Affordable housing by country

Affordable housing is housing which is deemed affordable to those with a median household income[1] as rated by the national government or a local government by a recognized housing affordability index. The challenges of promoting affordable housing varies by location.

.jpg.webp)

Australia

Australians in receipt of many social security benefits from Centrelink who rent housing from a private landlord are eligible for rent assistance. Rent assistance is a subsidy paid directly to the tenant in addition to the basic Centrelink benefit such as the Age Pension or the Disability Pension. The amount of rent assistance paid depends on the amount of rent payable, whether the tenant has dependents and how many dependents there are. Tenants who live in public housing in Australia are not eligible for rent assistance.[2]

Australians buying a home for the first time are eligible for a first home owner grant. These grants were introduced on 1 July 2000 and are jointly funded by the Commonwealth government and the state and territory governments. First home buyers are currently eligible for a grant of A$7000 to alleviate the costs of entering the housing market.[3]

The Commonwealth government in 2008 introduced first home saver accounts, whereby those saving for a new home are eligible for government contributions to their savings account, subject to conditions.[4]

Department of Housing Affordable Homes Scheme

The long-term goal of the Department is to deliver at least 20,000 more affordable homes by 2020 for low to moderate income earners, through the Opening Doors Scheme.[5] Opening Doors offers two ways for Western Australians to own their own homes.

Shared Home Ownership

The Shared Home Ownership[5] is the only scheme of its kind in Australia. This scheme is similar to one which was set by the Housing Authority in Malta (Europe). Western Australians can purchase their own home with help from the Department of Housing with a SharedStart loan through Keystart, the Governments lending provider. With shared ownership, the initial cost of buying a home is reduced, as the Department retains up to 30% of the property. The Department's share depends on your borrowing capacity, household size, and the location and type of property. In the future, the buyer may have the option to purchase the full amount or sell the home back to the Department. With a ShareStart loan you can purchase newly built homes and off-the–plan properties offered by the Department of Housing.

Affordable House Sales

The Department of Housing (the Housing Authority), through the Housing Authority, now offers Affordable House Sales[5] to the general public. Properties are available to anyone interested in purchasing a home. The Department works closely with industry to ensure that properties being developed for sale are affordable for those on low-to-moderate incomes.

Canada

In Canada affordability is one of three elements (adequacy, suitability) used to determine core housing needs.[6]

Ontario

In 2002, the Social Housing Services Corporation (SHSC) was created by Province of Ontario to provide group services for social housing providers (public, non-profit and co-op housing) following the downloading of responsibility for over 270,000 social housing units to local municipalities. It is a non-profit corporation governed by a board of municipal, non-profit and co-op housing representatives. Its mandate is to provide Ontario housing providers and service managers with bulk purchasing, insurance, investment and information services that add significant value to their operations.

With an annual budget of $4.5 million, SHSC and its two subsidiaries, SOHO and SHSC Financial Inc. offers a dedicated insurance program for social housing providers, bulk gas purchasing and an innovative energy efficiency retrofit program that coordinates energy audits, expertise, funding, bulk purchasing of energy-efficient goods, training and education, and data evaluation. SHSC manages and provides investment advice to housing providers on capital reserves valued at more than $390 million. Working closely with other housing sector organizations and non-governmental organizations, SHSC also supports and develops independent housing-related research, including a new Housing Internship program for graduate-level researchers.

British Columbia

Recently there has been a move toward the integration of affordable social housing with market housing and other uses, such as the 2006–10 redevelopment of the Woodward's building site in Vancouver.

Legislation to help make home ownership accessible to middle-class families, and other measures aimed to make sure that British Columbians can continue to live, work and raise families in British columbia such as increasing rental property supply was passed and will take effect on August 2, 2016.[7]

China

China is also experiencing a gap between housing price and affordability as it moves away from an in-kind welfare benefit system to a market-oriented allocation system (Hui et al. 2007). Most urban housing prior to 1978 in the planned-economy era consisted of nearly free dwellings produced and allocated by the unsustainable single-channel state-funded system.[8] The goal of China's housing reform started in 1978 was to gradually transform housing from a "free good" to a "subsidized good" and eventually to a "commodity", the price of which reflects true production costs and a market profit margin.[9] In 1998 China accelerated its urban housing reform further moving away from an in-kind welfare benefit system to a market-oriented allocation system, with the state reducing its role in housing provision. The reform is followed by increasing home ownership, housing consumption, real estate investment, as well as skyrocketing housing price.[10]

High housing price is a major issue in a number of big cities in China. Started in 2005, high housing appreciation rate became serious affordability problem for middle and low income families: in 2004 the housing appreciation rate of 17.8%, almost twice the income growth rate 10% (NBSC 2011). Municipal governments have responded to the calling for increase housing supply to middle and low-income families by a number of policies and housing programs, among which are the Affordable Housing Program and the Housing Provident Fund Program.

