1967 USS Forrestal fire

On 29 July 1967, a fire broke out on board the aircraft carrier USS Forrestal after an electrical anomaly caused a Zuni rocket on a F-4B Phantom to fire, striking an external fuel tank of an A-4 Skyhawk. The flammable jet fuel spilled across the flight deck, ignited, and triggered a chain-reaction of explosions that killed 134 sailors and injured 161. At the time, Forrestal was engaged in combat operations in the Gulf of Tonkin, during the Vietnam War. The ship survived, but with damage exceeding US$72 million, not including the damage to aircraft.[2][3] Future United States Senator John McCain and future four-star admiral and U.S. Pacific Fleet Commander Ronald J. Zlatoper were among the survivors. Another on-board officer, Lieutenant Tom Treanore, later returned to the ship as its commander and retired an admiral.[4]

_stands_by_to_assist_the_burning_USS_Forrestal_(CVA-59)%252C_29_July_1967_(USN_1124775).jpg.webp) USS Forrestal on fire, the worst US carrier fire since World War II; the destroyer Rupertus maneuvers to within 20 ft (6 m) to use fire hoses. | |

USS Forrestal (South China Sea) | |

| Date | 29 July 1967 |

|---|---|

| Time | 02:52 UTC (10:52 a.m. Hotel time) |

| Location | Gulf of Tonkin, 19°9′5″N 107°23′5″E[1] |

| Outcome | Capt. John K. Beling absolved of responsibility; no crew members charged. Ship in dry dock for five months. |

| Casualties | |

| Repair costs: US$72 million[2] | |

| Aircraft lost: seven F-4B Phantom II; eleven A-4E Skyhawks; and three RA-5C Vigilantes; 40 others damaged | |

| Deaths | 134 dead[2] |

| Non-fatal injuries | 161 injured[2] |

The disaster prompted the Navy to revise its fire fighting practices. It also modified its weapon handling procedures and installed a deck wash down system on all carriers. The newly established Farrier Fire Fighting School Learning Site in Norfolk, Virginia was named after Chief Gerald W. Farrier, the commander of Damage Control Team 8, who was among the first to die in the fire and explosions.

Background

_underway_at_sea_on_31_May_1962_(KN-4507).jpg.webp)

_anchored_off_Naples%252C_Italy%252C_on_20_October_1960_(USN_1050684).jpg.webp)

Arrival in Gulf of Tonkin

Forrestal departed her home port in Norfolk, Virginia in early June 1967. After she completed required inspections for the upcoming West Pacific cruise, she sailed to Brazil for a show of force. She then traveled east around the Horn of Africa and visited Naval Air Station Cubi Point in the Philippine Islands before sailing to Yankee Station in the Gulf of Tonkin on 25 July.

After arrival at Yankee Station, aircraft from Attack Carrier Air Wing 17 flew approximately 150 missions against targets in North Vietnam over four days.[5]

Vietnam bombing campaign

The ongoing naval bombing campaign during 1967 originating at Yankee Station represented by far the most intense and sustained air attack operation in the U.S. Navy's history. The demand for general-purpose bombs (e.g., "iron bombs") greatly exceeded production. The inventory of bombs dwindled throughout 1966 and became critically low by 1967.[6] This was particularly true for the new 1,000 lb (450 kg) Mark 83, which the Navy favored for its power-to-size ratio. A carrier-launched A-4 Skyhawk, the Navy's standard light attack / ground attack aircraft, could carry either a single 2,000 lb (910 kg) bomb, or two 1,000 lb bombs. The latter gave it the ability to strike two separate hardened targets in a single sortie, which was more effective in most circumstances.

The U.S. Air Force's primary ground attack aircraft in Vietnam was the much heavier, land-based, F-105 Thunderchief. It could simultaneously carry two 3,000 lb (1,360 kg) M118 bombs and four 750 lb (340 kg) M117 bombs. The Air Force had a large supply of these bombs, and did not rely as heavily on the limited supply of 1,000 lb bombs as did the Navy.

Issues with Zuni rockets

In addition to bombs, the ground attack aircraft carried unguided 5 in (127 mm) Mk-32 "Zuni" rockets. These rockets were in wide use although they had a reputation for electrical difficulties and accidental firing.[7] It was common for aircraft to launch with six or more rocket packs, each containing four rockets.[7]

Specialized fire-fighting teams

Based on lessons learned during Japanese attacks on vessels during World War II, most sailors on board ships after World War II received training in fighting shipboard fires. These lessons were gradually lost and by 1967, the U.S. Navy had reverted to the Japanese model at Midway and relied on specialized, highly trained damage control and fire-fighting teams.[8]

