Yehiel De-Nur

Yehiel De-Nur (Hebrew: יחיאל די-נור; De-Nur means 'of the fire' in Aramaic; also Romanized Dinoor, Di-Nur), also known by his pen name Ka-Tsetnik 135633, born Yehiel Feiner (16 May 1909 – 17 July 2001), was a Jewish writer and Holocaust survivor, whose books were inspired by his time as a prisoner in the Auschwitz concentration camp. His work, written in Hebrew, tends to "blur the line between fantasy and actual events" and consists of "often lurid novel-memoirs, works that shock the reader with grotesque scenes of torture, perverse sexuality, and cannibalism".[1]

Biography

Yehiel De-Nur was born in Sosnowiec, Poland. He was a yeshiva pupil in Lublin and later supported Zionism. In 1931 he published a book of Yiddish poetry which he tried to destroy after the war.[1]

During World War II De-Nur spent two years as a prisoner in Auschwitz. In 1945, he immigrated to Mandatory Palestine, (later the State of Israel). He wrote several works in Hebrew about his experiences in the camp using his identity number at Auschwitz: Ka-Tsetnik 135633 (sometimes "K. Tzetnik").

Ka-Tsetnik (ק. צטניק) is Yiddish for "Concentration Camper" (deriving from "ka tzet", the pronunciation of KZ, the abbreviation for Konzentrationslager); 135633 was De-Nur's concentration camp number. He also used the name Karl Zetinski (Karol Cetinsky, again the derivation from "KZ") as a refugee, hence the confusion over his real name when his works were first published.[2]

De-Nur was married to Nina De-Nur, the daughter of Prof. Yossef (Gustav) Asherman, a noted Tel Aviv gynecologist. She served in the British Army as a young woman. Nina sought him out after reading his book Salamandra and eventually they were married. She was instrumental in the translation and publication of many of his books. They had two children, a son (Lior) and a daughter (Daniella), named after his sister Daniella from "House of Dolls", both still living in Israel. She trained with Virginia Satir in the 1970s. Later in life, Nina changed her name to Eli-Yah De-Nur.

In 1976, because of recurring nightmares and depression, De-Nur subjected himself to a form of psychedelic psychotherapy promoted by Dutch psychiatrist Jan Bastiaans expressly for concentration camp survivors. The treatment included the use of the hallucinogen LSD, and the visions experienced during this therapy became the basis for his book, Shivitti.[3] The book's title is derived from David's Psalm 16:8, "Shiviti YHVH le-negdi tamid (שיויתי ה' לנגדי תמיד)," literally, "I have set YHVH before me always."

Yehiel De-nur died in Tel Aviv on 17 July 2001.

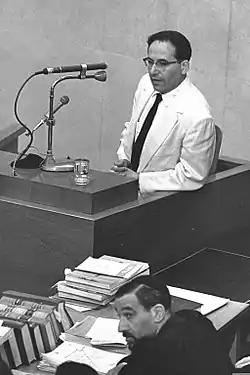

Testimony at Eichmann trial

His civic identity was revealed when he testified at the Eichmann Trial on 7 June 1961.[4] In his opening statement, Dinur presented a different opinion about the Holocaust than other well-known Holocaust writers (such as Elie Weisel), by presenting the Holocaust as a unique and out-this-world event, saying: "I do not see myself as a writer who writes literature. This is a chronicle from the planet Auschwitz. I was there for about two years. The time there is not the same as it is here, on Earth. (…) And the inhabitants of this planet had no names. They had no parents and no children. They did not wear [clothes] the way they wear here. They were not born there and did not give birth... They did not live according to the laws of the world here and did not die. Their name was the number K. Tzetnik."[5]

After saying so, De-Nur collapsed and gave no further testimony.

In an interview on 60 Minutes, aired 6 February 1983, De-Nur recounted the incident of his fainting at the Eichmann trial to host Mike Wallace.

Was Dinur overcome by hatred? Fear? Horrid memories? No; it was none of these. Rather, as Dinur explained to Wallace, all at once he realized Eichmann was not the god-like army officer who had sent so many to their deaths. This Eichmann was an ordinary man. "I was afraid about myself," said Dinur. "... I saw that I am capable to do this. I am ... exactly like he."[6]

In the book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil the author implies that his fainting might have been due to the response of prosecutor Gideon Hausner and presiding judge Moshe Landau, who thought he detracted from the case at hand with the spectacular witness statement of his.

Literary career

De-Nur wrote his first book about the Auschwitz experience, Salamandra, over two and a half weeks, while in a British army hospital in Italy in 1945. The original manuscript was in Yiddish, but it was published in 1946 in Hebrew in edited form.[1]

House of Dolls

Among his most famous works was 1955's The House of Dolls,[7] which described the "Joy Division", a Nazi system keeping Jewish women as sex slaves in concentration camps. He suggests that the subject of the book was his younger sister, who did not survive the Holocaust.

While De-Nur's books are still a part of the high-school curriculum, Na'ama Shik, a researcher at Yad Vashem, The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority in Israel, has claimed that The House of Dolls is pornographic fiction,[8] not least because sexual relations with Jews were strictly forbidden to all Aryan citizens of Nazi Germany.