The Affordable Housing Program (commonly known as the "Economical and Comfortable Housing Program, or 经济适用房) is designed to provide affordable housing to middle- to low-income households to encourage home ownership. In 1998 the Department of Construction and Ministry of Finance jointly promulgated "The Method of Urban Affordable Housing Construction Managing," marked the start of the program. Aimed at middle- to low-income households (annual income less than 30,000 to 70,000 RMB according to size of household and the specific area), this public housing program provides housing (usually 60–110 square meters) at affordable price (usually 50–70% market price).[11]

Within the policies and mandates set by the central government, local governments are responsible for the operation of the program. Local governments usually appropriate state-owned land to real estate developers, who are responsible for the finance and construction of affordable housing.[12] The profit for real estate developers are controlled to be less than 3%,[13] so as to keep the price of housing at the affordable level. Individuals need to apply for the affordable housing through household and income investigation.[14]

The program is controversial in recent years because of insufficient construction, poor administration, and widespread corruption. Local government has limited incentive to provide affordable housing, as it means lower revenue from land-transferring fees and lower local GDP.[15] As a result, the funding of the program has been decreasing ever from its inception, and the affordable housing construction rate dropped from 15.6% (1997) to 5.2% (2008).[16] Because of the limited supply of affordable housing and excessive housing demand from the middle- to low-income populations, affordable housing are usually sold at high market price. In many cities ineligible high-income households own affordable housing units whereas many qualified families are denied access.

Housing Provident Fund (HPF) Program is another policy effort to provide affordable housing. China introduced the Housing Provident Fund (HPF) program nationwide in 1995. It is similar to housing fund programs in other countries such as Thailand and Singapore. HPF provides a mechanism allowing potential purchasers who have an income to save for and eventually purchase a unit dwelling (which may be a formerly public housing unit). The HPF includes a subsidized savings program linked to a retirement account, subsidized mortgage rates and price discounts for housing purchase.[17]

Mali

Development Workshop, a Canadian and French NGO, has brought a real alternative to the inhabitants to accede to affordable housing that fights the environmental degradation and offers training and employment for many people who were under-employed or unemployed. The project has received many awards, such as the UN-Habitat-United Nations Human Settlements Programme award. One of the key aspects of the project is the introduction of a woodless construction and new techniques to build public buildings, offices, and simple shelters among other examples. This process increases the demand for skilled builders, and as a consequence training courses became necessary. The economic cost of the building decreases, and as a result over 1,000 woodless buildings had been built.[18]

India

In India, it is estimated that in 2009–10, approximately 32% of the population was living below the poverty line[19] and there is huge demand for affordable housing. The deficit in Urban housing is estimated at 18 million units most of which are amongst the economically weaker sections of the society. Some developers are developing low cost and affordable housing for this population. The Government of India has taken up various initiatives for developing properties in low cost and affordable segment. They have also looked at PPP model for development of these properties.

The Government of Haryana launched its affordable housing policy in 2013. This policy is intended to encourage the planning and completion of "Group Housing Projects" wherein apartments of pre-defined size are made available at pre-defined rates within a time-frame as prescribed under the present policy to ensure increased supply of Affordable Housing in the urban areas of Haryana. One can get Complete list of Projects [20]here. [21]

Indonesia

Affordable housing in Indonesia called Rumah Subsidi,or for apartement version called Rusunawa.

Republic of Ireland

Affordable housing (Irish: tithíocht inacmhainne) schemes existed until 2011. They offered first-time purchasers the chance to buy newly constructed homes and apartments at prices significantly less than their market value.[22] They have since been replaced by three new schemes:

- Rebuilding Ireland Home Loan (Iasacht Tithíochta Atógáil Éireann): provides mortgages with reduced interest rates (2%–2.25%) to first-time buyers[23]

- Affordable Purchase Scheme: local authorities provide state-owned land at reduced or no cost to developers to facilitate the building of affordable homes

- Affordable Rental Scheme: uses a "cost rental" model to supply low-rent accommodation while still ensuring a small profit for landlords[24]