The damage control team specializing in on-deck firefighting for Forrestal was Damage Control Team No. 8, led by Chief Aviation Boatswain's Mate Gerald Farrier. They had been shown films during training of Navy ordnance tests demonstrating how a 1,000 lb bomb could be directly exposed to a jet fuel fire for a full ten minutes and still be extinguished and cooled without an explosive cook-off.[9]:126 However, these tests were conducted using the new Mark 83 1,000 lb bombs, which featured relatively stable Composition H6 explosive and thicker, heat-resistant cases, compared to their predecessors. Because it is relatively insensitive to heat, shock and electricity, Composition H6 is still used as of 2021 in many types of naval ordnance. It is also designed to deflagrate instead of detonate when it reaches its ignition point in a fire, either melting the case and producing no explosion at all, or, at most, a subsonic low order detonation at a fraction of its normal power.[9]:85

Unstable ordnance received

On 28 July, the day before the accident, Forrestal was resupplied with ordnance by the ammunition ship USS Diamond Head. The load included sixteen 1,000 lb AN/M65A1 "fat boy" bombs (so nicknamed because of their short, rotund shape), which Diamond Head had picked up from Subic Bay Naval Base and were intended for the next day's second bombing sortie. Some of the batch of AN-M65A1s Forrestal received were more than a decade old, having spent a portion of that exposed to the heat and humidity of Okinawa or Guam,[10] eventually being improperly stored in open-air Quonset huts at a disused ammunition dump on the periphery of Subic Bay Naval Base. Unlike the thick-cased Mark 83 bombs filled with Composition H6, the AN/M65A1 bombs were thin-skinned and filled with Composition B, an older explosive with greater shock and heat sensitivity.[11]

Composition B also had the dangerous tendency to become more powerful (up to 50% by weight) and more sensitive if it was old or improperly stored. Forrestal's ordnance handlers had never even seen an AN/M65A1 before, and to their shock, the bombs delivered from Diamond Head were in terrible condition; coated with "decades of accumulated rust and grime" and still in their original packing crates (now moldy and rotten); some were stamped with production dates as early as 1953. Most dangerous of all, several bombs were seen to be leaking liquid paraffin phlegmatizing agent from their seams, an unmistakable sign that the bomb's explosive filler had degenerated with excessive age, and exposure to heat and moisture.[9]:87[11]

According to Lieutenant R. R. "Rocky" Pratt, a naval aviator attached to VA-106,[13] the concern felt by Forrestal's ordnance handlers was striking, with many afraid to even handle the bombs; one officer wondered out loud if they would survive the shock of a catapult-assisted launch without spontaneously detonating, and others suggested they immediately jettison them.[9]:86 Forrestal's ordnance officers reported the situation up the chain of command to the ship's commanding officer, Captain John Beling, and informed him the bombs were, in their assessment, an imminent danger to the ship and should be immediately jettisoned overboard.[8][6]

Faced with this, but still needing 1,000 lb bombs for the next day's missions, Beling demanded Diamond Head take the AN-M65A1s back in exchange for new Mark 83s,[9]:88 but was told by Diamond Head that they had none to give him. The AN-M65A1 bombs had been returned to service specifically because there were not enough Mark 83s to go around. According to one crew member on Diamond Head, when they had arrived at Subic Bay to pick up their load of ordnance for the carriers, the base personnel who had prepared the AN-M65A1 bombs for transfer assumed Diamond Head had been ordered to dump them at sea on the way back to Yankee Station. When notified that the bombs were actually destined for active service in the carrier fleet, the commanding officer of the naval ordnance detachment at Subic Bay was so shocked that he initially refused the transfer, believing a paperwork mistake had been made. At the risk of delaying Diamond Head's departure, he refused to sign the transfer forms until receiving written orders from CINCPAC on the teleprinter, explicitly absolving his detachment of responsibility for the bombs' terrible condition.[6]

Unstable bombs stored on deck

With orders to conduct strike missions over North Vietnam the next day, and with no replacement bombs available, Captain Beling reluctantly concluded that he had no choice but to accept the AN-M65A1 bombs in their current condition.[8][14][15] In one concession to the demands of the ordnance handlers, Beling agreed to store all 16 bombs alone on deck in the "bomb farm" area between the starboard rail and the carrier's island until they were loaded for the next day's missions. Standard procedure was to store them in the ship's magazine with the rest of the air wing's ordnance; had they been stored as standard, an accidental detonation could easily have destroyed the ship.[9]:273–74

