Abelardo L. Rodríguez

Abelardo Rodríguez Luján, commonly known as Abelardo L. Rodríguez (Spanish pronunciation: [aβeˈlaɾðo ˈele roˈðɾiɣes]; May 12, 1889 – February 13, 1967) was the substitute president of Mexico from 1932 to 1934. He completed the term of Pascual Ortiz Rubio after his resignation, during the period known as the Maximato. Former President Plutarco Elías Calles (el jefe Máximo) then held considerable de facto political power, without being president himself. However, Rodríguez was more successful than Ortiz Rubio had been in asserting presidential power against Calles's influence.

Abelardo L. Rodríguez | |

|---|---|

| |

| 50th President of Mexico | |

| In office September 4, 1932 – November 30, 1934 | |

| Preceded by | Pascual Ortiz |

| Succeeded by | Lázaro Cárdenas |

| Governor of Sonora | |

| In office September 13, 1943 – April 15, 1948 | |

| Preceded by | Anselmo Macías Valenzuela |

| Succeeded by | Horacio Sobarzo |

| Secretary of Defense | |

| In office August 2, 1932 – September 4, 1932 | |

| Preceded by | Plutarco Elías Calles |

| Succeeded by | Pablo Quiroga |

| Secretary of Economy | |

| In office January 20, 1932 – August 2, 1932 | |

| Preceded by | Aarón Sáenz Garza |

| Succeeded by | Primo Villa Michel |

| Governor of the North District of the Federal Territory of Baja California | |

| In office 1923–1930 | |

| Preceded by | José Inocente Lugo |

| Succeeded by | José María Tapia |

| Military Commander of Northern Baja California | |

| In office 1921–1929 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Abelardo Rodríguez Luján 12 May 1889 Guaymas, Sonora |

| Died | 13 February 1967 (aged 77) La Jolla, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Political party | National Revolutionary |

| Spouse(s) | Aída Sullivan (1904-1975) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Unit | Military Commander of the Baja California |

| Battles/wars | Mexican Revolution |

Early life and military

Born in San José de Guaymas, Sonora, to a poor family, he worked early in his life in a hardware store, in a copper mine, and as a professional baseball player. He did not finish his primary studies in Nogales, Sonora, only having finished the 4th grade. He joined the Mexican Revolution in 1913 and began moving up the ranks soon afterward. He was a veteran of the campaign against the Yaqui. He became a Colonel in 1916, and at that rank signed the Plan de Agua Prieta,[1] promulgated by Sonoran revolutionary generals Adolfo de la Huerta, Alvaro Obregón and Plutarco Elías Calles. The three generals rebelled against President Venustiano Carranza's government in 1920. In Baja California, the caudillo Esteban Cantú refused to recognize the interim administration of De la Huerta, so De la Huerta and Calles dispatched Rodríguez to oust Cantú, who went into exile. Rodríguez became Military Commander of northern Baja California in 1921, discharging Cantú's troops.[2] During that period he closed most casinos and bars in the border town of Tijuana, which flourished under Cantú as a destination for vice tourism.[3]

Early political positions

In 1923, he became Governor of the North Territory of Baja California and continued as both Military Commander and Governor until 1929. He was invited to join the proposed uprising of General José Gonzalo Escobar in 1929. The Escobar Rebellion failed and Rodríguez demonstrated he was firmly in the camp of Plutarco Elias Calles.[4] He continued one more year as Governor of northern Baja California. In 1932, he held two different cabinet positions, Minister of Industry and Commerce and Minister of War and Marine affairs under president Ortiz Rubio.

Presidency

Election

Since President Ortiz Rubio was determined to resign because of conflicts with Calles, the question of a replacement was in the key matter. Ortiz Rubio signed his resignation on September 2, 1932, and it was conveyed to Congress the following day. Despite the resignation, the presidential cabinet met, significantly at the home of Calles in Cuernavaca. The President of the PNR, General Manuel Pérez Treviño, would convey names of those whom Calles had made known would be acceptable: Finance Minister Alberto J. Pani, General Joaquín Amaro, and General Abelardo L. Rodriguez. Pani bowed out and suggested for Calles to choose Rodríguez. However, four candidates were presented to Congress, with the name of General Juan José Ríos, Secretary of the Interior, added to the other three. A groundswell of support gave the presidency to Rodríguez, who was named by Congress as President of Mexico on 4 September 1932.[5]

Cabinet

His cabinet included Emilio Portes Gil, who had served as interim president before the 1929 general election. Unlike the cabinet of his predecessor Ortiz Rubio, with multiple changes of personnel, Rodríguez's cabinet was on the whole stable.

