Adult development

Adult development encompasses the changes that occur in biological and psychological domains of human life from the end of adolescence until the end of one's life. These changes may be gradual or rapid and can reflect positive, negative, or no change from previous levels of functioning. Changes occur at the cellular level and are partially explained by biological theories of adult development and aging.[1] Biological changes influence psychological and interpersonal/social developmental changes, which are often described by stage theories of human development. Stage theories typically focus on "age-appropriate" developmental tasks to be achieved at each stage. Erik Erikson and Carl Jung proposed stage theories of human development that encompass the entire life span, and emphasized the potential for positive change very late in life.

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

|

|

The concept of adulthood has legal and socio-cultural definitions. The legal definition of an adult is a person who has reached the age at which they are considered responsible for their own actions and therefore legally accountable for them. This is referred to as the age of majority, which is age 18 in most cultures, although there is a variation from 16 to 21. The socio-cultural definition of being an adult is based on what a culture normatively views as being the required criteria for adulthood, which in turn, influences the lives of individuals within that culture. This may or may not coincide with the legal definition.[2] Current views on adult development in late life focus on the concept of successful aging, defined as "...low probability of disease and disease-related disability, high cognitive and physical functional capacity, and active engagement with life."[3]

Biomedical theories hold that one can age successfully by caring for physical health and minimizing loss in function, whereas psychosocial theories posit that capitalizing upon social and cognitive resources, such as a positive attitude or social support from neighbors and friends, is key to aging successfully.[4] Jeanne Louise Calment exemplifies successful aging as the longest living person, dying at the age of 122 years. Her long life can be attributed to her genetics (both parents lived into their 80s) and her active lifestyle and an optimistic attitude.[5][6] She enjoyed many hobbies and physical activities and believed that laughter contributed to her longevity. She poured olive oil on all of her food and skin, which she believed also contributed to her long life and youthful appearance.

Contemporary and classic theories

Changes in adulthood have been described by several theories and metatheories, which serve as a framework for adult development research.

Lifespan development theory

Life span development can be defined as age-relating experiences that occur from birth to the entirety of a human's life. The framework considers the lifelong accumulation of developmental gains and losses, with the relative proportion of gains to losses diminishing over an individual's lifetime. According to this theory, life span development has multiple trajectories (positive, negative, stable) and causes (biological, psychological, social, and cultural). Individual variation is a hallmark of this theory – not all individuals develop and age at the same rate and in the same manner.[7]

Bronfenbrenner's ecological theory

Bronfenbrenner's ecological theory is an environmental system theory and social ecological model which focuses on five environmental systems:

- Microsystem: This is the layer closest to a person and it represents the relationship and interactions a person has. Structures in the microsystem may include family, school, or work environments. At the microsystem level, bidirectional influences, which are interactions are between structures, are the strongest and have the most effect on a person.

- Mesosystem: This system provides connections to all structures within a person's microsystem.

- Exosystem: The large social system that is connected to a person's microsystem through its structures. There may not be direct interaction to elements within the social system, nevertheless, a person is affected by these interactions within their social system.

- Macrosystem: Considered to be the outermost layer of a person's environment, it encompasses the culture and society in which a person lives in and is affected by. It includes the values, beliefs, laws, and customs by which a culture/society is dictated by. The macrosystem ultimately influences the structures within systems and their interactions.

- Chronosystem: This system encompasses the changes that occur throughout time in a person's life. These changes can be external, such as when a person reaches puberty, or they can be internal, such as psychological developmental changes. [8]

Erik Erikson's theory of psychosocial development

Erik Erikson developed stages of ego development that extended through childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. He was trained in psychoanalysis and was highly influenced by Freud, but unlike Freud, Erikson believed that social interaction is very important to the individual's psychosocial development. His stage theory consists of 8 stages in life from birth to old age, each of which is characterized by a specific developmental task.[9] During each stage, one developmental task is dominant, but may be carried forward into later stages as well. According to Erikson, individuals may experience tension when advancing to new stages of development, and seek to establish equilibrium within each stage. This tension is often referred to as a "crisis," a psycho-social conflict, in which an individual experiences conflict between their inner and outer worlds that are relative to whichever stage they're in. [10] If equilibrium is not found for each task there are potential negative outcomes called maladaptation's (abnormally positive) and malignancies (abnormally negative), where malignancy is worse of the two.[10]

- Stage 1 – Trust vs. Mistrust (0 to 1.5 years)

Trust vs. Mistrust is experienced in the first years of life. Trust in infancy helps the child be secure about the world around them. Because an infant is completely dependent, they start building trust based on the dependability and quality if their caregivers. If a child successfully develops trust, he or she will feel safe and secure.

Maladaptation – sensory distortion (e.g. unrealistic, spoilt, deluded)

Malignancy – withdrawal (e.g. neurotic, depressive, afraid)

- Stage 2 – Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt (1.5 – 3 years)

After gaining trust in their caregivers, infants start to find out that they are responsible for their actions. They begin to make judgments and moving on their own. When toddlers are punished too severely or too often they are likely to feel ashamed and start doubting themselves.

Maladaptation – impulsivity (e.g. reckless, inconsiderate, thoughtless)

Malignancy – compulsion (e.g. anal, constrained, self-limiting)

- Stage 3 – Initiative vs. Guilt (3 – 6 years)

During preschool years children start to use their power and control over the world through playing and other social interactions. Children who successfully pass this stage feel capable and able to lead others, while those who do not are left with a sense of guilt, self-doubt, and lack of initiative.

Maladaptation – ruthlessness (e.g. exploitative, uncaring, dispassionate)

Malignancy – inhibition (e.g. risk-averse, unadventurous)

- Stage 4 – Industry vs. Inferiority (6 years to puberty)

When children interact with others they start to develop a sense of pride in their abilities and accomplishments. When parents, teachers, or peers command and encourage kids, they begin to feel confident in their skills. Successfully completing this stage leads to a strong belief in one's ability to handle tasks set in front of us.

