Woylie

The woylie or brush-tailed bettong (Bettongia penicillata) is an extremely rare, small marsupial, belonging to the genus Bettongia, that is endemic to Australia. There are two subspecies: B. p. ogilbyi, and the now extinct B. p. penicillata.

| Woylie | |

|---|---|

1.jpg.webp) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Potoroidae |

| Genus: | Bettongia |

| Species: | B. penicillata |

| Binomial name | |

| Bettongia penicillata | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

.PNG.webp) | |

| Historic woylie range in yellow, current range in red | |

Taxonomy

A species was first described by J. E. Gray in 1837,[2] based on the skin and skull of an adult male obtained by the Zoological Society of London, and placed with the British Museum of Natural History.[3] The origin of the holotype has not been determined, but it is presumed to be New South Wales.[4][5]

The two subspecies recognised are

- Bettongia penicillata ogilbyi (Waterhouse, 1841)

A description published as Hypsiprymnus ogilbyi, a species now recognised as the only extant subspecies of B. penicillata. The cited author is G. R. Waterhouse, who presented a manuscript prepared by John Gould. The type was collected at York, Western Australia.[6]

- Bettongia penicillata penicillata J.E. Gray, 1837. The nominate subspecies, classified as a modern extinction.

The common name, "woylie", is derived from walyu in the Nyungar language.[7] The regional variants amongst Nyungar peoples are noted as wol, woli and woylie. The spelling woylie, and its variants, were used for the species in reports and advertisements in Western Australian newspapers, and the spelling 'woylye' was added in the 1920s.[8] The names boodie and boodie rat came to be applied by the rural inhabitants to several species in south-west Australia, including the woylie, and printed in references to them after 1897. However, the boodie (Bettongia lesueur) is now recognised as a separate species. The term "kangaroo rat" was also applied from the founding of the Swan River Colony, and was sometimes used to distinguish the species from the boodie. Another vernacular term applied to the woylie was "farting rat", inspired by the abrupt noise it emits when disturbed.[8]

Description

Bettongia penicillata is a species of potoroine marsupial that digs for fungi during the night, usually maintaining a solitary range around a central nest. The length of the head and body combined is 310 to 380 millimetres, entirely covered in fur that is a grey-brown over the back, a buff colour across the face, thigh and flank, and blending to the pale cream colour beneath. The greyish brown of the upper-parts of the pelage is interspersed with silvery hair. The tail is a similar length to the head and body, measuring from 290 to 350 mm, and is a rufous brown colour that ends in a blackish tip. The upper-side of the slightly prehensile tail has a ridge of longer fur along its length.[9] The average measurements are 330 mm for the heady-body length and , 310 mm for the tail. The average weight is 1300 grams.[10]

This species resembles the burrowing boodie (Bettongia lesueur), although the woylie is distinctly paler at the ventral side, and lacks the blackish colour of the boodie's tail. The ring around the eye of the woylie is pale, and its muzzle is longer and more pointed than the boodie, and less than Gilbert's potoroo (Potorous gilbertii), with which it once shared an overlapping distribution range.[9]

Distribution and habitat

The woylie was abundant in the mid-19th century, inhabiting a range covering around 60% of the Australian mainland, including all of the south-west of Eastern Australia, most of South Australia, the north-west corner of Victoria, and across the central portion of New South Wales. The population in south-west Australia persisted into the twentieth century, seemingly surviving the mass extinction of similar mammals in the previous decades, and was collected at temperate locations near Margaret River, by G. C. Shortridge in 1909, and by Charles M. Hoy in 1920. The last collections made at King George Sound and the Denmark regions of Western Australia in the 1930s coincided with the earliest records of the introduced red fox (Vulpes vulpes), which was first seen at Perth in 1927, and in the south not long thereafter.[11]

By the 1920s, the woylie was extinct over much of its range. As of 1992, it was reported from only four small areas in Western Australia. In South Australia, several populations have been established through reintroduction of captive-bred animals. As of 1996, it occurred in only six sites in Western Australia, including Karakamia Sanctuary, run by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy, and on three islands and two mainland sites in South Australia, following a reintroduction program after foxes had been controlled.