Philippines

The first affordable housing projects in the Philippines was introduced by then-president Ferdinand Marcos in the 1970s. The Ministry of Human Settlements (now the Department of Human Settlements and Urban Development) established the Bagong Lipunan Improvement of Sites and Services or BLISS. These projects consisted of low-rise apartment buildings with 16 to 32 units each building. These projects were largely abandoned by the government after Marcos was ousted in 1986 and while several sites are still extant, the buildings are generally condemned.[25] Since then, other affordable housing projects were also developed by the National Housing Authority.[26]

The government-owned Bases Conversion and Development Authority (BCDA) is currently developing New Clark City, a new metropolis designed to be "smart, green and disaster-resilient".[27] New Clark City is envisioned to hold over 1.2M people and the BCDA will be building an affordable housing units for its workers.[28]

Turkey

Housing Agency of Turkey (TOKİ) is responsible for construction of houses for lower income. Low income segment houses have longer payments, and generally equal to a month’s rent. Owners are chosen by draw. Applications are limited to people without homes in the same state and limited by monthly income (5,500 TRY as of September 2020).[29] TOKİ also constructs houses without application limits, however these have similar prices with market.

United Kingdom

The British housing market in the late 1980s and early 1990s experienced an almost unprecedented set of changes and pressures. A combination of circumstances produced the crisis, including changes in demography, income distribution, housing supply and tenure, but financial deregulation was particularly important. Housing affordability became a significant policy issue when the impact on the normal functioning of the owner occupied market became severe and when macro-economic feedback effects were perceived as serious. A number of specific policy changes resulted from this crisis, some of which may endure. Many of these revolve around the ability or otherwise of people to afford housing, whether as would-be buyers priced out of the boom, recent buyers losing their home through mortgage default or trapped by 'negative equity', or tenants affected by deregulation and much higher rent levels.[30]

A 2013 investigation by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism found that the UK spent £1.88bn – enough to build 72,000 homes in London – on renting temporary accommodation in 12 of Britain's biggest cities over the preceding four years.[31]

Research by Trust for London and the New Policy Institute found that London delivered 21,500 affordable in the three years up to 2015/16. This was 24% of all homes delivered during that period.[32]

A tradition of social housing in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom has a long tradition of promoting affordable social rented housing. This may be owned by local councils or housing associations. There are also a range of affordable home ownership options, including shared ownership (where a tenant rents part share in the property from a social landlord, and owns the remainder). The government has also attempted to promote the supply of affordable housing principally by using the land-use planning system to require that housing developers provide a proportion of either social or affordable housing within new developments.[33] This approach is known in other countries with formal zoning systems as inclusionary zoning, whilst the current mechanism in the UK is through the use of a S.106 Agreement. In Scotland the equivalent is a Section 75 planning agreement. (Section 75 of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997)

Council houses

A high proportion of homes in the UK were previously council-owned, but the numbers have been reduced since the early 1980s due to initiatives of the Thatcher government that restricted council housing construction and provided financial and policy support to other forms of social housing. In 1980, the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher introduced the Right to Buy scheme, offering council tenants the opportunity to purchase their housing at a discount of up to 60% (70% on leasehold homes such as flats). Alongside Right to Buy, council-owned stock was further diminished as properties were transferred to housing associations. Council Tenants in some instances have chosen to transfer management of the properties to arms-length non-profit organisations. The tenants still remained Council tenants, and the housing stock still remained the property of the Council. This change in management was encouraged by extra funding from central government to invest in the housing stock under the Decent Homes Programme. The program required council housing to be brought up to a set standard was combined with restrictions on the amounts that councils could borrow and led to an increase in such arms length management organisations being set up. In some areas, significant numbers of council houses were demolished as part of urban regeneration programmes, due to the poor quality of stock, low levels of demand and social problems.

In rural areas where local wages are low and house prices are higher (especially in regions with holiday homes), there are special problems. Planning restrictions severely limit rural development, but if there is evidence of need then exception sites can be used for people with a local connection. This evidence is normally provided by a housing Needs survey carried out by a Rural Housing Enabler working for the local Rural Community Council.

Housing associations are not-for-profit organisations with a history that goes back before the start of the 20th century. The number of homes under their ownership grew significantly from the 1980s as successive governments sought to make them the principal form of social housing, in preference to local authorities. Many of the homes previously under the ownership of local authorities have been transferred to newly established housing associations, including some of the largest in the country. Despite being not-for-profit organisations, housing association rents are typically higher than for council housing. Renting a home through a housing association can in some circumstances prove costlier than purchasing a similar property through a mortgage.