Maladaptation – narrow virtuosity (e.g. workaholic, obsessive, specialist)

Malignancy – inertia (e.g. lazy, apathetic, purposeless)

- Stage 5 – Identity vs. Role Confusion (adolescence)

During adolescent years, children begin to find out who they are. They explore their independence and develop a sense of self. This is Erikson's fifth stage, Identity vs Confusion. Completing this stage leads to fidelity, an ability that Erikson described as useful to live by society's standards and expectations.[11]

Maladaptation – fanaticism (e.g. self-important, extremist)

Malignancy – repudiation (e.g. socially disconnected, cut-off)

- Stage 6 – Intimacy vs. Isolation (early adulthood)

In early adulthood, individuals begin to experience intimate relationships in which they must either commit to relating and connecting to others on a personal level or retreat into isolation, afraid of commitment or vulnerability. Having intimate relationships with others doesn’t necessarily entail a sexual element to the relationship, intimacy can be self-disclosure in a platonic relationship. By completing this stage, an individual has the skills to form close, lasting interpersonal relationships with others.[12]

Maladaptation – promiscuity (e.g. sexually needy, vulnerable)

Malignancy – exclusivity (e.g. loner, cold, self-contained)

- Stage 7 – Generativity vs. Stagnation (middle adulthood)

This stage usually begins when an individual has established a career and has a family. In this stage, an individual must either contribute significantly to their careers, families and communities in order to ensure success in the next generation or they stagnate, creating a threat to their well-being which can be referred to as a “mid-life crisis.” When individuals feel they have successfully fostered growth in themselves and their relationships, they will feel satisfied in their successes and contributions to the world.[13]

Maladaptation – overextension (e.g. do-gooder, busy-body, meddling)

Malignancy – rejectivity (e.g. disinterested, cynical)

- Stage 8 – Integrity vs. Despair (late adulthood)

This stage often occurs when an older individual is in retirement and expecting the end of their life. They reflect on their life and either come to the conclusion that they have found meaning and peace, or their lives were not fulfilling, and they didn't achieve what they wanted to. The former is self-accepting of who they've become, while the latter is not accepting of themselves or their circumstances in life, which leads to despair. [14]

Maladaptation – presumption (e.g. conceited, pompous, arrogant)

Malignancy – disdain (e.g. miserable, unfulfilled, blaming)

Michael Commons's theory

Michael Commons's Model of Hierarchical Complexity (MHC) is an enhancement and simplification of Inhelder and Piaget's developmental model. It offers a standard method of examining the universal pattern of development. For one task to be more hierarchically complex than another, the new task must meet three requirements: 1) It must be defined in terms of the lower stage actions; 2) it must coordinate the lower stage actions; 3) it must do so in a non-arbitrary way

- 0 Calculatory

- 1 Sensory and motor

- 2 Circular sensory-motor

- 3 Sensory-motor

- 4 Nominal

- 5 Sentential

- 6 Preoperational

- 7 Primary

- 8 Concrete

- 9 Abstract

- 10 Formal

- 11 Systematic

- 12 Metasystematic

- 13 Paradigmatic

- 14 Cross-paradigmatic

- 15 Meta-Cross-paradigmatic[15]

Carl Jung's theory

Carl Jung, a Swiss psychoanalyst, formulated four stages of development and believed that development was a function of reconciling opposing forces.[16]

- Childhood: (birth to puberty) Childhood has two substages. The archaic stage is characterized by sporadic consciousness, while the monarchic stage represents the beginning of logical and abstract thinking. The ego starts to develop."Jung believed that consciousness is formed in a child starting when a child can say the word “I”. And through that, the more a child distinguish him/herself from others and the world, the more ego develops. According to Jung, the psyche assumes a definite content not until puberty. That is when a teenager struggles through difficulties; he/she also begins to fantasize." [17]

- Youth: (after puberty until midlife/ 35 – 40) Maturing sexuality, growing consciousness, and a realization that the carefree days of childhood are gone forever. People strive to gain independence, find a mate, and raise a family.[18]

- Middle Life: (40-60) The realization that you will not live forever creates tension. If you desperately try to cling to youth, you will fail in the process of self-realization. Jung believed that in midlife, one confronts one's shadow. Religiosity may increase during this period, according to Jung.

- Old Age: (60 and over) Consciousness is reduced. Jung thought that death is the ultimate goal of life. By realizing this, people will not face death with fear, but with a hope for rebirth.

Daniel Levinson's theory

Daniel Levinson's theory is a set of psychosocial 'seasons' through which adults must pass as they move through early adulthood and midlife. Each of these seasons is created by the challenges of building or maintaining a life structure, by the social norms that apply to particular age groups, particularly concerning relationships and career.[19] The process that underlies all these stages is individuation - a movement towards balance and wholeness over time. The key stages that he discerned in early adulthood and midlife were as follows:

- Early Adult Transition (Ages 16–24)

- Forming a Life Structure (Ages 24–28)

- Settling down (Ages 29–34)

- Becoming One's Own Man (Ages 35–40)

- Midlife Transition (The early forties)

- Restabilization, into Late Adulthood (Age 45 and on)[20]

A biopsychosocial metatheory of adult development

The 'biopsychosocial' approach to adult development states that to understand human development in its fullness, biological, psychological, and social levels of analysis must be included. There are a variety of biopsychosocial meta-models, but all entail a commitment to the following four premises:

- Human development happens concurrently at biological, psychological, and social levels throughout life, and a full descriptive account of development must include all three levels.

- Development at each of these three levels reciprocally influences the other two levels; therefore nature (biology) and nurture (social environment) are in constant complex interaction when considering how and why psychological development occurs.

- Biological, psychological and social descriptions, and explanations are all as valid as each other, and no level has causal primacy over the other two.

- Any aspect of human development is best described and explained in relation to the whole person and their social context, as well as to their biological and cognitive-affective parts. This can be called a holistic or contextualist viewpoint, and can be contrasted with the reductionist approach to development, which tends to focus solely on biological or mechanistic explanations.[21]

Normative physical changes in adulthood

Physical development in midlife and beyond include changes at the biological level (senescence) and larger organ and musculoskeletal levels. Sensory changes and degeneration begin to be common in midlife. Degeneration can include the breakdown of muscle, bones, and joints. Which leads to physical ailments such as sarcopenia or arthritis.[22]

At the sensory level, changes occur to vision, hearing, taste, touch, and smell, and taste. Two common sensory changes that begin in midlife include our ability to see close objects and our ability to hear high pitches.[23][24] Other developmental changes to vision might include cataracts, glaucoma, and the loss of central visual field with macular degeneration.[25] Hearing also becomes impaired in midlife and aging adults, particularly in men. In the past 30 years, hearing impairment has doubled.[26] Hearing aids as an aid for hearing loss still leaves many individuals dissatisfied with their quality of hearing. Changes in olfaction and sense of taste can co-occur. "Olfactory dysfunction can impair quality of life and may be a marker for other deficits and illnesses" and can also lead to decreased satisfaction in taste when eating. Losses to the sense of touch are usually noticed when there is a decline in the ability to detect a vibratory stimulus. The loss of sense of touch can harm a person's fine motor skills such as writing and using utensils. The ability to feel painful stimuli is usually preserved in aging, but the process of decline for touch is accelerated in those with diabetes.[25]

Physical deterioration to the body begins to increase in midlife and late life, and includes degeneration of muscle, bones, and joints. Sarcopenia, a normal developmental change, is the degeneration of muscle mass, which includes both strength and quality.[27] This change occurs even in those who consider themselves athletes, and is accelerated by physical inactivity.[28] Many of the contributing factors that may cause sarcopenia to include neuronal and hormonal changes, inadequate nutrition, and physical inactivity.[27] Apoptosis has also been suggested as an underlying mechanism in the progression of sarcopenia. The prevalence of sarcopenia increases as people age and is associated with the increased likelihood of disability and restricted independence among elderly people. Approaches to preventing and treating sarcopenia are being explored by researchers. A specific preventive approach includes progressive resistance training, which is safe and effective for the elderly.[29]

Developmental changes to various organs and organ systems occur throughout life. These changes affect responses to stress and illness, and can compromise the body's ability to cope with the demand for organs.[30] The altered functioning of the heart, lungs, and even skin in old age can be attributed to factors like cell death or endocrine hormones. There are changes to the reproductive system in midlife adults, most notably menopause for women, the permanent end of fertility. In men, hormonal changes also affect their reproductive and sexual physiology, but these changes are not as extreme as those experienced by women.[31]

Illnesses associated with aging

As adult bodies undergo a variety of physical changes that cause health to decline, a higher risk of contracting a variety of illnesses, both physical and mental, is possible.[32]

Scientists have made a distinctive connection between aging and cancer. It has been shown that the majority of cancer cases occur in those over 50 years of age.[33] This may be due to the decline in the strength of the immune system as one ages or to co-existing conditions. There a variety of symptoms associated with cancer, commonly growths or tumors may be indicators of cancer. Radiation, chemotherapy, and in some cases, surgery, is used to treat cancer.

Osteoarthritis is one of the most commonly experienced illnesses in adults as they age. Although there are a variety of types of arthritis they all include very similar symptoms: aching joints, stiff joints, continued joint pain, and problems moving joints.

It has been found that older age does increase the risk factor of contracting cardiovascular disease. Hypertension and high cholesterol have also been found to increase the likelihood of acquiring cardiovascular disease, which is also commonly found in older adults. Cardiovascular diseases include a variety of heart conditions that may induce a heart attack or other heart-related problems. Healthy eating, exercise, and avoiding smoking are usually used to prevent cardiovascular disease.

Infection occurs more easily as one ages, as the immune system starts to slow and become less effective. Aging also changes how the immune system reacts to infection, making new infections harder to detect and attack. Essentially, the immune system has a higher chance of being compromised the older one gets.[34]

Adult neurogenesis and neuroplasticity

New neurons are constantly formed from stem cells in parts of the adult brain throughout adulthood, a process called adult neurogenesis. The hippocampus is the area of the brain that is most active in neurogenesis. Research shows that thousands of new neurons are produced in the hippocampus every day.[35] The brain constantly changes and rewires itself throughout adulthood, a process known as neuroplasticity. Evidence suggests that the brain changes in response to diet, exercise, social environment, stress, and toxin intake. These same external factors also influence genetic expression throughout adult life - a phenomenon known as genetic plasticity.[36]

Non-normative cognitive changes in adulthood

Dementia is characterized by persistent, multiple cognitive deficits in the domains including, but not limited to, memory, language, and visuospatial skills and can result from central nervous system dysfunction.[37][38][39] Two forms of dementia exist: degenerative and nondegenerative. The progression of nondegenerative dementias, like head trauma and brain infections, can be slowed or halted but degenerative forms of dementia, like Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, and Huntington's are irreversible and incurable.

Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) was discovered in 1907 by Dr. Alois Alzheimer, a German neuropathologist and psychiatrist. Physiological abnormalities associated with AD include neurofibrillary plaques and tangles. Neuritic plaques, that target the outer regions of the cortex, consist of withering neuronal material from a protein, amyloid-beta. Neurofibrillary tangles, paired helical filaments containing over-phosphorylated tau protein, are located within the nerve cell. Early symptoms of AD include difficulty remembering names and events, while later symptoms include impaired judgment, disorientation, confusion, behavior changes, and difficulty speaking, swallowing, and walking. After initial diagnosis, a person with AD can live, on average, an additional 3 to 10 years with the disease.[40] In 2013, it was estimated that 5.2 million Americans of all ages had AD.[41] Environmental factors such as head trauma, high cholesterol, and type 2 diabetes can increase the likelihood of AD.[42]

Huntington's disease

Huntington's disease (HD) named after George Huntington is a disorder that is caused by an inherited defect in a single gene on chromosome 4, resulting in a progressive loss of mental faculties and physical control.[43][44] HD affects personality, leads to involuntary muscle movements, cognitive impairment, and deterioration of the nervous system.[45][46] Symptoms usually appear between the ages of 30-50 but can occur at any age, including adolescence.[44] There is currently no cure for HD and treatments focus on managing symptoms and quality of life. Current estimates claim that 1 in 10,000 Americans have HD, however, 1 in 250,000 are at-risk of inheriting it from a parent.[47] Most individuals with HD live 10 to 20 years after a diagnosis.

Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD) was first described by James Parkinson in 1817. It typically affects people over the age of 50 and affects about 0.3% of developed populations.[48] PD is related to damaged nerve cells that produce dopamine.[49] Common symptoms experienced by people with PD include trembling of the hands, arms, legs, jaw, or head; rigidity (stiffness in limbs and the midsection); bradykinesia; and postural instability, leading to impaired balance and/or coordination.[50][51] Other areas such as speech, swallowing, olfaction, and sleep may be affected.[52] No cure for PD is available, but diagnosis and treatment can help relieve symptoms. Treatment options include medications like Carbidopa/Levodopa (L-dopa), that reduce the severity of motor symptoms in patients.[53] Alternative treatment options include non-pharmacological therapy. Surgery (pallidotomy, thalamotomy) is often viewed as the last viable option.[54]

Around 80% of patients that have Parkinson's diseases also suffer from tremors.[55] The tremor's severity is caused by dopamine levels and other factors.[56] Gait disturbances caused by Parkinson's disease may lead to falls.[57] Non-experts need to be aware of the features of Parkinson's disease and should have a basic understanding of how the condition should be treated between primary and secondary care.[58] Some cases of secondary Parkinsonism have been described as iatrogenic after the use of certain drugs such as phenothiazines and reserpine. The vast majority of Parkinsonism is still of unknown etiology and many hypotheses have been proposed.[59][60]

Mental health in adulthood and old age

Older adults represent a significant proportion of the population, and this proportion is expected to increase with time.[61] Mental health concerns of older adults are important at treatment and support levels, as well as policy issues. The prevalence of suicide among older adults is higher than in any other age group.[62][63]

Depression

.jpg.webp)

Depression is one of the most common disorders that presents in old age and is usually comorbid with other physical and psychiatric conditions, perhaps due to the stress induced by these conditions.[64] In older adults, depression presents as impairments already associated with age such as memory and psychomotor speed. Research indicates that higher levels of exercise can decrease the likelihood of depression in older adults even after taking into consideration factors such as chronic conditions, body mass index, and social relationships.[65] In addition to exercise, behavioral rehabilitation and prescribed antidepressants, which is well tolerated in older adults, can be used to treat depression.[64] Some research has indicated that a diet rich in folic acid and Vitamin B12 has been tied to preventing the development of depression among older adults.[66]

Anxiety

Anxiety is a relatively uncommon diagnosis in older adults and it is difficult to determine its prevalence.[67] Anxiety disorders in late life are more likely to be under-diagnosed because of medical comorbidity, cognitive decline, and changes in life circumstances that younger adults do not face. However, in the Epidemiological Catchment Area Project, researchers found that 6-month prevalence rates for anxiety disorders were lowest for the 65 years of age and older cohort. A recent study found that the prevalence of general anxiety disorder (GAD) in adults aged 55 or older in the United States was 33.7% with an onset before the age of 50.[68]

Loneliness in adulthood plays a major factor in depression and anxiety. According to Cacioppo, loneliness is described as a time in one's life when you are emotionally sad and feel as if there is a void in your life for social interactions.[69] Older adults tend to be lonelier due to death of a spouse or children moving away as a result of marriage or careers. Another factor is friends sometimes lose their mobility and can't socialize like they used to, as socialization plays an important role in protecting people from becoming lonely.[70] Loneliness is categorized in three parts, which are intimate loneliness, relational loneliness and collective loneliness.[71] All three types of loneliness has to do with your personal environment. Older adults sometimes depend on a child, spouse, or friend to be around for them socially for daily interactions and help with everyday chores. Loneliness can be treated by mostly social involvement, such as social skills and social support.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

ADHD is generally believed to be a children's disorder and is not commonly studied in adults. However, ADHD in adults results in lower household incomes, less educational achievement as well as a higher risk of marital issues and substance abuse.[72] Activities such as driving can be affected; adults who suffer from inattentiveness due to ADHD experience increased rates of car accidents.[73] ADHD impairs the driver's ability to drive in such a way that it resembles intoxicated driving. Adults with ADHD tend to be more creative, vibrant, aware of multiple activities, and are able to multitask when interested in a certain topic.[72]

Other mental disorders

The impact of mental disorders such as schizophrenia, delusional disorders, paraphrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder in adulthood is largely mediated by the environmental context. Those in hospitals and nursing homes differ in risk for a multitude of disorders in comparison to community-dwelling older adults.[74] Differences in how these environments treat mental illness and provide social support could help explain disparities and lead to a better knowledge of how these disorders are manifested in adulthood.

Optimizing health and mental well-being in adulthood

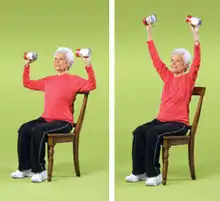

Exercising four to six times a week for thirty to sixty minutes has physical and cognitive effects such as lowering blood sugar and increasing neural plasticity. Physical activity reduces the loss of function by 10% each decade after the age of 60 and active individuals drop their rate of decline in half.[75] Cardio activities like walking promote endurance while strength, flexibility, and balance can all be improved through Tai Chi, yoga, and water aerobics. Diets containing foods with calcium, fiber, and potassium are especially important for good health while eliminating foods with high sodium or fat content. A well-balanced diet can increase resistance to disease and improve management of chronic health problems thus making nutrition an important factor for health and well-being in adulthood.[76]

Mental stimulation and optimism are vital to health and well-being in late adulthood. Adults who participate in intellectually stimulating activities every day are more likely to maintain their cognitive faculties and are less likely to show a decline in memory abilities.[77] Mental exercise activities such as crossword puzzles, spatial reasoning tasks, and other mentally stimulating activities can help adults increase their brain fitness.[78] Additionally, researchers have found that optimism, community engagement, physical activity and emotional support can help older adults maintain their resiliency as they continue through their life span.[79]

Managing stress and developing coping strategies

.JPG.webp)

Cognitive, physical, and social losses, as well as gains, are to be expected throughout the lifespan. Older adults typically self-report having a higher sense of well-being than their younger counterparts because of their emotional self-regulation. Researchers use Selective Optimization with Compensation Theory to explain how adults compensate for changes to their mental and physical abilities, as well as their social realities. Older adults can use both internal and external resources to help cope with these changes.[80]

The loss of loved ones and ensuing grief and bereavement are inevitable parts of life. Positive coping strategies are used when faced with emotional crises, as well as when coping with everyday mental and physical losses.[81] Adult development comes with both gains and losses, and it is important to be aware and plan ahead for these changes in order to age successfully.[82]

Personality in adulthood

Personality change and stability occur in adulthood. For example, self-confidence, warmth, self-control, and emotional stability increase with age, whereas neuroticism and openness to experience tend to decline with age.[83]

Personality change in adulthood

Two types of statistics are used to classify personality change over the life span. Rank-order change refers to a change in an individual's personality trait relative to other individuals. Mean-level change refers to absolute change in the individual's level of a certain trait over time.[84]

Controversy

The plaster hypothesis refers to personality traits tending to stabilize by age 30.[85] Stability in personality throughout adulthood has been observed in longitudinal and sequential research.[86][87] However, personality also changes. Research on the Big 5 Personality traits include a decrease in openness and extraversion in adulthood; an increase of agreeableness with age; peak conscientiousness in middle age; and a decrease of neuroticism late in life.[88] The concepts of both adjustment and growth as developmental processes help reconcile the large body of evidence for personality stability and the growing body of evidence for personality change.[89]

Intelligence in adulthood

According to the lifespan approach, intelligence is a multidimensional and multidirectional construct characterized by plasticity and interindividual variability.[90] Intellectual development throughout the lifespan is characterized by decline as well as stability and improvement.[90] Mechanics of intelligence, the basic architecture of information processing, decreases with age. Pragmatic intelligence, knowledge acquired through culture and experience, remains relatively stable with age.

The psychometric approach assesses intelligence based on scores on standardized tests such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale and Stanford Binet for children.[91] The Cognitive Structural approach measures intelligence by assessing the ways people conceptualize and solve problems, rather than by test scores.[91]

Developmental trends in intelligence

Primary mental abilities are independent groups of factors that contribute to intelligent behavior and include word fluency, verbal comprehension, spatial visualization, number facility, associative memory, reasoning, and perceptual speed.[92] Primary mental abilities decline around the age of 60 and may interfere with life functioning.[93] Secondary mental abilities include crystallized intelligence (knowledge acquired through experience) and fluid intelligence (abilities of flexible and abstract thinking). Fluid intelligence declines steadily in adulthood while crystallized intelligence increases and remains fairly stable with age until very late in life.[94]

Relationships

A combination of friendships and family is the support system for many individuals and an integral part of their lives from young adulthood to old age.

Family

Family relationships tend to be some of the most enduring bonds created within one's lifetime. As adults age, their children often feel a sense of filial obligation, in which they feel obligated to care for their parents. This is particularly prominent in Asian cultures. Marital satisfaction remains high in older couples, oftentimes increasing shortly after retirement. This can be attributed to increased maturity and reduced conflict within the relationship. However, when health problems arise, the relationship can become strained. Studies of spousal caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer's disease show marital satisfaction is significantly lower than in couples who are not afflicted.[95] Most people will experience the loss of a family member by death within their lifetime. This life event is usually accompanied by some form of bereavement, or grief. There is no set time frame for a mourning period after a loved one passes away, rather every person experiences bereavement in a different form and manner.[96]

Friends

Friendships, similar to family relationships, are often the support system for many individuals and a fundamental aspect of life from young adulthood to old age. Social friendships are important to emotional fulfillment, behavioral adjustment, and cognitive function.[97] Research has shown that emotional closeness in relationships greatly increases with age even though the number of social relationships and the development of new relationships begin to decline.[98] In young adulthood, friendships are grounded in similar aged peers with similar goals, though these relations might be more transitory.[99] In older adulthood, friendships have been found to be much deeper and longer lasting. While small in number, the quality of relationships is generally thought to be much stronger for older adults.[100]

Retirement

Retirement, or the point in which a person stops employment entirely, is often a time of psychological distress or a time of high quality and enhanced subjective well-being for individuals. Most individuals choose to retire between the ages of 50 to 70, and researchers have examined how this transition affects subjective well-being in old age.[101] One study examined subjective well-being in retirement as a function of marital quality, life course, and gender. Results indicated a positive correlation between well-being for married couples who retire around the same time compared to couples in which one spouse retires while the other continues to work.[101]

Retirement communities

Retirement communities provide for individuals who want to live independently but do not wish to maintain a home. They can maintain their autonomy while living in a community with individuals who are similar in age as well as within the same stage of life.[102]

Long-term care

Assisted living facilities are housing options for older adults that provide a supportive living arrangement for people who need assistance with personal care, such as bathing or taking medications, but are not so impaired that they need 24-hour care. These facilities provide older adults with a home-like environment and personal control while helping to meet residents' daily routines and special needs.[102]

Adult daycare is designed to provide social support, supervision, companionship, healthcare, and other services for adult family members who may pose safety risks if left at home alone while another family member, typically a caregiver, must work or otherwise leave the home. Adults who have cognitive impairments should be carefully introduced to adult daycare.[103]

Nursing home facilities provide residents with 24-hour skilled medical or intermediate care. A nursing home is typically seen as a decision of last resort for many family members. While the patient is receiving comprehensive care, the cost of nursing homes can be very high with a few insurance companies choosing to cover it. There is research that looks into other methods of care, such as independent care.[104]

Notes

- Hayflick, Leonard (November 1998). "How and why we age". Experimental Gerontology. 33 (7–8): 639–653. doi:10.1016/s0531-5565(98)00023-0. PMID 9951612. S2CID 34114351.

- Robinson, Oliver (2012). Development through Adulthood: An Integrative Sourcebook. Macmillan Education UK. ISBN 978-0-230-29799-9.

- Rowe, J. W.; Kahn, R. L. (1 August 1997). "Successful Aging". The Gerontologist. 37 (4): 433–440. doi:10.1093/geront/37.4.433. PMID 9279031.

- Bowling, Ann; Dieppe, Paul (24 December 2005). "What is successful ageing and who should define it?". BMJ. 331 (7531): 1548–1551. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1548. PMC 1322264. PMID 16373748.

- Danner, Deborah D.; Snowdon, David A.; Friesen, Wallace V. (2001). "Positive emotions in early life and longevity: Findings from the nun study". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 80 (5): 804–813. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.80.5.804. PMID 11374751.

- Diener, Ed; Chan, Micaela Y. (March 2011). "Happy People Live Longer: Subjective Well-Being Contributes to Health and Longevity". Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 3 (1): 1–43. doi:10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01045.x. S2CID 13490264.

- Baltes, Paul B.; Lindenberger, Ulman; Staudinger, Ursula M. (2007). "Life Span Theory in Developmental Psychology". Handbook of Child Psychology. American Cancer Society. doi:10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0111. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0025-7FD1-1. ISBN 978-0-470-14765-8.

- Addison, J. T. (1992). Urie Bronfenbrenner. Human Ecology, 20(2), 16-20

- Marcia, James; Josselson, Ruthellen (2013-02-21). "Eriksonian Personality Research and Its Implications for Psychotherapy". Journal of Personality. 81 (6): 617–629. doi:10.1111/jopy.12014. ISSN 0022-3506. PMID 23072442.

- Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the life cycle. London: W.W.Norton & Co.

- Santrock, J. W. (2014). Essentials of LifeSpan Development (3rd edition). New York: McGraw Hill

- Gold, Joshua M.; Rogers, Joan D. (2016-09-15). "Intimacy and Isolation: A Validation Study of Erikson's Theory". Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 35: 78–86. doi:10.1177/00221678950351008. S2CID 145305842.

- Malone, J. C.; Liu, S. R.; Vaillant, G. E.; Rentz, D. M.; Waldinger, R. J. (2016). "APA PsycNet". Developmental Psychology. 52 (3): 496–508. doi:10.1037/a0039875. PMC 5398200. PMID 26551530. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- Goodcase, Eric T.; Love, Heather A. (2016-08-17). "From Despair to Integrity: Using Narrative Therapy for Older Individuals in Erikson's Last Stage of Identity Development". Clinical Social Work Journal. 45 (4): 354–363. doi:10.1007/s10615-016-0601-6. ISSN 0091-1674. S2CID 151779539.

- Commons, Michael Lamport; Kjorlien, Olivia Alexandra (October 2016). "The Meta-Cross-Paradigmatic Order and Stage 16". Behavioral Development Bulletin. 21 (2): 154–164. doi:10.1037/bdb0000037.

- Crowther, Catherine (October 1997). "Carl Gustav Jung: A Biography By Frank McLynn. London: Bantam. 1996. 624 pp. £25.00. ISBN 0 593033 914". British Journal of Psychiatry. 171 (4): 396–397. doi:10.1192/s0007125000148469. ISSN 0007-1250.

- Child, Psych. "Changes in child Psychology".

- "The Stages of Life According to Carl Jung | Thomas Armstrong, Ph.D." www.institute4learning.com. Retrieved 2021-01-21.

- Levinson, Daniel J. (January 1986). "A conception of adult development". American Psychologist. 41 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.41.1.3.

- Wrightsman, Lawrence S. (1994). "Erikson's theory of psychosocial development". Adult personality development: Theories and concepts. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. pp. 59–84. doi:10.4135/9781452233796.n4. ISBN 978-1-4522-3379-6.

- Robinson, Oliver (2012). Development through Adulthood: An Integrative Sourcebook. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-29121-9.

- Lawrence, Reva C.; Helmick, Charles G.; Arnett, Frank C.; Deyo, Richard A.; Felson, David T.; Giannini, Edward H.; Heyse, Stephen P.; Hirsch, Rosemarie; Hochberg, Marc C.; Hunder, Gene G.; Liang, Matthew H.; Pillemer, Stanley R.; Steen, Virginia D.; Wolfe, Frederick (May 1998). "Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 41 (5): 778–99. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<778::AID-ART4>3.0.CO;2-V. PMID 9588729.

- Gates, George A; Mills, John H (September 2005). "Presbycusis". The Lancet. 366 (9491): 1111–1120. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67423-5. PMID 16182900. S2CID 208788711.

- Glasser, Adrian; Campbell, Melanie C.W. (January 1998). "Presbyopia and the optical changes in the human crystalline lens with age". Vision Research. 38 (2): 209–229. doi:10.1016/s0042-6989(97)00102-8. PMID 9536350. S2CID 7873653.

- Nusbaum, Neil J. (March 1999). "Aging and Sensory Senescence". Southern Medical Journal. 92 (3): 267–275. doi:10.1097/00007611-199903000-00002. PMID 10094265.

- Strawbridge, William J.; Wallhagen, Margaret I.; Shema, Sarah J.; Kaplan, George A. (1 June 2000). "Negative Consequences of Hearing Impairment in Old Age". The Gerontologist. 40 (3): 320–326. doi:10.1093/geront/40.3.320. PMID 10853526.

- Marzetti, Emanuele; Leeuwenburgh, Christiaan (December 2006). "Skeletal muscle apoptosis, sarcopenia and frailty at old age". Experimental Gerontology. 41 (12): 1234–1238. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2006.08.011. PMID 17052879. S2CID 23566430.

- Roubenoff, R. (June 2000). "Sarcopenia and its implications for the elderly". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 54 (3): S40–S47. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601024. PMID 11041074. S2CID 35889428.

- Baumgartner, R. N.; Koehler, K. M.; Gallagher, D.; Romero, L.; Heymsfield, S. B.; Ross, R. R.; Garry, P. J.; Lindeman, R. D. (15 April 1998). "Epidemiology of Sarcopenia among the Elderly in New Mexico". American Journal of Epidemiology. 147 (8): 755–763. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009520. PMID 9554417.

- Evers, B. Mark; Townsend, Courtney M.; Thompson, James C. (February 1994). "Organ Physiology of Aging". Surgical Clinics of North America. 74 (1): 23–39. doi:10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46226-2. PMID 8108769.

- Hermann, M; Untergasser, G; Rumpold, H; Berger, P (December 2000). "Aging of the male reproductive system". Experimental Gerontology. 35 (9–10): 1267–1279. doi:10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00159-5. PMID 11113607. S2CID 25814453.

- Bjorklund, B.R. The Journey of Adulthood. Prentice Hall.

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2017, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2017/, based on November 2019 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2020.

- Schaie, K. Warner; Gribbin, Kathy (January 1975). "Adult Development and Aging". Annual Review of Psychology. 26 (1): 65–96. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.26.020175.000433. PMID 1094935.

- Lledo, Pierre-Marie; Alonso, Mariana; Grubb, Matthew S. (March 2006). "Adult neurogenesis and functional plasticity in neuronal circuits". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 7 (3): 179–193. doi:10.1038/nrn1867. PMID 16495940. S2CID 6687815.

- Gottlieb, Gilbert (1998). "Normally occurring environmental and behavioral influences on gene activity: From central dogma to probabilistic epigenesis". Psychological Review. 105 (4): 792–802. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.105.4.792-802. PMID 9830380.

- Kempler, Daniel (2005). Neurocognitive Disorders in Aging. SAGE. ISBN 978-0-7619-2163-9.

- Bayles, Kathryn A; Tomoeda, Cheryl K (1995). The ABCs of dementia (2nd ed.). Canyonlands. ISBN 978-0-9639381-2-1.

- Borda, Cynthia (2006). Alzheimer's Disease and Memory Drugs. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0190-3.

- Zanetti, O.; Solerte, S.B.; Cantoni, F. (January 2009). "Life expectancy in Alzheimer's disease (AD)". Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 49: 237–243. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2009.09.035. PMID 19836639.

- Thies, William; Bleiler, Laura (March 2013). "2013 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures". Alzheimer's & Dementia. 9 (2): 208–245. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.003. PMID 23507120. S2CID 7584242.

- Kelly, Evelyn B. (2008). Alzheimer's Disease. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1811-6.

- "Huntington's Disease".

- "Fast Facts About HD" (PDF). Huntington's Disease Society of America. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2011.

- The Gale encyclopedia of alternative medicine. Fundukian, Laurie J., 1970- (3rd ed.). Detroit: Gale, Cengage Learning. 2009. ISBN 978-1-4144-4872-5. OCLC 222134974.CS1 maint: others (link)

- project editor, Deirdre S. Blanchfield (2016). The Gale encyclopedia of children's health : infancy through adolescence (Third ed.). Farmington Hills, MI. ISBN 978-1-4103-3274-5. OCLC 945448821.

- "Parkinson's Disease".

- Sveinbjornsdottir, Sigurlaug (2016). "The clinical symptoms of Parkinson's disease". Journal of Neurochemistry. 139 (S1): 318–324. doi:10.1111/jnc.13691. ISSN 1471-4159. PMID 27401947. S2CID 44378445.

- de Lau, Lonneke ML; Breteler, Monique MB (June 2006). "Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease". The Lancet Neurology. 5 (6): 525–535. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70471-9. PMID 16713924. S2CID 39310242.

- Kouli, Antonina; Torsney, Kelli M.; Kuan, Wei-Li (2018), Stoker, Thomas B.; Greenland, Julia C. (eds.), "Parkinson's Disease: Etiology, Neuropathology, and Pathogenesis", Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects, Brisbane (AU): Codon Publications, ISBN 978-0-9944381-6-4, PMID 30702842, retrieved 2020-12-15

- Chou, Kelvin L.; Taylor, Jennifer L.; Patil, Parag G. (November 2013). "The MDS−UPDRS tracks motor and non-motor improvement due to subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation in Parkinson disease". Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 19 (11): 966–969. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.06.010. PMC 3825788. PMID 23849499.

- Sveinbjornsdottir, Sigurlaug (2016). "The clinical symptoms of Parkinson's disease". Journal of Neurochemistry. 139 (S1): 318–324. doi:10.1111/jnc.13691. ISSN 1471-4159. PMID 27401947. S2CID 44378445.

- Hauser, Robert A; Hsu, Ann; Kell, Sherron; Espay, Alberto J; Sethi, Kapil; Stacy, Mark; Ondo, William; O'Connell, Martin; Gupta, Suneel (April 2013). "Extended-release carbidopa-levodopa (IPX066) compared with immediate-release carbidopa-levodopa in patients with Parkinson's disease and motor fluctuations: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind trial". The Lancet Neurology. 12 (4): 346–356. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70025-5. PMID 23485610. S2CID 21819903.

- Lang, Anthony E; Obeso, Jose A (May 2004). "Challenges in Parkinson's disease: restoration of the nigrostriatal dopamine system is not enough". The Lancet Neurology. 3 (5): 309–316. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00740-9. PMID 15099546. S2CID 6551470.

- "Parkinson's Tremors: What You Need to Know". WebMD. Retrieved 2021-01-19.

- Pasquini, Jacopo; Ceravolo, Roberto; Qamhawi, Zahi; Lee, Jee-Young; Deuschl, Günther; Brooks, David James; Bonuccelli, Ubaldo; Pavese, Nicola (2018-03-01). "Progression of tremor in early stages of Parkinson's disease: a clinical and neuroimaging study". Brain. 141 (3): 811–821. doi:10.1093/brain/awx376. ISSN 0006-8950. PMID 29365117. S2CID 43631583.

- Sveinbjornsdottir, Sigurlaug (2016). "The clinical symptoms of Parkinson's disease". Journal of Neurochemistry. 139 (S1): 318–324. doi:10.1111/jnc.13691. ISSN 1471-4159. PMID 27401947. S2CID 44378445.

- Magee, Kenneth R.; Elliott, Alta (July 1955). "Parkinson's Disease". The American Journal of Nursing. 55 (7): 814–817. doi:10.2307/3469061. JSTOR 3469061. PMID 14388044.

- Wirdefeldt, Karin; Adami, Hans-Olov; Cole, Philip; Trichopoulos, Dimitrios; Mandel, Jack (June 2011). "Epidemiology and etiology of Parkinson's disease: a review of the evidence". European Journal of Epidemiology. 26 (S1): S1-58. doi:10.1007/s10654-011-9581-6. ISSN 0393-2990. PMID 21626386. S2CID 38023183.

- Sasco, Annie J.; Paffenbarger, Ralph S. (November 1990). "Smoking and Parkinsonʼs Disease". Epidemiology. 1 (6): 460–465. doi:10.1097/00001648-199011000-00008. JSTOR 25759850. PMID 2090284. S2CID 21995635.

- Zarit, S. H., & Zarit, J. M. (1998). Mental disorders in older adults: Fundamentals of assessment and treatment. New York: Guilford Press.

- Garand, Linda; Mitchell, Ann M.; Dietrick, Ann; Hijjawi, Sophia P.; Pan, Di (May 2006). "Suicide in Older Adults: Nursing Assessment of Suicide Risk". Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 27 (4): 355–370. doi:10.1080/01612840600569633. ISSN 0161-2840. PMC 2864075. PMID 16546935.

- Mello-Santos, Carolina de; Bertolote, José Manuel; Wang, Yuan-Pang (June 2005). "Epidemiology of suicide in Brazil (1980 - 2000): characterization of age and gender rates of suicide". Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry. 27 (2): 131–134. doi:10.1590/S1516-44462005000200011. ISSN 1516-4446. PMID 15962138.

- Alexopoulos, George S (June 2005). "Depression in the elderly". The Lancet. 365 (9475): 1961–1970. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66665-2. PMID 15936426. S2CID 34666321.

- Strawbridge, W. J.; Deleger, S; Roberts, RE; Kaplan, GA (15 August 2002). "Physical Activity Reduces the Risk of Subsequent Depression for Older Adults". American Journal of Epidemiology. 156 (4): 328–334. doi:10.1093/aje/kwf047. PMID 12181102.

- Walker, Janine G.; Mackinnon, Andrew J.; Batterham, Philip; Jorm, Anthony F.; Hickie, Ian; McCarthy, Affrica; Fenech, Michael; Christensen, Helen (July 2010). "Mental health literacy, folic acid and vitamin B12, and physical activity for the prevention of depression in older adults: randomised controlled trial". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 197 (1): 45–54. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075291. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 20592433.

- Scogin, Forrest R. (1998). "Anxiety in old age". In Nordhus, Inger Hilde; VandenBos, Gary R.; Berg, Stig; Fromholt, Pia (eds.). Clinical Geropsychology. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. pp. 205–209. ISBN 978-1-55798-519-4.

- Wolitzky-Taylor, Kate B.; Castriotta, Natalie; Lenze, Eric J.; Stanley, Melinda A.; Craske, Michelle G. (February 2010). "Anxiety disorders in older adults: a comprehensive review". Depression and Anxiety. 27 (2): 190–211. doi:10.1002/da.20653. PMID 20099273. S2CID 12981577.

- Caccioppo, S (2015). "Loneliness: clinical import and interventions". Association for Psychological Science. 10 (Perspective on psychological science): 238–249. doi:10.1177/1745691615570616. PMC 4391342. PMID 25866548.

- Singh, Archana; Misra, Nishi (2009). "Loneliness, depression and sociability in old age". Industrial Psychiatry Journal. 18 (1): 51–55. doi:10.4103/0972-6748.57861. PMC 3016701. PMID 21234164.

- Kassin, Saul; Fein, Steven; Markus, Hazel Rose (2007). Social Psychology (10th ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 356–357. ISBN 978-1-305-58022-0.

- Brod, Meryl; Schmitt, Eva; Goodwin, Marc; Hodgkins, Paul; Niebler, Gwendolyn (June 2012). "ADHD burden of illness in older adults: a life course perspective". Quality of Life Research. 21 (5): 795–799. doi:10.1007/s11136-011-9981-9. PMID 21805205. S2CID 23837863.

- Reimer, Bryan; D’Ambrosio, Lisa A.; Gilbert, Jennifer; Coughlin, Joseph F.; Biederman, Joseph; Surman, Craig; Fried, Ronna; Aleardi, Megan (November 2005). "Behavior differences in drivers with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: The driving behavior questionnaire". Accident Analysis & Prevention. 37 (6): 996–1004. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2005.05.002. PMID 15955521.

- Zarit, Steven H.; Zarit, Judy M. (1998). Mental Disorders in Older Adults: Fundamentals of Assessment and Treatment. Guilford Publications. ISBN 978-1-57230-368-3.

- "Program Summary: Healthy Moves for Aging Well". NCOA.

- "How to prevent and manage chronic diseases with nutrition-conscious diet?". www.menusano.com. Retrieved 2020-10-07.

- Daffner, Kirk R.; Ryan, Katherine K.; Williams, Danielle M.; Budson, Andrew E.; Rentz, Dorene M.; Wolk, David A.; Holcomb, Phillip J. (October 2006). "Increased Responsiveness to Novelty is Associated with Successful Cognitive Aging". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 18 (10): 1759–1773. doi:10.1162/jocn.2006.18.10.1759. PMID 17014379. S2CID 2157698.

- Cavanaugh, John C.; Blanchard-Fields, Fredda (January 2018). "Attention and Memory". Adult Development and Aging. Cengage Learning. pp. 157–184. ISBN 978-1-337-67012-8.

- Dainese, Sara M.; Allemand, Mathias; Ribeiro, Nadja; Bayram, Sanem; Martin, Mike; Ehlert, Ulrike (January 2011). "Protective Factors in Midlife: How Do People Stay Healthy?". GeroPsych. 24 (1): 19–29. doi:10.1024/1662-9647/a000032.

- Urry, Heather L.; Gross, James J. (December 2010). "Emotion Regulation in Older Age". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 19 (6): 352–357. doi:10.1177/0963721410388395. S2CID 1400335.

- Hansson, Robert O.; Stroebe, Margaret S. (2007). Bereavement in Late Life: Coping, Adaptation, and Developmental Influences. American Psychological Association. ISBN 978-1-59147-472-2.

- Kahana, Eva; Kelley-Moore, Jessica; Kahana, Boaz (May 2012). "Proactive aging: A longitudinal study of stress, resources, agency, and well-being in late life". Aging & Mental Health. 16 (4): 438–451. doi:10.1080/13607863.2011.644519. PMC 3825511. PMID 22299813.

- Srivastava, Sanjay; John, Oliver P.; Gosling, Samuel D.; Potter, Jeff (May 2003). "Development of personality in early and middle adulthood: Set like plaster or persistent change?". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 84 (5): 1041–1053. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1041. PMID 12757147.

- Schwaba, Ted; Bleidorn, Wiebke (2018). "Individual differences in personality change across the adult life span". Journal of Personality. 86 (3): 450–464. doi:10.1111/jopy.12327. ISSN 0022-3506. PMID 28509384.

- Costa, Paul T.; McCrae, Robert R. (1994). "Set like plaster? Evidence for the stability of adult personality". In Heatherton, T. F.; Weinberger, J. L. (eds.). Can personality change?. pp. 21–40. doi:10.1037/10143-002. ISBN 1-55798-213-9.

- Leon, Gloria R.; Gillum, Brenda; Gillum, Richard; Gouze, Marshall (June 1979). "Personality stability and change over a 30-year period—middle age to old age". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 47 (3): 517–524. doi:10.1037//0022-006x.47.3.517. PMID 528720.

- Mõttus, René; Johnson, Wendy; Deary, Ian J. (March 2012). "Personality traits in old age: Measurement and rank-order stability and some mean-level change" (PDF). Psychology and Aging. 27 (1): 243–249. doi:10.1037/a0023690. PMID 21604884.

- Donnellan, M. Brent; Lucas, Richard E. (September 2008). "Age differences in the big five across the life span: Evidence from two national samples". Psychology and Aging. 23 (3): 558–566. doi:10.1037/a0012897. PMC 2562318. PMID 18808245.

- Mühlig-Versen, Andrea; Bowen, Catherine E.; Staudinger, Ursula M. (2012). "Personality plasticity in later adulthood: Contextual and personal resources are needed to increase openness to new experiences". Psychology and Aging. 27 (4): 855–866. doi:10.1037/a0029357. PMID 22846062.

- Baltes, Paul B. (1987). "Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline". Developmental Psychology. 23 (5): 611–626. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.23.5.611.

- Neisser, Ulric; Boodoo, Gwyneth; Bouchard, Thomas J.; Boykin, A. Wade; Brody, Nathan; Ceci, Stephen J.; Halpern, Diane F.; Loehlin, John C.; Perloff, Robert; Sternberg, Robert J.; Urbina, Susana (February 1996). "Intelligence: Knowns and unknowns". American Psychologist. 51 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.51.2.77.

- Thurstone, L. L. (1938). "Primary Mental Abilities". Psychometric Monographs. 1 (2813): Xi-121. PMID 18933605. NAID 10011544177.

- Hertzog, Christopher; Schaie, K. Warner (1988). "Stability and change in adult intelligence: II. Simultaneous analysis of longitudinal means and covariance structures". Psychology and Aging. 3 (2): 122–130. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.3.2.122. PMID 3268250.

- Horn, John L.; Cattell, Raymond B. (1967). "Age differences in fluid and crystallized intelligence". Acta Psychologica. 26 (2): 107–129. doi:10.1016/0001-6918(67)90011-X. PMID 6037305.

- Cavanaugh, John C.; Blanchard-Fields, Fredda (January 2018). "Where People Live: Person-Environment Interactions". Adult Development and Aging. Cengage Learning. pp. 126–156. ISBN 978-1-337-67012-8.

- Wrzus, Cornelia; Hänel, Martha; Wagner, Jenny; Neyer, Franz J. (2013). "Social network changes and life events across the life span: A meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 139 (1): 53–80. doi:10.1037/a0028601. PMID 22642230. S2CID 25046835.

- Seeman, Teresa E.; Lusignolo, Tina M.; Albert, Marilyn; Berkman, Lisa (2001). "Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging". Health Psychology. 20 (4): 243–255. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.20.4.243. PMID 11515736.

- Cacioppo, John T.; Hawkley, Louise C.; Thisted, Ronald A. (2010). "Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study". Psychology and Aging. 25 (2): 453–463. doi:10.1037/a0017216. PMC 2922929. PMID 20545429.

- Shulman, Norman (1975). "Life-Cycle Variations in Patterns of Close Relationships". Journal of Marriage and Family. 37 (4): 813–821. doi:10.2307/350834. JSTOR 350834.

- Larson, Reed; Mannell, Roger; Zuzanek, Jiri (1986). "Daily well-being of older adults with friends and family". Psychology and Aging. 1 (2): 117–126. doi:10.1037//0882-7974.1.2.117. PMID 3267387.

- Kim, Jungmeen E.; Moen, Phyllis (June 2001). "Is Retirement Good or Bad for Subjective Well-Being?". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 10 (3): 83–86. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00121. S2CID 12604129.

- "Choosing a long-term care setting: Facility types - review the choices". Oregon Department of Human Services. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016.

- Brandburg, G. L. (2007). Making the transition to nursing home life: A framework to help older adults adapt to the long-term care environment. Journal of gerontological nursing, 33(6), 50-56.

- Matson, Johnny L.; Dempsey, Timothy; Fodstad, Jill C. (November 2009). "The effect of Autism Spectrum Disorders on adaptive independent living skills in adults with severe intellectual disability". Research in Developmental Disabilities. 30 (6): 1203–1211. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2009.04.001. ISSN 0891-4222. PMID 19450950.

External links

- "Laboratory of Adult Development". Massachusetts General Hospital.

- "Journal of Adult Development". Springer.

- "Psychology and Aging". APA Publishing.

- "National Center for the Study of Adult Learning and Literacy (NCSALL)".