Action of 18 November 1809

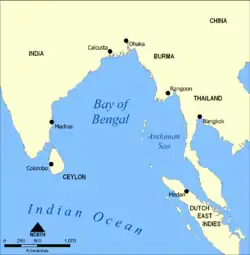

The Action of 18 November 1809 was the major engagement of a six-month cruise by a French frigate squadron in the Indian Ocean, during the Napoleonic Wars. The French commander, Commodore Jacques Hamelin, was engaged in commerce raiding across the Bay of Bengal. His squadron achieved local superiority, capturing numerous merchant ships and minor warships. On 18 November 1809, off the Nicobar Islands, three warships (two frigates and a corvette) under Hamelin's command encountered a convoy of three East Indiamen merchant vessels bound for British India, mainly carrying recruits for the army of the East India Company (EIC).

| Action of 18 November 1809 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mauritius campaign of the Napoleonic Wars | |||||||

Location of the Action of 18 November 1809 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Two frigates One brig | Three East Indiamen | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None |

4 killed 2 wounded Three East Indiamen captured (one subsequently recovered) | ||||||

The largest British merchant ship, Windham commanded by John Stewart, took advantage of a disrupted French formation to attack the frigate Manche. The two ships fought for an hour before Manche disengaged and Windham fled. The other two Indiamen declined to join the action and offered only token resistance to the more powerful French warships before surrendering. Windham evaded the French pursuit for five days before also being captured by the French flagship, Vénus.

Hamelin's force began transporting their captured prizes back to the distant French base on Île de France. A month after the battle, the squadron encountered a winter hurricane that heavily damaged several ships. Vénus only survived with the co-operation of the British prisoners she was carrying, including Stewart, who helped bring the ship safely to port. With the ships scattered after the storm, Windham was recaptured by a patrolling British frigate within a few miles of the French island. The other French ships and two East Indiamen successfully reached Île de France. Stewart and his crew were subsequently released in recognition of their assistance during the hurricane.

The action was one of three losses of East Indiamen convoys during 1809, which prompted the British to substantially increase their naval presence in the Indian Ocean during 1810.

Background

Following the decisive Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, the British Royal Navy held naval superiority in the seas around Europe. The few remaining French ships of the line were blockaded in their ports. Faster French frigates could sometimes evade the blockades; their combination of speed and firepower made them ideal for commerce raiding. The British economy relied upon sea trade with its distant empire, which was impossible for the Royal Navy to defend everywhere. Particularly profitable was the EIC's shipping to and from British India. To protect this trade, the EIC carried it in East Indiamen, a type of large armed merchant vessel. East Indiamen had enough resilience, firepower and crew to fight off pirates or small naval vessels, but were not warships and could not match a frigate in combat.[1]

In late 1808, the French Navy despatched a naval squadron of four large frigates from France to attack British trade routes in the East Indies, particularly with India. The goal was to damage the British economy and force the Royal Navy to send more ships to the Indian Ocean, thereby weakening their forces elsewhere. Command of the squadron was given to Commodore Jacques Hamelin, a skilled officer with substantial experience in frigate actions and commerce raiding.[1] The ships were to be maintained and supplied from two French islands in the western Indian Ocean: Île de France (modern Mauritius) and Île Bonaparte (Réunion).[2] These bases were thousands of miles from India and surrounded by open ocean, so Hamelin would need to sail substantial distances to find his targets.

After arriving in the Indian Ocean, Hamelin dispersed his frigates in the Bay of Bengal, ordering them to hunt merchant vessels. In spring 1809, the most successful of the French frigates was Caroline, which intercepted a convoy of East Indiamen in the Action of 31 May 1809. After a brief resistance by the larger vessels, one of the East Indiamen escaped, but two others were captured and brought to Île Bonaparte.[3] The Royal Navy forces in the region were under the command of Admiral Albemarle Bertie, based at the Cape of Good Hope Station (located at Simon's Town, now in South Africa). Bertie gathered a squadron of frigates, led by Commodore Josias Rowley in HMS Raisonnable, in roughly equivalent numbers to Hamelin's force.[3] Bertie ordered Rowley to blockade the two French islands and reconnoitre them for weaknesses that could be exploited in a future invasion. Rowley's first significant operation was the Raid on Saint Paul (a port on Île Bonaparte) on 21 September 1809, which captured Caroline, recovered her two East Indiamen prizes, and burned their cargoes in the French warehouses.[1]

Hamelin's cruise and Stewart's convoy

In July 1809, Hamelin departed Île de France in the frigate Vénus, accompanied the frigate Manche (under Captain Jean Dornal de Guy) and the corvette Créole. The frigates both carried at least 40 cannon and the corvette carried 14. All three ships were crewed by a full complement of experienced sailors, reinforced from the pool of unemployed men stranded on Île de France by the British blockade.[4] The frigate Bellone departed a month later and operated separately.

