Abortion in South Carolina

Abortion in South Carolina is legal. 42% of adults said in a poll by the Pew Research Center that abortion should be legal in all or most cases.

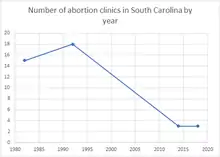

The number of abortion clinics in South Carolina has fluctuated over the years, with fifteen in 1982, eighteen in 1992 and three in 2014. There were 5,714 legal abortions in 2014, and 5,778 in 2015.

Terminology

The abortion debate most commonly relates to the "induced abortion" of an embryo or fetus at some point in a pregnancy, which is also how the term is used in a legal sense.[note 1] Some also use the term "elective abortion", which is used in relation to a claim to an unrestricted right of a woman to an abortion, whether or not she chooses to have one. The term elective abortion or voluntary abortion describes the interruption of pregnancy before viability at the request of the woman, but not for medical reasons.[1]

Anti-abortion advocates tend to use terms such as "unborn baby", "unborn child", or "pre-born child",[2][3] and see the medical terms "embryo", "zygote", and "fetus" as dehumanizing.[4][5] Both "pro-choice" and "pro-life" are examples of terms labeled as political framing: they are terms which purposely try to define their philosophies in the best possible light, while by definition attempting to describe their opposition in the worst possible light. "Pro-choice" implies that the alternative viewpoint is "anti-choice", while "pro-life" implies the alternative viewpoint is "pro-death" or "anti-life".[6] The Associated Press encourages journalists to use the terms "abortion rights" and "anti-abortion".[7]

Context

Free birth control correlates to teenage girls having a fewer pregnancies and fewer abortions. A 2014 New England Journal of Medicine study found such a link. At the same time, a 2011 study by Center for Reproductive Rights and Ibis Reproductive Health also found that states with more abortion restrictions have higher rates of maternal death, higher rates of uninsured pregnant women, higher rates of infant and child deaths, higher rates of teen drug and alcohol abuse, and lower rates of cancer screening.[8]

According to a 2017 report from the Center for Reproductive Rights and Ibis Reproductive Health, states that tried to pass additional constraints on a women's ability to access legal abortions had fewer policies supporting women's health, maternal health and children's health. These states also tended to resist expanding Medicaid, family leave, medical leave, and sex education in public schools.[9] According to Megan Donovan, a senior policy manager at the Guttmacher Institute, states have legislation seeking to protect a woman's right to access abortion services have the lowest rates of infant mortality in the United States.[9]

Poor women in the United States had problems paying for menstrual pads and tampons in 2018 and 2019. Almost two-thirds of American women could not pay for them. These were not available through the federal Women, Infants, and Children Program (WIC).[10] Lack of menstrual supplies has an economic impact on poor women. A study in St. Louis found that 36% had to miss days of work because they lacked adequate menstrual hygiene supplies during their period. This was on top of the fact that many had other menstrual issues including bleeding, cramps and other menstrual induced health issues.[10] This state was one of a majority that taxed essential hygiene products like tampons and menstrual pads as of November 2018.[11][12][13][14]

History

South Carolinian women have a long history of traveling outside the state to seek legal abortions. Critics of efforts by state lawmakers to restrict abortion access say it results in South Carolinian women needing to spend more money and travel greater distances for the procedure.[15]

Legislative history

By the end of the 1800s, all states in the Union except Louisiana had therapeutic exceptions in their legislative bans on abortions.[16] In the 19th century, bans by state legislatures on abortion were about protecting the life of the mother given the number of deaths caused by abortions; state governments saw themselves as looking out for the lives of their citizens.[16] By 1950, the state legislature would pass a law that stating that a woman who had an abortion or actively sought to have an abortion regardless of whether she went through with it were guilty of a criminal offense.[16]

The state was one of 23 states in 2007 to have a detailed abortion-specific informed consent requirement.[17] In 2013, state Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers (TRAP) law applied to medication induced abortions and private doctor offices in addition to abortion clinics.[18] Governor Nikki Haley signed legislation that brought into effect a 20-week abortion ban in 2016. At a ceremonial signing ceremony for the cameras, she was surrounded by children with disabilities.[15]