Asserting power

During Rodríguez's presidency, Calles was not as focused on political issues as before. Calles's health, which had never been particularly good, declined. To compound Calles's personal woes, his young second wife, Leonor Llorente de Calles, was diagnosed with a brain tumor in spring 1932 and died months later after surgery failed. "Calles's health and state of mind constituted the Achilles heel of this powerful leader."[6]

Rodríguez still had to contend with the perception that although he held the title of president, he was not the man in charge, which was seen to be Calles, the so-called Jefe Máximo de later Revolución. Not only Calles was touted in the press in the US as the "Strong Man of Mexico", but in March 1934, US President Franklin Roosevelt wrote Calles a letter "congratulating him on the 'peace and the growing prosperity of Mexico,'" which was to be delivered at a luncheon that Calles was hosting for Josephus Daniels, the new US ambassador to Mexico. Rodríguez learned of the luncheon at Calles's Cuernavaca home to which many Mexican and foreign dignitaries had already been invited by José Manuel Puig Casauranc. Rodríguez was adamant for the lunch to be cancelled since Calles was "simply a private citizen." It was not the prerogative of an ex-president to host such an event. Guests were disinvited on the pretext that Calles had taken ill. "The President maintained that if any such luncheon were to be given it should be given by him and that if a message should come from President Roosevelt it should come to the President of Mexico."[7] The Roosevelt letter to Calles was delivered, but Calles replied that he was not a part of the President's government although greatly esteemed him. The US ambassador months later made another misstep by calling Calles "the strong man of Mexico" in an interview with the Mexican newspaper El Nacional. That made Daniels become called out by Rodríguez, and the ambassador subsequently claimed that he had been misquoted.[8] Daniels wrote in his memoirs that he, Calles, and Puig Casauranc "knew that the man in Chapultepec Castle [the official presidential residence] was the President of Mexico."[9]

Calles still had considerable sway over Rodríguez's ministers, who often consulted with the him when they tried to affect policy. Finance Minister Alberto J. Pani attempted to temper Rodríguez's adoption of deficit spending and objected to the government's anticlerical tendencies. Pani had long been an importance presence in politics, but Rodríguez forced his resignation from the cabinet. As a sop to Calles, who objected to ousting Pani, Rodríguez appointed Calles as Finance Minister.[10]

Education

Rodríguez's government organized the Council of Primary Education in the Federal District and created cultural missions in rural areas. He also established agricultural schools and regional farm schools, as well as schools for teacher education. He also established the Technical Council of Rural Education.

Narciso Bassols was Minister of Education and pursued a policy that took control of education out of the hands of Mexican states and put it under federal control. At issue was the continued influence of the Catholic Church on students. Under Bassols, the proposition that the education should explicitly advocate socialism was to be official policy, and he moved to embed that in the Mexican Constitution. Many parents objected to sex education in the schools, and there was considerable resistance from the Church. Bassols increased teachers' salaries and sought to undermine the influence of teachers' groups. Rodríguez shifted Bassols from Education to the high-level post as Minister of the Interior, and Baddols then resigned. Rodriguez feared the potential of strong moves against the Catholic Church of causing problems for his successor as President.[11]

