Achilles tendinitis

Achilles tendinitis, also known as achilles tendinopathy, occurs when the Achilles tendon, found at the back of the ankle, becomes sore. Achilles tendinopathy is accompanied by alterations in the tendon’s structure and mechanical properties.[2] The most common symptoms are pain and swelling around the affected tendon.[1] The pain is typically worse at the start of exercise and decreases thereafter.[3] Stiffness of the ankle may also be present.[2] Onset is generally gradual.[1]

| Achilles tendinitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Achilles tendinopathy, Achilles tendonitis, Achilles tenosynovitis |

| |

| Drawing of Achilles tendonitis with the affected part highlighted in red | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

| Symptoms | Pain, swelling around the affected tendon[1] |

| Usual onset | Gradual[1] |

| Duration | Months[2] |

| Types | Noninsertional, insertional[2] |

| Causes | Overuse[2] |

| Risk factors | Trauma, lifestyle that includes little exercise, high-heel shoes, rheumatoid arthritis, medications of the fluoroquinolone or steroid class[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and examination[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Achilles tendon rupture[3] |

| Treatment | Rest, ice, non-steroidal antiinflammatory agents (NSAIDs), physical therapy[1][2] |

| Frequency | Common[2] |

It commonly occurs as a result of overuse such as running.[2][3] Other risk factors include trauma, a lifestyle that includes little exercise, high-heel shoes, rheumatoid arthritis, and medications of the fluoroquinolone or steroid class.[1] Diagnosis is generally based on symptoms and examination.[3]

There are several simple actions that individuals can take to prevent or reduce tendinitis. Though commonly used, some of these actions have limited or no scientific evidence to support them, namely pre-exercise stretching. Strengthening calf muscles, avoiding over-training, and selecting more appropriate footwear are more well-regarded options.[4][5][6] Running mechanics can be improved with simple exercises that will help runners avoid achilles injury.[7] Treatment typically involves rest, ice, non-steroidal antiinflammatory agents (NSAIDs), and physical therapy.[1][2] A heel lift or orthotics may also be helpful.[2][3] In those whose symptoms last more than six months despite other treatments, surgery may be considered.[2] Achilles tendinitis is relatively common.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms can vary from an ache or pain and swelling to the local area of the ankles, or a burning that surrounds the whole joint. With this condition, the pain is usually worse during and after activity, and the tendon and joint area can become stiffer the following day as swelling impinges on the movement of the tendon. Many patients report stressful situations in their lives in correlation with the beginnings of pain which may contribute to the symptoms.

Achilles tendon injuries can be separated into insertional tendinopathy (20%–25% of the injuries), midportion tendinopathy (55%–65%), and proximal musculotendinous junction (9%–25%) injuries, according to the location of pain. [8]

Cause

Achilles tendinitis is a common injury, particularly in sports that involve lunging and jumping. It is also a known side effect of fluoroquinolone antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin, as are other types of tendinitis.[9]

Swelling in a region of micro-damage or partial tear can be detected visually or by touch. Increased water content and disorganized collagen matrix in tendon lesions may be detected by ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging.

Achilles tendinitis is thought to have physiological, mechanical, or extrinsic (i.e. footwear or training) causes. Physiologically, the Achilles tendon is subject to poor blood supply through the synovial sheaths that surround it. This lack of blood supply can lead to the degradation of collagen fibers and inflammation.[10] Tightness in the calf muscles has also been known to be involved in the onset of Achilles tendinitis.[11]

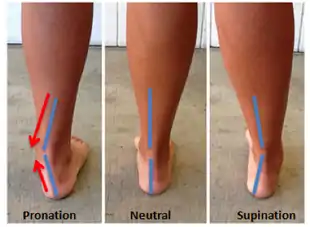

During the loading phase of the running and walking cycle, the ankle and foot naturally pronate and supinate by approximately 5 degrees.[12] Excessive pronation of the foot (over 5 degrees) in the subtalar joint is a type of mechanical mechanism that can lead to tendinitis.[11][12]

An overuse injury refers to repeated stress and strain, which is likely the case in endurance runners.[13][14] Overuse can simply mean an increase in running, jumping or plyometric exercise intensity too soon. Another consideration would be the use of improper or worn-down footwear, which lack the necessary support to maintain the foot in the natural/normal pronation.[14]

Pathophysiology

The Achilles tendon is the extension of the calf muscle and attaches to the heel bone. It causes the foot to extend (plantar flexion) when those muscles contract.

The Achilles tendon does not have good blood supply or cell activity, so this injury can be slow to heal. The tendon receives nutrients from the tendon sheath or paratendon. When an injury occurs to the tendon, cells from surrounding structures migrate into the tendon to assist in repair. Some of these cells come from blood vessels that enter the tendon to provide direct blood flow to increase healing. With the blood vessels come nerve fibers. Researchers including Alfredson and his team in Sweden [15] believe these nerve fibers to be the cause of the pain - they injected local anaesthetic around the vessels and this decreased significantly the pain from the Achilles tendon.