Republican Representative Greg Delleney was the lead sponsor of South Carolina's law requiring that women view an ultrasound of a fetus before being allowed to have an abortion. He said the ultrasound would enable the woman to "determine for herself whether she is carrying an unborn child deserving of protection or whether it's just an inconvenient, unnecessary part of her body." [19] Rep. John Mccravy prefiled HB 3020 in the South Carolina House of Representatives in December 2018.[20] The bill, which is entitled "Fetal Heartbeat Protection from Abortion Act", was introduced on January 8, 2018 and referred to the House Judiciary Committee.[21][22] Previous attempts to pass fetal heartbeat bills in the South Carolina General Assembly have failed.[23][24] The state legislature was one of ten states nationwide that to pass similar legislation that year.[25]

[24] In April 2019, by a vote of 70–31, the S.C. House of Representatives passed a "fetal heartbeat" bill. The measure passed after five hours of debate.[26]

Judicial history

The US Supreme Court's decision in 1973's Roe v. Wade ruling meant the state could no longer regulate abortion in the first trimester.[16] The US Supreme Court heard Ferguson v. City of Charleston in 2001.[27] On appeal, the Fourth Circuit affirmed, but on the ground that the searches were justified as a matter of law by special non-law-enforcement needs.[28] The Supreme Court had a 6 - 3 ruling in a case about a South Carolina public hospital policy requiring all pregnant women to be drug tested. The Supreme Court ruled that the US Constitution's Fourth Amendment protected women against unreasonable search and seizures, which mandatory drug testing was.[27] The US Supreme Court reasoned that the interest in curtailing pregnancy complications and reducing the medical costs associated with maternal cocaine use outweighed what it characterized as a "minimal intrusion" on the women's privacy. The Supreme Court then agreed to hear the case.[29] Justice Kennedy pointed out that all searches, by definition, would uncover evidence of crime, and this says nothing about the "special needs" the search might serve. In this case, however, Kennedy agreed that "while the policy may well have served legitimate needs unrelated to law enforcement, it had as well a penal character with a far greater connection to law enforcement than other searches sustained under our special needs rationale."[30]

Clinic history

Between 1982 and 1992, the number of abortion clinics in the state increased by three, going from fifteen in 1982 to eighteen in 1992.[31] In 2014, there were three abortion clinics in the state.[32] In 2014, 93% of the counties in the state did not have an abortion clinic. That year, 71% of women in the state aged 15 – 44 lived in a county without an abortion clinic.[33] In 2017, there were two Planned Parenthood clinics in a state with a population of 1,112,199 women aged 15 – 49 of which one offered abortion services.[34] In 2018, there were three licensed abortion clinics in the state. They were in Charleston, Columbia and Greenville.[15] The Charleston clinic was a Planned Parenthood clinic in West Ashley.[15]

Statistics

In the period between 1972 and 1974, the state had an illegal abortion mortality rate per million women aged 15–44 of between 0.1 and 0.9.[35] In 1990, 411,000 women in the state faced the risk of an unintended pregnancy.[31] There were around 5,600 women in the South Carolina in 1995 left the state to get an abortion.[15] There were around 8,801 abortions performed in South Carolina in 1998.[15]

In 2010, the state had nine publicly funded abortions, of which were nine federally funded and zero were state funded.[36] In 2013, among white women aged 15–19, there were abortions 660, 620 abortions for black women aged 15–19, 60 abortions for Hispanic women aged 15–19, and 40 abortions for women of all other races.[37] In 2014, 42% of adults said in a poll by the Pew Research Center that abortion should be legal in all or most cases.[38] There were around 5,600 women in the South Carolina in 2015 left the state to get an abortion. This number was one of the highest in the United States.[15] Only 5.9% of abortions performed in the state involved out-of-state residents in 2015. This contrasted with neighboring North Carolina and Georgia. 14.5% of all abortions in Georgia that year were for out-of-state residents, while 7.5% of all abortions performed in North Carolina were performed for out-of-state residents. [15] There were around 11,000 abortions performed in South Carolina in 2017.[15] That year, South Carolina had an infant mortality rate of 6.5 deaths per 1,000 live births.[9]

| Census division and state | Number | Rate | % change 1992–1996 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 1995 | 1996 | 1992 | 1995 | 1996 | ||

