan of The New York Daily News, who noted that the "young lad from England" had "a big future in the movies".[76] The review led to another screen test by Paramount Publix, resulting in an appearance as a sailor in Singapore Sue (1931),[77] a ten-minute short film by Casey Robinson.[76] Grant delivered his lines "without any conviction" according to McCann.[lower-alpha 8] Through Robinson, Grant met with Jesse L. Lasky and B. P. Schulberg, the co-founder and general manager of Paramount Pictures respectively.[79] After a successful screen-test directed by Marion Gering,[lower-alpha 9] Schulberg signed a contract with the 27-year-old Grant on December 7, 1931 for five years,[80] at a starting salary of $450 a week.[81] Schulberg demanded that he change his name to "something that sounded more all-American like Gary Cooper", and they eventually agreed on Cary Grant.[82][lower-alpha 10]

Grant set out to establish himself as what McCann calls the "epitome of masculine glamour", and made Douglas Fairbanks his first role model.[84] McCann notes that Grant's career in Hollywood immediately took off because he exhibited a "genuine charm", which made him stand out among the other good looking actors at the time, making it "remarkably easy to find people who were willing to support his embryonic career".[85] He made his feature film debut with the Frank Tuttle-directed comedy This is the Night (1932), playing an Olympic javelin thrower opposite Thelma Todd and Lili Damita.[86] Grant disliked his role and threatened to leave Hollywood,[87] but to his surprise a critic from Variety praised his performance, and thought that he looked like a "potential femme rave".[88]

In 1932, Grant played a wealthy playboy opposite Marlene Dietrich in Blonde Venus, directed by Josef von Sternberg. Grant's role is described by William Rothman as projecting the "distinctive kind of nonmacho masculinity that was to enable him to incarnate a man capable of being a romantic hero".[89] Grant found that he conflicted with the director during the filming and the two often argued in German.[90] He played a suave playboy type in a number of films: Merrily We Go to Hell opposite Fredric March and Sylvia Sidney, Devil and the Deep alongside Gary Cooper, Charles Laughton and Tallulah Bankhead, Hot Saturday opposite Nancy Carroll and Randolph Scott,[91] and Madame Butterfly with Sidney.[92][93] According to biographer Marc Eliot, while these films did not make Grant a star, they did well enough to establish him as one of Hollywood's "new crop of fast-rising actors".[94]

In 1933, Grant gained attention for appearing in the pre-Code films She Done Him Wrong and I'm No Angel opposite Mae West.[lower-alpha 11] West would later claim that she had discovered Cary Grant.[97][lower-alpha 12] Pauline Kael noted that Grant did not appear confident in his role as a Salvation Army director in She Done Him Wrong, which made it all the more charming.[99][100] The film was a box office hit, earning more than $2 million in the United States,[101] and has since won much acclaim.[lower-alpha 13] For I'm No Angel, Grant's salary was increased from $450 to $750 a week.[104] The film was even more successful than She Done Him Wrong, and saved Paramount from bankruptcy;[104] Vermilye cites it as one of the best comedy films of the 1930s.[105]

After a string of financially unsuccessful films, which included roles as a president of a company who is sued for knocking down a boy in an accident in Born to Be Bad (1934) for 20th Century Fox,[lower-alpha 14] a cosmetic surgeon in Kiss and Make-Up (1934),[107] and a blinded pilot opposite Myrna Loy in Wings in the Dark (1935), and press reports of problems in his marriage to Cherrill,[lower-alpha 15] Paramount concluded that Grant was expendable.[108][lower-alpha 16]

Grant's prospects picked up in the latter half of 1935 when he was loaned to RKO Pictures.[111] Producer Pandro Berman agreed to take him on in the face of failure because "I'd seen him do things which were excellent, and [Katharine] Hepburn wanted him too."[112] His first venture with RKO, playing a raffish cockney swindler in George Cukor's Sylvia Scarlett (1935), was the first of four collaborations with Hepburn.[113][lower-alpha 17] Though a commercial failure,[115] his dominating performance was praised by critics,[116] and Grant always considered the film to have been the breakthrough for his career.[117] When his contract with Paramount ended in 1936 with the release of Wedding Present, Grant decided not to renew it and wished to work freelance. Grant claimed to be the first freelance actor in Hollywood and the lack of central contract helped increase his salary to $300,000 per picture.[118] His first venture as a freelance actor was The Amazing Quest of Ernest Bliss (1936), which was shot in England.[117] The film was a box office bomb and prompted Grant to reconsider his decision. Critical and commercial success with Suzy later that year in which he played a French airman opposite Jean Harlow and Franchot Tone, led to him signing joint contracts with RKO and Columbia Pictures, enabling him to choose the stories that he felt suited his acting style.[118] His Columbia contract was a four-film deal over two years, guaranteeing him $50,000 each for the first two and $75,000 each for the others.[119]

Hollywood stardom and Oscar recognition (1937–1944)

In 1937, Grant began the first film under his contract with Columbia Pictures, When You're in Love, portraying a wealthy American artist who eventually woos a famous opera singer (Grace Moore). His performance received positive feedback from critics, with Mae Tinee of The Chicago Daily Tribune describing it as the "best thing he's done in a long time".[120] After a commercial failure in his second RKO venture The Toast of New York,[121][122] Grant was loaned to Hal Roach's studio for Topper, a screwball comedy film distributed by MGM, which became his first major comedy success.[123] Grant played one half of a wealthy, freewheeling married couple with Constance Bennett,[124] who wreak havoc on the world as ghosts after dying in a car accident.[125] Topper became one of the most popular movies of the year, with a critic from Variety noting that both Grant and Bennett "do their assignments with great skill".[126] Vermilye described the film's success as "a logical springboard" for Grant to star in The Awful Truth that year,[127] his first film made with Irene Dunne and Ralph Bellamy. Though director Leo McCarey reportedly disliked Grant,[128] who had mocked the director by enacting his mannerisms in the film,[129] he recognized Grant's comic talents and encouraged him to improvise his lines and draw upon his skills developed in vaudeville.[128] The film was a critical and commercial success and made Grant a top Hollywood star,[130] establishing a screen persona for him as a sophisticated light comedy leading man in screwball comedies.[131]

The Awful Truth began what film critic Benjamin Schwarz of The Atlantic later called "the most spectacular run ever for an actor in American pictures" for Grant.[132] In 1938, he starred opposite Katharine Hepburn in the screwball comedy Bringing Up Baby, featuring a leopard and frequent bickering and verbal jousting between Grant and Hepburn.[133] He was initially uncertain how to play his character, but was told by director Howard Hawks to think of Harold Lloyd.[134] Grant was given more leeway in the comic scenes, the editing of the film and in educating Hepburn in the art of comedy.[135] Despite losing over $350,000 for RKO,[136] the film earned rave reviews from critics.[137] He again appeared with Hepburn in the romantic comedy Holiday later that year, which did not fare well commercially, to the point that Hepburn was considered to be "box office poison" at the time.[138]

