ʻŌʻū

The ʻōʻū (pronounced [ˈʔoːʔuː][2]) (Psittirostra psittacea), is a species of Hawaiian honeycreeper, that is endemic to the Hawaiian islands. It has a dark green back and olive green underparts; males have a yellow head while females have a green head. Its unusual beak seems to be adapted to feeding on the fruits of Freycinetia arborea. It has a strong flight which it uses to fly considerable distances in search of this Hawaiian endemic vine, but will eat other fruits, buds, flowers and insects.

| ʻŌʻū | |

|---|---|

| |

| Keulemans illustration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Fringillidae |

| Subfamily: | Carduelinae |

| Genus: | Psittirostra Temminck, 1820 |

| Species: | P. psittacea |

| Binomial name | |

| Psittirostra psittacea (Gmelin, 1789) | |

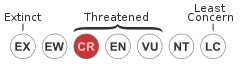

Although formerly widespread and present throughout the island group, numbers have declined dramatically during the twentieth century. It may have been affected by habitat loss and introduced predators, but the main factor in its decline is probably avian malaria and fowlpox, transmitted by the mosquito. The bird is listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as being critically endangered, but there are no recent records, and it may be extinct.

Description

The ʻōʻū is a large, plump forest bird measuring 17 centimetres (6.7 in) in length. Males have a bright yellow head, dark green back, and an olive-green belly. Females are duller with an olive-green head. The ʻōʻū has a pink, finch-like bill and pink legs.

Behavior

The breeding biology of this bird is unknown, although juveniles have been seen in June, suggesting a March to May breeding season. The ʻōʻū’s call is an ascending or descending whistle that may break into a sweet and distinct canary-like song.

Its unique bill was apparently adapted for feeding on the fruits of the ʻieʻie (Freycinetia arborea) vine, although when the fruiting season ended the ʻōʻū readily moved both up the slope and downslope in search of other foods, both native and introduced. In addition to fruits, it feeds on insects, and buds and blossoms of the ʻōhiʻa lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha). It was known to have been a nomadic forager that made strong flights to follow seasonally available fruit crops across a broad elevational gradient.

Status

Though it was formerly widespread on the six largest islands of that group, this Hawaiian honeycreeper declined precipitously from the turn of the 20th century. The last recorded sighting was in 1989 on Kauaʻi. It is almost certainly extinct there, but unconfirmed reports occasionally are received from the areas above the Kīlauea volcano on the island of Hawaiʻi. As a consequence, it is retained as critically endangered by BirdLife International (and thereby IUCN) until it is proven to be extinct beyond reasonable doubt. The largest and most secure population above Waiākea were driven from its habitat in 1984 when the area was devastated by a lava flow from Mauna Loa. The ʻōʻū was restricted to the mid-elevation ʻōhiʻa lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha) forests of the Big Island and the Alakaʻi Wilderness Preserve on Kauaʻi. More recently it became restricted to ʻōhiʻa lehua forest.

The ʻōʻū is one of the most mobile species of Hawaiian honeycreepers. Although it was not very active and usually slow-moving, it had remarkable stamina and when flying, would cover great distances. It is one of the few Hawaiian endemics that did occur on all the major islands at one time and did not differentiate into subspecies, suggesting that birds crossed between islands on a regular basis. Also, there was considerable seasonal movement between different altitudes according to the availability of the species' favorite food, the bracts and fruit of the ʻieʻie (Freycinetia arborea). This probably was the species' undoing, as it thus came in contact with mosquitoes transmitting avian malaria and fowlpox, which are exceptionally lethal to most Hawaiian honeycreepers. Other significant threats to this species are habitat loss and introduced predators. Island species are particularly vulnerable to one or more of these threats because of their low numbers and restricted geographical distributions.

Protection

The ʻōʻū was listed as an endangered species in 1967 under the Endangered Species Act. The Kauaʻi Forest Birds Recovery Plan was published in 1983 and the Hawaiʻi Forest Birds Recovery Plan was published in 1984. These recovery plans recommend active land management, controlling the spread of introduced plants and animals, closely monitoring new land activity or development to prevent further destruction of forest bird habitat, and the establishment of captive propagation and sperm bank programs. The ʻōʻū was last seen in the ʻOlaʻa area of the Big Island. Today this area is protected by a multiparty group including state, federal, and private entities.

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Psittirostra psittacea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pronunciation: Like "oh-oo". In contrast, the ʻoʻo ("oh-oh") is an unrelated Hawaiian bird (the ʻōʻō).