Hamelin led his small squadron towards the Bay of Bengal. On the way there, Vénus captured the EIC armed ship Orient on 26 July. Hamelin then turned east in search of more British shipping to attack, capturing several small merchant vessels off the Nicobar Islands.[5] He then turned south, towards the small trading port of Tappanooly (modern Sibolga) on Sumatra. On 10 October, the squadron raided Tappanooly, capturing its small British population and razing the town.[1] Hamelin then turned north, back towards the Bay of Bengal.

Months earlier, a convoy of three East Indiamen – Windham under captain John Stewart, Charlton under captain Charles Mortlock and United Kingdom under captain William D'Esterre – had departed Britain on a voyage to Calcutta, with Stewart in overall command.[6] They were to pick up a valuable cargo of trade goods in India before returning to Britain. On this outwards journey, their main cargo was over 200 passengers, primarily soldiers for the army of the EIC.

Stewart's three vessels had cargo capacities of approximately 800 tons burthen. They carried between 20 and 30 small cannon each, but were not warships: their crews were not trained to military standards and their guns were not as powerful as those carried on naval vessels. A large proportion of the crews were lascars, who were considered unreliable in combat.[7] On 11 November, these ships encountered HMS Rattlesnake, a British sloop, which warned them that French naval vessels were operating in the area. Stewart began rehearsing Windham's gunnery in case he should meet them.[8]

Engagement

At 06:00 on 18 November 1809, with the sailing season almost at an end, Hamelin sighted Stewart's convoy travelling northwards and gave chase. Ship for ship, the East Indiamen were outclassed by the French frigates, which were faster, stronger, more powerful, better armed and better trained for military action. In convoy, however, the British were still a tough target which could damage the French ships, which were thousands of miles from any friendly port. Four years earlier, at the Battle of Pulo Aura, a convoy of 29 East Indiamen had driven off a powerful French squadron by pretending to be ships of the line. However that ruse had been widely reported on both sides, so was unlikely to work again.[9]

The French squadron became disorganised in its initial pursuit of the British, with Manche falling substantially to leeward of Vénus and Créole.[6] Seeing this, Stewart decided to concentrate the fire of his three vessels in an attack on Manche, hoping to cause enough damage to drive the frigate away. Vénus might then be reluctant to attack alone. Signalling his intentions to the captains of Charlton and United Kingdom, Stewart turned towards Vénus and bore down on her. Hamelin, realising the threat to his scattered squadron, signalled for his ships to join up. Given the wind direction, it was obvious that Windham would reach Manche before the French ships could unite.[6]

By 08:00, it was clear that Stewart's plan was going to fail: Charlton and United Kingdom had not joined his attack, falling far behind Windham as their captains deliberately checked the advance towards the French.[10] Although Stewart now faced a superior foe alone, he had no option but to continue the attack: his ship was now too close to attempt to flee from the French frigate.[6] Manche's commander, Captain Dornal de Guy, opened fire at 09:30, repeatedly hitting Windham as she approached. Stewart, aware of his gunners' poor accuracy, held fire until his ship was as close as he could get to the more nimble French ship. When Windham finally opened fire the results were disappointing: the entire broadside fell far short of the French ship.[10] The more manoeuvrable Manche now approached Windham at close range, with the two ships firing at one another for over an hour. The other two East Indiamen did not move to support Windham, instead firing occasional shots at extreme range, to no effect.[6]

Hamelin ordered Manche to leave the battered Windham and rejoin the rest of the French squadron. Dornal de Guy pulled his ship away at 12:00; Stewart used the break in the action to effect rudimentary repairs. Hamelin sent Manche and Créole after the slow Charlton and United Kingdom, while his own ship Vénus closed with Windham. Stewart now decided that the battle was hopeless; with the agreement of his officers, he determined to abandon the other ships and attempt to escape alone.[11] Manche and Créole rapidly overhauled and captured Charlton and United Kingdom, whose captains made no attempt to escape and surrendered after only a token resistance. However, Vénus struggled to catch Windham, as Stewart threw all non-essential stores overboard in an effort to make his ship lighter and faster. The two ships became separated from the other vessels and continued the chase for five days. At 10:30 on 22 November Hamelin finally caught the British ship, which surrendered.[12]

