1876 Atlantic hurricane season

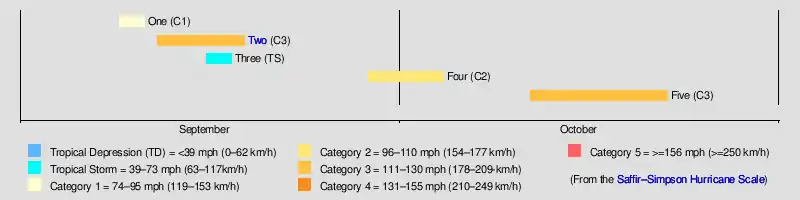

The 1876 Atlantic hurricane season lasted from mid-summer to late-fall. Records show that 1876 featured a relatively inactive hurricane season. There were five tropical storms, four became hurricanes, two of which became major hurricanes (Category 3+). However, due to the absence of remote-sensing satellite and other technology, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded; therefore, the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 has been estimated.[1] Of the known 1876 cyclones, both Hurricane One and Hurricane Four were first documented in 1995 by Jose Fernandez-Partagas and Henry Diaz. They also proposed large changes to the known tracks of Hurricane Two and of Hurricane Five.[2] The track and start position of Hurricane Five was further amended in 2003.[3]

| 1876 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | Before September 9, 1876 |

| Last system dissipated | October 23, 1876 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Five |

| • Maximum winds | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 958 mbar (hPa; 28.29 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total storms | 5 |

| Hurricanes | 4 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 19 |

| Total damage | Unknown |

Season summary

The Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT) officially recognizes five tropical cyclones for the 1876 season. Four storms attained hurricane status, with winds of 75 mph (119 km/h) or greater. The second and fourth hurricanes of the season were the most intense, with maximum sustained winds up to 120 mph (165 km/h). The first storm of the season was a hurricane that existed for two days in September off the east coast of the United States. Hurricane Two, known as the San Felipe hurricane, was the most notable storm of the season. It formed near the Windward Islands on September 12 and hit Puerto Rico as a Category 3 hurricane before crossing Hispaniola and Cuba. It continued northward to make landfall in North Carolina and continued through the interior of the United States as far as Cape Cod. It caused extensive damage in both Puerto Rico and North Carolina. The third cyclone of 1876 was a tropical storm, known to have existed for two days in the mid-Atlantic. The next cyclone, Hurricane Four, crossed from the Atlantic to the Pacific, passing over Nicaragua in late September and early October. The final storm of 1876 developed north of Panama and proceeded north across Cuba and Florida before dissipating on October 23.[4]

Timeline

Systems

Hurricane One

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 9 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) 970 mbar (hPa) |

A hurricane was discovered located roughly halfway between Bermuda and Nova Scotia on September 9. The hurricane did not strengthen and began to gradually weaken as it moved to the south of Newfoundland. It weakened to a tropical storm and later became extratropical on September 11.[4]

Hurricane Two

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 12 – September 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min) 980 mbar (hPa) |

Hurricane San Felipe of 1876

A hurricane first observed east of the Windward Islands on September 12 hit the islands that night. It strengthened to become a Category 3 hurricane, and hit between Yabucoa and Humacao, Puerto Rico, at that intensity on September 13. The storm made landfall in Puerto Rico and affected the island for over 10 hours with sustained winds of 100 mph. It then crossed over Hispaniola and Cuba before turning northward, avoiding Florida on the way. The weakened tropical storm headed towards the Carolinas, intensifying into a minimal hurricane before hitting near Wilmington, North Carolina, on September 17. The storm continued through the interior of the United States, dissipating on September 19 near Cape Cod.[4] In Puerto Rico, the lowest pressure was 29.20 inHg (989 mb) at San Juan and there were 19 deaths reported, but historians suspected the Spanish Government withheld the actual damage and death toll data for Puerto Rico.[5] At least two drownings occurred in Onslow County, North Carolina.[6] Flooding, damage to buildings, and uprooted trees were reported from Wilmington. A bridge across Market Street there was washed away.[7] In Puerto Rico the storm was remembered as the "San Felipe Hurricane" because it struck on September 13, the feast day of Saint Philip. Exactly 52 years later, Puerto Rico was struck by Hurricane San Felipe Segundo, a much more destructive and powerful cyclone.[5]

Tropical Storm Three

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 16 – September 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) |

The only tropical storm of the season was discovered on September 16 to the north-east of Antigua and Barbuda. It headed north, peaking at 60 mph (97 km/h) as it passed well to the east of Bermuda. It apparently dissipated on September 18.[4]

Hurricane Four

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 29 – October 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) |

A tropical storm was first observed on September 28 just to the east of the Leeward Islands. It later strengthened into a hurricane as it passed near the Netherlands Antilles. It later peaked as a Category 2 hurricane before making landfall in Nicaragua. The storm reached the Pacific Ocean before it dissipated on October 5.[4] The cyclone severely damaged parts of Central America, inundating the Nicaraguan capital of Managua with floodwaters. People climbed rooftops to evade the floodwaters. On the east coast of the country, 300 homes were destroyed at Bluefields. The ship Costa Rica, in the eastern Pacific and bound for Acapulco on October 4, lost her hurricane-deck as well as the head of her main mast, main topmast, and gaff. She also lost one of her quarter boats and experienced a wind shift at 2030 UTC.[8]

