1926 Lithuanian coup d'état

The 1926 Lithuanian coup d'état (Lithuanian: 1926-ųjų perversmas) was a military coup d'état in Lithuania that resulted in the replacement of the democratically elected government with a conservative authoritarian government led by Antanas Smetona. The coup took place on 17 December 1926 and was largely organized by the military; Smetona's role remains the subject of debate. The coup brought the Lithuanian Nationalist Union, the most conservative party at the time, to power.[1] Before 1926, it had been a fairly new and insignificant nationalistic party: in 1926, its membership numbered about 2,000 and it had won only three seats in the parliamentary elections.[2] The Lithuanian Christian Democratic Party, the largest party in the Seimas at the time, collaborated with the military and provided constitutional legitimacy to the coup, but did not accept any major posts in the new government and withdrew in May 1927. After the military handed power over to the civilian government, it ceased playing a direct role in political life.

Background

Lithuania was incorporated into the Russian Empire in 1795. It was occupied by Germany during World War I, and declared itself independent on 16 February 1918. The next two years were marked by the turbulence of the Lithuanian Wars of Independence, delaying international recognition and the establishment of political institutions. The newly formed army fought the Bolsheviks, the Bermontians, and Poland. In October 1920, Poland annexed Vilnius, the historic and modern-day capital of Lithuania, and the surrounding area; this controversial action was the source of ongoing tension between the two powers during the interwar period. Lithuania's second-largest city, Kaunas, was designated the interim capital of the state.

The Constituent Assembly of Lithuania, elected in April 1920, adopted a constitution in August 1922; elections to the First Seimas took place in October 1922. The most-disputed constitutional issue was the role of the presidency. Eventually, the powers of government were heavily weighted in favor of the unicameral parliament (Seimas). Members of the Seimas were elected by the people to three-year terms. Each new Seimas directly elected the president, who was authorized to appoint a prime minister. The Prime Minister was then charged with confirming a cabinet of ministers. The presidential term was limited to no more than two three-year terms in succession.[3] The parliamentary system proved unstable: eleven cabinets were formed between November 1918 and December 1926.[4]

The principal political actors at the time of the coup had been active during the independence movement and the republic's first few years. Antanas Smetona had served as Lithuania's first president between April 1919 and June 1920; he then withdrew from formal political involvement, although he published political criticism, for which he served a brief prison term in 1923.[5] Augustinas Voldemaras represented Lithuania at the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in 1918 and later served as Prime Minister, Minister of Defense, and Minister of Foreign Affairs. He resigned from the government in 1920, although he continued to write and publish political criticism, for which he also was sentenced to a short prison term.[6] Kazys Grinius had chaired a post-World War I repatriation commission, and went on to serve as head of the 6th Cabinet of Ministers and in the First and Second Seimas.[7] Mykolas Sleževičius served as prime minister in 1918 and 1919, oversaw the organization of the Lithuanian armed forces in 1920, and was a member of the Second Seimas between 1922 and 1926.[8]

1926 parliamentary election

| Results of the 1926 parliamentary election[9] | |

|---|---|

| Party | Seats |

| Christian Democratic Bloc (krikdemai) | 30 |

| Peasant Popular Union (liaudininkai) | 22 |

| Social Democrats (socdemai) | 15 |

| National Union (tautininkai) | 3 |

| Farmers' Party | 2 |

| Minorities (Germans, Jews, and Poles) | 13 |

| Total | 85 |

Between 8 and 10 May 1926, regular elections to the Third Seimas were held. For the first time since 1920, the bloc led by the Lithuanian Christian Democratic Party, which strongly supported the Roman Catholic Church and its clergy, did not obtain a majority. The Lithuanian people were disillusioned with this party, as its members had been involved in several financial scandals: Juozas Purickas had been using his diplomatic privileges in Moscow to deal in cocaine and saccharin; Eliziejus Draugelis and Petras Josiukas had purchased cheap low-quality smoked pig fat from Germany instead of buying from Lithuanian farmers; and the Minister of Finance, Vytautas Petrulis, had transferred a large sum of money from the state budget to his personal account.[10] The party's strategies for coping with an economic crisis were perceived as ineffective.[11]

