1926 Passaic textile strike

The 1926 Passaic textile strike was a work stoppage by over 15,000 woolen mill workers in and around Passaic, New Jersey, over wage issues in several factories in the vicinity. Conducted in its initial phase by a "United Front Committee" organized by the Trade Union Educational League of the Workers (Communist) Party, the strike began on January 25, 1926, and officially ended only on March 1, 1927, when the final mill being picketed signed a contract with the striking workers. It was the first Communist-led work stoppage in the United States. The event was memorialized by a seven reel silent movie intended to generate sympathy and funds for the striking workers.

| 1926 Passaic textile strike | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Passaic strikers and their children picketing outside the White House in Washington, DC. | |||

| Date | January 25, 1926 - March 1, 1927 | ||

| Location | |||

| Goals | Eight-hour work day, wages | ||

| Methods | Strikes, Protest, Demonstrations | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| |||

History

Prelude to the strike

From the end of the 19th Century, Passaic, New Jersey, located just south of the city of Paterson, was the heart of an industrial district which included the towns of Lodi, Wallington, Garfield, and the city of Clifton.[1] While cotton and woolen mills had been constructed in the area as early as the 1860s, it was not until 1889, when Congress increased the rate of tariffs on imported worsted wool that the textile industry expanded in any meaningful way.[1]

In the middle part of the 1920s, there were over 16,000 workers employed in the wool and silk mills located in and around Passaic, New Jersey.[2] The largest of the mills in the area, the German-owned Botany Worsted Mill, employed 6,400 workers, with three other giant mills employing thousands more.[2] The workers at these facilities were predominantly foreign-born, including among them representatives of 39 nationalities, with immigrants from Poland, Italy, Russia, Hungary in particular evidence.[2] Fully half the workforce was female.[2]

Wages of these workers were miserable. A 1926 survey indicated that male workers in the Passaic textile mills averaged wages of from $1,000 to $1,200 per year, while female workers typically earned from $800 to $1,000 per annum.[2] Female workers worked 10 hours a day to earn this sum, with the pace of work rapid and the use of the piecework system prevalent.[2] With an income of approximately $1,400 estimated to be necessary to maintain a basic "American standard of living," many New Jersey factory workers found themselves on the brink of financial disaster.[3]

This was not just a question of creature comforts for many Passaic textile workers, but a matter of life and death. The 1925 report of the New Jersey Department of Health showed a death rate for infants under 1 year of age that was 43% higher than for the rest of the state, 52% higher for children aged 1–5 and 5-9.[4] Sanitary conditions were poor and an exhaustingly long work week in poorly ventilated facilities resulted in a higher than average rate of tuberculosis[4] as well as other diseases.

The affected workers had little recourse to their situation. Despite previous efforts to organize the Passaic millworkers by the Industrial Workers of the World and the Workers International Industrial Union in 1912 and the Amalgamated Textile Workers Union in 1919 and 1920, as of 1925 there were no textile unions extant in the area.[5] A conscious effort was made by the mill owners to employ as many different nationalities as possible in their facilities, thereby making the task of labor organization even more difficult.[6]

A majority of the strikers were foreign-born, with the biggest percentage being Poles, followed by Italians and Hungarians.[7] Despite the divergent nationalities involved, it was judged that, given the limits placed upon new immigration, these foreign-born workers had been more tightly attached to their occupations and "greatly Americanized." Communist union organizer Ben Gitlow observed that these workers "understand English and have acclimated themselves to many of the American customs," cemented together by their American-born children into "one homogeneous whole."[7]

In the fall of 1925, after first applying economic pressure to household budgets by the cutting of work hours, Passaic's largest mill, Botany, implemented a 10% wage cut.[8] This cut was matched at once by all the other mills in the area, save one.[8]

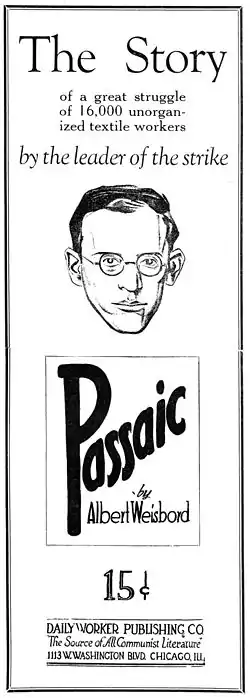

A former Phi Beta Kappa graduate of City College of New York and Harvard Law School, Albert Weisbord, was already active in the Passaic area as an organizer for the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), the trade union arm of the Workers (Communist) Party.[8] Weisbord moved into the void, establishing a "United Front Committee of Textile Workers" (UFC) — a de facto union organizing committee for the supposedly "unorganizable" immigrant mill hands. Within about 2 months, the UFC had enrolled about 1,000 workers in its ranks to fight the wage cut at the Botany Worsted Mill.[9]

Outbreak of the strike

On January 21, 1926, a worker speaking out for the United Front Committee was fired from the Botany Worsted Mills for his organizing activity, sparking worker unrest.[10] A committee of 3 was elected by the members of the UFC to meet with the manager of the Botany facility to discuss the firing. This committee was told in no uncertain terms that any individuals known to be members of the UFC would be similarly terminated, a hardline position which further inflamed the situation.[10]

Another meeting of the UFC followed on January 25, at which it was decided to elect a committee of 45 to meet again with management.[10] This time not in supplication for the reinstatement of a fired colleague, but rather to present a set of concrete demands, including establishment of a 44-hour work week,[11] elimination of the 10% pay cut effected in October 1925, initiation of the payment of time-and-a-half rates for overtime work, and firm promises that there would be no retaliation by management against union members.[10] Instead of negotiating, the manager of the mill chose to fire the entire committee on the spot. The committee returned to their places at the mill, told their fellow workers what had transpired, and called for them to shut down production. Within an hour, 4,000 Botany workers had walked out and begun to picket at the factory gate, and the strike was on.[10]

The strike develops

On February 9, 1926, a line of strikers attempted to cross the bridge from Passaic to the neighboring Clifton in an attempt to shut down the Forstmann & Huffman mill in that city.[12] They were met at the bridge by a line of police, who wielded their clubs and turned back the strikers.[12] The effort was repeated the next day and a picket line was established and joined by many workers of the mill.[12] In the face of continued aggressive picketing, the firm was forced to shutter its operations for the duration of the strike on February 23.[12]

The authorities met this expansion of the strike with intensified force. On February 25, the Passaic City Council invoked a Riot Act which had been on the books for more than six decades against the strikers.[13] On March 2, a line of policemen blockaded a street along which a line of pickets was passing. Stopped in their tracks, the police began clubbing the massed strikers and dispersed the crowd with the use of tear gas and firehoses of icy-cold water.[13] Horses and motorcycles were ridden into the crowd.[11][14] The riotous scene was repeated the next day, this time with newspaper reporters and photographers present to chronicle the mayhem.[13] The authorities took the fight to the press, clubbing cameramen and destroying cameras.[14] Dozens were arrested, including strike leader Albert Weisbord, who was held on $50,000 bail.[11]

The strikers paused for a day before making their next effort, this time donning steel helmets and passing triumphantly through the police line as cameramen documented the scene from the safe confines of armored cars and via an airplane overhead.[13][14]

The strikers next turned their attention to the United Piece Dye Works of Lodi, located three miles from Passaic. This large factory was also shut down under the pressure of picketing workers on March 9.[12] The original strike of 4,000 Botany workers had grown to 15,000 of the estimated 17,000 textile workers in the area.[12]

Mass meetings of the strikers were held daily and picket lines continued without interruption.[15] A governing strike committee containing representatives from each striking mill, as well as delegates from participating ethnic groups, met each morning at 9 am. Key organizers were provided by the Workers (Communist) Party and included, in addition to Albert Weisbord, New York, garment worker Lena Chernenko and Jack Stachel of the Trade Union Educational League.[15]

Borrowing a page from the successful 1912 Lawrence Textile Strike by sending away children of striking workers to the homes of sympathizers in New York City.[16] This simultaneously reduced the maintenance cost of the strike and served as a vehicle to garner publicity and support for the work stoppage.

