First French Empire

The First French Empire,[4] officially the French Republic (until 1809) then the French Empire (French: Empire Français; Latin: Imperium Francicum),[lower-alpha 2] was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental Europe at the beginning of the 19th century. Although France had already established a colonial empire overseas since the early 17th century, the French state had remained a kingdom under the Bourbons and a republic after the French Revolution. Historians refer to Napoleon's regime as the First Empire to distinguish it from the restorationist Second Empire (1852–1870) ruled by his nephew Napoleon III.

French Empire Empire Français Imperium Francicum | |

|---|---|

| 1804–1814, 1815 | |

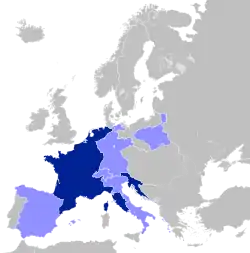

.svg.png.webp) The First French Empire at its greatest extent in 1812:

Satellite states and occupied territories of the Spanish in 1812 | |

| Capital | Paris |

| Common languages | French (official) Latin (formal) |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (State religion) Lutheranism Calvinism Judaism (Minority religion) |

| Government | Unitary Bonapartist absolute monarchy |

| Emperor | |

• 1804–1814/1815 | Napoleon I |

• 1815 | Napoleon II[lower-alpha 1] |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Sénat conservateur (until 1814) Chamber of Peers (from 22 April 1815 onward) | |

| Corps législatif (until 4 June 1814) Chamber of Representatives (from 22 April 1815 onward) | |

| Historical era | French Revolutionary Wars Napoleonic Wars |

| 18 May 1804 | |

• Coronation of Napoleon I | 2 December 1804 |

| 7 July 1807 | |

| 24 June 1812 | |

| 11 April 1814 | |

| 20 March – 7 July 1815/1815-1815 | |

| Area | |

| 1813[3] | 2,100,000 km2 (810,000 sq mi) |

| Currency | French franc |

| ISO 3166 code | FR |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of France |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

On 18 May 1804, Napoleon was granted the title Emperor of the French (Empereur des Français, pronounced [ɑ̃.pʁœʁ de fʁɑ̃.sɛ]) by the French Sénat (Senate) and was crowned on 2 December 1804,[8] signifying the end of the French Consulate and of the French First Republic. Despite his coronation, the empire continued to be called the “French Republic” until 1809. The French Empire achieved military supremacy in mainland Europe through notable victories in the War of the Third Coalition against Austria, Prussia, Russia, and allied nations, notably at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805.[9] French dominance was reaffirmed during the War of the Fourth Coalition, at the Battle of Jena–Auerstedt in 1806 and the Battle of Friedland in 1807,[10] before Napoleon's final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

A series of wars, known collectively as the Napoleonic Wars, extended French influence to much of Western Europe and into Poland. At its height in 1812, the French Empire had 130 departments, ruled over 44 million subjects, maintained an extensive military presence in Germany, Italy, Spain, and the Duchy of Warsaw, and counted Austria and Prussia as nominal allies.[11] Early French victories exported many ideological features of the Revolution throughout Europe: the introduction of the Napoleonic Code throughout the continent increased legal equality, established jury systems and legalized divorce, and seigneurial dues and seigneurial justice were abolished, as were aristocratic privileges in all places except Poland.[12] France's defeat in 1814 (and then again in 1815), marked the end of the Empire.