| South Atlantic | 269,200 | 261,990 | 263,600 | 25.9 | 24.6 | 24.7 | –5 |

| Delaware | 5,730 | 5,790 | 4,090 | 35.2 | 34.4 | 24.1 | –32 |

| District of Columbia | 21,320 | 21,090 | 20,790 | 138.4 | 151.7 | 154.5 | 12 |

| Florida | 84,680 | 87,500 | 94,050 | 30 | 30 | 32 | 7 |

| Georgia | 39,680 | 36,940 | 37,320 | 24 | 21.2 | 21.1 | –12 |

| Maryland | 31,260 | 30,520 | 31,310 | 26.4 | 25.6 | 26.3 | 0 |

| North Carolina | 36,180 | 34,600 | 33,550 | 22.4 | 21 | 20.2 | –10 |

| South Carolina | 12,190 | 11,020 | 9,940 | 14.2 | 12.9 | 11.6 | –19 |

| Virginia | 35,020 | 31,480 | 29,940 | 22.7 | 20 | 18.9 | –16 |

| West Virginia | 3,140 | 3,050 | 2,610 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 6.6 | –14 |

| Location | Residence | Occurrence | % obtained by

out-of-state residents |

Year | Ref | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Rate^ | Ratio^^ | No. | Rate^ | Ratio^^ | ||||

| South Carolina | 9,774 | 10.4 | 170 | 5,714 | 6.1 | 99 | 5.3 | 2014 | [40] |

| South Carolina | 11,032 | 11.6 | 190 | 5,778 | 6.1 | 99 | 5.9 | 2015 | [41] |

| South Carolina | 10,773 | 11,2 | 188 | 5,736 | 6.0 | 100 | 5.4 | 2016 | [42] |

| ^number of abortions per 1,000 women aged 15–44; ^^number of abortions per 1,000 live births | |||||||||

Abortion rights views and activities

Protests

Women from the state participated in marches supporting abortion rights as part of a #StoptheBans movement in May 2019.[43]

Anti-abortion rights views and activities

Views

Between 1998 and 2017, the number of abortions that took place on a yearly basis in the state dropped by 5,112. According to anti-abortion rights group South Carolina Citizens for Life this drop meant that harsh anti-abortion measures in the state worked. According to South Carolina Citizens Executive Director Holly Gatling in regards to the number of women seeking abortions outside the state over the same period remaining unchanged, "South Carolina Citizens for Life is responsible for South Carolina, not for any other state where women who claim to be from South Carolina abort their children. [...] All we can do is work to reduce the number of abortions occurring in South Carolina, and we have done that and continue to do so."[15]

Governor Nikki Haley said in 2016, "I'm not pro-life because the Republican Party tells me. [...] I'm pro-life because all of us have had experiences of what it means to have one of these special little ones in our life."[15]

Charleston Republican Senator Larry Grooms said in 2018, "I believe that all life is sacred, that an unborn child has a right to life, just like a child that has already experienced birth."[15]

South Carolina state Rep. Nancy Mace said during the sex-week "fetal heartbeat" in 2019 on the floor of the House during a 10-minute floor speech about an amendment she introduced, "I was gripping the podium so hard I thought I was going to pull it out of the floor. [...] I was angry at the language my colleagues were using. They were saying rape was the fault of the woman. They called these women baby killers and murderers. That language is so degrading toward women, particularly victims of rape or incest. And I said to myself I'm not going to put up with that bull----. I was nearly yelling into the mic. I gave a very passionate speech to my colleagues and that is what got the exception through."[44]

Footnotes

- According to the Supreme Court's decision in Roe v. Wade:

(a) For the stage prior to approximately the end of the first trimester, the abortion decision and its effectuation must be left to the medical judgement of the pregnant woman's attending physician. (b) For the stage subsequent to approximately the end of the first trimester, the State, in promoting its interest in the health of the mother, may, if it chooses, regulate the abortion procedure in ways that are reasonably related to maternal health. (c) For the stage subsequent to viability, the State in promoting its interest in the potentiality of human life may, if it chooses, regulate, and even proscribe, abortion except where it is necessary, in appropriate medical judgement, for the preservation of the life or health of the mother.

Likewise, Black's Law Dictionary defines abortion as "knowing destruction" or "intentional expulsion or removal".

References

- Watson, Katie (20 Dec 2019). "Why We Should Stop Using the Term "Elective Abortion"". AMA Journal of Ethics. 20: E1175-1180. doi:10.1001/amajethics.2018.1175. PMID 30585581. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- Chamberlain, Pam; Hardisty, Jean (2007). "The Importance of the Political 'Framing' of Abortion". The Public Eye Magazine. 14 (1).

- "The Roberts Court Takes on Abortion". New York Times. November 5, 2006. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- Brennan 'Dehumanizing the vulnerable' 2000

- Getek, Kathryn; Cunningham, Mark (February 1996). "A Sheep in Wolf's Clothing – Language and the Abortion Debate". Princeton Progressive Review.