By 2010, one of the remaining thriving habitats for the woylie was the Dryandra Woodland south of Perth in Western Australia. The state-sponsored control of foxes offered new hope for the species, but along with the native numbat, numbers were decimated by feral cats, which flourished after fox numbers were brought under control. A major program to control feral cats has seen the number of both woylies and numbats begin to increase, although populations remain vastly reduced from even recent decades.[12]

Today, the species lives mostly in open sclerophyll forest and Mallee Woodlands and Shrublands eucalypt assemblages, with a dense low understory of tussock grasses.[13] However, this versatile species is also known to have once inhabited a wide range of habitats, including low arid scrub or desert spinifex grasslands.[1]

The dispersal of many potoroine species from their place of birth appears to be by sub-adult males acquiring a new territory. That has been recorded in these species when they reoccupy an area subjected to fire that had killed the previous residents.[14]

Diet

As with the Potoroos and other Bettongia species, the woylie has a largely fungivorous diet and will dig for a wide variety of their fruiting bodies.[15] Although it may eat tubers, seeds, insects, and resin exuded from Hakea laurina, the bulk of its nutrients are derived from underground fungi, which it digs out with its strong fore-claws. The fungi can only be digested indirectly. They are consumed by bacteria in a portion of its stomach. The bacteria produce the nutrients that are digested in the rest of the animal's stomach and small intestine. When it was widespread and abundant, the woylie probably played an important role in the dispersal of fungal spores within desert ecosystems.[16]

The austral summer and autumn seasons provide woylies with the fruiting bodies of hypogeous fungi, and around 24 fungal taxa are known to be consumed. During the summer months, species of the truffle-like Mesophellia form the major part of the diet. The core of the truffles of Mesophellia is consumed by woylies, which avoid the hard outer layer, and has been analysed for its nutritional value. The food is a rich source of lipids and trace elements accumulated by the fungus, and high protein levels that lack the required lycine and other amino acids, may be compensated by fermentation processes on the available aminos cysteine and methionine within the digestion. In other seasons, woylies may adopt a more herbivorous range of foods in addition to that season's hypogeous fungal bodies.[17]

Woylies have been observed eating the large seeds of Australian sandalwood, Santalum spicatum, a nutritious food that the animal is known to place in a shallow cache for later consumption. The habit of caching the seeds is likely to have played an important role in the dispersal of the tree. However, Australian sandalwood was a commercially valuable tree, and was extensively cleared during colonisation. Populations of woylies introduced to an island off the coast of South Australia consume mainly plant material, tubers and roots, seeds and leaves, and beetles, a diet regarded as unusual for the species. Analysis of that colony's diet showed that it included fungal spores, as detected in their scats, although that is likely to have been an occupant of the guts of the beetles.[18]

Ecology

Woylies were well known to the first European settlers of rural Western Australia. The species was used for meat during the earlier colonial period, although that practice did not persist amongst the colonists because, while it was readily available and easily captured, the skinning of the animal is said to be difficult. At one time, woylies were kept as pets in the same region. Although similar species of marsupials were often regarded as agricultural pests, the woylie did not always acquire this reputation, and was sometimes identified as a non-destructive native animal.[8]

Native predators of the woylie include the wedge-tailed eagle Aquila audax, a large raptor thought to have been a significant influence on their mortality.[8] The red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and cat (Felis catus), which arrived with Europeans, are known to prey on this species, and both have been cited as a major cause of local extinctions. Since the control of the red fox, the cat has become the major predator of the species.[19][12]

Behaviour

Woylies are largely nocturnal, resting during the day and emerging around dusk rather than after sunset, unlike the strictly nocturnal rufous bettong Aepyprymnus rufescens, although woylies always returns to their nest before dawn.[20] They can breed all year round if the conditions are favourable. The female is fertile at six months of age and gives birth every 3.5 months. Its lifespan in the wild is about four to six years.[13]

The woylie builds its dome-shaped nest in a shallow scrape under a bush, and is able to curl its tail to carry bundles of nesting material. The nest, which consists of grass and shredded bark, sticks, leaves and other available material, is well made and discreet.