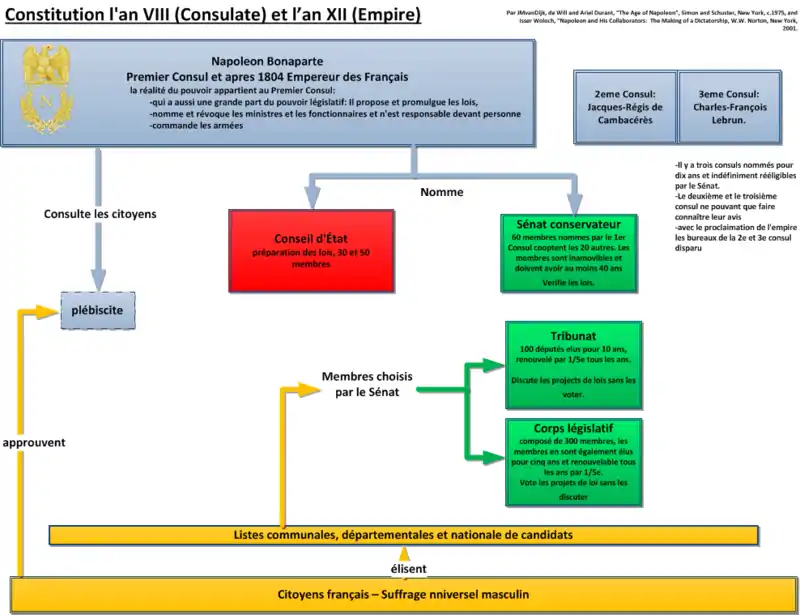

Origin

In 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte was confronted by Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès—one of five Directors constituting the executive branch of the French government—who sought his support for a coup d'état to overthrow the Constitution of the Year III. The plot included Bonaparte's brother Lucien, then serving as speaker of the Council of Five Hundred, Roger Ducos, another Director, and Talleyrand. On 9 November 1799 (18 Brumaire VIII under the French Republican Calendar) and the following day, troops led by Bonaparte seized control. They dispersed the legislative councils, leaving a rump legislature to name Bonaparte, Sieyès and Ducos as provisional Consuls to administer the government. Although Sieyès expected to dominate the new regime, the Consulate, he was outmaneuvered by Bonaparte, who drafted the Constitution of the Year VIII and secured his own election as First Consul. He thus became the most powerful person in France, a power that was increased by the Constitution of the Year X, which made him First Consul for life.

The Battle of Marengo (14 June 1800) inaugurated the political idea that was to continue its development until Napoleon's Moscow campaign. Napoleon planned only to keep the Duchy of Milan for France, setting aside Austria, and was thought to prepare a new campaign in the East. The Peace of Amiens, which cost him control of Egypt, was a temporary truce. He gradually extended his authority in Italy by annexing the Piedmont and by acquiring Genoa, Parma, Tuscany and Naples, and added this Italian territory to his Cisalpine Republic. Then he laid siege to the Roman state and initiated the Concordat of 1801 to control the material claims of the pope. When he recognised his error of raising the authority of the pope from that of a figurehead, Napoleon produced the Articles Organiques (1802) with the goal of becoming the legal protector of the papacy, like Charlemagne. To conceal his plans before their actual execution, he aroused French colonial aspirations against Britain and the memory of the 1763 Treaty of Paris, exacerbating British envy of France, whose borders now extended to the Rhine and beyond, to Hanover, Hamburg and Cuxhaven. Napoleon would have ruling elites from a fusion of the new bourgeoisie and the old aristocracy.[13]

On 12 May 1802, the French Tribunat voted unanimously, with the exception of Carnot, in favour of the Life Consulship for the leader of France.[14][15] This action was confirmed by the Corps Législatif. A general plebiscite followed thereafter resulting in 3,653,600 votes aye and 8,272 votes nay.[16] On 2 August 1802 (14 Thermidor, An X), Napoleon Bonaparte was proclaimed Consul for life.

Pro-revolutionary sentiment swept through Germany aided by the "Recess of 1803", which brought Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden to France's side. William Pitt the Younger, back in power over Britain, appealed once more for an Anglo-Austro-Russian coalition against Napoleon to stop the ideals of revolutionary France from spreading.

On 18 May 1804, Napoleon was given the title of "Emperor of the French" by the Senate; finally, on 2 December 1804, he was solemnly crowned, after receiving the Iron Crown of the Lombard kings, and was consecrated by Pope Pius VII in Notre-Dame de Paris.[lower-alpha 3]

In four campaigns, the Emperor transformed his "Carolingian" feudal republican and federal empire into one modelled on the Roman Empire. The memories of imperial Rome were for a third time, after Julius Caesar and Charlemagne, used to modify the historical evolution of France. Though the vague plan for an invasion of Great Britain was never executed, the Battle of Ulm and the Battle of Austerlitz overshadowed the defeat of Trafalgar, and the camp at Boulogne put at Napoleon's disposal the best military resources he had commanded, in the form of La Grande Armée.

Early victories

In the War of the Third Coalition, Napoleon swept away the remnants of the old Holy Roman Empire and created in southern Germany the vassal states of Bavaria, Baden, Württemberg, Hesse-Darmstadt and Saxony, which were reorganized into the Confederation of the Rhine. The Treaty of Pressburg, signed on 26 December 1805, extracted extensive territorial concessions from Austria, on top of a large financial indemnity. Napoleon's creation of the Kingdom of Italy, the occupation of Ancona, and his annexation of Venetia and its former Adriatic territories marked a new stage in the French Empire's progress.

.jpg.webp)

To create satellite states, Napoleon installed his relatives as rulers of many European states. The Bonapartes began to marry into old European monarchies, gaining sovereignty over many nations. Joseph Bonaparte replaced the dispossessed Bourbons in Naples; Louis Bonaparte was installed on the throne of the Kingdom of Holland, formed from the Batavian Republic; Joachim Murat became Grand-Duke of Berg; Jérôme Bonaparte was made son-in-law to the King of Württemberg and King of Westphalia; and Eugène de Beauharnais was appointed Viceroy of Italy while Stéphanie de Beauharnais married the son of the Grand Duke of Baden. In addition to the vassal titles, Napoleon's closest relatives were also granted the title of French Prince and formed the Imperial House of France.

Met with opposition, Napoleon would not tolerate any neutral power. On 6 August 1806 the Habsburgs abdicated their title of Holy Roman Emperor in order to prevent Napoleon from becoming the next Emperor, ending a political power which had endured for over a thousand years. Prussia had been offered the territory of Hanover to stay out of the Third Coalition. With the diplomatic situation changing, Napoleon offered Great Britain the province as part of a peace proposal. To this, combined with growing tensions in Germany over French hegemony, Prussia responded by forming an alliance with Russia and sending troops into Bavaria on 1 October 1806. During the War of the Fourth Coalition, Napoleon destroyed the Prussian armies at Jena and Auerstedt. Successive victories at Eylau and Friedland against the Russians finally ruined Frederick the Great's formerly mighty kingdom, obliging Russia and Prussia to make peace with France at Tilsit.

Height of the Empire

The Treaties of Tilsit ended the war between Russia and France and began an alliance between the two empires that held as much power as the rest of Europe. The two empires secretly agreed to aid each other in disputes. France pledged to aid Russia against the Ottoman Empire, while Russia agreed to join the Continental System against Britain. Napoleon also forced Alexander to enter the Anglo-Russian War and to instigate the Finnish War against Sweden in order to force Sweden to join the Continental System.

More specifically, Alexander agreed to evacuate Wallachia and Moldavia, which had been occupied by Russian forces as part of the Russo-Turkish War. The Ionian Islands and Cattaro, which had been captured by Russian admirals Ushakov and Senyavin, were to be handed over to the French. In recompense, Napoleon guaranteed the sovereignty of the Duchy of Oldenburg and several other small states ruled by the Russian emperor's German relatives.

The treaty removed about half of Prussia's territory: Cottbus was given to Saxony, the left bank of the Elbe was awarded to the newly created Kingdom of Westphalia, Białystok was given to Russia, and the rest of the Polish lands in Prussian possession were set up as the Duchy of Warsaw. Prussia was ordered to reduce its army to 40,000 men and to pay an indemnity of 100,000,000 francs. Observers in Prussia viewed the treaty as unfair and as a national humiliation.

Talleyrand had advised Napoleon to pursue milder terms; the treaties marked an important stage in his estrangement from the emperor. After Tilsit, instead of trying to reconcile Europe, as Talleyrand had advised, Napoleon wanted to defeat Britain and complete his Italian dominion. To the coalition of the northern powers, he added the league of the Baltic and Mediterranean ports, and to the bombardment of Copenhagen by the Royal Navy he responded with a second decree of blockade, dated from Milan on 17 December 1807.

The application of the Concordat and the taking of Naples led to Napoleon's first struggles with the Pope, centered around Pius VII renewing the theocratic affirmations of Pope Gregory VII. The emperor's Roman ambition was made more visible by the occupation of the Kingdom of Naples and of the Marches, and by the entry of Miollis into Rome; while General Junot invaded Portugal, Marshal Murat took control of formerly Roman Spain as Regent. Soon after, Napoleon had his brother, Joseph, crowned King of Spain and sent him there to take control.

Napoleon tried to succeed in the Iberian Peninsula as he had done in Italy, in the Netherlands, and in Hesse. However, the exile of the Spanish Royal Family to Bayonne, together with the enthroning of Joseph Bonaparte, turned the Spanish against Napoleon. After the Dos de Mayo riots and subsequent reprisals, the Spanish government began an effective guerrilla campaign, under the oversight of local Juntas. The Iberian Peninsula became a war zone from the Pyrenees to the Straits of Gibraltar and saw the Grande Armée facing the remnants of the Spanish Army, as well as British and Portuguese forces. General Dupont capitulated at Bailén to General Castaños, and Junot at Cintra, Portugal to General Wellesley.

Spain used up the soldiers needed for Napoleon's other fields of battle, and they had to be replaced by conscripts. Spanish resistance affected Austria, and indicated the potential of national resistance. The provocations of Talleyrand and Britain strengthened the idea that the Austrians could emulate the Spanish. On 10 April 1809, Austria invaded France's ally, Bavaria. The campaign of 1809, however, would not be nearly as long and troublesome for France as the one in Spain and Portugal. Following a short and decisive action in Bavaria, Napoleon opened up the road to the Austrian capital of Vienna for a second time. At Aspern, Napoleon suffered his first serious tactical defeat, along with the death of Jean Lannes, an able Marshal and dear friend of the emperor. The victory at Wagram, however, forced Austria to sue for peace. The Treaty of Schönbrunn, signed on 14 December 1809, resulted in the annexation of the Illyrian Provinces and recognized past French conquests.

The Pope was forcibly deported to Savona, and his domains were incorporated into the French Empire. The Senate's decision on 17 February 1810 created the title "King of Rome", and made Rome the capital of Italy. Between 1810 and 1812 Napoleon's divorce of Joséphine, and his marriage with Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria, followed by the birth of his son, shed light upon his future policy. He gradually withdrew power from his siblings and concentrated his affection and ambition on his son, the guarantee of the continuance of his dynasty, marking the high point of the Empire.

Intrigues and unrest

Undermining forces, however, had already begun to impinge on the faults inherent in Napoleon's achievements. Britain, protected by the English Channel and its navy, was persistently active, and rebellion of both the governing and of the governed broke out everywhere. Napoleon, though he underrated it, soon felt his failure in coping with the Peninsular War. Men like Baron von Stein, August von Hardenberg and Johann von Scharnhorst had begun secretly preparing Prussia's retaliation.

The alliance arranged at Tilsit was seriously shaken by the Austrian marriage, the threat of Polish restoration to Russia, and the Continental System. The very persons whom he had placed in power were counteracting his plans. With many of his siblings and relations performing unsuccessfully or even betraying him, Napoleon found himself obliged to revoke their power. Caroline Bonaparte conspired against her brother and against her husband Murat; the hypochondriac Louis, now Dutch in his sympathies, found the supervision of the blockade taken from him, and also the defense of the Scheldt, which he had refused to ensure. Jérôme Bonaparte lost control of the blockade on the North Sea shores. The very nature of things was against the new dynasties, as it had been against the old.

After national insurrections and family recriminations came treachery from Napoleon's ministers. Talleyrand betrayed his designs to Metternich and suffered dismissal. Joseph Fouché, corresponding with Austria in 1809 and 1810, entered into an understanding with Louis and also with Britain, while Bourrienne was convicted of speculation. By consequence of the spirit of conquest Napoleon had aroused, many of his marshals and officials, having tasted victory, dreamed of sovereign power: Bernadotte, who had helped him to the Consulate, played Napoleon false to win the crown of Sweden. Soult, like Murat, coveted the Spanish throne after that of Portugal, thus anticipating the treason of 1812.

The country itself, though flattered by conquests, was tired of self-sacrifice. The unpopularity of conscription gradually turned many of Napoleon's subjects against him. Amidst profound silence from the press and the assemblies, a protest was raised against imperial power by the literary world, against the excommunicated sovereign by Catholicism, and against the author of the continental blockade by the discontented bourgeoisie, ruined by the crisis of 1811. Even as he lost his military principles, Napoleon maintained his gift for brilliance. His Six Days' Campaign, which took place at the very end of the War of the Sixth Coalition, is often regarded as his greatest display of leadership and military prowess. But by then it was the end (or "the finish"), and it was during the years before when the nations of Europe conspired against France. While Napoleon and his holdings idled and worsened, the rest of Europe agreed to avenge the revolutionary events of 1792.

Fall

Napoleon had hardly succeeded in putting down the revolt in Germany when the emperor of Russia himself headed a European insurrection against Napoleon. To put an end to this, to ensure his own access to the Mediterranean and exclude his chief rival, Napoleon invaded Russia in 1812. Despite his victorious advance, the taking of Smolensk, the victory on the Moskva, and the entry into Moscow, he was defeated by the country and the climate, and by Alexander's refusal to make terms. After this came the terrible retreat in the harsh Russian winter, while all of Europe was turning against him. Pushed back, as he had been in Spain, from bastion to bastion, after the action on the Berezina, Napoleon had to fall back upon the frontiers of 1809, and then—having refused the peace offered to him by Austria at the Congress of Prague (4 June – 10 August 1813), from fear of losing Italy, where each of his victories had marked a stage in the accomplishment of his dream—on those of 1805, despite the victories at Lützen and Bautzen, and on those of 1802 after his disastrous defeat at Leipzig, when Bernadotte—now Crown Prince of Sweden—turned upon him, General Moreau also joined the Allies, and longstanding allied nations, such as Saxony and Bavaria, forsook him as well.

Following his retreat from Russia, Napoleon continued to retreat, this time from Germany. After the loss of Spain, reconquered by an Allied army led by Wellington, the uprising in the Netherlands preliminary to the invasion and the manifesto of Frankfurt (1 December 1813)[17] which proclaimed it, he was forced to fall back upon the frontiers of 1795; and was later driven further back upon those of 1792—despite the brilliant campaign of 1814 against the invaders. Paris capitulated on 30 March 1814, and the Delenda Carthago, pronounced against Britain, was spoken of Napoleon. The Empire briefly fell with Napoleon's abdication at Fontainebleau on 11 April 1814.

After less than a year's exile on the island of Elba, Napoleon escaped to France with a thousand men and four cannons. King Louis XVIII sent Marshal Ney to arrest him. Upon meeting Ney's army, Napoleon dismounted and walked into firing range, saying "If one of you wishes to kill his emperor, here I am!" But instead of firing, the soldiers went to join Napoleon's side shouting "Vive l'Empereur!" Napoleon retook the throne temporarily in 1815, reviving the Empire in what is known as the Hundred Days. However, he was defeated by the Seventh Coalition at the Battle of Waterloo. He surrendered himself to the British and was exiled to Saint Helena, a remote island in the South Atlantic, where he remained until his death in 1821. After the Hundred Days, the Bourbon monarchy was restored, with Louis XVIII regaining the throne of France, while the rest of Napoleon's conquests were disposed of in the Congress of Vienna.

Nature of Napoleon Bonaparte's rule

_2010-12-19_051.jpg.webp)

Napoleon gained support by appealing to some common concerns of the French people. These included dislike of the emigrant nobility who had escaped persecution, fear by some of a restoration of the Ancien Régime, a dislike and suspicion of foreign countries that had tried to reverse the Revolution—and a wish by Jacobins to extend France's revolutionary ideals.

Napoleon attracted power and imperial status and gathered support for his changes of French institutions, such as the Concordat of 1801 which confirmed the Catholic Church as the majority church of France and restored some of its civil status. Napoleon by this time, however, thought himself more of an enlightened despot. He preserved numerous social gains of the Revolution while suppressing political liberty. He admired efficiency and strength and hated feudalism, religious intolerance, and civil inequality.