Diagnosis

.jpg.webp)

Achilles tendinitis is usually diagnosed from a medical history, and physical examination of the tendon. Projectional radiography shows calcification deposits within the tendon at its calcaneal insertion in approximately 60 percent of cases.[16] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can determine the extent of tendon degeneration, and may show differential diagnoses such as bursitis.[16]

Prevention

Performing consistent physical activity will improve the elasticity and strength of the tendon, which will assist in resisting the forces that are applied.[18]

While stretching before beginning an exercise session is often recommended evidence to support this practice is limited.[4][5] Prevention of recurrence includes following appropriate exercise habits and wearing low-heeled shoes. In the case of incorrect foot alignment, orthotics can be used to properly position the feet.[18] Footwear that is specialized to provide shock-absorption can be utilized to defend the longevity of the tendon.[19] Achilles tendon injuries can be the result of exceeding the tendon's capabilities for loading, therefore it is important to gradually adapt to exercise if someone is inexperienced, sedentary, or is an athlete who is not progressing at a steady rate.[19]

Eccentric strengthening exercises of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles are utilized to improve the tensile strength of the tendon and lengthen the muscle-tendon junction, decreasing the amount of strain experienced with ankle joint movements.[20] This eccentric training method is especially important for individuals with chronic Achilles tendinosis which is classified as the degeneration of collagen fibers.[19] These involve repetitions of slowly lowering the body while standing on the affected leg, using the opposite arm and foot to assist in repeating the cycle, and starting with the heel in a hyperextended position. (Hyperextension is typically achieved by balancing the forefoot on the edge of a step, a thick book, or a barbell weight so that the point of the heel is a couple of inches above the forefoot.)

Treatment

Treatment typically involves rest, ice, non-steroidal antiinflammatory agents (NSAIDs), and physical therapy.[1][2] A heel lift or orthotics may also be helpful.[3][2]

- An eccentric exercise routine designed to strengthen the tendon.

- Application of a boot or cast.

Injections

The evidence to support injection therapies is poor.[21]

- This includes corticosteroid injections.[1] These can also increase the risk of tendon rupture.[21]

- Autologous blood injections - results have not been highly encouraging and there is little evidence for their use.[22][23][1]

Procedures

Tentative evidence supports the use of extracorporeal shockwave therapy.[24]

Exercise Rehabilitation

The treatment with the highest level of evidence for Achilles Tendinopathy is exercise rehabilitation. The following information is an example Exercise Rehabilitation program from the Clinical Practice Guidelines, "Achilles Pain, Stiffness, and Muscle Power Deficits: Midportion Achilles Tendinopathy Revision 2018"[25] Heavy-load, slow-speed full range of motion hell raise exercises, performed at a speed of 6 seconds per repetition are encouraged.

Example exercises include:

- Seated calf-raise machine

- Heel raises with a barbell on shoulders

- Heel raises on a leg-press machine

Treatment should include a 12-week program which increases the resistance progressively.

- Week 1: 3 sets of 5 repetitions

- Week 2 & 3: 3 sets of 12 repetitions

- Week 4 & 5: 4 sets of 10 repetitions

- Week 6, 7 & 8: 4 sets of 8 repetitions

- Week 9, 10, 11 & 12: 4 sets of 6 repetitions

Epidemiology

The prevalence of Achilles tendinitis varies among different ages and groups of people. Achilles tendinitis is most commonly found in individuals aged 30–40[26] Runners are susceptible,[26] as well as anyone participating in sports, and men aged 30–39.[27]

Risk factors include participating in a sport or activity that involves running, jumping, bounding, and change of speed. Although Achilles tendinitis is mostly likely to occur in runners, it also is more likely in participants in basketball, volleyball, dancing, gymnastics and other athletic activities.[26] Other risk factors include gender, age, improper stretching, and overuse.[28] Another risk factor is any congenital condition in which an individual's legs rotate abnormally, which in turn causes the lower extremities to overstretch and contract; this puts stress on the Achilles tendon and will eventually cause Achilles tendinitis.[28]

References

- Hubbard, MJ; Hildebrand, BA; Battafarano, MM; Battafarano, DF (June 2018). "Common Soft Tissue Musculoskeletal Pain Disorders". Primary Care. 45 (2): 289–303. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2018.02.006. PMID 29759125.

- Silbernagel, Karin (2020). [10.4085/1062-6050-356-19 "Current Clinical Concepts: Conservative Management of Achilles Tendinopathy"] Check

|url=value (help). Journal of Athletic Training. 55: 0–0000 – via www.natajournals.org. line feed character in|title=at position 51 (help) - "Achilles Tendinitis". MSD Manual Professional Edition. March 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- Park, DY; Chou, L (December 2006). "Stretching for prevention of Achilles tendon injuries: a review of the literature". Foot & Ankle International. 27 (12): 1086–95. doi:10.1177/107110070602701215. PMID 17207437.

