Synovial membrane

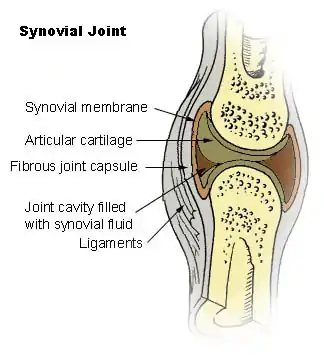

The synovial membrane (also known as the synovial stratum, synovium or stratum synoviale) is a specialized connective tissue that lines the inner surface of capsules of synovial joints and tendon sheath.[1] It makes direct contact with the fibrous membrane on the outside surface and with the synovial fluid lubricant on the inside surface. In contact with the synovial fluid at the tissue surface are many rounded macrophage-like synovial cells (type A) and also type B cells, which are also known as fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS). Type A cells maintain the synovial fluid by removing wear-and-tear debris. As for the FLS, they produce hyaluronan, as well as other extracellular components in the synovial fluid.[2]

| Synovial membrane | |

|---|---|

Typical Joint | |

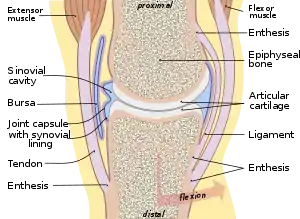

Synovial joint | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | membrana synovialis capsulae articularis |

| MeSH | D013583 |

| TA98 | A03.0.00.028 |

| TA2 | 1538 |

| FMA | 66762 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

The synovial membrane is variable but often has two layers

- The outer layer, or subintima, can be of almost any type of connective tissue – fibrous (dense collagenous type), adipose (fatty; e.g. in intra-articular fat pads) or areolar (loose collagenous type).

- The inner layer (in contact with synovial fluid), or intima, consists of a sheet of cells thinner than a piece of paper.

Where the underlying subintima is loose, the intima sits on a pliable membrane, giving rise to the term synovial membrane.

This membrane, together with the cells of the intima, provides something like an inner tube, sealing the synovial fluid from the surrounding tissue (effectively stopping the joints from being squeezed dry when subject to impact, such as running).

Just beneath the intima, most synovium has a dense net of fenestrated small blood vessels that provide nutrients not only for synovium but also for the avascular cartilage.

In any one position, much of the cartilage is close enough to get nutrition directly from the synovium.

Some areas of cartilage have to obtain nutrients indirectly and may do so either from diffusion through cartilage or possibly by 'stirring' of synovial fluid.

The surface of synovium may be flat or may be covered with finger-like projections or villi, which, it is presumed, help to allow the soft tissue to change shape as the joint surfaces move one on another.

The synovial fluid can be thought of as a specialised fluid form of synovial extracellular matrix rather than a secretion in the usual sense.[1] The fluid is transudative in nature which facilitates continuous exchange of oxygen, carbon dioxide and metabolites between blood and synovial fluid.[1] This is especially important since it is the major source of metabolic support for articular cartilage.[1] Under normal conditions synovial fluid contain <100/mL of leucocytes in which majority are monocytes.[1]

Synovial cells

The intimal cells are of two types, fibroblast-like synoviocytes or type B cells and macrophage-like synovial cells. Surface cells have no basement membrane or junctional complexes denoting an epithelium despite superficial resemblance.

- The fibroblast-like synoviocytes (derived from mesenchyme)[2] manufacture a long-chain sugar polymer called hyaluronan (hence rich in endoplasmic reticulum); which makes the synovial fluid "ropy"-like egg-white, together with a molecule called lubricin, which lubricates the joint surfaces. The water of synovial fluid is not secreted as such but is effectively trapped in the joint space by the hyaluronan.

- The macrophage-like synovial cells (derived from monocytes in blood)[2] are responsible for the removal of undesirable substances from the synovial fluid (hence are rich in Golgi apparatus). It accounts for approximately 25% of cells lining the synovium.

| Synovial cell | Resemble | Prominent organelle | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type A | Macrophage | Mitochondria | Phagocytosis |

| Type B | Fibroblast | Endoplasmic reticulum | Secrete hyaluronic acid, & proteins complex (mucin) of synovial fluid |

Mechanics

Although a biological joint can resemble a man-made joint in being a hinge or a ball and socket, the engineering problems that nature must solve are very different because the joint works within an almost completely solid structure, with no wheels or nuts and bolts.