Hurricane Five

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 12 – October 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min) 958 mbar (hPa) |

The Cuba-South Florida Hurricane of 1876

A tropical storm was discovered north of Panama on October 12. It moved very slowly and generally northward. It became a hurricane early on October 17 and passed just east of Grand Cayman, where significant effects were reported.[9] It attained a peak intensity of 115 mph (185 km/h) just before making landfall on Bejucal in western Cuba, where the barometer dropped as low as 28.32 inches of mercury (959 mb) on October 19.[10] The calm center of the storm passed over the capital Havana and then entered the Straits of Florida.[2] Just before 00 UTC on October 20, the eye of the cyclone struck Key West, Florida, which reported atmospheric pressure of 28.73 inHg (973 mb) and wind of 11 mph (18 km/h) veering to the southwest.[2] About six hours later, early on October 20, the eye made landfall on the Florida mainland near Chokoloskee with winds of 105 mph (169 km/h). Emerging into the Atlantic near Sebastian around 12 UTC, it produced a pressure of 28.82 inHg (976 mb) at Cape Canaveral.[2] The cyclone later passed north of Bermuda before dissipating on October 23. Bermuda recorded gale-force winds and a pressure of 29.30 inHg (992 mb).[4]

On Grand Cayman, where west winds occurred during the closest approach of the cyclone, severe damage and the destruction of 170 houses was reported.[11] In South Florida, the hurricane produced tides of 8 feet (2.4 m) to 10 ft (3.0 m) on Biscayne Bay, but local ships rode out the storm in a natural anchorage called Hurricane Harbor, on the west side of Key Biscayne.[12] The bark Three Sisters was wrecked on Virginia Key, her cargo of lumber being salvaged by local residents.[12] The storm flooded the islands on Biscayne Bay and destroyed many structures.[13] On the Lake Worth Lagoon, the cyclone snapped or blew down large mastic and banyan trees, each more than 3 ft (0.9 m) in diameter and believed to have been hundreds of years old. All vegetation was stripped of foliage and branches were downed, while settlers' furniture was blown away. After the storm, the Atlantic Ocean appeared yellowish-brown due to silt, and numerous fish and sea mammals, including porpoises, were found beached.[14] The settlement that later became Palm Beach was destroyed.[15] Two decades later in 1896, the storm was still noted by settlers as among the worst ever in South Florida.[13] In passing over Eau Gallie near Melbourne, the calm eye lasted about four hours between 0830–1230 UTC.[16]

See also

References

- Landsea, C. W. (2004). "The Atlantic hurricane database re-analysis project: Documentation for the 1851–1910 alterations and additions to the HURDAT database". In Murname, R. J.; Liu, K.-B. (eds.). Hurricanes and Typhoons: Past, Present and Future. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 177–221. ISBN 0-231-12388-4.

- Partagás, José Fernández; H. F. Díaz (1995). "A reconstruction of historical tropical cyclone frequency in the Atlantic from documentary and other historical sources 1851 to 1880, Part II: 1871-1880". 1995b. Boulder, Colorado: Climate Diagnostics Center. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hurricane Research Division (2008). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- José Colón (1970). Pérez, Orlando (ed.). "Notes on the Tropical Cyclones of Puerto Rico, 1508–1970" (Pre-printed). National Weather Service: 26. Retrieved September 27, 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Barnes, Jay (1995). North Carolina's Hurricane History. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. p. 202.

- Hudgins,James E. (2000). "Tropical cyclones affecting North Carolina since 1586-An Historical Perspective" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- "MARINE DISASTERS" (PDF). New York Times. 28 October 1876. p. 10. Retrieved 2014-04-04.

- Gutiérrez-Lanza, M (1904). "Apuntes históricos acerca del Observatorio del Colegio de Belén". Havana, Cuba: Imprenta Avisador Comercial: 178. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Vines, Benito (1877). "Apuntes relativos a los huracanes de las Antillas en septiembre y octubre de 1875 y 76". Havana, Cuba: Tipografía El Iris: 256. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "none". The Times. London, U.K. November 13, 1876. p. 6.

- Woodman 1972, pp. 46–48; 25

- Munroe 1930, pp. 86–87

- Pierce 1970, pp. 83–85

- Kleinberg 2003, p. 24

- Duedall & Williams 2002, p. 9

Bibliography

- Duedall, Iver W.; Williams, John M. (2002), Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms, 1871-2001, University Press of Florida, ISBN 978-0813024943

- Kleinberg, Eliot (2003), Black Cloud: The Deadly Hurricane of 1928, Carroll and Graf, ISBN 0786711469

- Munroe, Ralph Middleton (1930), The Commodore's Story, Rumford Press, ASIN B00085QY84

- Oyer III, Harvey E. (2008), The American Jungle: The Adventures of Charlie Pierce, Middle River Press, ISBN 978-0981703602

- Pierce, Charles W. (1970), Donald W. Curl (ed.), Pioneer Life in Southeast Florida, University of Miami Press, ASIN B007T0707A

- Woodman, Jim (1972), Key Biscayne: The Romance of Cape Florida, ASIN B0006WVXQW