An additional tension arose when the Concordat of 1925 between Poland and the Holy See unilaterally recognized Vilnius as an ecclesiastical province of Poland, despite Lithuanian requests to govern Vilnius directly from Rome. Although it was not traditionally a Vatican policy to establish an arrangement of this type, the decision was objected to strongly by many Lithuanians.[12] The decision implied that the Pope had recognized Polish claims to Vilnius, and this created a loss of prestige for the Christian Democrats.[4] Diplomatic relations with the Holy See were severed,[12] and they did not improve when Pope Pius XI unilaterally established and reorganized Lithuanian ecclesiastical provinces in April 1926 without regard to Lithuanian proposals and demands.[13]

The Peasant Popular Union and Social Democrats formed a left-wing coalition in opposition to the Christian Democrats. But the coalition still did not constitute a majority, and it went on to add representatives of minorities in Lithuania – Germans from the Klaipėda Region, Poles, and Jews.[1] On 7 June, Kazys Grinius was elected the 3rd president of Lithuania and Mykolas Sleževičius became the prime minister. Both were members of the Peasant Popular Union.

Causes

The reasons for the coup remain the subject of debate.[1] The domestic situation was definitely troubled; historians have pointed to specific European precedents in the 1920s that may have had an influence, including the 1922 March on Rome by Benito Mussolini in Italy and the May 1926 Coup of Józef Piłsudski in Poland.[14] Other historians have cited more general trends in Europe that resulted in more or less undemocratic governments in almost all Central and Eastern European nations by the end of the 1930s. Democratic immaturity was displayed by an unwillingness to compromise, and the frequent shifts of government created a chronic perception of crisis. Historians have also discussed an exaggerated fear of communism[1] as a factor, along with the lack of a stable center that could reach out to parties on the left and right; these parties accused each other of Bolshevism and fascism.[14] According to historian Anatol Lieven, Smetona and Voldemaras saw themselves as the dispossessed true heroes of the independence movement, who despaired of returning to power by democratic means.[15]

After the May elections, the Grinius/Sleževičius government lifted martial law, still in effect in Kaunas and other localities, restored democratic freedoms, and granted broad amnesty to political prisoners. For the first time, Lithuania had become truly democratic.[11] However, the change did not meet with universal approval. Many of the released prisoners were communists who quickly used the new freedoms of speech to organize a protest attended by approximately 400 people in Kaunas on 13 June. The protest was dispersed.[10] The new government's opposition used this protest as the platform for a public attack on the government, alleging that it was allowing illegal organizations (the Communist Party of Lithuania was still outlawed) to continue their activities freely. Despite its local nature, the incident was presented as a major threat to Lithuania and its military; the government was said to be incapable of dealing with this threat.[10]

Further allegations of "Bolshevization" were made after Lithuania signed the Soviet–Lithuanian Non-Aggression Treaty of 28 September 1926. The treaty was conceived by the previous government, which had been dominated by the Christian Democrats. However, Christian Democrats voted against the treaty, while Antanas Smetona strongly supported it. It drew sharp criticism as Lithuania exchanged Soviet recognition of its rights to the Vilnius Region for international isolation, as the treaty demanded that Lithuania make no other alliances with other countries.[14] At the time, the Soviet Union was not a member of the League of Nations; France and the United Kingdom were looking for reliable partners in Eastern Europe,[14] and the Baltic states were contemplating a union on their own.[16] On 21 November, a student demonstration against "Bolshevization" was forcibly dispersed by the police.[14] About 600 Lithuanian students gathered near a communist-led workers' union. The police, fearing armed clashes between the two groups, intervened and attempted to stop the demonstration. Seven police officers were injured and thirteen students were arrested.[10] In an attempt to overthrow the government legally, the Christian Democrats suggested a motion of no confidence in response to the incident, but it was rejected.[11]

Another public outcry arose when the government, seeking the support of ethnic minorities, allowed the opening of over 80 Polish schools in Lithuania. At the time, the Polish government was closing Lithuanian schools in the fiercely contested Vilnius Region.[12] The coalition government directly confronted the Christian Democrats when it proposed a 1927 budget that reduced salaries to the clergy and subsidies to Catholic schools. Further controversies were created when the government's military reform program was revealed as a careless downsizing.[16] Some 200 conservative military officers were fired.[14] The military began planning the coup.