Fire and explosions

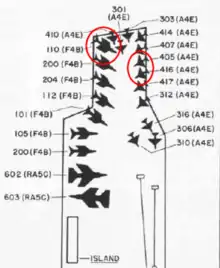

While preparing for the second sortie of the day, the aft portion of the flight deck was packed wing-to-wing with twelve A-4E Skyhawk, seven F-4B Phantom II, and two Vigilante aircraft. A total of 27 aircraft were on deck, fully loaded with bombs, rockets, ammunition, and fuel. Several tons of bombs were stored on wooden pallets on deck in the bomb farm.[16] An F-4B Phantom II (No. 110, BuNo 153061), flown by Lieutenant Commander James E. Bangert and Lieutenant (JG) Lawrence E. McKay from VF-11,[1] was positioned on the aft starboard corner of the deck, pointing about 45 degrees across the ship.[1] It was armed with LAU-10 underwing rocket pods, each containing four unguided 5 in (127.0 mm) Mk-32 "Zuni" rockets. The Zuni was protected from launching by a safety pin that was only to be removed prior to launch from the catapult.[7]:57

Zuni rocket launched

At about 10:51 (local time) on 29 July, an electrical power surge in Phantom No. 110 occurred during the switch from external to internal power. The electrical surge caused one of the four 5-inch Mk-32 Zuni unguided rockets in a pod on external stores station 2 (port inboard station) to fire.[6] The rocket was later determined to be missing the rocket safety pin, allowing the rocket to launch. The rocket flew about 100 feet (30 m) across the flight deck, likely severing the arm of a crewman, and ruptured a 400-US-gallon (1,500 l; 330 imp gal) wing-mounted external fuel tank on a Skyhawk from Attack Squadron 46 (VA-46) awaiting launch.[1][7]:34, 93

Aircraft struck

The official Navy investigation identified the Skyhawk struck by the Zuni as aircraft No. 405, piloted by Lieutenant Commander Fred D. White.[2][18] Lieutenant Commander John McCain stated in his 1999 book Faith of My Fathers that the missile struck his aircraft, alongside White's A-4 Skyhawk. "On that Saturday morning in July, as I sat in the cockpit of my A-4 preparing to take off, a rocket hit the fuel tank under my airplane."[19] Later accounts relying on his book also state that the rocket struck his A-4 Skyhawk.[20][21][22]

The Zuni rocket's warhead safety mechanism prevented it from detonating. The rocket broke apart on impact with the external fuel tank.[7]:34 The highly flammable JP-5 fuel spread on the deck under White's and McCain's A-4s, ignited by numerous fragments of burning rocket propellant, and causing an instantaneous conflagration. A sailor standing about 100 feet forward was struck by a fragment of the Zuni or the exploding fuel tank. A fragment also punctured the centerline external fuel tank of A-4 #310, positioned just aft of the jet blast deflector of catapult number 3. The resulting fire was fanned by 32-knot (59 km/h; 37 mph) winds and the exhaust of at least three jets.[15] Fire quarters and then general quarters were sounded at 10:52 and 10:53. Condition ZEBRA was declared at 10:59, requiring all hands to secure the ship for maximum survivability, including closing the fire-proof steel doors that separate the ship's compartments.[23]

The official report states that one Korean War-era 1,000 lb AN-M65 bomb fell from an A-4 Skyhawk to the deck;[24][25] other reports say two.[14][8] The bomb fell in a pool of burning fuel between White's and McCain's aircraft.

Damage Control Team No. 8, led by Chief Gerald W. Farrier, were the first responders to any incident on the flight deck. They immediately took action. Farrier, without taking the time to locate and put on protective clothing, immediately attempted to smother the bomb with a PKP fire extinguisher, attempting to delay the fuel fire from spreading and give the pilots time to escape their aircraft. Based on their training, the team believed they had a ten-minute window to extinguish the fire before the bombs casing would melt resulting in a low-order explosion.[26]

The pilots, preparing to launch, were strapped into their aircraft. When the fire started and quickly spread, they immediately attempted to escape their aircraft. McCain, pilot of A-4 Skyhawk side No. 416, next to White's, was among the first to notice the flames, and escaped by scrambling down the nose of his A-4 and jumping off the refueling probe. Lt. Cmdr. Robert "Bo" Browning, in an A-4E Skyhawk on the port side, escaped by crossing the flight deck and ducking under the tails of F-4B Phantoms spotted along the starboard side.[24] CVW-17 operations officer, Lt. Cmdr. Herbert A. Hope of VA-46, escaped by jumping out of the Skyhawk cockpit and rolling off the flight deck and into the starboard man-overboard net. He went to the hangar deck and took command of a firefighting team.

Bombs detonate

Despite Farrier's constant effort to cool the bomb that had fallen to the deck, the casing suddenly split open and the explosive began to burn brightly. Farrier, recognizing that a lethal cook-off was imminent, shouted for his firefighters to withdraw, but the bomb detonated—one minute and 36 seconds after the start of the fire.[9]:123–24 The unstable Composition B in the old bombs enhanced the power of the explosions.[8] Thirty-five personnel were in close proximity to the blast. Two fire control teams were virtually destroyed; Farrier and all but three of his men were killed instantly. Twenty-seven men were injured.