Although a supporter of the radical Jacobins during the early days of the Revolution out of pragmatism, Napoleon became increasingly autocratic as his political career progressed, and once in power embraced certain aspects of both liberalism and authoritarianism—for example, public education, a generally liberal restructuring of the French legal system, and the emancipation of the Jews—while rejecting electoral democracy and freedom of the press.

Maps

French départements in 1801 during the Consulate

French départements in 1801 during the Consulate French départements in 1812

French départements in 1812 Map of the First French Empire in 1812, divided into 133 départements, with the kingdoms of Spain, Portugal, Italy and Naples, and the Confederation of the Rhine and Illyria and Dalmatia

Map of the First French Empire in 1812, divided into 133 départements, with the kingdoms of Spain, Portugal, Italy and Naples, and the Confederation of the Rhine and Illyria and Dalmatia Europe in 1812, with the French Empire at its peak before the Russian Campaign

Europe in 1812, with the French Empire at its peak before the Russian Campaign

See also

Notes

- According to his father's will only. Between 23 June and 7 July France was held by a Commission of Government of five members, which never summoned Napoleon II as emperor in any official act, and no regent was ever appointed while waiting the return of the king.[2]

- Domestically styled as French Republic until 1808: compare the French franc minted in 1808[5] and in 1809,[6] as well as Article 1 of the Constitution of the Year XII,[7] which reads in English The Government of the Republic is vested in an Emperor, who takes the title of Emperor of the French.

- Claims that Napoleon seized the crown out of the hands of Pope Pius VII during the ceremony—to avoid subjecting himself to the authority of the pontiff—are apocryphal; the coronation procedure had been agreed upon in advance. See also: Napoleon Tiara.

References

- https://frenchmoments.eu/national-motto-of-france/

- texte, France Auteur du (23 April 1815). "Bulletin des lois de la République française". Gallica.

- Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 475–504. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- texte, France Auteur du (23 January 1804). "Bulletin des lois de la République française". Gallica.

- http://www.lesfrancs.com/francais/1f1808rh.jpg

- http://www.lesfrancs.com/francais/1f1809rh.jpg

- "Constitution de l'An XII - Empire - 28 floréal An XII". Conseil constitutionnel.

- Thierry, Lentz. "The Proclamation of Empire by the Sénat Conservateur". napoleon.org. Fondation Napoléon. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- "Battle of Austerlitz". Britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- Hickman, Kennedy. "Napoleonic Wars: Battle of Friedland". militaryhistory.about.com. about.com. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution. p. 232

- Martyn Lyons pp. 234–36

- Haine, Scott (2000). The History of France (1st ed.). Greenwood Press. pp. 92. ISBN 978-0-313-30328-9.

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory (2006). The encyclopedia of the French revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars: a political, social, and military history, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 211. ISBN 978-1851096466.

Elected to the Tribunate in 1802, he [Carnot] showed himself increasingly alienated by Napoleon's personal ambition and voted against both the Consul for Life and the proclamation of the Empire. Unlike many former Revolutionaries, Carnot had little (...)

- Chandler, David G. (2000). Napoleon. Pen and Sword. p. 57. ISBN 978-1473816565.

- Bulletin des Lois

- The Frankfort Declaration, 1 December 1813: http://www.napoleon-series.org/research/government/diplomatic/c_frankfort.html

Further reading

Surveys

- Bruun, Geoffrey. Europe and the French Imperium, 1799–1814 (1938) online.

- Bryant, Arthur. Years of Endurance 1793–1802 (1942); and Years of Victory, 1802–1812 (1944) well-written surveys of the British story

- Colton, Joel and Palmer, R.R. A History of the Modern World. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1992. ISBN 0-07-040826-2

- Esdaile, Charles. Napoleon's Wars: An International History, 1803–1815 (2008); 645pp excerpt and text search a standard scholarly history

- Fisher, Todd & Fremont-Barnes, Gregory. The Napoleonic Wars: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 2004. ISBN 1-84176-831-6

- Godechot, Jacques; et al. (1971). The Napoleonic era in Europe. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 9780030841668.