Despite a series of commercial failures, Grant was now more popular than ever and in high demand.[139] According to Vermilye, in 1939, Grant played roles that were more dramatic, albeit with comical undertones.[140] He played a British army sergeant opposite Douglas Fairbanks Jr. in the George Stevens-directed adventure film Gunga Din, set at a military station in India.[141][lower-alpha 18] Roles as a pilot opposite Jean Arthur and Rita Hayworth in Hawks' Only Angels Have Wings,[143] and a wealthy landowner alongside Carole Lombard in In Name Only followed.[144]

In 1940, Grant played a callous newspaper editor who learns that his ex-wife and former journalist, played by Rosalind Russell, is to marry insurance officer Ralph Bellamy in Hawks' comedy His Girl Friday,[145] which was praised for its strong chemistry and "great verbal athleticism" between Grant and Russell.[146][147][lower-alpha 19] Grant reunited with Irene Dunne in My Favorite Wife, a "first rate comedy" according to Life magazine,[148] which became RKO's second biggest picture of the year, with profits of $505,000.[149][lower-alpha 20] After playing a Virginian backwoodsman in the American Revolution-set The Howards of Virginia, which McCann considers to have been Grant's worst film and performance,[151] his last film of the year was in the critically lauded romantic comedy The Philadelphia Story, in which he played the ex-husband of Hepburn's character.[152][153][154] Grant felt his performance was so strong that he was bitterly disappointed not to have received an Oscar nomination, especially since both his lead co-stars, Hepburn and James Stewart, received nominations, with Stewart winning for Best Actor.[155] Grant joked "I'd have to blacken my teeth first before the Academy will take me seriously".[155] Film historian David Thomson wrote that "the wrong man got the Oscar" for The Philadelphia Story and that "Grant got better performances out of Hepburn than her (long-time companion) Spencer Tracy ever managed."[156] Stewart's winning the Oscar "was considered a gold-plated apology for his being robbed of the award" for the previous year's Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.[157][158] Grant's not being nominated for His Girl Friday the same year is also a "sin of omission" for the Oscars.[157]

The following year Grant was considered for the Academy Award for Best Actor for Penny Serenade—his first nomination from the Academy. Wansell claims that Grant found the film to be an emotional experience, because he and wife-to-be Barbara Hutton had started to discuss having their own children.[159] Later that year he appeared in the romantic psychological thriller Suspicion, the first of Grant's four collaborations with director Alfred Hitchcock. Grant did not warm to co-star Joan Fontaine, finding her to be temperamental and unprofessional.[160] Film critic Bosley Crowther of The New York Times considered that Grant was "provokingly irresponsible, boyishly gay and also oddly mysterious, as the role properly demands".[161] Hitchcock later stated that he thought the ending of the film in which Grant is sent to jail instead of committing suicide "a complete mistake because of making that story with Cary Grant. Unless you have a cynical ending it makes the story too simple".[162] Geoff Andrew of Time Out believes Suspicion served as "a supreme example of Grant's ability to be simultaneously charming and sinister".[163]

In 1942, Grant participated in a three-week tour of the United States as part of a group to help the war effort and was photographed visiting wounded marines in hospital. He appeared in several routines of his own during these shows and often played the straight-man opposite Bert Lahr.[164] In May 1942, the ten-minute propaganda short Road to Victory was released, in which he appeared alongside Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra and Charles Ruggles.[165] On film, Grant played Leopold Dilg, a convict on the run in The Talk of the Town (1942), who escapes after being wrongly convicted of arson and murder. He hides in a house with characters played by Jean Arthur and Ronald Colman, and gradually plots to secure his freedom. Crowther praised the script, and noted that Grant played Dilg with a "casualness which is slightly disturbing".[166] After a role as a foreign correspondent opposite Ginger Rogers and Walter Slezak in the off-beat comedy Once Upon a Honeymoon,[167] in which he was praised for his scenes with Rogers,[168] he appeared in Mr. Lucky the following year, playing a gambler in a casino aboard a ship.[169] The commercially successful submarine war film Destination Tokyo (1943) was shot in just six weeks in the September and October, which left him exhausted;[170] the reviewer from Newsweek thought it was one of the finest performances of his career.[171]

In 1944, Grant starred alongside Priscilla Lane, Raymond Massey and Peter Lorre,[172] in Frank Capra's dark comedy Arsenic and Old Lace, playing the manic Mortimer Brewster, who belongs to a bizarre family which includes two murderous aunts and an uncle claiming to be President Teddy Roosevelt.[173] Grant took up the role after it was originally offered to Bob Hope, who turned it down owing to schedule conflicts.[174][175] Grant found the macabre subject matter of the film difficult to contend with and believed that it was the worst performance of his career.[176] That year he received his second Oscar nomination for a role, opposite Ethel Barrymore and Barry Fitzgerald in the Clifford Odets-directed film None but the Lonely Heart, set in London during the Depression.[177] Late in the year he featured in the CBS Radio series Suspense, playing a tormented character who hysterically discovers that his amnesia has affected masculine order in society in The Black Curtain.[178]

Post-War success and slump (1946–1954)

After making a brief cameo appearance opposite Claudette Colbert in Without Reservations (1946),[179] Grant portrayed Cole Porter in the musical Night and Day (1946).[180] The production proved to be problematic, with scenes often requiring multiple takes, frustrating the cast and crew.[180] Grant next appeared with Ingrid Bergman and Claude Rains in the Hitchcock-directed film Notorious (1946), playing a government agent who recruits the American daughter of a convicted Nazi spy (Bergman) to infiltrate a Nazi organization in Brazil after World War II.[181] During the course of the film Grant and Bergman's characters fall in love and share one of the longest kisses in film history at around two-and-a-half minutes.[182][183] Wansell notes how Grant's performance "underlined how far his unique qualities as a screen actor had matured in the years since The Awful Truth".[184]

In 1947, Grant played an artist who becomes involved in a court case when charged with assault in The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer (released in the U.K. as "Bachelor Knight"), opposite Myrna Loy and Shirley Temple.[185][186] The film was praised by the critics, who admired the picture's slapstick qualities and chemistry between Grant and Loy;[187] it became one of the biggest-selling films at the box office that year.[188] Later that year he starred opposite David Niven and Loretta Young in the comedy The Bishop's Wife, playing an angel who is sent down from heaven to straighten out the relationship between the bishop (Niven) and his wife (Loretta Young).[189] The film was a major commercial and critical success, and was nominated for five Academy Awards.[190] Life magazine called it "intelligently written and competently acted".[189] The following year, Grant played neurotic Jim Blandings, the title-sake in the comedy Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, again with Loy. Though the film lost money for RKO,[191] Philip T. Hartung of Commonweal thought that Grant's role as the "frustrated advertising man" was one of his best screen portrayals.[192] In Every Girl Should Be Married, an "airy comedy", he appeared with Betsy Drake and Franchot Tone, playing a bachelor who is trapped into marriage by Drake's conniving character.[193] He finished the year as the fourth most popular film star at the box office.[194]