The species behaves in a characteristic way when disturbed at its nest, rapidly leaving the site with an explosive noise.[8] The body is arched as the animal hops away, with the head held low and the tail extended, using a bipedal motion in lengthy bounds to evade a potential predator.[9]

A broad foraging area is occupied by individuals, with a larger area for the male, and these will likely overlap with the larger range of other woylies. Within the range, each animal defends a smaller central territory which only overlaps between males and females. Several nests within a range may provide casual and communal accommodation; only a central nest site is defended to the exclusion of any other. Measurements of the nest territory and foraging ranges of individuals has given variable results. An early study at an open woodland suggested an area of 15 to 28 hectares around the nest site for the female and 28 to 43 ha for the male. The central range seemed to extend around the nest for 4 to 6 ha. A subsequent survey calculated an exclusive zone around the nest of 2 to 3 ha for the male, and the foraging area as 27 ha for the male and 20 ha for the female. An analysis of a radio-tracking survey also indicated a nest range of 2 to 3 ha, yet a smaller foraging range of 7 to 9 ha for the species.[21]

Population collapse

.JPG.webp)

The woylie was originally found in great abundance across southern Australia, north to about 30°S, in a wide distribution range from the coast in the west and east toward the Great Dividing Range.[22]

The species was observed at all parts of the Swan River Colony when the field worker John Gilbert visited during its founding years. Gilbert noted woylies on the tidal flats of the Swan Coastal Plain and river itself, and their nests amongst clumps of grass and the hollows of trees, observing a preference for woodlands of Eucalyptus wandoo.[8] As late as 1910, the population was said to be well known in the Australian south-west, and interviews with older residents helped to establish the time and pattern of decline. The sudden demise of local populations near settlements across the state was noticed by the inhabitants, with most vanishing in the 1930s, while some persisted in a few regions until the 1950s.

The last sighting of a woylie a Bridgetown, Western Australia was in 1912. In some areas, that was recalled as following the earlier disappearance of the boodie. The decline was probably caused by a number of factors, including the impact of introduced grazing animals, accompanied by land clearance for pastoralism and agriculture. As has been noted, predation by introduced red foxes[23] and feral cats[12] has undoubtedly been crucial. The introduction of the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), may have also placed the population under pressure, especially in arid and semi-arid regions, by direct competition or the dilapidation of the ecology.[24] Changed fire regimes might also have played a part. The species suffered localised extinctions throughout its range, and was highly endangered by the 1970s.

Conservation

Conservation efforts in the late 20th century concentrated on reintroducing woylies to sites in their former range, after controlling red foxes. Stable populations were established in places such as Venus Bay, St Peter Island and Wedge Island in South Australia, Shark Bay in Western Australia, and Scotia Sanctuary in New South Wales. As a result of those efforts, the woylie population rose to sufficient numbers that it was taken off the threatened species list in 1996. The population expanded, with new, wild-born joeys being recorded as surviving several drought years in the early 2000s. The total population of the species rose to 40,000 by 2001.

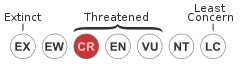

However, another sudden decline occurred in late 2001, and in just five years, the woylie population dropped to only 10-30% of its pre-2001 numbers. It was returned to the IUCN Red List as critically endangered. The exact cause of the rapid population crash was uncertain, although researcher Andrew Thompson found two parasite infestations in woylie blood.[25] Predation and habitat destruction were also suggested as contributing to the decline of the species.[26] In 2011, the global population was estimated to be less than 5,600 individuals.[1] It was hypothesised in 2013 that disease within populations was making them more vulnerable to predation.[27]

Despite those declines, woylies continued as small localized populations in predator-free sanctuaries, including a population established in 2010 at Wadderin Sanctuary in the central Western Australian wheatbelt.[28] The reintroduction of control programs for predators saw the species successfully conserved at sites including Perup, Tutanning and the Dryandra Woodland reserves.[9] In the Dryandra Woodland, woylie numbers, which had been decimated by hundreds of feral cats, were reported to be recovering after the introduction of a state-sponsored cat baiting and trapping program, supported by the adjacent farming community. It was discovered that most of the feral cats were living and breeding on surrounding farms, and then entering the woodland to kill the native animals.[12]

The species has become established at a large fenced reserve at Western Australia's Mount Gibson Sanctuary[29] and there are plans in process to reintroduce it to Dirk Hartog Island[30] following the complete removal of feral cats and livestock. It is also pegged for reintroduction to fenced landscapes at Newhaven[31] in the Northern Territory, and Mallee Cliffs National Park[32] and the Pilliga Forest[33] - both in New South Wales.

It will be a key species in the Great Southern Ark faunal reconstruction project on South Australia's Yorke Peninsula, where its reintroduction will be supported by large-scale fencing and the baiting of feral cats and foxes.[34]

References

- Claridge, A.W.; Seebeck, J.H.; Rose, R. (2007). Bettongs, potoroos, and the musky rat-kangaroo. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Pub. ISBN 9780643093416.