- Grab, Alexander. Napoleon and the Transformation of Europe (Macmillan, 2003), country by country analysis

- Hazen, Charles Downer. The French Revolution and Napoleon (1917) online free

- Lefebvre, Georges (1969). Napoleon from 18 Brumaire to Tilsit, 1799–1807. Columbia University Press. influential wide-ranging history

- Lefebvre, Georges (1969). Napoleon; from Tilsit to Waterloo, 1807–1815. Columbia University Press.

- Lyons, Martyn. Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution. (St. Martin's Press, 1994)

- Muir, Rory. Britain and the Defeat of Napoleon: 1807–1815 (1996)

- Lieven, Dominic (2009). Russia Against Napoleon: The Battle for Europe, 1807 to 1814. Allen Lane/The Penguin Press. p. 617.Literary Review - Charles Esdaile on Russia Against Napoleon by Dominic Lieven

- Schroeder, Paul W. (1996). The Transformation of European Politics 1763–1848. Oxford U.P. pp. 177–560. ISBN 9780198206545. advanced diplomatic history of Napoleon and his era

- Pope, Stephen (1999). The Cassel Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars. Cassel. ISBN 978-0-304-35229-6.

- Rapport, Mike. The Napoleonic Wars: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford UP, 2013)

- Ross, Steven T. European Diplomatic History, 1789–1815: France Against Europe (1969)

- Rothenberg, Gunther E. (1988). "The Origins, Causes, and Extension of the Wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 18 (4): 771–793. doi:10.2307/204824. JSTOR 204824.

- Rowe, Michael (2014). "Borders, War, and Nation-Building in Napoleon's Europe". Borderlands in World History, 1700–1914. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 143–165. ISBN 978-1-137-32058-2.

- Schroeder, Paul W. The Transformation of European Politics 1763–1848 (1994) 920pp; online; advanced analysis of diplomacy

Napoleon

- Dwyer, Philip. Napoleon: The Path to Power (2008) excerpt vol 1; Citizen Emperor: Napoleon in Power (2013) excerpt and text search v 2; most recent scholarly biography

- Englund, Steven (2010). Napoleon: A Political Life. Scribner. ISBN 978-0674018037.

- McLynn, Frank. Napoleon: A Biography. New York: Arcade Publishing Inc., 1997. ISBN 1-55970-631-7

- Johnson, Paul (2002). Napoleon: A life. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-670-03078-1.; 200pp; quite hostile

- Markham, Felix (1963). Napoleon. Mentor.; 303pp; short biography by an Oxford scholar

- McLynn, Frank (1998). Napoleon. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6247-5. ASIN 0712662472.; well-written popular history

- Mowat, R.B. (1924) The Diplomacy of Napoleon (1924) 350pp online

- Roberts, Andrew. Napoleon: A Life (2014)

- Thompson, J.M. (1951). Napoleon Bonaparte: His Rise and Fall. Oxford U.P., 412pp; by an Oxford scholar

Military

- Bell, David A. The First Total War: Napoleon's Europe and the Birth of Warfare as We Know It (2008) excerpt and text search

- Broers, Michael, et al. eds. The Napoleonic Empire and the New European Political Culture (2012) excerpt and text search

- Chandler, David G. The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995. ISBN 0-02-523660-1

- Elting, John R. Swords Around a Throne: Napoleon's Grande Armée. New York: Da Capo Press Inc., 1988. ISBN 0-306-80757-2

- Gates, David. The Napoleonic Wars 1803–1815 (NY: Random House, 2011)

- Haythornthwaite, Philip J. Napoleon's Military Machine (1995) excerpt and text search

- Uffindell, Andrew. Great Generals of the Napoleonic Wars. Kent: Spellmount, 2003. ISBN 1-86227-177-1

- Rothenberg, E. Gunther. The Art of Warfare in the Age of Napoleon (1977)

- Smith, Digby George. The Greenhill Napoleonic Wars Data Book: Actions and Losses in Personnel, Colours, Standards and Artillery (1998)

Primary sources

- Anderson, F.M. (1904). The constitutions and other select documents illustrative of the history of France, 1789–1901. The H. W. Wilson company 1904., complete text online

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)