Preparations

There is considerable academic debate concerning the involvement of Antanas Smetona in planning the coup. In 1931, Augustinas Voldemaras, who had since been ousted from the government and forced into exile, wrote that Smetona had been planning the coup since 1925.[10] Historian Zenonas Butkus asserted that an idea of a coup had been raised as early as 1923.[11] However, this time frame is disputed, since the military did not take action until the autumn of 1926. Smetona's personal secretary, Aleksandras Merkelis, held that Smetona knew about the coup, but neither inspired nor organized it.[17] Before the coup, Smetona had been the editor of Lietuvis (The Lithuanian), and a shift in its orientation that took place in late November has been cited as evidence that he was not informed about the coup until then. Before the issue of 25 November appeared, the newspaper was critical of the government and of the Christian Democrats. On that date, however, the newspaper published several articles about 21 November student protest and an article headlined Bolshevism's Threat to Lithuania. The latter article argued that the communists posed a genuine threat and that the current government was incapable of dealing with it. After that date, the newspaper ceased issuing criticisms of the Christian Democrats.[17]

On 20 September 1926, five military officers, led by Captain Antanas Mačiuika, organized a committee. Generals Vladas Nagevičius and Jonas Bulota were among its members. About a month later, another group, the so-called Revolutionary General Headquarters (Lithuanian: revoliucinis generalinis štabas), was formed. The two groups closely coordinated their efforts.[11] By 12 December, the military had already planned detailed actions, investigated the areas where the action was to take place, and informed the leaders of the Lithuanian National Union and Christian Democratic parties. Rumors of the plan reached the Social Democrats, but they took no action.[11] Just before the coup, disinformation about movements of the Polish army in the Vilnius Region was disseminated; its purpose was to induce troops in Kaunas that would potentially have opposed the coup to move towards Vilnius.[10]

The coup

Late in the evening of 16 December, the Soviet consul informed Sleževičius about a possible coup the following night, but Sleževičius did not pay much attention to this warning.[18] The coup began on the night of 17 December 1926. The 60th birthday of President Kazys Grinius was being celebrated in Kaunas, attended by numerous state officials. The 1927 budget, with its cuts to military and church spending, had not yet been passed. During the night, military forces occupied central military and government offices and arrested officials. Colonel Kazys Škirpa, who had initiated the military reform program,[12] tried to rally troops against the coup, but was soon overpowered and arrested.[16] The Seimas was dispersed and President Grinius was placed under house arrest. Colonel Povilas Plechavičius was released from prison (he had been serving a 20-day sentence for a fist fight with another officer) and declared dictator of Lithuania.[11] Later that day, Colonel Plechavičius asked Smetona to become the new President and normalize the situation. The military strove to create the impression that the coup had been solely their initiative, that Smetona had not been involved at all, and that he had joined it only in response to an invitation to serve as the "savior of the nation".[11] Prime Minister Sleževičius resigned, and President Grinius appointed Augustinas Voldemaras as the new Prime Minister.

Smetona and Voldemaras, both representing the Lithuanian National Union, invited the Christian Democrats to join them in forming a new government that would restore some degree of constitutional legitimacy. The party agreed reluctantly; they were worried about their prestige. Looking toward the near future, the Christian Democrats reasoned that they could easily win any upcoming Seimas elections, regaining power by constitutional means and avoiding direct association with the coup.[14] In keeping with this strategy, they allowed members of the Lithuanian National Union to take over the most prominent posts.