- Peters, JA; Zwerver, J; Diercks, RL; Elferink-Gemser, MT; van den Akker-Scheek, I (March 2016). "Preventive interventions for tendinopathy: A systematic review". Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 19 (3): 205–211. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2015.03.008. PMID 25981200.

- "Achilles tendinitis - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- https://www.runnersworld.com/uk/news/a30105915/avoid-achilles-injuries-exercises/

- Kvist, M (1991). "Achilles tendon injuries in athletes". Ann Chir Gynaecol. 80: 188–201.

- "FDA orders 'black box' label on some antibiotics". CNN. 8 July 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- Fenwick S. A.; Hazleman B. L.; Riley G. P. (2002). "The vasculature and its role in the damaged and healing tendon". Arthritis Research. 4 (4): 252–260. doi:10.1186/ar416. PMC 128932. PMID 12106496.

- Maffulli N.; Sharma P.; Luscombe K. L. (2004). "Achilles tendinopathy: aetiology and management". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 97 (10): 472–476. doi:10.1258/jrsm.97.10.472. PMC 1079614. PMID 15459257.

- Hintermann B., Nigg B. M. (1998). "Pronation in runners". Sports Medicine. 26 (3): 169–176. doi:10.2165/00007256-199826030-00003. PMID 9802173.

- Kannus P (1997). "Etiology and pathophysiology of chronic tendon disorders in sports". Scandinavian Journal of Sports Medicine. 7 (2): 78–85. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.1997.tb00123.x. PMID 9211608.

- McCrory J. L.; Martin D. F.; Lowery R. B.; Cannon D. W.; Curl W. W.; Read Jr H. M.; Hunter D.M.; Craven T.; Messier S. P. (1999). "Etiologic factors associated with Achilles tendinitis in runners". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 31 (10): 1374–1381. doi:10.1097/00005768-199910000-00003. PMID 10527307. S2CID 25204643.

- Alfredson, H.; Ohberg, L.; Forsgren, S. (Sep 2003). "Is vasculo-neural ingrowth the cause of pain in chronic Achilles tendinosis? An investigation using ultrasonography and colour Doppler, immunohistochemistry, and diagnostic injections". Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 11 (5): 334–8. doi:10.1007/s00167-003-0391-6. PMID 14520512.

- "Insertional Achilles Tendinitis". American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society. Retrieved 2017-01-17.

- Floyd, R.T. (2009). Manual of Structural Kinesiology. New York, NY: McGraw Hill

- Hess G.W. (2009). "Achilles Tendon Rupture: A Review of Etiology, Population, Anatomy, Risk Factors, and Injury Prevention". Foot & Ankle Specialist. 3 (1): 29–32. doi:10.1177/1938640009355191. PMID 20400437.

- Alfredson H., Lorentzon R. (2012). "Chronic Achilles Tendinosis: Recommendations for Treatment and Prevention". Sports Medicine. 29 (2): 135–146. doi:10.2165/00007256-200029020-00005. PMID 10701715.

- G T Allison, C Purdam. Eccentric loading for Achilles tendinopathy — strengthening or stretching? Br J Sports Med 2009;43:276-279

- Kearney, RS; Parsons, N; Metcalfe, D; Costa, ML (26 May 2015). "Injection therapies for Achilles tendinopathy" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD010960. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010960.pub2. PMID 26009861.

- "JBJS | Limited Evidence Supports the Effectiveness of Autologous Blood Injections for Chronic Tendinopathies". jbjs.org. 2012. Archived from the original on March 29, 2012. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- de Vos RJ, van Veldhoven PL, Moen MH, Weir A, Tol JL, Maffulli N (2012). "Autologous growth factor injections in chronic tendinopathy: a systematic review". bmb.oxfordjournals.org. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- Korakakis, V; Whiteley, R; Tzavara, A; Malliaropoulos, N (March 2018). "The effectiveness of extracorporeal shockwave therapy in common lower limb conditions: a systematic review including quantification of patient-rated pain reduction". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 52 (6): 387–407. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-097347. PMID 28954794.

- MARTIN, ROBROY (2018). "Clinical Practice Guidelines: Achilles Pain, Stiffness, and Muscle Power Deficits: Midportion Achilles Tendinopathy Revision 2018". Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 48.

- Leach R. E.; James S.; Wasilewski S. (1981). "Achilles tendinitis". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 9 (2): 93–98. doi:10.1177/036354658100900204. PMID 7223927.

- Leppilant J.; Puranen J.; Orava S. (1996). "Incidence of Achilles Tendon Injury". Acta Orthopaedica. 67 (3): 277–79. doi:10.3109/17453679608994688. PMID 8686468.

- Kainberger, F; Fialka, V; Breitenseher, M; Kritz, H; Baldt, M; Czerny, C; Imhof, H (1996). "Differential diagnosis of diseases of the Achilles tendon. A clinico-sonographic concept". Der Radiologe. 36 (1): 38–46. doi:10.1007/s001170050037. PMID 8820370.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |