Women in early modern Scotland

Women in early modern Scotland, between the Renaissance of the early sixteenth century and the beginnings of industrialisation in the mid-eighteenth century, were part of a patriarchal society, though the enforcement of this social order was not absolute in all aspects. Women retained their family surnames at marriage and did not join their husband's kin groups. In higher social ranks, marriages were often political in nature and the subject of complex negotiations in which women as matchmakers or mothers could play a major part. Women were a major part of the workforce, with many unmarried women acting as farm servants and married women playing a part in all the major agricultural tasks, particularly during harvest. Widows could be found keeping schools, brewing ale and trading, but many at the bottom of society lived a marginal existence.

Women had limited access to formal education and girls benefited less than boys from the expansion of the parish school system. Some women were taught reading, domestic tasks, but often not writing. In noble households some received a private education and some female literary figures emerged from the seventeenth century. Religion may have been particularly important as a means of expression for women and from the seventeenth century women may have had greater opportunities for religious participation in movements outside of the established kirk. Women had very little legal status at the beginning of the period, unable to act as witnesses or legally responsible for their own actions. From the mid-sixteenth century they were increasingly criminalised, with statutes allowing them to be prosecuted for infanticide and as witches. Seventy-five per cent of an estimated 6,000 individuals prosecuted for witchcraft between 1563 and 1736 were women and perhaps 1,500 were executed. As a result, some historians have seen this period as characterised by increasing concern with women and attempts to control and constrain them.

Status

Early modern Scotland was a patriarchal society, in which men had total authority over women.[1] From the 1560s the post-Reformation marriage service underlined this by stating that a wife "is in subjection and under governance of her husband, so long as they both continue alive".[2] As was common in Western Europe, Scottish society stressed a daughter's duties to her father, a wife's duties to her husband and the virtues of chastity and obedience.[3] Given very high mortality rates, women could inherit important responsibilities from their fathers and from their husbands as widows. Evidence from towns indicates that around one in five households were headed by women, often continuing an existing business interest.[4][5] In noble society, widowhood created some very wealthy and powerful women, including Catherine Campbell, who became the richest widow in the kingdom when her husband, the ninth earl of Crawford, died in 1558 and the twice-widowed Margaret Ker, dowager lady Yester, described in 1635 as having "the greatest conjunct fie [fiefdom] that any lady hes in Scotland".[6]

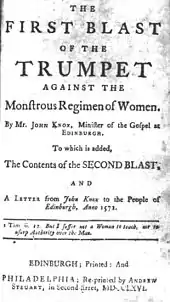

In politics the theory of patriarchy was complicated by regencies led by Margaret Tudor and Mary of Guise and by the advent of a regnant queen in Mary, Queen of Scots from 1561. Concerns over this threat to male authority were exemplified by John Knox's The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstruous Regiment of Women (1558), which advocated the deposition of all reigning queens. Most of the political nation took a pragmatic view of the situation, accepting Mary as queen, but the strains that this paradox created may have played a part in the later difficulties of the reign.[7] How exactly patriarchy worked in practice is difficult to discern. Scottish women in this period had something of a reputation among foreign observers for being forthright individuals, with the Spanish ambassador to the court of James IV noting that they were "absolute mistresses of their houses and even their husbands".[3]

Family and marriage

Unlike in England, where kinship was predominately cognatic (derived through both males and females), in Scotland kinship was agnatic, with members of a group sharing a (sometimes fictional) common ancestor. Women retained their original surname at marriage, symbolising that they did not join their husband's kin, and marriages were intended to create friendship between kin groups, rather than a new bond of kinship.[8] Women could marry from the age of 12 (while for boys it was from 14) and, while many girls from the social elite married in their teens, most in the Lowlands only married after a period of life-cycle service, in their twenties, by which they accrued resources, status and skills that would allow them to establish a household.[9] Normally marriage followed handfasting, a period of betrothal, which in the Highlands may have effectively been a period of trial marriage, in which sexual activity may have been accepted as legitimate.[10] Highland women, based on the higher birth rate of the Highlands, might have married earlier than their Lowland counterparts.[11]

Marriages, particularly higher in society, were often political in nature and the subject of complex negotiations over the tocher (dowry). Some mothers took a leading role in negotiating marriages, as Lady Glenorchy did for her children in the 1560s and 1570s, or as matchmakers, finding suitable and compatible partners for others. Before the Reformation, the extensive marriage bars for kinship meant that most noble marriages necessitated a papal dispensation, which could later be used as grounds for annulment if the marriage proved politically or personally inconvenient, although there was no divorce as such.[1] Separation from bed and board was allowed in exceptional circumstances, usually adultery. Under the reformed Kirk, divorce was allowed on grounds of adultery, or of desertion. Scotland was one of the first countries to allow desertion as legal grounds for divorce and, unlike England, divorce cases were initiated relatively far down the social scale.[12]

Work

Women acted as an important part of the workforce. In addition to the domestic tasks carried out by wives and female servants, many unmarried women worked away from their families as farm servants and married women worked with their husbands around the farm, taking part in all the major agricultural tasks. They had a particular role as shearers in the harvest, forming most of the reaping team of the bandwin. Women also played an important part in the expanding textile industries, spinning and setting up warps for men to weave. In the Highlands they may have been even more significant as there is evidence that many men considered agricultural work to be beneath their status and in places they may have formed the majority of the rural workforce.[13] There were roles that were the preserve of women alone, including as midwives and wet-nurses.[14] There is evidence of single women engaging in independent economic activity, particularly for widows, who can be found keeping schools, brewing ale and trading.[13] Some were highly successful, like Janet Fockart, an Edinburgh Wadwife or moneylender, who had been left a widow with seven children after her third husband's suicide, and who managed her business affairs so successfully that she had amassed a moveable estate of £22,000 by her death in the late sixteenth century.[15] Lower down the social scale the rolls of poor relief indicate that large numbers of widows with children endured a marginal existence and were particularly vulnerable in times of economic hardship.[13] "Masterless women", who had no responsible fathers or husbands may have made up as much as 18 per cent of all households and particularly worried authorities who gave instructions to take particular notice of them.[16]

Education and writing

By the end of the fifteenth century, Edinburgh had schools for girls, sometimes described as "sewing schools", and probably taught by lay women or nuns.[17][18] There was also the development of private tuition in the families of lords and wealthy burghers, which may have extended to women.[17] From the mid-seventeenth century there were boarding schools for girls, particularly in Edinburgh or London. These were often family-sized institutions headed by women. Initially these were aimed at the girls of noble households, but by the eighteenth century there were complaints that the daughters of traders and craftsmen were following their social superiors into these institutions.[19] By the eighteenth century many poorer girls were being taught in dame schools, informally set up by a widow or spinster to teach reading, sewing and cooking.[20]

The widespread belief in the limited intellectual and moral capacity of women, vied with a desire, intensified after the Reformation, for women to take personal moral responsibility, particularly as wives and mothers. In Protestantism this necessitated an ability to learn and understand the catechism and even to be able to independently read the Bible, but most commentators, even those that tended to encourage the education of girls, thought they should not receive the same academic education as boys. In the lower ranks of society, they benefited from the expansion of the parish schools system that took place after the Reformation, but were usually outnumbered by boys, often taught separately, for a shorter time and to a lower level. They were frequently taught reading, sewing and knitting, but not writing. Female illiteracy rates based on signatures among female servants were around 90 per cent, from the late seventeenth to the early eighteenth centuries and perhaps 85 per cent for women of all ranks by 1750, compared with 35 per cent for men.[21]

Among the nobility there were many educated and cultured women, of which Queen Mary is the most obvious example.[22] By the early eighteenth century their education was expected to include basic literacy and numeracy,[23] musical instruments (including lute, viol and keyboard),[24] needlework, cookery and household management, while polite accomplishments and piety were also emphasised.[23] From the seventeenth century they were some notable aristocratic female writers. The first book written by a woman and published in Scotland was Elizabeth Melville's Ane Godlie Dreame in 1603.[25] Later major figures included Lady Elizabeth Wardlaw (1627–1727) and Lady Grizel Baillie (1645–1746).[26] There are 50 autobiographies extant from the late seventeenth to the early eighteenth century, of which 16 were written by women, all of which are largely religious in content.[27]

Religion

Historian Katharine Glover argues that women had less means of public participation than men and that as a result piety and an active religious life may have been more important for women from the social elite. Church going played an important part in the lives of many women. Women were largely excluded from the administration of the kirk, but when heads of households voted on the appointment of a new minister some parishes allowed women in that position to participate.[28]

The upheavals of the seventeenth century saw women autonomously participating in radical religion.[28] The most prominent examples were the women who threw their cuttie-stools at the dean who was reading the new "English" service book in St. Giles Cathedral in 1637, precipitating the Bishop's Wars (1639–40), between the Presbyterian Covenanters and the king, who favoured an episcopalian structure in the church, similar to that in England. They were later said to have been led by Edinburgh woman Jenny Geddes.[29] According to R. A. Houston, women probably had more freedom of expression and control over their spiritual destiny in groups outside the established church such the Quakers, who had a presence in the country from the mid-seventeenth century.[30] The principle of male authority could be challenged when women chose different religious leaders from their husbands and fathers.[28] Among the Cameronians, who broke away from the kirk when episcopalianism was re-established at the Restoration in 1660, several reports indicate that women could preach and excommunicate, but not baptise. Several women are known to have been executed for their part in the movement.[31]

Crime and the law

At the beginning of the period, women had a very limited legal status. A married woman had few property rights and could not make a will without her husband's permission, although jurists expected this to be given.[12] Men had considerable latitude in disciplining the women under their authority and although a handful of cases turn up in higher courts, and the kirk session did intervene to protect women from domestic abuse, it was usually only when the abuse began to disturb public order.[3] The criminal courts refused to recognise women as witnesses, or as independent criminals, and responsibly for their actions was assumed to lie with their husbands, fathers and kin.[13] As a result, a married woman could not sell property, sue in court or make contracts without her husband's permission.[32]

In the post-Reformation period there was a criminalisation of women.[13] Women were disciplined in kirk sessions and civil courts for stereotypical offenses including scolding and prostitution, which were seen as deviant, rather than criminal.[33] Through the 1640s there were independent commissions set up to try women for child murder and, after pressure from the kirk, a law of 1690 placed the presumption of guilt on a woman who concealed a pregnancy and birth and whose child later died.[13] In the aftermath of the initial Reformation settlement, Parliament passed the Witchcraft Act 1563, similar to that passed in England one year earlier, which made the practice of witchcraft itself and consulting with witches capital crimes.[34] Between the passing of the act and its repeal in 1736, an estimated 6,000 persons were tried for witchcraft in Scotland.[34] Most of the accused, some 75 per cent, were women, with over 1,500 executed, and the witch hunt in Scotland has been seen as a means of controlling women.[35] Various reasons for the Scottish witch-hunt, and its more intense nature than that in England, have been advanced by historians. Many of the major periods of prosecution coincided with periods of intense economic distress[36] and some accusations may have followed the withdrawal of charity from marginal figures, particularly the single women that made up many of the accused.[37] Changing attitudes to women, particularly in the reformed kirk, which may have perceived women as more of a moral threat, have also been noted.[38] The proliferation of partial explanations for the witch hunt has led some historians to proffer the concept of "associated circumstances", rather than one single significant cause.[38]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Women of Scotland. |

References

Notes

- J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0-7486-1455-9, pp. 62–3.

- E. P. Dennison, "Women: 1 to 1700", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 645–6.

- E. Ewen, "The early modern family" in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0-19-956369-1, p. 274.

- M. Lynch, The Early Modern Town in Scotland (London: Taylor & Francis, 1987), ISBN 0-7099-1677-9, p. 208.

- Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, p. 22.

- K. Brown, Noble Society in Scotland: Wealth, Family and Culture from Reformation to Revolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0-7486-1299-8, p. 73.

- Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, p. 243.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 29–35.

- Ewen, "The early modern family", p. 271.

- Ewen, "The early modern family", p. 272.

- A. Lawrence, "Women in the British Isles in the sixteenth century", in R. Tittler and N. Jones, eds, A Companion to Tudor Britain (Oxford: Blackwell John Wiley & Sons, 2008), ISBN 1405137401, p. 384.

- Ewen, "The early modern family", p. 273.

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 0-7486-0233-X, pp. 86–8.

- Ewen, "The early modern family", p. 277.

- Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, p. 322.

- M. Lynch, "Preaching to the converted?: perspectives on the Scottish Reformation", in A. Alasdair A. MacDonald, M. Lynch and I. B. Cowan, The Renaissance in Scotland: Studies in Literature, Religion, History, and Culture Offered to John Durkhan (BRILL, 1994), ISBN 90-04-10097-0, p. 340.

- P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), ISBN 1-84384-096-0, pp. 29–30.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (Random House, 2011), ISBN 1-4464-7563-8, pp. 104–7.

- K. Glover, Elite Women and Polite Society in Eighteenth-Century Scotland (Boydell Press, 2011), ISBN 1-84383-681-5, p. 36.

- B. Gatherer, "Scottish teachers", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, Scottish Education: Post-Devolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1625-X, p. 1022.

- R. A. Houston, Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-521-89088-8, pp. 63–8.

- Brown, Noble Society in Scotland, p. 187.

- K. Glover, Elite Women and Polite Society in Eighteenth-Century Scotland (Boydell Press, 2011), ISBN 1-84383-681-5, p. 26.

- D. Mackinnon, "'I now have a book of songs of her writing': Scottish families, orality, literacy and the transmission of musical culture c. 1500-c. 1800", in E. Ewan and J. Nugent, Finding the Family in Medieval and Early Modern Scotland (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2008), ISBN 0-7546-6049-4, p. 45.

- I. Mortimer, The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England (Random House, 2012), ISBN 1-84792-114-0, p. 70.

- R. Crawford, Scotland's Books: a History of Scottish Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), ISBN 0-19-538623-X, pp. 224, 248 and 257.

- D. G. Mullan, Women's Life Writing in Early Modern Scotland: Writing the Evangelical Self, C. 1670-c. 1730 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003), ISBN 0-7546-0764-X, p. 1.

- K. Glover, Elite Women and Polite Society in Eighteenth-Century Scotland (Boydell Press, 2011), ISBN 1-84383-681-5, p. 135.

- M. Bennett, The Civil Wars Experienced: Britain and Ireland, 1638–1661 (London: Routledge, 2005), ISBN 1-134-72454-3, p. 2.

- R. A. Houston, "Women in the economy and society in Scotland" in R. A. Houston and I. D. Whyte, Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-521-89167-1, p. 137.

- R. L. Greaves, Secrets of the Kingdom: British Radicals from the Popish Plot to the Revolution of 1688–1689 (Stanford University Press, 1992), ISBN 0-8047-2052-5, p. 75.

- Ewen, "The early modern family", p. 275.

- A.-M. Kilday, Women and Violent Crime in Enlightenment Scotland (London: Boydell & Brewer, 2007), ISBN 0-86193-287-0, p. 19.

- K. A. Edwards, "Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart Scotland", in K. Cartwright, A Companion to Tudor Literature Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2010), ISBN 1-4051-5477-2, p. 32.

- S. J. Brown, "Religion and society to c. 1900", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0-19-956369-1, p. 81.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community, pp. 168–9.

- L. Martin, "The Devil and the domestic: witchcraft, quarrels and women's work in Scotland", in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7190-6024-9, p. 75.

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 0-7486-0233-X, pp. 88–9.

Bibliography

- Bawcutt, P. J. and Williams, J. H., A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), ISBN 1-84384-096-0.

- Bennett, M., The Civil Wars Experienced: Britain and Ireland, 1638–1661 (London: Routledge, 2005), ISBN 1-134-72454-3.

- Brown, K., Noble Society in Scotland: Wealth, Family and Culture from Reformation to Revolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0-7486-1299-8.

- Brown, S. J., "Religion and society to c. 1900", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0-19-956369-1.

- Crawford, R., Scotland's Books: a History of Scottish Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), ISBN 0-19-538623-X.

- Dawson, J. E. A., Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0-7486-1455-9.

- Dennison, E. P., "Women: 1 to 1700", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- Edwards, K. A., "Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart Scotland", in K. Cartwright, A Companion to Tudor Literature Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2010), ISBN 1-4051-5477-2.

- Ewen, E., "The early modern family" in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0-19-956369-1.

- Gatherer, B., "Scottish teachers", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, Scottish Education: Post-Devolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1625-X.

- Glover, K., Elite Women and Polite Society in Eighteenth-Century Scotland (Boydell Press, 2011), ISBN 1-84383-681-5.

- Greaves, R. L., Secrets of the Kingdom: British Radicals from the Popish Plot to the Revolution of 1688–1689 (Stanford University Press, 1992), ISBN 0-8047-2052-5, p. 75.

- Houston, R. A., "Women in the economy and society in Scotland" in R. A. Houston and I. D. Whyte, ed., Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-521-89167-1.

- Houston, R. A., Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-521-89088-8.

- Kilday, A.-M., Women and Violent Crime in Enlightenment Scotland (London: Boydell & Brewer, 2007), ISBN 0-86193-287-0.

- Lynch, M., "Preaching to the converted?: perspectives on the Scottish Reformation", in A. Alasdair A. MacDonald, M. Lynch and I. B. Cowan, The Renaissance in Scotland: Studies in Literature, Religion, History, and Culture Offered to John Durkhan (BRILL, 1994), ISBN 90-04-10097-0.

- Lynch, M., Scotland: A New History (Random House, 2011), ISBN 1-4464-7563-8.

- Lynch, M., The Early Modern Town in Scotland (London: Taylor & Francis, 1987), ISBN 0-7099-1677-9.

- Mackinnon, D., "'I now have a book of songs of her writing': Scottish families, orality, literacy and the transmission of musical culture c. 1500-c. 1800", in E. Ewan and J. Nugent, Finding the Family in Medieval and Early Modern Scotland (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2008), ISBN 0-7546-6049-4.

- Martin, L., "The Devil and the domestic: witchcraft, quarrels and women's work in Scotland", in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7190-6024-9..

- Mitchison, R., Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 0-7486-0233-X.

- Mortimer, I., The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England (Random House, 2012), ISBN 1-84792-114-0, p. 70.

- Mullan, D. G., Women's Life Writing in Early Modern Scotland: Writing the Evangelical Self, C. 1670-c. 1730 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003), ISBN 0-7546-0764-X.

- Wormald, J., Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3.