In 1949, Grant starred alongside Ann Sheridan in the comedy I Was a Male War Bride in which he appeared in scenes dressed as a woman, wearing a skirt and a wig.[195] During the filming he was taken ill with infectious hepatitis and lost weight, affecting the way he looked in the picture.[196] The film proved to be successful, becoming the highest-grossing film for 20th Century Fox that year with over $4.5 million in takings and being likened to Hawks's screwball comedies of the late 1930s.[188] By this point he was one of the highest paid Hollywood stars, commanding $300,000 per picture.[197]

The early 1950s marked the beginning of a slump in Grant's career.[198][199] His roles as a top brain surgeon who is caught in the middle of a bitter revolution in a Latin American country in Crisis,[200] and as a medical-school professor and orchestra conductor opposite Jeanne Crain in People Will Talk were poorly received.[201][202] Grant had become tired of being Cary Grant after twenty years, being successful, wealthy and popular, and remarked: "To play yourself, your true self, is the hardest thing in the world".[203] In 1952, Grant starred in the comedy Room for One More, playing an engineer husband who with his wife (Betsy Drake) adopt two children from an orphanage.[204][205] He reunited with Howard Hawks to film the off-beat comedy Monkey Business, co-starring Ginger Rogers and Marilyn Monroe.[206] Though the critic from Motion Picture Herald wrote gushingly that Grant had given a career's best with an "extraordinary and agile performance", which was matched by Rogers,[207] it received a mixed reception overall.[lower-alpha 21] Grant had hoped that starring opposite Deborah Kerr in the romantic comedy Dream Wife would salvage his career,[198] but it was a critical and financial failure upon release in July 1953. Though he was considered for the leading part in A Star is Born, Grant believed that his film career was over, and briefly left the industry.[209]

Romantic leading man and final roles (1955–1966)

In 1955, Grant agreed to star opposite Grace Kelly in To Catch a Thief, playing a retired jewel thief nicknamed "The Cat", living in the French Riviera.[210] Grant and Kelly worked well together during the production, which was one of the most enjoyable experiences of Grant's career. He found Hitchcock and Kelly to be very professional,[211] and later stated that Kelly was "possibly the finest actress I've ever worked with".[212][lower-alpha 22] Grant was one of the first actors to go independent by not renewing his studio contract,[213] effectively leaving the studio system, which almost completely controlled all aspects of an actor's life.[214] He decided which films he was going to appear in, often had personal choice of directors and co-stars, and at times negotiated a share of the gross revenue, something uncommon at the time.[215] Grant received more than $700,000 for his 10% of the gross of the successful To Catch a Thief, while Hitchcock received less than $50,000 for directing and producing it.[216] Though critical reception to the overall film was mixed, Grant received high praise for his performance, with critics commenting on his suave, handsome appearance in the film.[215]

In 1957, Grant starred opposite Kerr in the romance An Affair to Remember, playing an international playboy who becomes the object of her affections. Schickel sees the film as one of the definitive romantic pictures of the period, but remarks that Grant was not entirely successful in trying to supersede the film's "gushing sentimentality".[217] That year, Grant also appeared opposite Sophia Loren in The Pride and the Passion. He had expressed an interest in playing William Holden's character in The Bridge on the River Kwai at the time, but found that it was not possible because of his commitment to The Pride and the Passion.[218] The film was shot on location in Spain and was problematic, with co-star Frank Sinatra irritating his colleagues and leaving the production after just a few weeks.[219] Although Grant had an affair with Loren during filming, Grant's attempts to woo Loren to marry him during the production proved fruitless,[lower-alpha 23] which led to him expressing anger when Paramount cast her opposite him in Houseboat (1958) as part of her contract.[221] The sexual tension between the two was so great during the making of Houseboat that the producers found it almost impossible to make.[220] Later in 1958, Grant starred opposite Bergman in the romantic comedy Indiscreet, playing a successful financier who has an affair with a famous actress (Bergman) while pretending to be a married man.[222] During the filming he formed a closer friendship and gained new respect for her as an actress.[223] Schickel stated that he thought the film was possibly the finest romantic comedy film of the era, and that Grant himself had professed that it was one of his personal favorites.[224] Grant received his first of five Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy nominations for his performance and finished the year as the most popular film star at the box office.[194]

In 1959, Grant starred in the Hitchcock-directed film North by Northwest, playing an advertising executive who becomes embroiled in a case of mistaken identity. Like Indiscreet,[225][226] it was warmly received by the critics and was a major commercial success,[227] and is now often listed as one of the greatest films of all time.[lower-alpha 24] Weiler, writing in The New York Times, praised Grant's performance, remarking that the actor "was never more at home than in this role of the advertising-man-on-the-lam" and handled the role "with professional aplomb and grace".[231] Grant wore one of his most iconic suits in the film which became very popular, a fourteen-gauge, mid-gray, worsted wool one custom-made on Savile Row.[232][233] Grant finished the year playing a U.S. Navy Rear Admiral aboard a submarine opposite Tony Curtis in the comedy Operation Petticoat.[234] The reviewer from Daily Variety saw Grant's comic portrayal as a classic example of how to attract the laughter of the audience without lines, remarking that "In this film, most of the gags play off him. It is his reaction, blank, startled, etc., always underplayed, that creates or releases the humor".[235] The film was major box office success, and in 1973, Deschner ranked the film as the highest earning film of Grant's career at the US box office, with takings of $9.5 million.[236]

In 1960, Grant appeared opposite Robert Mitchum, Jean Simmons and Deborah Kerr in The Grass Is Greener, which was shot in England at Osterley Park and Shepperton Studios.[237] McCann notes that Grant took great relish in "mocking his aristocratic character's over-refined tastes and mannerisms",[238] though the film was panned and was seen as his worst since Dream Wife.[239] In 1962, Grant starred in the romantic comedy That Touch of Mink, playing suave, wealthy businessman Philip Shayne romantically involved with an office worker, played by Doris Day. He invites her to his apartment in Bermuda, but her guilty conscience begins to take hold.[240] The picture was praised by critics, and it received three Academy Award nominations, and won the Golden Globe Award for Best Comedy Picture,[241] in addition to another Golden Globe Award nomination for Best Actor.[242] Deschner ranked the film as the second highest grossing of Grant's career.[236]

Producers Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman originally sought Grant for the role of James Bond in Dr. No (1962) but discarded the idea as Grant would be committed to only one feature film; therefore, the producers decided to go after someone who could be part of a franchise.[243] In 1963, Grant appeared in his last typically suave, romantic role opposite Audrey Hepburn in Charade.[244] Grant found the experience of working with Hepburn "wonderful" and believed that their close relationship was clear on camera,[245] though according to Hepburn, he was particularly worried during the filming that he would be criticized for being far too old for her and seen as a "cradle snatcher".[246] Author Chris Barsanti writes: "It's the film's canny flirtatiousness that makes it such ingenious entertainment. Grant and Hepburn play off each other like the pros that they are".[247] The film, well received by the critics,[248] is often called "the best Hitchcock film Hitchcock never made".[249][250][251]