In general, the bearing surfaces of manmade joints interlock, as in a hinge. This is rare for biological joints (although the badger's jaw interlocks).

More often the surfaces are held together by cord-like ligaments. Virtually all the space between muscles, ligaments, bones, and cartilage is filled with pliable solid tissue. The fluid-filled gap is at most only a twentieth of a millimetre thick. This means that synovium has certain rather unexpected jobs to do. These may include:

- Providing a plane of separation, or disconnection, between solid tissues so that movement can occur with minimum bending of solid components. If this separation is lost, as in a 'frozen shoulder', the joint cannot move.

- Providing a packing that can change shape in whatever way is needed to allow the bearing surfaces to move on each other.

- Controlling the volume of fluid in the cavity so that it is just enough to allow the solid components to move over each other freely. This volume is normally so small that the joint is under slight suction.

Pathology

Synovium can become irritated and thickened (synovitis) in conditions such as osteoarthritis,[3] Ross River virus[4] or rheumatoid arthritis (RA).[5] The fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) play a key role in the pathogenesis of RA, and the aggressive phenotype of FLS in RA and the effect these cells have on the microenvironment in the joint can be summarized into hallmarks that distinguish them from healthy FLS. These hallmark features of FLS in RA are divided into 7 cell-intrinsic hallmarks (such as reduced apoptosis and impaired contact inhibition) and 4 cell-extrinsic hallmarks (such as their ability to recruit and stimulate immune cells).[6]

In general, inflamed synovium is accompanied by extra macrophage recruitment (as well as the existing type A cells), fibroblast proliferation and an influx of inflammatory cells including lymphocytes, monocytes and plasma cells.[7] When this happens, the synovium can interfere with the normal functioning of the joint. Excessive thickened synovium, filled with cells and fibrotic collagenous tissue, can physically restrict joint movement. The synovial fibroblasts may make smaller hyaluronan so it is a less effective lubricant of the cartilage surfaces. Under stimulation from invading inflammatory cells, the synovial cells may also produce enzymes (proteinases) that can digest the cartilage extracellular matrix. Fragments of extracellular matrix can then further irritate the synovium.

Etymology and pronunciation

The word synovium is related to the word synovia in its sense meaning "synovial fluid". The latter was coined by Paracelsus.[8] More information is given at Synovial fluid § Etymology and pronunciation.

See also

References

- Young, Barbara; Lowe, James S.; Stevens, Alan; Heath, John W.; Deakin, Philip J. (2006). Wheater's Functional Histology: A Text and Colour Atlas (5th ed.). Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 9780443068508.

- Junqueira's Basic Histology: Text and Atlas (13th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education / Medical. 2013-02-13. ISBN 9780071780339.

- Man GS, Mologhianu G (2014). "Osteoarthritis pathogenesis - a complex process that involves the entire joint". J. Med. Life. 7 (1): 37–41. PMC 3956093. PMID 24653755.

- Suhrbier A, La Linn M (2004). "Clinical and pathologic aspects of arthritis due to Ross River virus and other alphaviruses". Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 16 (4): 374–9. doi:10.1097/01.bor.0000130537.76808.26. PMID 15201600.

- Townsend MJ (2014). "Molecular and cellular heterogeneity in the Rheumatoid Arthritis synovium: clinical correlates of synovitis". Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 28 (4): 539–49. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2014.10.024. PMID 25481548.

- Nygaard, G.; Firestein, G. S. (2020). "Restoring synovial homeostasis in rheumatoid arthritis by targeting fibroblast-like synoviocytes". Nature Reviews Rheumatology. doi:10.1038/s41584-020-0413-5.

- Wechalekar MD, Smith MD (2014). "Utility of arthroscopic guided synovial biopsy in understanding synovial tissue pathology in health and disease states". World J. Orthop. 5 (5): 566–73. doi:10.5312/wjo.v5.i5.566. PMC 4133463. PMID 25405084.

- Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.