"I saw a dozen people running... into the fire, just before the bomb cooked off," Lt. Cmdr. Browning later said.[24][26] McCain saw another pilot on fire, and turned to help him, when the first bomb detonated. McCain was knocked backwards 10 feet, struck by shrapnel and wounded. White managed to get out of his burning aircraft but was killed by the detonation of the first bomb.[26] Not all of the pilots were able to get out of their aircraft in time. Lt Ken McMillen escaped. LT(JG) Don Dameworth and LT(JG) David Dollarhide were injured escaping their aircraft. Lt. Cmdrs Gerry Stark and Dennis Barton were missing.[26]

Fire enters lower decks

The first bomb detonation destroyed White's and McCain's aircraft, blew a crater in the armored flight deck, and sprayed the deck and crew with bomb fragments and shrapnel from the destroyed aircraft. Burning fuel poured through the hole in the deck into occupied berthing compartments below. In the tightly packed formation on the aft deck, every aircraft, all fully fueled and bomb-laden, was damaged. All seven F-4s caught fire.[8]

Lieutenant James J. Campbell recoiled for a few moments in stunned dismay as burning torches tumbled toward him, until their screams stirred him to action.[1] Several men jumped or were blown into the ocean. Neighboring ships came alongside and pulled the men from the water.[26] When Browning got back on deck, he recalled, "The port quarter of the flight deck where I was is no longer there."[1]

Two more of the unstable 1,000 lb bombs exploded 10 seconds after the first, and a fourth blew up 44 seconds after that. A total of ten bombs exploded during the fire.[27] Bodies and debris were hurled as far as the bow of the ship.

In less than five minutes, seven or eight 1,000-pound bombs,[8][28] one 750-pound bomb, one 500-pound (227 kg) bomb, and several missile and rocket warheads heated by the fire exploded with varying degrees of violence.[28] Several of the explosions of the 1,000-pound Korean War-era AN-M65 Composition B bombs were estimated to be as much as 50% more powerful than a standard 1,000-pound bomb, due to the badly degraded Composition B. The ninth explosion was attributed to a sympathetic detonation between an AN-M65 and a newer 500 lb M117 H6 bomb that were positioned next to each other. The other H6-based bombs performed as designed and either burned on the deck or were jettisoned, but did not detonate under the heat of the fires.[8] The ongoing detonations prevented fire suppression efforts during the first critical minutes of the disaster.

The explosions tore seven holes in the flight deck. About 40,000 US gallons (150,000 l; 33,000 imp gal) of burning jet fuel from ruptured aircraft tanks poured across the deck and through the holes in the deck into the aft hangar bay and berthing compartments. The explosions and fire killed fifty night crew personnel who were sleeping in berthing compartments below the aft portion of the flight deck. Forty-one additional crew members were killed in internal compartments in the aft portion of Forrestal.[8]

Personnel from all over the ship rallied to fight the fires and control further damage. They pushed aircraft, missiles, rockets, bombs, and burning fragments over the side. Sailors manually jettisoned numerous 250 and 500 lb bombs by rolling them along the deck and off the side. Sailors without training in firefighting and damage control took over for the depleted damage control teams. Unknowingly, inexperienced hose teams using seawater washed away the efforts of others attempting to smother the fire with foam.[26][1]

Fires controlled

The destroyer USS George K. MacKenzie pulled men from the water and directed its fire hoses on the burning ship. Another destroyer, USS Rupertus, maneuvered as close as 20 feet (6.1 m) to Forrestal for 90 minutes, directing her own on-board fire hoses at the burning flight and hangar deck on the starboard side, and at the port-side aft 5-inch gun mount.[29] Rear Admiral and Task Group commander Harvey P. Lanham, aboard Forrestal, called the actions of Rupertus commanding officer Commander Edwin Burke[30] an "act of magnificent seamanship".[29] At 11:47 am, Forrestal reported the flight deck fire was under control. About 30 minutes later, they had put out the flight deck fires. Fire fighting crews continued to fight fires below deck for many more hours.[29]

Undetonated bombs were continually found during the afternoon. LT(JG) Robert Cates, the carrier's explosive ordnance demolition officer, recounted later how he had "noticed that there was a 500-pound bomb and a 750-pound bomb in the middle of the flight deck... that were still smoking. They hadn't detonated or anything; they were just sitting there smoking. So I went up and defused them and had them jettisoned." Another sailor volunteered to be lowered by line through a hole in the flight deck to defuse a live bomb that had dropped to the 03 level—even though the compartment was still on fire and full of smoke. Later on, Cates had himself lowered into the compartment to attach a line to the bomb so it could be hauled up to the deck and jettisoned.[25]

Throughout the day, the ship's medical staff worked in dangerous conditions to assist their comrades. The number of casualties quickly overwhelmed the ship's medical teams, and Forrestal was escorted by USS Henry W. Tucker to rendezvous with hospital ship USS Repose at 20:54, allowing the crew to begin transferring the dead and wounded at 22:53.[1] Firefighter Milt Crutchley said, "The worst was going back into the burned-out areas later and finding your dead and wounded shipmates." He said it was extremely difficult to remove charred, blackened bodies locked in rigor mortis "while maintaining some sort of dignity for your fallen comrades."[31]

At 5:05, a muster of Forrestal crewmen—both in the carrier and aboard other ships—was begun. It took many hours to account for the ship's crew. Wounded and dead had been transferred to other ships, and some men were missing, either burned beyond recognition or blown overboard. At 6:44 pm, fires were still burning in the ship's carpenter shop and in the aft compartments. At 8:33 pm, the fires in the 02 and 03 levels were contained, but the areas were still too hot to enter. Fire fighting was greatly hampered because of smoke and heat. Crew members cut additional holes in the flight deck to help fight fires in the compartments below. At 12:20 am, July 30, 14 hours after the fires had begun, all the fires were controlled. Forrestal crew members continued to put out hot spots, clear smoke, and cool hot steel on the 02 and 03 levels. The fires were declared out at 4:00 am.[25][1]

Aftermath

The fire left 134 men dead[32] and 161 more injured.[2] It was the worst loss of life on a U.S. Navy ship since World War II.[21] Of the 73 aircraft aboard the carrier, 21 were destroyed and 40 were damaged.

Twenty-one aircraft were stricken from naval inventory: seven F-4B Phantom IIs, eleven A-4E Skyhawks, and three RA-5C Vigilantes.[1]

The ship's chaplains held a memorial service in Hangar Bay One for the crewmen which was attended by more than 2,000 of Forrestal's crew.

Temporary repairs

On 31 July, Forrestal arrived at Naval Air Station Cubi Point in the Philippines, to undertake repairs sufficient to allow the ship to return to the United States. During welcoming ceremonies, a fire alarm signal alerted crews to a fire in mattresses within the burned-out compartments.[19]

Investigation begun

A special group, the Aircraft Carrier Safety Review Panel, led by Rear Admiral Forsyth Massey, was convened on 15 August in the Philippines. Owing to the necessity of returning the ship to the United States for repair, the panel acted quickly to interview personnel on board the ship.[34]

Ordnance issues found

_cost_of_the_fire.jpg.webp)

Investigators identified issues with stray voltage in the circuitry of the LAU-10 rocket launchers and Zuni missiles. They also identified issues with the aging 1,000 lb "fat bombs" carried for the strike, which were discovered to have dated from the Korean War in 1953.[1]

Safety procedures overridden

The board of investigation stated, "Poor and outdated doctrinal and technical documentation of ordnance and aircraft equipment and procedures, evident at all levels of command, was a contributing cause of the accidental rocket firing." However, the doctrine and procedures employed were not unique to Forrestal. Other carriers had problems with the Zuni rockets.[6]

The investigation found that safety regulations should have prevented the Zuni rocket from firing. A triple ejector rack (TER) electrical safety pin was designed to prevent any electrical signal from reaching the rockets before the aircraft was launched, but it was also known that high winds could sometimes catch the attached tags and blow them free. In addition to the pin, a "pigtail" connected the electrical wiring of the missile to the rocket pod. US Navy regulations required the pigtail be connected only when the aircraft was attached to the catapult and ready to launch, but the ordnance officers found this slowed down the launch rate.[7]:57

The Navy investigation found that four weeks before the fire, Forrestal's Weapons Coordination Board, along with members of the Weapons Planning Board, held a meeting to discuss the issue of attaching the pigtail at the catapult. Launches were sometimes delayed when a crew member had difficulty completing the connection. They agreed on a deviation from standard procedure. In a memorandum of the meeting, they agreed to "Allow ordnance personnel to connect pigtails 'in the pack', prior to taxi, leaving only safety pin removal at the cat." The memo, written on 8 July 1967, was circulated to the ship's operations officer. But the memo and the decision were never communicated to Captain Beling, the ship's commanding officer, who was required to approve such decisions.[35]:65

Causes identified

The official inquiry found that the ordnance crew acted immediately on the Weapons Coordination Board's decision. They found that the pigtail was connected early, that the TER pin on the faulty Zuni missile was likely blown free, and that the missile fired when a power surge occurred as the pilot transferred his systems from external to internal power.[7]:57 Their report concluded that a ZUNI rocket on the portside TER-7 on external stores station 2 of F-4B No. 110 of VF-11, spotted on the extreme starboard quarter of the flight deck, struck A-4 No. 405, piloted by Lt. Cmdr. Fred D. White, on the port side of the aft deck. The accidental firing was due to the simultaneous malfunction of three components: CA42282 pylon electrical disconnect, TER-7 safety switch, and LAU-10/A shorting device. They concluded that the CA42282 pylon electrical disconnect had a design defect, and found that the TER-7 safety pin was poorly designed, making it easy to confuse with ordnance pins used in the AERO-7 Sparrow Launcher, which if used by mistake would not operate effectively.[7]

Drydock repairs

When temporary repairs in the Philippines were completed, Forrestal departed on 11 August, arriving at Naval Station Mayport in Florida on 12 September to disembark the remaining aircraft and air group personnel stationed in Florida. Two days later, Forrestal returned to Norfolk to be welcomed home by over 3,000 family members and friends of the crew, gathered on Pier 12 and onboard Randolph, Forrestal's host ship.[1]

From 19 September 1967 to 8 April 1968, Forrestal underwent repairs in Norfolk Naval Shipyard, beginning with removal of the starboard deck-edge elevator, which was stuck in place. It had to be cut from the ship while being supported by the shipyard's hammerhead crane. The carrier occupied drydock number 8 from 21 September 1967, until 10 February 1968, displacing USS John King, an oil tanker, and a minesweeper that were occupying the drydock. During the post-fire refit, 175 feet (53 m) of the flight deck was replaced, along with about 200 compartments on the 03, 02, 01 decks. The ship's four aft 5"/54 caliber Mark 42 guns were removed. The forward four guns had been removed prior to 1962. The repair cost about $72 million (equal to more than $602 million in 2019 dollars), and took nearly five months to complete.[36][16][37]

Beling reassigned

Captain Beling, as an Admiral-selectee, received orders to report to Washington, D.C., as the Director of Development Programs in Naval Operations, reporting to Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Thomas H. Moorer. On 18 September 1967, Captain Robert B. Baldwin assumed command of Forrestal.[38] From 8 to 15 April 1968, he sailed the ship down the Elizabeth River and out into the waters off the Virginia Capes for post-repair trials, the ship's first time at sea in 207 days. While accomplishing trials, the ship also recorded its first arrested landing since the fire, when Commander Robert E. Ferguson, Commander, CVW-17, landed on board.[1]

Beling absolved of responsibility

The Naval investigation panel's findings were released on 18 October. They concluded Beling knew that the Zuni missiles had a history of problems, and he should have made more effort to confirm that the ordnance crew was following procedure in handling the ordnance.[7] They ruled he was not responsible for the disaster, but he was nonetheless transferred to staff work, and never returned to active command.

Beling was assigned temporary duty on the staff of Admiral Ephraim P. Holmes, Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet. Holmes disagreed with many portions of the Navy's report into the Forrestal disaster, including the section clearing Beling. He had Beling assigned to his staff so he could issue a letter of reprimand. By holding Beling responsible he would effectively end his career. Holmes attached the reprimand to the final report, but when Admiral Moorer endorsed the report, he ordered Admiral Holmes to rescind and remove the reprimand.[9][8]

The investigation panel recommended several changes to safety procedures aboard carriers. This included development of a remote-control fire-fighting system for the flight deck, development of more stable ordnance, improvement in survival equipment, and increased training in fire survival.[34] The U.S. Navy implemented safety reviews for weapons systems brought on board ships for use or for transshipment. This evaluation is still carried out by the Weapon System Explosives Safety Review Board.[6][9]:123,124 The fire aboard Forrestal was the second of three serious fires to strike American carriers in the 1960s. A 1966 fire aboard USS Oriskany killed 44 and injured 138 and a 1969 fire aboard USS Enterprise killed 28 and injured 314. The greatest loss of life on a U.S. Navy ship since World War II was when the destroyer USS Hobson collided with the aircraft carrier USS Wasp on 26 April 1952, breaking in half, killing 176.

Incorrect NASA report

A 1995 report, NASA Reference Publication 1374, incorrectly described the Forrestal fire as a result of electromagnetic interference. It states, "a Navy jet landing on the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Forrestal experienced the uncommanded release of munitions that struck a fully armed and fueled fighter on deck... This accident was caused by the landing aircraft being illuminated by carrier based radar, and the resulting EMI sent an unwanted signal to the weapons system."[39]:7

This incorrect description has been cited as a cautionary tale on the importance of avoiding electromagnetic interference.[40][41] The report itself lacks an accurate reference to the fire. While text contains a superscript pointing to item 12 in the references section, item 12 in the reference section is to "Von Achen, W.: The Apache Helicopter: An EMI Case History. Compliance Engineering, Fall, 1991."[39]:19

Legacy

Eighteen crewmen were buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Names of the dead are also listed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

On 29 July 2017, the USS Forrestal Association commemorated the 50th anniversary of the incident. Members of the military, survivors of the disaster, and family members gathered to memorialize those lost in this incident. Active duty personnel presented American flags to represent each sailor who died.[42][43]

The non-profit USS Forrestal Association was formed in 1990 to preserve the memory of those lost in the tragedy.[42]

Farrier Fire Fighting School established

The Farrier Fire Fighting School Learning Site in Norfolk, Virginia is named after Chief Gerald W. Farrier, the commander of Damage Control Team 8, who was killed in the initial explosion. The school hosts an annual memorial remembering the sailors who lost their lives aboard the Forrestal.[44]

Lessons learned

%252C_in_1969.jpg.webp)

The fire revealed that Forrestal lacked a heavy-duty, armored forklift needed to jettison aircraft, particularly heavier planes like the RA-5C Vigilante, as well as heavy or damaged ordnance.[1]

The United States Navy uses the Forrestal fire and the lessons learned from it when teaching damage control and ammunition safety. The flight-deck film of the flight operations, titled "Learn or Burn", became mandatory viewing for firefighting trainees.[1] All new Navy recruits are required to view a training video titled Trial by Fire: A Carrier Fights for Life,[45][25] produced from footage of the fire and damage control efforts, both successful and unsuccessful.

Footage revealed that damage-control teams sprayed firefighting foam on the deck to smother the burning fuel, which was the correct procedure, but their efforts were negated by crewmen on the other side of the deck who sprayed seawater, which washed the foam away. The seawater worsened the situation by washing burning fuel through the holes in the flight deck and into the decks below. In response, a "wash down" system, which floods the flight deck with foam or water, was incorporated into all carriers, with the first being installed aboard Franklin D. Roosevelt during her 1968–1969 refit.[6][46] Many other fire-safety improvements also stemmed from this incident.[6]

Due to the first bomb blast, which killed nearly all of the trained firefighters on the ship, the remaining crew, who had no formal firefighting training, were forced to improvise.[47] All current Navy recruits receive week-long training in compartment identification, fixed and portable extinguishers, battle dress, self-contained breathing apparatus and emergency escape breathing devices. Recruits are tested on their knowledge and skills by having to use portable extinguishers and charged hoses to fight fires, as well as demonstrating the ability to egress from compartments that are heated and filled with smoke.

Media

The disaster was a major news story and was featured under the headline "Inferno at Sea" on the cover of the 11 August 1967, issue of Life magazine.[48]

The incident was featured on the first episode of the History Channel's Shockwave[49] and the third episode of the second season of the National Geographic Channel's Seconds From Disaster.

References

- "USS Forrestal (CV-59)". DANFS. Naval Historical Center. 2 August 2007. Archived from the original on 20 March 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- Stewart, Henry P. (2004). The Impact of the USS Forrestal's 1967 Fire on United States Navy Shipboard Damage Control (PDF) (Master's thesis). Fort Leavenworth, KS: United States Army Command and General Staff College. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- "USS Forrestal (CVA 59)". US Navy Damage control museum. Archived from the original on 7 February 2008.

- "Remarks at USS Forrestal Forty Year Memorial Tribute". Farrier Fire Fighting School, Norfolk, Virginia. 27 July 2007 Tom Wimberly, Captain, U. S. Navy (Retired)

- "USS Forrestal CVA-59". US Navy. 15 June 2009. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- Cox, Samuel J. (July 2017). "H-008-6 USS Forrestal Disaster". www.history.navy.mil. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "Official investigation Part 3" (PDF). Judge Advocate General. 19 September 1967. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- "U.S.S. Forrestal Fire 1967 | A-4 Skyhawk Association". a4skyhawk.info. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Freeman, Gregory A. (2004). Sailors to the End: The Deadly Fire on the USS Forrestal and the Heroes Who Fought It. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0060936907.

- Baron, Scott; Wise, Jr, James (2013). Dangerous Games: Faces, Incidents, and Casualties of the Cold War. Naval Institute Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-1612514529. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- "A U.S. Navy Aircraft Carrier's Greatest Fear (And It's Not Russia or China)". 26 August 2017. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- "Gladiator Helmet". Gladiator Reunion Group. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- "Bud Dougherty Collection: Disaster on the USS Forrestal". Arlington Historical Society. 18 June 2017. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Collins, Elizabeth M. (27 July 2017). "Fire Aboard Ship". navy.mil. All Hands. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- "How the 1967 Fire on USS Forrestal Improved Future U.S. Navy Damage Control Readiness". The Sextant. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Cherney, Mike (28 July 2007). "Veterans salute sailors killed aboard carrier". The Virginian Pilot. Hampton Roads. pp. 1, 8. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- McCain, John (September 1974). "The 1967 Aircraft Carrier Fire That Nearly Killed John McCain". Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Ringle, Ken (2 August 1997). "A Navy Ship's Trial by Fire". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- "Rocket causes deadly fire on aircraft carrier - Jul 29, 1967 - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "Forrestal, Navy's 1st 'supercarrier,' changes hands in one-cent transaction". Stars and Stripes. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "Material Conditions of Readiness - 14325_341". navyadvancement.tpub.com. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Browning, LCdr. Robert "Bo". "Personal account of the USS Forrestal fire, July 29, 1967". Navy Safety Center. Archived from the original on 6 February 2004. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- "The Forrestal Fire". Archived from the original on 8 February 2006. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- "A Ship Full of Heroes" (PDF). All Hands. pp. 7–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2004. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- "USS Forrestal fire commemoration a reminder of 'heroism, service and sacrifice'". Pensacola News Journal. 29 July 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Beauregard, Raymond L. "The USS Forrestal (CVA-59) fire and munition explosions | The History of Insensitive Munitions". www.insensitivemunitions.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "The Forrestal Fire, July 29, 1967 Ship's Logs". navsource.org. 14 November 2011. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- "USS Rupertus (DD-851)". navsource.org. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- Ringle, Ken (2 August 1997). "A Navy Ship's Trial by Fire". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- Coffelt, John (24 July 2012). "Forty-five years later, veteran remembers worst naval disaster since WW II". Manchester Times. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

Before the sun came up that Saturday morning, Seaman Kenneth Dyke fell into the warm waters 60 miles off the Gulf of Tonkin where the ship was taking part in operations at Yankee Station, according to the online records of the ship's log.

- "The Tragic Fire July 29, 1967". forrestal.org. Archived from the original on 21 February 2006. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- "Fire and Explosion aboard USS Forrestal (CVA-59) Part 2" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "The USS Forrestal (CVA-59) fire and munition explosions | The History of Insensitive Munitions". www.insensitivemunitions.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "Aircraft Carrier Photo Index: USS Forrestal (CVA-59)". www.navsource.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "Aircraft Carrier Photo Index: USS Forrestal (CVA-59)". www.navsource.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- Leach, R.D. (July 1995). Alexander, M.B. (ed.). "Electronic Systems Failures and Anomalies Attributed to Electromagnetic Interference" (PDF). Marshall Space Flight Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- David H. Harland and Ralph D. Lorenz, Space System Failures, p. 240, ISBN 0-387-21519-0, Springer-Praxis, 2005

- William Pentland, Yes, Our Gadgets Really Threaten Planes Archived 22 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Forbes, 10 September 2012

- "USS Forrestal Tragedy Remembered 50 Years Later". DVIDS. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- Software, Web Easy Professional Avanquest. "50 Year Anniversary USS FORESTALL Fire Memorial Ceremony in Washington D.C." www.va106vf62.org. USS FORRESTAL CVA 59. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Jackson, MC3 Shane A. "USS Forrestal's fallen remembered at Farrier School ceremony". Military News. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- "Trial by Fire: A Carrier Fights for Life". NTIS. 1973. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "History". USS Franklin D. Roosevelt. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- USS Forrestal Mishap July 29, 1967. 25 November 2006. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- Nowicki, Dan (28 July 2017). "Sen. John McCain barely escaped death 50 years ago in the USS Forrestal disaster". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- "Watch Shockwave #1 Full Episode - Shockwave". HISTORY. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

This article contains content in the public domain originally published by the U.S. government.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1967 USS Forrestal fire. |

- US Navy Inves - Fire and explosions aboard USS Forrestal (CV 59) Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 (Official investigation) 19 Sep 1967 Judge Advocate General

- US Navy. Forrestal fire. from Naval Aviation News, October 1967.

- Personal account of the USS Forrestal fire, July 29, 1967 at the Wayback Machine (archived 20 April 2009)

- Virtual Wall: A Memorial to the men who died in the Forrestal fire

- US Navy. Witness to History: USS Forrestal Fire. 1 August 2002.

- Did You Know: The terrible fire aboard the USS Forrestal was the worst single Naval casualty event of the Viet Nam War? at the Wayback Machine (archived 5 November 2004)

- "US Navy Damage Control Museum: USS Forrestal". Archived from the original on 6 October 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- NavSource.org: The Forrestal Fire, 29 July 1967, Ship's Logs

- "USS Forrestal". at ArlingtonCemetery•net. An unofficial website. Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- Video

- Video of USS Forrestal Mishap 29 July 1967 on YouTube

- Trial by Fire: A Carrier Fights for Life (US Navy Training film via Internet Archive)