Relations with Catholic Church

Under Interim President Emilio Portes Gil, the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico and the Mexican government had come to an agreement that would end the Cristero War in 1929. The Catholic Church was displeased that there were continued anti-Catholic moves in parts of the country, especially Jalisco and Chiapas. Pope Pius XI issued an encyclical that objected to Mexican legislation detrimental to Catholic clergy. Rodríguez strongly objected to the encyclical as full of falsehoods and 'would incite the clergy to disobey the Mexican rulings." The Vatican’s representative in Mexico, Apostolic Delegate Archbishop Leopoldo Ruiz y Flóres, tried to say that the Mexican government had misunderstood the Pope's message. Congress demanded his expulsion, and he was put on a plane. Ruiz y Flores then called on Mexican Catholics not to be members of the PNR since it was socialistic and atheistic, and he called for action by the Catholic faithful. "Each Catholic should be converted into a school of Christian doctrine–into a real apostle—and we shall see that the persecution is converted into blessings from Heaven."[12] The strongly anticlerical-Calles, whose policies while president had provoked the Cristero War, called for the expulsion of the papal representative as well as the archbishop of Mexico. The papal representative was already outside the country and would be arrested if he returned. Rodríguez authorized Portes Gil, then Minister of the Interior, to draw up a recommendation, which he could discuss with Calles. Steps were taken against the high clerics, but there was no uprising of Catholics against the government, despite clerical calls for one.[13]

Agriculture, labor, and industry

The government issued the Agrarian Code, which brought together scattered legislation on agrarian matters. Rodríguez renewed efforts to distribute landed estates into the hands of peasants, which had slowed under the Calles administration. Rodríguez promoted the activities of the National Agricultural Credit Bank. For labor, he enacted a minimum wage that was tied to the cost of living in each state. He created the Department of Labor and promoted the trade union movement and protected the workers against management. He established regulations of the Federal Board of Conciliation and Arbitration were issued and created the Federal Office of Labor Defense, of Agencies of Placements, of Dangerous and Unhealthy Work, of Labor Hygiene, of the Federal Labor Inspection and of Preventive Measures of Accidents. He was a supporter of co-operativies, which he considered would distribute the national wealth to be distributed more evenly, and he pressed Congress to issue the Cooperatives Act. Important for future actions on Mexico's petroleum industry was Rodríguez's creation of a private company, Petromex, tied to the government and guarded supply for domestic use and could compete with foreign investors in the industry.[14]

Infrastructure

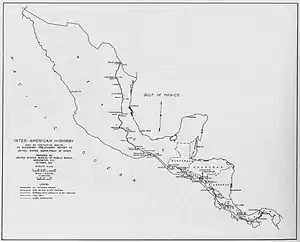

Calles had initiated an ambitious program of road building, which continued in the 1930s under Rodríguez. Roads were would link important centers within Mexico as well as with the United States in the north and Guatemala in the south. They would also connect between remote areas of Mexico and the larger nation. Road building was a form of state building.[15] Construction on the Pan-American Highway saw progress, with a map issued in 1933 showing the route.

Law

During his presidency, he improved the organization and operation of common justice, issuing the Organic Law of the District and Territorial Courts. The federal codes were reviewed and the Federal Law on Criminal Procedures was issued. He organized the Office of the Attorney General, determining the functions of the Federal Public Ministry, which carried out the study of the Law of Protection and issued the Personal Identification, Nationality and Naturalization, Foreign Service and General Mercantile Companies. He also implemented laws related to private charity and monopolies. He issued the Limited Liability and Public Interest Corporation Law. He enacted the Code of Military Justice.

Economy and finance

He established the National Economic Council and created the National Financial bank. He founded the Bank of the Pacific, the Mexican Bank of the West, and the Central Mexican Credit. He reformed the Law of Secretaries of State, transforming the Department of Commerce, Commerce and Labor into the Secretariat of the National Economy, which was responsible for establishing the bases of state interventionism and the managed economy.

Later life

After his term ended on November 30, 1934, Rodríguez returned to private life. When Lázaro Cárdenas became president of Mexico in 1934, initially as a protégé of Calles and then as his political enemy, Rodríguez was aligned with Calles. Cárdenas closed casinos in northern Mexico, depriving Rodríguez and Calles of a significant source of income.[16] In 1943, he was elected Governor of Sonora and taxed Chinese casinos and "recreation centers," a euphemism for opium dens. The income allowed the government to avoid taxing "productive enterprises."[17][18] Rodríguez himself had become a wealthy man from casino income.[19]

He promoted university education and established Sonora's state university. He resigned from his governorship in April 1948, citing health reasons. He returned to his work in business. He started more than 80 companies and participated in approximately 126 other companies.

He died in La Jolla, California, on February 13, 1967.