In 1964, Grant changed from his typically suave, distinguished screen persona to play a grizzled beachcomber Walter Eckland who is hired by a Commander (Trevor Howard) to serve as a lookout on Matalava Island for invading Japanese planes in the World War II romantic comedy, Father Goose.[252] The film was a major commercial success, and upon its release at Radio City at Christmas 1964 it took over $210,000 at the box-office in the first week, breaking the record set by Charade the previous year.[253] Grant's final film, Walk, Don't Run (1966), a comedy co-starring Jim Hutton and Samantha Eggar, was shot on location in Tokyo,[254] and is set amid the backdrop of the housing shortage of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.[255] Newsweek concluded: "Though Grant's personal presence is indispensable, the character he plays is almost wholly superfluous. Perhaps the inference to be taken is that a man in his 50s or 60s has no place in romantic comedy except as a catalyst. If so, the chemistry is wrong for everyone".[256] Hitchcock had asked Grant to star in Torn Curtain that year only to learn that he had decided to retire.[257]

Later years

Grant retired from the screen at 62 when his daughter Jennifer Grant was born in order to focus on bringing her up and to provide a sense of permanence and stability in her life.[258] He had become increasingly disillusioned with cinema in the 1960s, rarely finding a script which he approved of. He remarked: "I could have gone on acting and playing a grandfather or a bum, but I discovered more important things in life".[259] He knew after he had made Charade that the "Golden Age" of Hollywood was over.[260] He expressed little interest in making a career comeback, and would respond to the suggestion with "fat chance".[261] He did, however, briefly appear in the audience of the video documentary for Elvis's 1970 Las Vegas concert Elvis: That's the Way It Is.[262] He was given the negatives from a number of his films in the 1970s, and he sold them to television for a sum of over two million dollars in 1975.[263]

Morecambe and Stirling argue that Grant's abstinence from film after 1966 was not because he had "irrevocably turned his back on the film industry", but because he was "caught between a decision made and the temptation to eat a bit of humble pie and re-announce himself to the cinema-going public".[264] In the 1970s, MGM was keen on remaking Grand Hotel (1932) and hoped to lure Grant out of retirement. Hitchcock had long wanted to make a film based on the idea of Hamlet, with Grant in the lead role.[265] Grant stated that Warren Beatty had made a big effort to get him to play the role of Mr. Jordan in Heaven Can Wait (1978), which eventually went to James Mason.[212] Morecambe and Stirling claim that Grant had also expressed an interest in appearing in A Touch of Class (1973), The Verdict (1982), and a film adaptation of William Goldman's 1983 book about screenwriting, Adventures in the Screen Trade.[264]

.jpg.webp)

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Grant became troubled by the deaths of many close friends, including Howard Hughes in 1976, Howard Hawks in 1977, Lord Mountbatten and Barbara Hutton in 1979, Alfred Hitchcock in 1980, Grace Kelly and Ingrid Bergman in 1982, and David Niven in 1983. At the funeral of Mountbatten, he was quoted as remarking to a friend: "I'm absolutely pooped, and I'm so goddamned old…. I'm going to quit all next year. I'm going to lie in bed…. I shall just close all doors, turn off the telephone, and enjoy my life".[266] Grace Kelly's death was the hardest on him as it was unexpected, and the two had remained close friends after filming To Catch a Thief.[lower-alpha 25] Grant visited Monaco three or four times each year during his retirement,[268] and showed his support for Kelly by joining the board of the Princess Grace Foundation.[267]

In 1980, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art put on a two-month retrospective of more than 40 of Grant's films.[269] In 1982, he was honored with the "Man of the Year" award by the New York Friars Club at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel.[270] He turned 80 in 1984, and Peter Bogdanovich noticed that a "serenity" had come over him.[271] Grant was in good health until suffering a mild stroke in October that year.[272] In the last few years of his life, he undertook tours of the United States in the one-man show A Conversation with Cary Grant, in which he would show clips from his films and answer audience questions.[273][274] He made some 36 public appearances in his last four years, from New Jersey to Texas, and his audiences ranged from elderly film buffs to enthusiastic college students discovering his films for the first time. Grant admitted that the appearances were "ego-fodder", remarking that "I know who I am inside and outside, but it's nice to have the outside, at least, substantiated".[275]

Business interests

Stirling refers to Grant as "one of the shrewdest businessmen ever to operate in Hollywood".[276] His long-term friendship with Howard Hughes from the 1930s onward saw him invited into the most glamorous circles in Hollywood and their lavish parties.[277] Biographers Morecambe and Stirling state that Hughes played a major role in the development of Grant's business interests so that by 1939, he was "already an astute operator with various commercial interests".[278] Scott also played a role, encouraging Grant to invest his money in shares, making him a wealthy man by the end of the 1930s.[139] In the 1940s, Grant and Barbara Hutton invested heavily in real estate development in Acapulco at a time when it was little more than a fishing village,[279] and teamed up with Richard Widmark, Roy Rogers, and Red Skelton to buy a hotel there.[280] Behind his business interests was a particularly intelligent mind, to the point that his friend David Niven once said: "Before computers went into general release, Cary had one in his brain".[278] Film critic David Thomson believes that Grant's intelligence came across on screen, and stated that "no one else looked so good and so intelligent at the same time".[281]

After Grant retired from the screen, he became more active in business. He accepted a position on the board of directors at Fabergé.[282] This position was not honorary, as some had assumed; Grant regularly attended meetings and traveled internationally to support them.[283] His pay was modest in comparison to the millions of his film career, a salary of a reported $15,000 a year.[284] Such was Grant's influence on the company that George Barrie once claimed that Grant had played a role in the growth of the firm to annual revenues of about $50 million in 1968, a growth of nearly 80% since the inaugural year in 1964.[285] The position also permitted the use of a private plane, which Grant could use to fly to see his daughter wherever her mother, Dyan Cannon, was working.[286]

In 1975, Grant was an appointed director of MGM. In 1980, he sat on the board of MGM Films and MGM Grand Hotels following the division of the parent company. He played an active role in the promotion of MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas when opened in 1973, and he continued to promote the city throughout the 1970s.[287] When Allan Warren met Grant for a photo shoot that year he noticed how tired Grant looked, and his "slightly melancholic air".[288] Grant later joined the boards of Hollywood Park, the Academy of Magical Arts (The Magic Castle, Hollywood, California), and Western Airlines (acquired by Delta Air Lines in 1987).[273]

Personal life

Grant became a naturalized United States citizen on June 26, 1942, at which time he also legally changed his name to "Cary Grant".[289][290] At the time of his naturalization, he listed his middle name as "Alexander" rather than "Alec".[5]

One of the wealthiest stars in Hollywood, Grant owned houses in Beverly Hills, Malibu, and Palm Springs.[291] He was immaculate in his personal grooming, and Edith Head, the renowned Hollywood costume designer, appreciated his "meticulous" attention to detail and considered him to have had the greatest fashion sense of any actor she had worked with.[292] McCann attributed his "almost obsessive maintenance" with tanning, which deepened the older he got,[293] to Douglas Fairbanks, who also had a major influence on his refined sense of dress.[294] McCann notes that because Grant came from a working-class background and was not well educated, he made a particular effort over the course of his career to mix with high society and absorb their knowledge, manners and etiquette to compensate and cover it up.[295] His image was meticulously crafted from the early days in Hollywood, where he would frequently sunbathe and avoid being photographed smoking, despite smoking two packs a day at the time.[296] Grant quit smoking in the early 1950s through hypnotherapy.[297] He remained health conscious, staying very trim and athletic even into his late career, though Grant admitted he "never crook[ed] a finger to keep fit".[298] He claimed that he did "everything in moderation. Except making love."[299]