In addition, professor Yechiel Szeintuch has suggested that De-Nur did not have a sister at all.[9]

The British rock band Joy Division derived its name from this book, which was quoted in their song "No Love Lost".

Its publication is at times pointed to as the inspiration behind the Nazi exploitation genre of serialized cheap paperbacks, known in Israel as Stalag fiction. Their publisher later acknowledged the Eichmann trial as the motive behind the series.

Lavie Tidhar's 2014 novel, A Man Lies Dreaming, engages with De-Nur's work and his writing. De-Nur appears briefly as a character, in a fictional conversation (in Auschwitz) with the author Primo Levi, whose subject is itself the question of how to write the Holocaust, and the novel concludes with a quote from Ka-Tzetnik on the nature of evil.

In De-Nur's 1961 book Piepel, about Nazi sexual abuse of young boys, he suggests the subject of this book was his younger brother, who also died in a concentration camp.[10]

Published works

- Salamandra, 1946; as Sunrise over Hell, translated by Nina Dinur, 1977

- Beit habubot, 1953; as House of Dolls, translated by Moshe M. Kohn, 1955

- Hashaon asher meal harosh (The Clock Overhead), 1960

- Karu lo pipl (They called Him Piepel), 1961; as Piepel, translated by Moshe M. Kohn, 1961; as Atrocity, 1963; as Moni: A Novel of Auschwitz, 1963

- Kokhav haefer (Star of Ashes), 1966; as Star Eternal, translated by Nina Dinur, 1972

- Kahol miefer (Phoenix From Ashes), 1966; as Phoenix Over The Galilee, translated by Nina Dinur, 1969; as House of Love, 1971

- Nidon lahayim (Judgement of Life), 1974

- Haimut (The Confrontation), 1975

- Ahavah balehavot, 1976; as Love in the Flames, translated by Nina Dinur, 1971

- Hadimah (The Tear), 1978

- Daniella, 1980

- Nakam (Revenge), 1981

- Hibutei ahavah (Struggling with Love), 1984

- Shivitti: A Vision, translated by Eliyah Nike Dinur and Lisa Herman, 1989

- Kaddish, (Contains Star Eternal plus essays written in English or Yiddish), 1998

- Ka-Tzetnik 135633 (Yehiel De-Nur), House of Dolls (London: Grafton Books, 1985)

- Ka-Tzetnik 135633 (Yehiel De-Nur), House of Love (London: W.H. Allen, 1971)

- Ka-Tzetnik 135633 (Yehiel De-Nur), Moni: A Novel of Auschwitz (New Jersey: Citadel Press, 1963)

- Ka-Tzetnik 135633 (Yehiel De-Nur), Phoenix Over The Galilee (New York: Harper & Row, 1969)

- Ka-Tzetnik 135633 (Yehiel De-Nur), Shivitti: A Vision (California: Gateways, 1998)

- Ka-Tzetnik 135633 (Yehiel De-Nur), Star Eternal (New York: Arbor House, 1971)

- Ka-Tzetnik 135633 (Yehiel De-Nur), Sunrise Over Hell (London: W.H. Allen, 1977)

References

- David Mikics (19 April 2012). "Holocaust Pulp Fiction". Tablet Magazine.

- archived, Tom Segev, Haaretz, 27 July 2001

- Maps.org

- The Trial of Adolf Eichmann, Session 68 (Part 1 of 9), Nizkor Project, 7 June 1961

- Translated to English by Tomer Golan, link to the trial testimony: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lw4kfrFgnRA

- Getz, Gene (2004). The Measure of a Man: Twenty Attributes of a Godly Man. Gospel Light Publications. p. 141. ISBN 0830734953.

- House of Dolls (Beit ha-bubot), novelguide.com, 2002

- Israel’s Unexpected Spinoff From a Holocaust Trial, Isabel Kershner, New York Times, 6 September 2007

- Yechiel Szeintuc (2009), Salamandra: myth and history in Katzetnik's writings, Carmel Jerusalem.

- sandrawilliams.org, Sandra S. Williams, Ka-tzetnik's use of paradox, 1993.

Further reading

- Anthony Rudolf, 'Ka-Tzetnik 135633,' in Sorrel Kerbel, Muriel Emanuel and Laura Phillips (eds.), Jewish Writers of the Twentieth Century (London: Routledge, 2003), p. 267

- "Holocaust History and the Readings of Ka-Tzetnik", Bloomsburry publishing, Annette F. Timm, 25 January 2018 (Associate Professor in the Department of History at the University of Calgary, Canada).

External links

- Project Nizkor: The Trial of Adolf Eichmann, Session 68, evidence of Yehiel Dinur

- Article in Haaretz

- Isaac Hershkowitz, Asmodeus and Nucleus on Planet Auschwitz: Katzetnik’s Theological and Demonological Kabbalah, a paper presented at the International Workshop: Ka-Tzetnik: The Impact of the First Holocaust Novelist in Israel and Beyond, University of Calgary, 10–12 March 2013.