Xebec

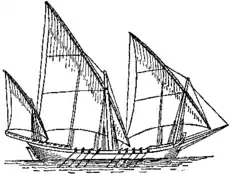

A xebec (/ˈziːbɛk/ or /zɪˈbɛk/), also spelled zebec, was a Mediterranean sailing ship that was used mostly for trading. Xebecs had a long overhanging bowsprit and aft-set mizzen mast. The term can also refer to a small, fast vessel of the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries, used almost exclusively in the Mediterranean Sea.

Description

Xebecs were ships similar to galleys primarily used by Barbary pirates, which have both lateen sails and oars for propulsion. Early xebecs had two masts; later ones three. Xebecs featured a distinctive hull with pronounced overhanging bow and stern,[1] and rarely displaced more than 200 tons, making them slightly smaller and with slightly fewer guns than frigates of the period.

Some victorious xebecs of the Spanish Navy, about 1770 (see Antonio Barceló campaigns... in the Spanish version of the page of Wikipedia):

- Andaluz, 30 guns (4 × 8-pounders)

- Africa, 18 guns (4-pounders)

- Atrevido, 20 guns

- Aventurero, 30 guns (3 × 8-pounders)

- Murciano, 16 guns, 4 pedreros (light swivel guns)

- San Antonio

Notable xebecs of the French Navy include four launched in 1750:

- Ruse, 160 tons, 18 guns

- Serpent, 160 tons burthen, 18 guns

- Requin, 260 tons burthen, 24 guns

- Indiscret, 260 tons burthen, 24 guns

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a large polacre-xebec carried a square rig on the foremast, lateen sails on the other masts, a bowsprit, and two headsails. The square sail distinguished this form of a xebec from that of a felucca which is equipped solely with lateen sails. The last of the xebecs in use by European navies were fully square-rigged and were termed xebec-frigates.

The British brig-sloop Speedy's (14 guns, 54 men) defeat of the Spanish xebec-frigate El Gamo (32 guns, 319 men) on 6 May 1801 is generally regarded as one of the most remarkable single-ship actions in naval history. It was the foundation of the legendary reputation of the Speedy's commander, Lord Cochrane, which has in turn provided the inspiration for sea fiction such as Patrick O'Brian's Master and Commander.[2]

Sea-going Mediterranean peoples greatly favoured xebecs as corsairs. The corsairs built their xebecs with a narrow floor to achieve a higher speed than their victims, but with a considerable beam in order to enable them to carry an extensive sail-plan. The lateen rig of the xebec allowed the ship to sail close hauled to the wind, something that often give it an advantage in pursuit or escape. The use of oars or sweeps allowed the xebec to approach vessels who were becalmed. When used as corsairs, the xebecs carried a crew of 300 to 400 men and mounted perhaps 16 to 40 guns according to size. In peacetime operations, the xebec could transport merchandise.

Etymology

Xebec is also written as xebeck, xebe(c)que, zebec(k), zebecque, chebec, shebeck (/ʃɪˈbɛk/); from (Catalan: xebec, French: chabec, now chebec, Spanish: xabeque, now jabeque, Portuguese: enxabeque, now xabeco, Italian: sciabecco, zambecco, stambecco, Maltese: xambekk, Greek: σεμπέκο, sebeco Ligurian: sciabécco, Arabic: شباك, šabbāk and Turkish: sunbeki). Words similar in form and meaning to xebec occur in Catalan, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Arabic and Turkish. The Online Etymology Dictionary regards the Arabic shabbak (meaning "a small warship") as the source form, however the Arabic root means 'a net', implying the word originally referred to a fishing boat.

The Spanish jabeque had only lateen sails, as portrayed in the Cazador. The Spanish Crown built Cazador in the mid-eighteenth century to fight Algerian corsairs (privateers) in the Mediterranean. Algerian corsairs also used three-lateen-sail xebecs in their raids on Mediterranean trade.

See also

References

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Xebecs. |

| Look up xebec in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Arabian chebec High-resolution photos of a model of an eighteenth-century xebec

- book "Chebec Le Requin 1750" with English Translation, by Jean Boudroit, 1991

- Definition of xebec source