Initially, President Grinius refused to resign, but he was eventually persuaded that Polish invasion was imminent and that Smetona had sworn to uphold the constitution.[14] On 19 December 42 delegates of the Seimas met (without the Social Democrats or the Peasant Popular Union) and elected Aleksandras Stulginskis as the new Speaker of the Seimas. Stulginskis was the formal head of state for a few hours before Smetona was elected as the President (38 deputies voted for, two against, and two abstained).[14] The Seimas also passed a vote of confidence in the new cabinet formed by Voldemaras. Constitutional formalities were observed thereby.[12] The Lithuanian National Union secured other major roles: Antanas Merkys assumed office as Minister of Defense and Ignas Musteikis as Minister of the Interior.[14]

Aftermath

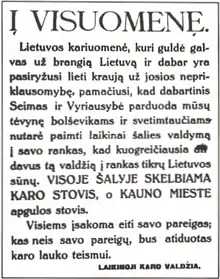

The official rationale given by the military was that their actions had prevented an imminent Bolshevik coup, allegedly scheduled for 20 December. Martial law was declared. About 350 communists were arrested and four leaders (Karolis Požela, Juozas Greifenbergeris, Kazys Giedrys and Rapolas Čarnas) were executed on 27 December.[11] This was a serious blow to the Communist Party of Lithuania and it was inactive for a time.[16] No concrete evidence was ever found that the communists had planned any coups.[11] Other political parties and organizations were not brutalized and, according to the military, no casualties were associated with the coup, apart from the four executions.[12] However, other sources cite the case of Captain Vincas Jonuška, who was allegedly shot by the guards of the Presidential Palace, and died a day later in a hospital.[19]

International recognition of the new government did not prove to be difficult.[14] The Western powers were not pleased with the Third Seimas when it ratified the non-aggression treaty with the Soviet Union in September. They were looking for a government that would change the priorities of Lithuanian foreign policy. It was therefore not surprising that the British The Daily Telegraph, the French Le Matin, and the United States' The New York Times wrote that the coup was expected to curtail the move towards friendly relations with the Soviet Union and normalize relations with Poland; the anti-democratic and unconstitutional nature of the coup was not emphasized.[20] The Western press reported the news calmly, or assessed it as a positive development in the Lithuanian struggle against Bolshevism. International diplomatic opinion held that a strong authoritarian leader would provide internal stability, and that even during the earlier years of the republic Lithuania had not been genuinely democratic, since many essential freedoms were curtailed under martial law.[20]

The Christian Democrats, believing that the coup was merely a temporary measure, demanded that new elections to the Seimas be held, but Smetona stalled. He predicted that his party would not be popular and that he would not be re-elected president.[21] In the meantime, the Nationalists were discussing constitutional changes that would increase the powers of the executive branch while curbing the powers of the Seimas.[12] In April, a group of populists tried to organize a coup "to defend the constitution," but the plans were discovered and the rebels were arrested. Among the detainees was a member of the Seimas, Juozas Pajaujis. On 12 April 1927, the Seimas protested this arrest as a violation of the parliamentary immunity by delivering a motion of no confidence against the Voldemaras government.[22] Smetona, using his constitutional right to do so, dissolved the Seimas. The constitution was violated, however, when no new elections were held within two months.[17] In April, Christian Democratic newspapers, which had been calling for new elections, were censored. On 2 May 1927, Christian Democrats withdrew from the government, thinking that the Nationalists acting alone would not be able to sustain it.[22] As a result, the Lithuanian National Union took the upper hand in its dispute with a much larger and influential rival and assumed the absolute control of the state.

The 1926 coup was a major event in interwar Lithuania; the dictatorship would go on for 14 years. In 1935, the Smetona government outlawed the activities of all other political parties.[4] The coup continues to be a difficult issue for Lithuanians, since the Soviet Union would go on to describe its subsequent occupation of Lithuania as a liberation from fascism. Encyclopædia Britannica, however, describes the regime as authoritarian and nationalistic rather than fascist.[23] The coup's apologists have described it as a corrective to an extreme form of parliamentarianism, justifiable in light of Lithuania's political immaturity.[24]

References

- Vardys, Vytas Stanley; Judith B. Sedaitis (1997). Lithuania: The Rebel Nation. Westview Series on the Post-Soviet Republics. WestviewPress. pp. 34–36. ISBN 0-8133-1839-4.

- Kamuntavičius, Rūstis; Vaida Kamuntavičienė; Remigijus Civinskas; Kastytis Antanaitis (2001). Lietuvos istorija 11–12 klasėms (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Vaga. p. 385. ISBN 5-415-01502-7.