A more innovative attempt to garner public sympathy and financial support came in the form of a motion picture shot to aid the strikers' cause. Entitled simply The Passaic Textile Strike, the 7-reel film was directed by Samuel Russak and produced by Communist Party functionary Alfred Wagenknecht, making use of funds provided by International Workers Aid, an adjunct of the Communist International.[17]

In April Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas and Communist Robert W. Dunn, members of the National Committee of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), challenged the virtual imposition of martial law by Bergen County's sheriff, by speaking to strikers there.[14] Thomas and Dunn were arrested with two others for violation of the New Jersey "Riot Act" and held under $10,000 bond, providing an opportunity for the ACLU to begin legal action and to obtain an injunction against the sheriff for his alleged violation of civil rights.[18] The courage of Thomas, Dunn, and their fellows was followed by others, including Reverend John Haynes Holmes and constitutional scholar Arthur Garfield Hays, who likewise came to Passaic in defiance of the authorities to exercise their constitutional rights.[18]

Strike support

Acting in support of the strikers, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn of the so-called "Garland Fund" hired Mary Heaton Vorse to act as publicity director for the strike.[12] Vorse produced a regular Textile Strike Bulletin to keep strikers and sympathetic outsiders abreast of developments in the ongoing work stoppage.[12] This publication was instrumental in helping to raise funds on behalf of the relief effort.

The strikers were supported through the establishment of four relief stores and two soup kitchens, operated by the strikers and their sympathizers with Alfred Wagenknecht in charge of the operation.[11] Local bakers supplied bread, shoemakers repaired footwear of strikers without charge, barbers donated shaves and haircuts, and other unions, such as the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union contributed a wide array of foodstuffs.[11] A playground was constructed for the children of strikers, some of whom were also sent off to summer camps.[11] The strikers' General Relief Committee tried to raise funds by issuing and selling a heavily illustrated, poignant photographic survey of the strike entitled "Hell in New Jersey."

The American Federation of Labor takes over

Despite the series of successful strike actions and public relations victories, the Passaic labor stoppage dragged on interminably, with no end in sight. As early as March 28, 1926, strike leader Albert Weisbord had appealed to the American Federation of Labor's Executive Council for help.[19] This appeal was rejected summarily by William Green of the AF of L, who declared that his organization would have nothing to do with any "Communist-dominated United Front Committee."[19]

Locked in a stalemate with management with no end in sight, the Communists were uncertain how to proceed. After a period of debate, the Communists and the leadership of their TUEL adjunct made the determination that "it would be incorrect to let the issue of communism stand in the way of a settlement," even though this position would mean that Weisbord and the rest of the party's leadership would as a result be removed to pave the way for an agreement.[20] On August 12, 1926, a committee elected by the strikers met with officials of the AF of L-affiliated United Textile Workers of America and reached agreement that the union should take over the strike, replacing Weisbord and the United Front Committee.[20] The Passaic strikers were accepted as Local 1603 of the UTW.[11]

After the transition from the Communist-led United Front Committee to the United Textile Workers in September, relief funds for the strikers began to dry up and morale started to drop.[21] The strike continued to wind along into the fall, however, with the UTW entering into direct negotiations with factory management.

The first break in the Passaic strike came on November 12, 1926, when the Passaic Worsted Company signed an agreement with the union.[22] On December 12, Botany Mills and its subsidiary, Garfield Worsted Mills, settled with the strikers.[11] A series of negotiated settlements followed, with the final mill settling coming on March 1, 1927.[21]

And so the great battle came to a close.

Aftermath and legacy

The relationship between the United Textile Workers and their Passaic local remained an uneasy one. The Communists charged that an agreement was made between the International office of the United Textile Workers of America and Botany Mills agreeing that "the active and militant workers, and all those that may look 'Red,' must not go back into the mills."[23] The situation was further muddied by an economic downturn in the textile industry which left many of the former strikers unemployed.[11] Of those rehired, it was alleged that many were promptly laid off and then rehired into another department at a lower rate of pay.[24]

This simmering acrimony between the union's headquarters and its active members in New Jersey finally erupted in 1928, when the UTW expelled the entire Passaic local for its support of the ongoing Communist-led strike of textile workers in New Bedford, Massachusetts.[21]

The Passaic Textile Strike of 1926 is remembered as one of the seminal events in American labor history in the decade of the 1920s. The historical memory of the event has been enhanced due to its immortalization in film. Five of the seven reels of the film The Passaic Textile Strike have survived, with reels 5 and 7 missing.[25] In 2006, graduate students in New York University's Moving Image Archiving and Preservation program discovered the missing reel 5 while processing films belonging to the Communist Party USA's collection.[26] Reel 5 was subsequently meticulously reprinted and preserved by Colorlab and the Library of Congress.[27]

Facilities affected

According to contemporary sources, the following mills were affected in the 1926 Passaic strike:[28]

- Botany Consolidated Mills. — woolen mill

- Dundee Textile. — silk mill

- Forstman and Huffman Mills, Clifton. — woolen mill

- Garfield Worsted Mills. — woolen mill

- Gera Mills. — woolen mill

- National Silk Dyeing Plant, East Paterson. — dye plant

- New Jersey Spinning Company. — woolen mill

- Passaic Worsted Spinning. — woolen mill

- United Piece Dye Works, Lodi. — dye plant

Footnotes

- David J. Goldberg, A Tale of Two Cities: Labor Organization and Protest in Paterson, Passic, and Lawrence, 1916-1921. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1989; pg. 46.

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Volume 10: The TUEL, 1925-1929. New York: International Publishers, 1994; pg. 143.

- The minimum wage estimate is that of the National Industrial Conference Board, cited in Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, vol. 10, pg. 146.

- Cited in Albert Weisbord, Passaic: The Story of a Struggle Against Starvation Wages and for the Right to Organize. Chicago: Daily Worker Publishing Co., 1926; pg. 18.

- Weisbord, Passaic, pg. 19.

- Weisbord, Passaic, pg. 18.

- Ben Gitlow, "The Passaic Textile Workers Strike," The Workers Monthly, vol. 5, no. 8 (June 1926), pg. 349.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, vol. 10, pg. 147.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement of the United States, vol. 10, pp. 147-148.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, vol. 10, pg. 148.

- Labor Research Department of the Rand School of Social Science, Solon DeLeon and Nathan Fine (eds.), The American Labor Year Book, 1927. New York: Vanguard Press, 1927; pp. 107-107.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, vol. 10, pg. 149.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, vol. 10, pg. 153.

- Ben Gitlow, "The Passaic Textile Workers Strike," pg. 348.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, vol. 10, pg. 150.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, vol. 10, pg. 151.

- The relationship of the film to International Workers Aid was not disguised, with the name of the organization and its logo featured prominently in the titles at the front of the film. See: The Passaic Textile Strike: Prologue. Video available from archive.org. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, vol. 10, pg. 154.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, vol. 10, pg. 157.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, vol. 10, pg. 158.

- David J. Goldberg, "Passaic Textile Strike of 1926," in Mari Jo Buhle, Paul Buhle, and Dan Georgakas (eds.), Encyclopedia of the American Left. First Edition. New York: Garland Publishing Co., 1990; pg. 560.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, vol. 10, pg. 159.

- August Erdie, "The Mills of Passaic Today," Labor Unity, vol. 2, no. 1 (May 1928), pg. 8.

- Erdie, "The Mills of Passaic Today," pg. 9.

- "The Passaic Textile Strike," Library of Congress online, retrieved March 9, 2010.

- "Rediscovered PASSAIC TEXTILE STRIKE footage," the orphan film symposium, February 12, 2008.

- "For the Real Orphans", The 6th Orphan Film Symposium, March 30, 2008, archived from the original on March 3, 2011, retrieved April 1, 2010

- Gitlow, "The Passaic Textile Workers Strike," pg. 347.

Further reading

- Martha Stone Ascher, "Recollections of the Passaic Textile Strike of 1926," Labor's Heritage, vol. 2, no. 2 (April 1990), pp. 4–23.

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Volume 10: The TUEL, 1925-1929. New York: International Publishers, 1994.

- Leona Smith, The Textile Strike of 1926: Passaic, Clifton, Garfield, Lodi, New Jersey. Passaic, NJ: General Relief Committee of Textile Strikers, n.d. [1926].

- David Lee McMullen, Strike! The Radical Insurrections of Ellen Dawson. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2010.

- Paul L. Murphy, with Kermit Hall and David Klaassen, The Passaic Textile Strike of 1926. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Co., 1974.

- Morton Siegel, The Passaic Textile Strike of 1926. PhD dissertation. Columbia University, 1952.

- Mary Heaton Vorse, The Passaic Textile Strike, 1926-1927. Passaic, NJ: General Relief Committee of Textile Strikers, 1927.

- Albert Weisbord, Passaic: The Story of a Struggle against Starvation Wages and for the Right to Organize. Chicago: Daily Worker Publishing Co., 1926.

- J.A. Zumoff, "Hell in New Jersey: The Passaic Textile Strike, Albert Weisbord, and the Communist Party," Journal for the Study of Radicalism, vol. 9, no. 1 (2015), pp. 125–169.

External links

- "Prelude" to The Passaic Textile Strike. Internet Archive.org —first 18 minutes of the 1926 film of the strike.

- American Labor Museum photographs from the Passaic Textile Strike. VCU Libraries Social Welfare History Image Portal.