Grant's daughter Jennifer stated that her father made hundreds of friends from all walks of life, and that their house was frequently visited by the likes of Frank and Barbara Sinatra, Quincy Jones, Gregory Peck and his wife Veronique, Johnny Carson and his wife, Kirk Kerkorian and Merv Griffin. She said that Grant and Sinatra were the closest of friends and that the two men had a similar radiance and "indefinable incandescence of charm", and were eternally "high on life".[300] While raising Jennifer, Grant archived artifacts of her childhood and adolescence in a bank-quality, room-sized vault he had installed in the house. Jennifer attributed this meticulous collection to the fact that artifacts of his own childhood had been destroyed during the Luftwaffe's bombing of Bristol in World War II (an event that also claimed the lives of his uncle, aunt, cousin, and the cousin's husband and grandson), and he may have wanted to prevent her from experiencing a similar loss.[301]

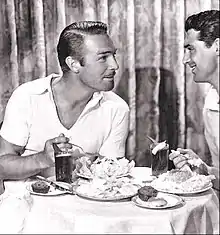

Grant lived with actor Randolph Scott off and on for 12 years, which some claimed was a gay relationship.[302] The two met early on in Grant's career in 1932 at the Paramount studio when Scott was filming Sky Bride while Grant was shooting Sinners in the Sun, and moved in together soon afterwards.[303] Scott's biographer Robert Nott states that there is no evidence that Grant and Scott were homosexual, and blames rumors on material written about them in other books.[304] Grant's daughter, Jennifer, also denied the claims.[305] When Chevy Chase joked on television in 1980 that Grant was a "homo. What a gal!", Grant sued him for slander, and Chase was forced to retract his words.[306] Grant became a fan of the comedians Morecambe and Wise in the 1960s, and remained friends with Eric Morecambe until his death in 1984.[307]

Grant began experimenting with the drug LSD in the late 1950s,[308] before it became popular. His wife at the time, Betsy Drake, displayed a keen interest in psychotherapy, and through her Grant developed a considerable knowledge of the field of psychoanalysis. Radiologist Mortimer Hartman began treating him with LSD in the late 1950s, with Grant optimistic that the treatment could make him feel better about himself and rid of all of his inner turmoil stemming from his childhood and his failed relationships. He had an estimated 100 sessions over several years.[309] For a long time, Grant viewed the drug positively, and stated that it was the solution after many years of "searching for his peace of mind", and that for first time in his life he was "truly, deeply and honestly happy".[309] Dyan Cannon claimed during a court hearing that he was an "apostle of LSD", and that he was still taking the drug in 1967 as part of a remedy to save their relationship.[310] Grant later remarked that "taking LSD was an utterly foolish thing to do but I was a self-opinionated boor, hiding all kinds of layers and defences, hypocrisy and vanity. I had to get rid of them and wipe the slate clean."[311]

Relationships

Grant was married five times.[312] He wed Virginia Cherrill on February 9, 1934, at the Caxton Hall registry office in London.[313] She divorced him on March 26, 1935,[314] following charges that he had hit her.[315] The two were involved in a bitter divorce case which was widely reported in the press, with Cherrill demanding $1,000 a week from him in benefits from his Paramount earnings.[108] After the demise of the marriage, he dated actress Phyllis Brooks from 1937. They considered marriage and vacationed together in Europe in mid-1939, visiting the Roman villa of Dorothy di Frasso in Italy, but the relationship ended later that year.[316]

He married Barbara Hutton in 1942,[317] one of the wealthiest women in the world following a $50 million inheritance from her grandfather Frank Winfield Woolworth.[318] They were derisively nicknamed "Cash and Cary",[319] although Grant refused any financial settlement in a prenuptial agreement[320] to avoid the accusation that he married for money.[lower-alpha 26] Towards the end of their marriage they lived in a white mansion at 10615 Bellagio Road in Bel Air.[322] They divorced in 1945, although they remained the "fondest of friends".[323] He dated Betty Hensel for a period,[324] then married Betsy Drake on December 25, 1949, the co-star of two of his films. This proved to be his longest marriage,[325] ending on August 14, 1962.[326]

Grant married Dyan Cannon on July 22, 1965, at Howard Hughes' Desert Inn in Las Vegas,[327] and their daughter Jennifer was born on February 26, 1966, his only child;[2] he frequently called her his "best production".[328] He said of fatherhood:

My life changed the day Jennifer was born. I've come to think that the reason we're put on this earth is to procreate. To leave something behind. Not films, because you know that I don't think my films will last very long once I'm gone. But another human being. That's what's important.[329]

Grant and Cannon divorced in March 1968.[330] On March 12, he was involved in a car accident on Long Island when a truck hit the side of his limousine. Grant was hospitalized for 17 days with three broken ribs and bruising.[331]

Grant had a brief affair with actress Cynthia Bouron in the late 1960s.[332] He had been at odds with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences since 1958, but he was named as the recipient of an Academy Honorary Award in 1970.[333] Grant announced that he would attend the awards ceremony to accept his award, thus ending his 12-year boycott of the ceremony. Two days after this announcement, Bouron filed a paternity suit against him and publicly stated that he was the father of her seven-week-old daughter,[333][lower-alpha 27] and she named him as the father on the child's birth certificate.[335] Grant challenged her to a blood test and Bouron failed to provide one, and the court ordered her to remove his name from the certificate.[335][336][lower-alpha 28] Between 1973 and 1977, he dated British photojournalist Maureen Donaldson,[338] followed by the much younger Victoria Morgan.[339]

On April 11, 1981, Grant married Barbara Harris, a British hotel public relations agent who was 47 years his junior.[340] The two had met in 1976 at the Royal Lancaster Hotel in London where Harris was working at the time and Grant was attending a Fabergé conference. They became friends, but it was not until 1979 that she moved to live with him in California. Grant's friends felt that she had a positive impact on him, and Prince Rainier of Monaco remarked that Grant had "never been happier" than he was in his last years with her.[341]

Death

—Grant on death, later in life.[342]

Grant was at the Adler Theater in Davenport, Iowa, on the afternoon of November 29, 1986, preparing for his performance in A Conversation with Cary Grant when he was taken ill; he had been feeling unwell as he arrived at the theater. Basil Williams photographed him there and thought that he still looked his usual suave self, but he noticed that he seemed very tired and that he stumbled once in the auditorium. Williams recalls that Grant rehearsed for half an hour before "something seemed wrong" all of a sudden, and he disappeared backstage. Grant was taken back to the Blackhawk Hotel where he and his wife had checked in, and a doctor was called and discovered that Grant was having a massive stroke, with a blood pressure reading of 210 over 130. Grant refused to be taken to the hospital. The doctor recalled: "The stroke was getting worse. In only fifteen minutes he deteriorated rapidly. It was terrible watching him die and not being able to help. But he wouldn't let us." By 8:45 p.m., Grant had slipped into a coma and was taken to St. Luke's Hospital.[343] He spent 45 minutes in emergency before being transferred to intensive care. He died at 11:22 p.m., aged 82.[344]

An editorial in The New York Times stated: "Cary Grant was not supposed to die. ... Cary Grant was supposed to stick around, our perpetual touchstone of charm and elegance and romance and youth."[345] His body was taken back to California, where it was cremated and his ashes scattered in the Pacific Ocean.[346] No funeral was conducted for him following his request, which Roderick Mann remarked was appropriate for "the private man who didn't want the nonsense of a funeral."[347] His estate was worth in the region of 60 to 80 million dollars;[348] the bulk of it went to Barbara Harris and Jennifer.[274]

Screen persona

McCann wrote that one of the reasons why Grant's film career was so successful is that he was not conscious of how handsome he was on screen, acting in a fashion which was most unexpected and unusual from a Hollywood star of that period.[349] George Cukor once stated: "You see, he didn't depend on his looks. He wasn't a narcissist, he acted as though he were just an ordinary young man. And that made it all the more appealing, that a handsome young man was funny; that was especially unexpected and good because we think, 'Well, if he's a Beau Brummel, he can't be either funny or intelligent', but he proved otherwise".[349] Jennifer Grant acknowledged that her father neither relied on his looks nor was a character actor, and said that he was just the opposite of that, playing the "basic man".[350]

Grant's appeal was unusually broad among both men and women. Pauline Kael remarked that men wanted to be him and women dreamed of dating him. She noticed that Grant treated his female co-stars differently than many of the leading men at the time, regarding them as subjects with multiple qualities rather than "treating them as sex objects".[100] David Shipman writes that "more than most stars, he belonged to the public".[351] A number of critics have argued that Grant had the rare star ability to turn a mediocre picture into a good one. Philip T. Hartung of The Commonweal stated in his review for Mr. Lucky (1943) that, if it "weren't for Cary Grant's persuasive personality, the whole thing would melt away to nothing at all".[352] Political theorist C. L. R. James saw Grant as a "new and very important symbol", a new type of Englishman who differed from Leslie Howard and Ronald Colman, who represented the "freedom, natural grace, simplicity and directness which characterise such different American types as Jimmy Stewart and Ronald Reagan", which ultimately symbolized the growing relationship between Britain and America.[353]

—Film critic Pauline Kael on the development of Grant's comic acting in the late 1930s[100]

McCann notes that Grant typically played "wealthy privileged characters who never seemed to have any need to work in order to maintain their glamorous and hedonistic lifestyle."[349] Martin Stirling thought that Grant had an acting range which was "greater than any of his contemporaries", but felt that a number of critics underrated him as an actor. He believes that Grant was always at his "physical and verbal best in situations that bordered on farce".[354] Charles Champlin identifies a paradox in Grant's screen persona, in his unusual ability to "mix polish and pratfalls in successive scenes". He remarks that Grant was "refreshingly able to play the near-fool, the fey idiot, without compromising his masculinity or surrendering to camp for its own sake."[355] Wansell further notes that Grant could, "with the arch of an eyebrow or the merest hint of a smile, question his own image".[356] Stanley Donen stated that his real "magic" came from his attention to minute details and always seeming real, which came from "enormous amounts of work" rather than being God-given.[357] Grant remarked of his career: "I guess to a certain extent I did eventually become the characters I was playing. I played at being someone I wanted to be until I became that person, or he became me".[358] He professed that the real Cary Grant was more like his scruffy, unshaven fisherman in Father Goose than the "well-tailored charmer" of Charade.[359]

Grant often poked fun at himself with statements such as, "Everyone wants to be Cary Grant—even I want to be Cary Grant",[360] and in ad-lib lines such as in His Girl Friday (1940): "Listen, the last man who said that to me was Archie Leach, just a week before he cut his throat."[361] In Arsenic and Old Lace (1944), a gravestone is seen bearing the name Archie Leach.[362][363] Alfred Hitchcock thought that Grant was very effective in darker roles, with a mysterious, dangerous quality, remarking that "there is a frightening side to Cary that no one can quite put their finger on".[364] Wansell notes that this darker, mysterious side extended to his personal life, which he took great lengths to cover up in order to retain his debonair image.[364]

Legacy

—Biographer Graham McCann on Cary Grant.[365]

Biographers Morecambe and Stirling believe that Cary Grant was the "greatest leading man Hollywood had ever known".[366] Schickel stated that there are "very few stars who achieve the magnitude of Cary Grant, art of a very high and subtle order" and thought that he was the "best star actor there ever was in the movies".[367][368] David Thomson and directors Stanley Donen and Howard Hawks concurred that Grant was the greatest and most important actor in the history of the cinema.[132][369] He was a favorite of Hitchcock, who admired him and called him "the only actor I ever loved in my whole life",[370] and remained one of Hollywood's top box-office attractions for almost 30 years.[371] Pauline Kael stated that the world still thinks of him affectionately because he "embodies what seems a happier time−a time when we had a simpler relationship to a performer."[100]

Grant was nominated for Academy Awards for Penny Serenade (1941) and None But the Lonely Heart (1944),[372] but he never won a competitive Oscar;[lower-alpha 29][374] he received a special Academy Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1970.[213] The inscription on his statuette read "To Cary Grant, for his unique mastery of the art of screen acting with respect and affection of his colleagues". On being presented with the award, his friend Frank Sinatra announced: "No one has brought more pleasure to more people for so many years than Cary has, and nobody has done so many things so well".[375]

Grant was awarded a special plaque at the Straw Hat Awards in New York in May 1975 which recognized him as a "star and superstar in entertainment". The following August, Betty Ford invited him to give a speech at the Republican National Convention in Kansas City and to attend the Bicentennial dinner for Queen Elizabeth II at the White House that same year. He was invited to a royal charity gala in 1978 at the London Palladium. In 1979, he hosted the American Film Institute's tribute to Alfred Hitchcock, and presented Laurence Olivier with his honorary Oscar.[376]

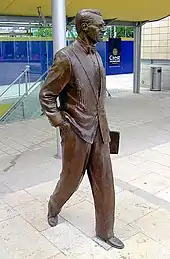

In 1981, Grant was accorded the Kennedy Center Honors.[377] Three years later, a theater on the MGM lot was renamed the "Cary Grant Theatre".[269] In 1995, more than 100 leading film directors were asked to reveal their favorite actor of all time in a Time Out poll, and Grant came second only to Marlon Brando.[378] On December 7, 2001, a statue of Grant by Graham Ibbeson was unveiled in Millennium Square, a regenerated area next to Bristol Harbour, Bristol, the city where he was born.[379] In November 2005, Grant again came first in Premiere magazine's list of "The 50 Greatest Movie Stars of All Time".[380] The biennial Cary Comes Home Festival was established in 2014 in his hometown Bristol.[381] McCann declared that Grant was "quite simply, the funniest actor cinema has ever produced".[382]

Filmography and stage work

From 1932 to 1966, Grant starred in over seventy films. In 1999, the American Film Institute named him the second greatest male star of Golden Age Hollywood cinema (after Humphrey Bogart).[383] He was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor in Penny Serenade (1941) and None but the Lonely Heart (1944).[177][384]

Widely recognized for comedic and dramatic roles, among his best-known films are Bringing Up Baby (1938), Only Angels Have Wings (1939), His Girl Friday (1940), The Philadelphia Story (1940), Arsenic and Old Lace (1944), North by Northwest (1959), and Charade (1963).[8]

Notes

- His middle name was recorded as "Alec" on birth records, although he later used the more formal "Alexander" on his naturalization application form in 1942.[3][4][5]

- Among the reasons that he gave for believing so was that he was circumcised, and circumcision was and still is rare outside the Jewish community in Britain.[14] In 1948, he donated a large sum of money to help the newly established State of Israel, declaring that it was "in the name of his dead Jewish mother".[15] He also speculated that his handsome appearance with brown curly hair could be due to his father's partly Jewish descent. There is no genealogical or substantial evidence about possible Jewish ancestry, however.[16] He turned down the leading role in Gentleman's Agreement in the 1940s, playing a non-Jewish character who pretends to be Jewish, because he believed that he could not effectively play the part. He donated considerable sums to Jewish causes over his lifetime. In 1939, he gave Jewish actor Sam Jaffe $25,000.[17]

- Wansell states that John was a "sickly child" who frequently came down with a fever. He had developed gangrene on his arms after a door was slammed on his thumbnail while his mother was holding him. She stayed up night after night nursing him, but the doctor insisted that she get some rest—and he died the night that she stopped watching over him.[10]

- Wansell notes that Grant hated mathematics and Latin and was more interested in geography, because he "wanted to travel".[36]

- Grant likely made further changes to his accent after electing to remain in the United States, in an effort to make himself more employable.[61] The slight Cockney accent that Grant had picked up during his time with the Pender troupe, blended with his efforts to sound American, resulted in his unique manner of speaking.[62]

- The play's success prompted a screen test for Grant and MacDonald by Paramount Publix Pictures at Astoria Studios in New York, which resulted in MacDonald being cast opposite Maurice Chevalier in The Love Parade (1929). Grant was rejected, and informed that his neck was "too thick" and his legs were "too bowed".[65]

- The productions included Irene, Music in May, Nina Rosa, Rio Rita, and The Three Musketeers.[74]

- Grant was later so embarrassed by the scene and he requested that it be omitted from his 1970 Academy Award footage.[78]

- Grant would later work with Gering in Devil and the Deep and Madame Butterfly (both 1932)

- Grant agreed that "Archie just doesn't sound right in America. It doesn't sound particularly right in Britain either".[83] While having dinner with Fay Wray, she suggested that he choose "Cary Lockwood", the name of his character in Nikki. Schulberg agreed the name "Cary" was acceptable, but was less satisfied with "Lockwood" as it was too similar to another actor's surname. Schulberg then gave Grant a list of surnames compiled by Paramount's publicity department, out of which he chose "Grant".[82]

- She Done Him Wrong—an adaptation of Mae West's own play Diamond Lil (1928)—was nominated in the Academy Award for Best Picture category, but lost to Cavalcade (1933).[95][96]

- According to biographer Jerry Vermilye, Grant had caught West's eye in the studio and had queried about him to one of Paramount's office boys. The boy replied, "Oh, that's Cary Grant. He's making [Madame] Butterfly with Sylvia Sidney". West then retorted, "I don't care if he's making Little Nell. If he can talk, I'll take him."[98]

- The film is ranked at 75 in AFI's 100 Years... 100 Laughs list, while West's line "Why don't you come up sometime and see me?" was voted number 26 in AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes.[102][103]

- The New York Times called Born to Be Bad a "hopelessly unintelligent hodgepodge", while Variety labelled his performance "colorless" and "meaningless".[106]

- In December 1934 Virginia Cherrill informed a jury in a Los Angeles court that Grant "drank excessively, choked and beat her, and threatened to kill her". The press continued to report on the turbulent relationship which began to tarnish his image.[108]

- Though Grant's films in the 1934–1935 period were commercial failures, he was still getting positive comments from the critics, who thought that his acting was getting better. One reviewer from Daily Variety wrote of Wings in the Dark: "Cary Grant tops all his past work. The part gave him a dimension to play with and he took it headlong. He never flaws in the moving, pathetic, but inspiring behavior of a man whose career seems ruined by an accident but comes back through a mental hell, by virtue of love and the saving ruses of friendship. His acting here lifts him definitely above his prior standing."[109] Graham Greene of The Spectator thought that he played his role in The Last Outpost "extremely well".[110]

- The pair would later on feature in Bringing Up Baby (1938), Holiday (1938) and The Philadelphia Story (1940).[114]

- The film was actually shot at Lone Pine, California in one of the largest sets ever assembled, with over 1,500 extras.[142]

- His Girl Friday is ranked number 19 on American Film Institute's 100 Years...100 Laughs and number 13 on The Guardian's list of the greatest comedy films of all time, compiled in 2010.[102][147]

- Time claim that Grant himself earned $100,000 for the film.[150]

- Critical response to the film at the time was mixed. Bosley Crowther wrote: "It is simply a concoction of crazy, fast, uninhibited farce. This sort of thing, when done well—as it generally is, in this case—can be insanely funny (if it hits right). It can also be a bore."[208]

- Grant also continued to find the experience of working with Hitchcock a positive one, remarking: "Hitch and I had a rapport and understanding deeper than words. He was a very agreeable human being, and we were very compatible ... Nothing ever went wrong. He was so incredibly well prepared. I never know anyone as capable".[211]

- Loren later professed about rejecting Grant: "At the time I didn't have any regrets, I was in love with my husband. I was very affectionate with Cary, but I was 23 years old. I couldn't make up my mind to marry a giant from another country and leave Carlo. I didn't feel like making the big step."[220]

- North by Northwest is placed at the 41st position on AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies,[228] 7th on its 100 Years...100 Thrills list,[229] and was voted the 7th greatest mystery film in its 10 Top 10 mystery films list.[230]

- Prince Rainier of Monaco, Kelly's widower, said: "Grace loved and admired Cary. She valued his friendship".[267]

- Grant was quoted as saying: "I may not have married for very sound reasons, but money was never one of them."[321]

- Grant had a reputation for filing lawsuits against the film industry since the 1930s. The basis of these suits was that he had been cheated by the respective company. Most were described as frivolous and were settled out of court. A proposal was made to present him with an Academy Honorary Award in 1969; it was vetoed by angry Academy members. The proposal garnered enough votes to pass in 1970. It is believed that Bouron's accusations were part of a smear campaign organized by those in the film industry.[334]

- In 1973, Bouron was found murdered in a San Fernando parking lot.[337]

- Jennifer Grant states that her father was quite outspoken on the discrimination that he felt against handsome men and comedians in Hollywood. He questioned "are good looks their own reward, canceling out the right to more"? She recalls that he once said of Robert Redford: "It'll be tough for him to be awarded anything, he's just too good looking".[373]

References

- Donaldson 1990..

- Sidewater, Nancy (August 7, 2009). "Cary Grant Weds Dyan Cannon (1965)". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- Eliot 2004, p. 390.

- "Index entry – Birth record list". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- McCarthy, Andy (July 1, 2016). "A Brief Passage in U.S. Immigration History". New York Public Library. Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- McCann 1997, p. 35; Nelson 2002, p. 10.

- McCann 1997, pp. 44–46.

- Wigley, Samuel (September 13, 2015). "10 great screwball comedy films". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

Wigley, Samuel (January 13, 2016). "Cary Grant: 10 essential films". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

"AFI's 10 Top 10 – Romantic Comedies". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

Hunsaker, Andy (July 5, 2012). "The 10 Essential Cary Grant Comedies – 1". IFC. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

Hunsaker, Andy (July 5, 2012). "The 10 Essential Cary Grant Comedies – 2". IFC. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016. - McCann 1997, p. 13; Eliot 2004, p. 390.

- Wansell 2011, p. 13.

- Eliot 2004, p. 24.

- Sheridan, Peter (May 26, 2017). "Family secret that left Cary Grant unable to trust women". Daily Express – via www.pressreader.com.

- Eliot 2004, p. 25.

- McCann 1997, pp. 14–15.

- Morecambe & Sterling 2004, p. 114.

- McCann 1997, p. 16.

- Higham & Moseley 1990, p. 3; McCann 1997, pp. 14–15.

- Klein 2009, p. 32.

- Weiten 1996, p. 291.

- "Cary Grant's LSD 'gateway to God'". The Sydney Morning Herald. October 18, 2011. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- Wansell 2011, p. 14.

- McCann 1997, p. 20.

- Wansell 1983, p. 32.

- McCann 1997, p. 27.

- Morecambe & Sterling 2001, p. 63.

- McCann 1997, p. 19.

- Vermilye 1973, p. 13.

- Royce & Donaldson 1989, p. 298; Nelson 2002, p. 36.

- Connolly 2014, p. 209.

- "How a surprise visit to the museum led to new discoveries". Glenside Museum. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- Wansell 2011, p. 94.

- Rood 1994, p. 140.

- Rood 1994, p. 140; Miniter 2013, p. 194.

- Fryer 2005, p. 164; Louvish 2007, p. 40; Miniter 2013, p. 194.

- McCann 1997, p. 29.

- Wansell 2011, p. 16.

- McCann 1997, p. 33.

- Ramsey, Walter (October 1933). "The Life Story of Cary Grant". Modern Screen. Dell Publications: 30. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- McCann 1997, p. 30.

- Morecambe & Sterling 2001, p. 21.

- McCann 1997, p. 34.

- McCann 1997, pp. 30-31.

- McCann 1997, p. 37.

- Fells 2015, p. 105.

- Schickel 2009, p. 29.

- McCann 1997, p. 37–38.

- Wansell 2011, p. 17.

- McCann 1997, p. 34; Nelson 2002, p. 42; Eliot 2004, p. 34.

- Schickel 1998, p. 20.

- McCann 1997, pp. 44–46; Wansell 2011, p. 17.

- McCann 1997, p. 53.

- Wansell 2011, p. 18.

- Roberts 2014, p. 100.

- McCann 1997, p. 49.

- McCann 1997, p. 51; Wansell 2011, p. 18.

- McCann 1997, p. 51.

- McCann 1997, p. 53; Roberts 2014, p. 100.

- Slide 2012, p. 211.

- Wansell 2011, pp. 18–19.

- McCann 1997, pp. 59–60; Walker 2015, p. 187.

- McCann 1997, pp. 59–60.

- Nelson 2002, pp. 55-56.

- Wansell 2011, p. 19.

- Donnelley 2003, p. 290; Wansell 2011, p. 19.

- Wansell 2011, p. 20.

- Wansell 1983, p. 75; Turk 1998, p. 350.

- McCann 1997, p. 54; Wansell 2011, p. 20.

- Traubner 2004, p. 115.

- McCann 1997, p. 55; Wansell 2011, p. 20.

- McCann 1997, p. 55.

- Wansell 2011, p. 21.

- McCann 1997, p. 56.

- Deschner 1973, p. 6.

- Botto & Viagas 2010, p. 493; Wansell 2011, p. 21.

- McCann 1997, p. 71.

- Eliot 2004, pp. 54–55.

- Bonet Mojica, Lluis (2004). Cary Grant. pp. 37–38. ISBN 84-95602-58-X.

- McCann 1997, p. 57.

- Eliot 2004, pp. 56–57.

- McCann 1997, p. 62.

- Vermilye 1973; Wansell 2011, p. 21.

- Eliot 2004, p. 57.

- McCann 1997, p. 61.

- McCann 1997, p. 65.

- McCann 1997, p. 60.

- Vermilye 1973, p. 20; Eliot 2004, p. 62.

- Eliot 2004, p. 62; Wansell 2011, p. 22.

- Eliot 2004, p. 63.

- Rothman 2014, p. 71.

- McCann 1997, p. 80.

- Wansell 2011, p. 29.

- "Cary Grant — Complete Filmography With Synopsis". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on November 16, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- Eliot 2004, pp. 63–68.

- Eliot 2004, p. 66.

- Eliot 2004, pp. 68–69.

- "The 6th Academy Awards 1934". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. March 16, 1934. Archived from the original on June 7, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- Wansell 2011, p. 30.

- Vermilye 1973, p. 30.

- McCann 1997, p. 86.

- Kael, Pauline (July 14, 1975). "The Man From Dream City". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 9, 2016. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- Wansell 2011, p. 31.

- "AFI's 100 Funniest American Movies Of All Time". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on November 16, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- "AFI's 100 Greatest Movie Quotes Of All Time". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on November 16, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- Eliot 2004, p. 73.

- Vermilye 1973, pp. 37–38; Eliot 2004, p. 91.

- Wansell 2011, p. 36.

- Halliwell 1976, p. 23.

- Wansell 2011, p. 38.

- Deschner 1973, p. 84.

- Deschner 1973, p. 86.

- Vermilye 1973, p. 48.

- Wansell 2011, p. 39.

- Vermilye 1973, pp. 48–49; Deschner 1973, pp. 88–89.

- Vermilye 1973, pp. 146–148.

- Schickel 1998, p. 46.

- Vermilye 1973, pp. 48–49; Wansell 2011, p. 41.

- McCann 1997, p. 89.

- Vermilye 1973, p. 55.

- Wansell 2011, p. 42.

- "When You're In Love — Reviews". Carygrant.net. Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- Wansell 2011, p. 43.

- Richard Jewel, 'RKO Film Grosses: 1931–1951', Historical Journal of Film Radio and Television, Vol 14 No 1, 1994 p. 57.

- Vermilye 1973, p. 58.