Honors

- General Abelardo L. Rodríguez International Airport, Tijuana, Baja California

- Presa Abelardo L. Rodríguez, dam over the Tijuana River

- El Sauzal de Rodríguez, Ensenada Municipality, Baja California

- Abelardo L. Rodríguez public park

Playas de Rosarito, Baja California

See also

References

- Dulles, John F.W. Yesterday in Mexico: A Chronicle of the Mexican Revolution, Austin: University of Texas Press 1961, p. 33

- Dulles, Yesterday in Mexico, p. 76.

- Buchenau, Jürgen. Plutarco Elías Calles and the Mexican Revolution. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield 2007, pp. 92, 97

- Dulles, Yesterday in Mexico, p. 424-25

- Dulles, John W. F., Yesterday in Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press 1961, , pp. 540-542, drawing on the description in La jornada instituticional del día cuatro de septiembre de 1932. Juan José Ríos, P. Ortiz Rubio, A.L. Rodríguez, L.L. Leon, A. Sáenz. Mexico City 1932

- Buchenau, Plutarco Elías Calles, p. 162.

- Dulles, Yesterday in Mexico. pp. 557-58

- Dulles, Yesterday in Mexico, p. 559.

- Daniels, Josephus. Shirt-Sleeve Diplomat. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 1947, p. 51.

- Buchenau, Plutarco Elías Calles, pp. 164-65

- Dulles, Yesterday in Mexico, pp. 559-61.

- quoted in Dulles, Yesterday in Mexico p. 563

- Dulles, Yesterday in Mexico. Pp. 563-65

- Buchenau, Plutarco Elías Calles, p. 164.

- Waters, Wendy. "Remapping Identities: Road Construction and Nation Building in Postrevolutionary Mexico" in The Eagle and the Virgin: Nation and Cultural Revolution in Mexico, 1920-1940. Mary Kay Vaughan and Stephen E. Lewis, eds. Durham: Duke University Press 2006

- Schantz, Eric M. "Behind the Noir Border: Tourism, the Vice Racket, and Power Relations in Baja California's Border Zone, 1938-65" in Holiday in Mexico: Critical Reflections on Tourism and Tourist Encounters, Berger, Dina and Andrew Grant Wood, ed. Durham: Duke University Press 2010, pp. 131-32

- Schantz, "Behind the Noir Border," p.141

- Samaniego Lopez, Marco Antonio, "El desarrollo económico durante el gobierno de Abelardo L. Rodríguez" p. 24.

- Gómez Estrada, José Alfredo. Gobierno y casinos: El origen de la riqueza de Abelardo L. Rodríguez. Mexicali: Universidad Autónoma de Baja California 2002.

Further reading

- Buchenau, Jürgen. Plutarco Elías Calles and the Mexican Revolution. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield 2007. ISBN 978-0-7425-3749-1

- Camp, Roderic Ai. Mexican Political Biographies. 2nd edition. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona, 1982.

- Cline, Howard F.. The United States and Mexico. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1953.

- De Parodi, Enriqueta. Abelardo L. Rodríguez: Estadista y benefactor. Mexico City: Gráfica Panamericana, S. de R.L. 1957.

- Dulles, John W. F., Yesterday in Mexico: A Chronicle of the Revolution, 1919-1936. Austin: University of Texas Press 1961.

- Durante de Cabarga, Guillermo. Abelardo L. Rodríguez: El hombre de la hora. Mexico City: Ediciones Botas 1933.

- Feller, A.H. The Mexican Claims Commissions, 1923-34. New York: Macmillan 1935.

- Gaxiola, Francisco Javier Jr. El Presidente Rodríguez. Cultura 1938.

- Krauze, Enrique, Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins 1997. ISBN 0-06-016325-9

- Memoria administrativa del gobierno del Distrito Norte de la Baja California 1924-1927, Abelardo L. Rodríguez

- Rodríguez, Abelardo L. Autobiografía

- Uribe Romo, Emilio. Abelardo L. Rodríguez: De San José de Guaymas al Castillo de Chapultepec; Del Plan de Guadalupe al Plan Sexenal. Mexico City: Talleres Gráficos de la Nación 1934.

External links

- English biography. Accessed April 16, 2005.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Pascual Ortiz |

President of Mexico 1932–1934 |

Succeeded by Lázaro Cárdenas |