- "Example of "anti-life" terminology" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- Goldstein, Norm, ed. The Associated Press Stylebook. Philadelphia: Basic Books, 2007.

- Castillo, Stephanie (2014-10-03). "States With More Abortion Restrictions Hurt Women's Health, Increase Risk For Maternal Death". Medical Daily. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- "States pushing abortion bans have highest infant mortality rates". NBC News. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- Mundell, E.J. (January 16, 2019). "Two-Thirds of Poor U.S. Women Can't Afford Menstrual Pads, Tampons: Study". US News & World Report. Retrieved May 26, 2019.

- Larimer, Sarah (January 8, 2016). "The 'tampon tax,' explained". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- Bowerman, Mary (July 25, 2016). "The 'tampon tax' and what it means for you". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- Hillin, Taryn. "These are the U.S. states that tax women for having periods". Splinter. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- "Election Results 2018: Nevada Ballot Questions 1-6". KNTV. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- lsausser@postandcourier.com, Lauren Sausser. "As national abortion rate drops, SC women increasingly terminate pregnancies elsewhere". Post and Courier. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- Buell, Samuel (1991-01-01). "Criminal Abortion Revisited". New York University Law Review. 66: 1774–1831.

- "State Policy On Informed Consent for Abortion" (PDF). Guttmacher Policy Review. Fall 2007. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- "TRAP Laws Gain Political Traction While Abortion Clinics—and the Women They Serve—Pay the Price". Guttmacher Institute. 2013-06-27. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- "State Abortion Counseling Policies and the Fundamental Principles of Informed Consent". Guttmacher Institute. 2007-11-12. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- "SC - 123rd General Assembly - House Bill 3020". LegisScan. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- "SC - 123rd General Assembly - House Bill 3020". LegisScan. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- "State legislatures see flurry of activity on abortion bills". PBS NewsHour. 2018-02-03. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- "SC - 122nd General Assembly - House Bill 5403". LegiScan. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- Tavernise, Sabrina (2019-05-15). "'The Time Is Now': States Are Rushing to Restrict Abortion, or to Protect It". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- Lai, K. K. Rebecca (2019-05-15). "Abortion Bans: 8 States Have Passed Bills to Limit the Procedure This Year". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- By. "SC House passes 6-week 'fetal heartbeat' abortion ban". thestate. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- "Timeline of Important Reproductive Freedom Cases Decided by the Supreme Court". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- Ferguson v. City of Charleston, 186 F.3d 469 (4th Cir. 1999).

- Ferguson v. City of Charleston, 528 U.S. 1187 (2000).

- Ferguson, 532 U.S. at 88-89 (Kennedy, J., concurring in the judgment).

- Arndorfer, Elizabeth; Michael, Jodi; Moskowitz, Laura; Grant, Juli A.; Siebel, Liza (December 1998). A State-By-State Review of Abortion and Reproductive Rights. Diane Publishing. ISBN 9780788174810.

- Gould, Rebecca Harrington, Skye. "The number of abortion clinics in the US has plunged in the last decade — here's how many are in each state". Business Insider. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- businessinsider (2018-08-04). "This is what could happen if Roe v. Wade fell". Business Insider (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- "Here's Where Women Have Less Access to Planned Parenthood". Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- Cates, Willard; Rochat, Roger (March 1976). "Illegal Abortions in the United States: 1972–1974". Family Planning Perspectives. 8 (2): 86. doi:10.2307/2133995. JSTOR 2133995. PMID 1269687.

- "Guttmacher Data Center". data.guttmacher.org. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- "No. of abortions among women aged 15–19, by state of residence, 2013 by racial group". Guttmacher Data Center. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- "Views about abortion by state - Religion in America: U.S. Religious Data, Demographics and Statistics". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- "Abortion Incidence and Services in the United States, 1995-1996". Guttmacher Institute. 2005-06-15. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- Jatlaoui, Tara C. (2017). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2014". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 66 (24): 1–48. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6624a1. ISSN 1546-0738. PMID 29166366.

- Jatlaoui, Tara C. (2018). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2015". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 67 (13): 1–45. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6713a1. ISSN 1546-0738. PMC 6289084. PMID 30462632.

- Jatlaoui, Tara C. (2019). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2016". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 68. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6811a1. ISSN 1546-0738.

- Bacon, John. "Abortion rights supporters' voices thunder at #StopTheBans rallies across the nation". USA Today. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- "When it comes to abortion, conservative women aren't a monolith". USA Today. Retrieved 2019-05-26.