Return to Île de France

Bellone, under Captain Guy-Victor Duperré, had been sailing independently of Hamelin's squadron and had also had a successful cruise, capturing the small British warship HMS Victor on 2 November and the 48-gun Portuguese frigate Minerve on 22 November in the northern Bay of Bengal, before sailing back to Île de France.[2] To the south, Hamelin and Dornal de Guy reunited with their prizes on 6 December and also determined to return to Île de France as the cyclone season, in which any ship in the Indian Ocean would be at serious risk of destruction by a sudden tropical cyclone, was fast approaching. This was a dangerous time to be at sea: the year before seven large East Indiamen had sunk with a thousand lives in two major hurricanes and the year before that, the flagship of Sir Thomas Troubridge, HMS Blenheim, had disappeared without a trace in similar circumstances,[13]

On 19 December, the first winter storm struck the French squadron. In the heavy waves and high winds, first Windham and then Vénus were separated from the convoy, Manche marshalling the remaining ships and continuing the southwards journey. Windham's French prize crew were able to regain control of their ship and continued on to Île de France alone, but Vénus was struck by an even larger hurricane on 27 December and lost all three topmasts in the gale.[12] The French crew panicked as the storm began, and refused to attend to the sails or even close the hatches: as a result the vessel almost foundered as huge amounts of water poured into the ship. In desperation, Hamelin called Captain Stewart to his cabin and requested that his men save the ship but demanded that Stewart give his word that his men would not attempt to escape or seize the frigate.[14] Stewart refused to give any such guarantee but agreed to help repair the damage and bring the ship to safety. After securing the weapons lockers aboard, Hamelin agreed and Stewart and his men cut away the wrecked masts and pumped the water out of the hold, repairing the ship so that she was able to continue her journey without fear of foundering.[12]

On 31 December, the battered Vénus docked in Rivière Noire and Stewart and his men, who had never had an opportunity to seize their freedom, were marched to Port Louis, where they witnessed the arrival of Manche, accompanied by Créole, Charlton and United Kingdom on 1 January 1810.[15] For their services, Stewart and his fellow prisoners were later released and allowed to sail to the Cape of Good Hope. There they discovered Windham, which had failed to arrive at Île de France. Although her prize crew had retained control of the ship following the storm, they had been sighted, chased, and seized within sight of Île de France on 29 December by the newly arrived British frigate HMS Magicienne under Captain Lucius Curtis. Bellone and her prizes arrived at Port Louis on 2 January, having slipped past Rowley's blockade during a period of calm weather.[15]

Aftermath

Casualties in the battle were minimal, the British losing four killed and two wounded while the French recorded no casualties at all.[6] The significance of the action lies in the ease with which French frigates operating from Île de France were able to attack and capture vital trade convoys without facing serious opposition. The action of 18 November was the second occasion in 1809 in which a British East India convoy was destroyed and another would be lost in the Action of 3 July 1810 the following year. These losses were exceptionally heavy, especially when combined with the 12 East Indiamen wrecked during 1809, and would eventually provoke a massive buildup of British forces in late 1810.[16] Despite the French success Vénus was never again able to operate independently in this manner. Hamelin was needed during 1810 to operate against the strong British frigate squadrons that returned in the spring to harass his cruisers and prepare for the planned invasions of Île Bonaparte and Île de France using the soldiers stationed on Rodrigues. The French commodore was ultimately unable to prevent these operations and was eventually captured in the Action of 18 September 1810, a personal engagement with Rowley on HMS Boadicea.[17]

Notes

- Gardiner, p. 93

- Gardiner, p. 92

- Woodman, p. 283

- James, p. 262

- James, p. 200

- James, p. 201

- Brenton, p. 398

- Taylor, p. 251

- Adkins, p. 185

- Taylor, p. 252

- Taylor, p. 253

- James, p. 202

- Troubridge, Thomas, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, P. K. Crimmin, (subscription required), Retrieved 30 October 2008

- Taylor, p. 254

- Woodman, p. 284

- Taylor, p. 267

- Gardiner, p. 96

References

- Adkins, Roy & Lesley (2006). The War for All the Oceans. Abacus. ISBN 0-349-11916-3.

- Brenton, Edward Pelham (1825). The Naval History of Great Britain, Vol. IV. C. Rice.

edward pelham brenton.

- Gardiner, Robert (2001) [1998]. The Victory of Seapower. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-359-1.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 5, 1808–1811. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-909-3.

- Taylor, Stephen (2008). Storm & Conquest: The Battle for the Indian Ocean, 1809. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22467-8.

- Woodman, Richard (2001). The Sea Warriors. Constable Publishers. ISBN 1-84119-183-3.