- Wayne, A.; Friend, T.; Burbidge, A.; Morris, K. & van Weenen, J. (2008). "Bettongia penicillata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2008.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Database entry includes justification for why this species is listed as critically endangered

- Gray, J.E. (1837). "Bettongia penicillata". Magazine of Natural History and Journal of Zoology, Botany, Mineralogy, Geology and Meteorology. 1 New Series (2): 584.

- "Subspecies Bettongia penicillata penicillata J.E. Gray, 1837". Australian Faunal Directory. biodiversity.org.au. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- Claridge 2007, p. 5.

- Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Diprotodontia". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Waterhouse, 1841., G.R. (1841). "The natural history of Marsupialia or pouched animals". In Jardine, W. (ed.). The Naturalist's Library. Mammalia. 11 (1 ed.). Edinburgh & London: W.H. Lizars & H.G. Bohn. p. 185.

- "Aboriginal Words in the English Language: L-Z". One Big Garden. Retrieved 12 Sep 2012.

- Abbott, I. (2008). "Historical perspectives of the ecology of some conspicuous vertebrate species in south-west Western Australia" (PDF). Conservation Science W. Aust. 6 (3): 42–48.

- Menkhorst, P.W.; Knight, F. (2011). A field guide to the mammals of Australia (3rd ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. p. 106. ISBN 9780195573954.

- Claridge 2007, p. 3.

- Short, J.; Calaby, J. (July 2001). "The status of Australian mammals in 1922 - collections and field notes of museum collector Charles Hoy". Australian Zoologist. 31 (4): 533–562. doi:10.7882/az.2001.002. ISSN 0067-2238.

- Kennedy, Elicia (2019-09-22). "Numbats and woylies flourish at Dryandra after feral cats pushed WA icon towards 'extinction pit'". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- "Woylie (Bettongia penicillata)". Shark Bay World Heritage Area. Government of Western Australia - Department of Parks and Wildlife. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- Claridge 2007, pp. 82–83.

- Claridge 2007, p. 104.

- "Brush-tailed Bettong Woylie Bettongia penicillata" (PDF). Threatened species of the Northern Territory. Northern Territory Government - Department of Land Resource Management. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- Claridge 2007, pp. 116–117.

- Claridge 2007, p. 108.

- Berry, O.; Angus, J.; Hitchen, Y.; Lawson, J.; Macmahon, B.; Williams, A.A.E.; Thomas, N.D.; Marlow, N.J. (30 April 2015). "Cats (Felis catus) are more abundant and are the dominant predator of woylies (Bettongia penicillata) after sustained fox (Vulpes vulpes) control". Australian Journal of Zoology. 63 (1): 18–27. doi:10.1071/ZO14024. ISSN 1446-5698.

- Claridge 2007, p. 66.

- Claridge 2007, pp. 76–77.

- Claridge 2007, pp. 14–15.

- Short, J. (1998). "The extinction of rat-kangaroos (Marsupialia: Potoroidae) in New South Wales, Australia". Biological Conservation. 86 (3): 365–377. doi:10.1016/s0006-3207(98)00026-3.

- Claridge 2007, pp. 83–84.

- Leonie Harris (2008-10-07). "Woylie marsupial under threat". 7.30 report.

- "Bettongia penicillata ogilbyi - Woylie". Australian Government - Department of the Environment.

- Williams, M.R.; Wayne, J.C.; Wilson, I.; Vellios, C.V.; Ward, C.G.; Maxwell, M.A.; Wayne, A.F. (2013). "Sudden and rapid decline of the abundant marsupial Bettongia penicillata in Australia". Oryx. 49 (1): 175–185. doi:10.1017/S0030605313000677. ISSN 0030-6053.

- http://www.wildliferesearchmanagement.com.au/wadderin.html

- "Endangered Woylies increasing at Mt Gibson". AWC - Australian Wildlife Conservancy. 2020-07-02. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- "Woylie (Brush-tailed Bettong)". Shark Bay. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- Merrin, Venessa (2019-11-27). "Endangered Mala released into biggest feral predator-free area on mainland Australia". friendsofawc. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- "Mallee Cliffs National Park". AWC - Australian Wildlife Conservancy. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- "Benchmarking AWC's progress at two NSW National Parks". AWC - Australian Wildlife Conservancy. 2020-05-15. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- "Controversial wire fence splits peninsula to keep native animals in, pests out". www.abc.net.au. 2019-11-07. Retrieved 2020-09-03.