- Laučka, Juozas B. (Fall 1986). "The Structure And Operation Of Lithuania's Parliamentary Democracy 1920–1939". Lituanus. 32 (3). ISSN 0024-5089. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- Crampton, R. J. (1994). Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century. Routledge. p. 102. ISBN 0-415-05346-3. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- "Antanas Smetona". Institution of the President of the Republic of Lithuania. Archived from the original on 30 March 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- Vaičikonis, Kristina (Fall 1984). "Augustinas Voldemaras". Lituanus. 30 (3). ISSN 0024-5089. Retrieved 10 March 2008.

- "Kazys Grinius". Institution of the President of the Republic of Lithuania. Archived from the original on 30 March 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- "Mykolas Sleževičius" (in Lithuanian). Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- Eidintas, Alfonsas (1991). Lietuvos Respublikos prezidentai (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Šviesa. p. 104. ISBN 5-430-01059-6.

- Eidintas, Alfonsas (1991). Lietuvos Respublikos prezidentai (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Šviesa. pp. 87–95. ISBN 5-430-01059-6.

- Kulikauskas, Gediminas (2002). "1926 m. valstybės perversmas". Gimtoji istorija. Nuo 7 iki 12 klasės (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Elektroninės leidybos namai. ISBN 9986-9216-9-4. Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- Gerutis, Albertas (1984). "Independent Lithuania". In Albertas Gerutis (ed.). Lithuania: 700 Years. Translated by Algirdas Budreckis (6th ed.). New York: Manyland Books. pp. 216–221. ISBN 0-87141-028-1. LCC 75-80057.

- Eidintas, Alfonsas (1991). Lietuvos Respublikos prezidentai (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Šviesa. pp. 50–51. ISBN 5-430-01059-6.

- Eidintas, Alfonsas; Vytautas Žalys; Alfred Erich Senn (September 1999). Ed. Edvardas Tuskenis (ed.). Lithuania in European Politics: The Years of the First Republic, 1918–1940 (Paperback ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 53–58. ISBN 0-312-22458-3.

- Lieven, Anatol (1994). The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and the Path to Independence. Yale University Press. p. 66. ISBN 0-300-06078-5. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- Kamuntavičius, Rūstis; Vaida Kamuntavičienė; Remigijus Civinskas; Kastytis Antanaitis (2001). Lietuvos istorija 11–12 klasėms (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Vaga. pp. 376–379. ISBN 5-415-01502-7.

- Antanas Drilinga, ed. (1995). Lietuvos Respublikos prezidentai (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Valstybės leidybos centras. pp. 86–90. ISBN 9986-09-055-5.

- Žalys, Vytautas (2006). Lietuvos diplomatijos istorija (1925–1940). T-1. Vilnius: Versus aureus. p. 210. ISBN 9955-699-50-7.

- Antanas Drilinga, ed. (1995). Lietuvos Respublikos prezidentai (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Valstybės leidybos centras. pp. 330–331. ISBN 9986-09-055-5.

- Kasperavičius, Algimantas (2006). "The Historical Experience of the Twentieth Century: Authoritarianism and Totalitarianism in Lithuania". In Jerzy W. Borejsza; Klaus Ziemer (eds.). Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes in Europe: Legacies And Lessons. Berghahn Books. pp. 299–300. ISBN 1-57181-641-0. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- Eidintas, Alfonsas; Vytautas Žalys; Alfred Erich Senn (September 1999). Ed. Edvardas Tuskenis (ed.). Lithuania in European Politics: The Years of the First Republic, 1918–1940 (Paperback ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 112. ISBN 0-312-22458-3.

- Eidintas, Alfonsas (1991). Lietuvos Respublikos prezidentai (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Šviesa. pp. 107–108. ISBN 5-430-01059-6.

- "Baltic states:Independence and the 20th century > Independent statehood > Politics". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2008.

- Lane, Thomas (2001). Lithuania: Stepping Westward. Routledge. pp. 23–24. ISBN 0-415-26731-5. Retrieved 19 June 2010.