All major housing associations are registered with the Homes and Communities Agency who are responsible for the regulation of social housing from 1 April 2012.[34] Housing associations that are registered were known as Registered Social Landlords from 1996, but in the Housing and Regeneration Act 2008 the official term became Registered Providers. The latter also covers council housing, and developers and other bodies that may receive grants for development.[35]:3 The Department for Communities and Local Government sets the policy for housing in England.

In Scotland policy is set by the Scottish Parliament; inspecting and regulating activities falls to the Scottish Housing Regulator.[36] Social housing in Northern Ireland is regulated by the Northern Ireland Housing Executive, which was established to take on ownership of former council stock and prevent sectarian allocation of housing to people from one religion.

A 2017 report by Trust for London and the New Policy Institute found that 24% of new homes built in London were social, affordable or shared ownership accommodation in the three years up to 2015/16.[37]

United States

The federal government in the U.S. provides subsidies to make housing more affordable. Financial assistance is provided for homeowners through the mortgage interest tax deduction and for lower income households through housing subsidy programs. In the 1970s the federal government spent similar amounts on tax reductions for homeowners as it did on subsidies for low-income housing. However, by 2005, tax reductions had risen to $120 billion per year, representing nearly 80 percent of all federal housing assistance.[38] The Advisory Panel on Federal Tax Reform for President Bush proposed reducing the home mortgage interest deduction in a 2005 report.[39]

Housing assistance from the federal government for lower income households can be divided into three parts:

- "Tenant based" subsidies given to an individual household, known as the Section 8 program

- "Project based" subsidies given to the owner of housing units that must be rented to lower income households at affordable rates, and

- Public Housing, which is usually owned and operated by the government. (Some public housing projects are managed by subcontracted private agencies.)

“Project based" subsidies are also known by their section of the U.S. Housing Act or the Housing Act of 1949, and include Section 8, Section 236, Section 221(d)(3), Section 202 for elderly households, Section 515 for rural renters, Section 514/516 for farmworkers and Section 811 for people with disabilities. There are also housing subsidies through the Section 8 program that are project based. The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and USDA Rural Development administer these programs. HUD and USDA Rural Development programs have ceased to produce large numbers of units since the 1980s. Since 1986, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program has been the primary federal program to produce affordable units; however, the housing produced in this program is less affordable than the former HUD programs.

Another program is Inclusionary Housing—an ordinance that requires housing developers to reserve a percentage between 10-30% of housing units from new or rehabilitated projects to be rented or sold at a below market rate for low and moderate-income households.

One of the most unusual US public housing initiatives was the development of subsidized middle-class housing during the late New Deal (1940–42) under the auspices of the Mutual Ownership Defense Housing Division of the Federal Works Agency under the direction of Colonel Lawrence Westbrook. These eight projects were purchased by the residents after the Second World War and as of 2009 seven of the projects continue to operate as mutual housing corporations owned by their residents. These projects are among the very few definitive success stories in the history of the US public housing effort.

In the U.S., households are commonly defined in terms of the amount of realized income they earn relative to the Area Median Income or AMI.[40] Localized AMI figures are calculated annually based on a survey of comparably sized households within geographic ranges known as metropolitan statistical areas, as defined by the US Office of Management and Budget.[41] For U.S. housing subsidies, households are categorized by federal law as follows:[42]

- Moderate income households earn between 80% and 120% of AMI.

- Low income households earn between 50% and 80% of AMI.

- Very low income households earn no more than 50% of AMI.

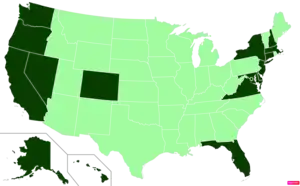

Some states and cities in the United States operate a variety of affordable housing programs, including supportive housing programs, transitional housing programs and rent subsidies as part of public assistance programs. Local and state governments can adapt these income limits when administering local affordable housing programs; however, U.S. federal programs must adhere to the definitions above. For the Section 8 voucher program, the maximum household contribution to rent can be as high as 40% gross income.[43]

Comprehensive data for the most affordable and least affordable places in the U.S. is published each year by an affordable housing non-profit organization, the National Low Income Housing Coalition.[44] The NLIHC promotes a guideline of 30% of household income as the upper limit of affordability. According to a 2012 National Low Income Housing Coalition report, in every community across the United States "rents are unaffordable to full-time working people."[45]

However, by using an indicator, such as the Median Multiple indicator[46] which rates affordability of housing by dividing the median house price by gross [before tax] annual median household income), without considering the extreme disparities between the incomes of high-net-worth individual (HNWI) and those in the lower quintiles, a distorted picture of real affordability is created. Using this indicator—which rates housing affordability on a scale of 0 to 5, with categories 3 and under affordable—in 2012, the United States overall market was considered 3 (affordable).[47]

Since 1996, while incomes in the upper quintile increased, incomes in the lower quintile households decreased creating negative outcomes in housing affordability.[48]

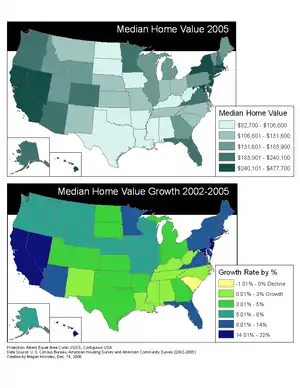

Before the real estate bubble of 2007, the median household paid $658 per month in total housing costs (Census 2002).[49] A total of 20% of households were deemed to be living in unaffordable housing: Nine percent of all households are renters in unaffordable housing,[50] and eleven percent of all households are homeowners with high housing costs.[51]

In the 2000 U.S. Census, the median homeowner with a mortgage (70% of homeowners and 48% of census respondents) spent $1,088 each month, or 21.7% of household income, on housing costs.[52] The median homeowner without a mortgage (30% of all homeowners (80% of elderly homeowners) and 20% of respondents) spent $295 per month, or 10.5% of household income, on housing costs.[52] Renters in 2001 (32% of respondents) spent $633 each month, or 29% of household income, on housing costs.[53]

Governmental and quasi-governmental agencies that contribute to the work of ensuring the existence of a steady supply of affordable housing in the United States are the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), USDA Rural Development, the Federal Home Loan Bank, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac. Housing Partnership Network is an umbrella organization of 100+ housing and community development nonprofits. Important private sector institutions worth consulting are the National Association of Home Builders, the National Affordable Housing Management Association (NAHMA), the Council for Affordable and Rural Housing (CARH) and the National Association of Realtors. Valuable research institutions with staff dedicated to the analysis of "affordable housing" includes: The Center for Housing Policy, Brookings Institution, the Urban Institute and the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University and the Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy at New York University, and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Several of these institutions (the Fannie Mae Foundation, Urban Institute, Brookings Institution Metropolitan Policy Program, Enterprise Community Partners, LISC, the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, and others)[54] partnered to create KnowledgePlex, an online information resource devoted to affordable housing and community development issues.

New York City

New York City has a shortage of affordable housing resulting in overcrowding and homelessness. New York City attracts thousands of new residents each year and housing prices continue to climb. Finding affordable housing affects a large portion of the city’s population including low-income, moderate-income, and even median income families.[55] Since 1970, income has remained stagnant while rent has nearly doubled for New Yorkers.[55] Consequently, 48.7% of householders spend more than 30% of their income on rent.[55] Several federal and state initiatives have targeted this problem, but have failed to provide enough affordable, inclusive, and sustainable housing for New York City residents.

City of San Diego

San Diego's housing crisis is largely driven by the cost of the housing, rather than a shortage of housing units. According to the Housing and Urban Development, total housing costs are affordable if they meet or are below 30% of annual income.[56] According to the American Community Survey of 2016, 54.8% of renters in San Diego pay 30% or over of their income toward rent and housing costs every month.[57] Even with an estimated 84,000 vacant housing units,[58] a significant number of people choose to live outside of county lines, where housing costs are lower. About twenty percent of San Diego workers live outside the county, notably in Riverside County, where median home costs can be as much as $195,400 cheaper.[59] However, where housing costs may be lower, these workers are now facing longer commutes. The combination of housing costs and transport costs means that as many as 45% of the population working in San Diego face poverty.[60]

Homelessness is a huge challenge also stemming from this lack of affordable housing. The Regional Task Force on the Homeless counted 4,912 homeless individuals in the City of San Diego alone, with 8,576 homeless persons in the San Diego region.[61] Multiple propositions have been made to abate the problem. In 2018, California voted on Prop 10, which would have lifted state regulations on rent control and allowed local jurisdictions to set their own policies. It did not pass.[62] More recently, in March 2019, the San Diego City Council voted and approved a reform to parking standards on housing units near public transit with the goal of reducing housing costs associated with mandated parking spots and relieve traffic by encouraging residents to use public transit.[63]

Subsidized housing programs

The Department of Housing and Urban Development's Section 8 programs help low income citizens find housing by paying the difference between the market price of a home and 30% of the renter's income.[64] According to the San Diego Housing Commission, Section 8 housing vouchers are the city's largest affordable housing program and were responsible for helping to fill 14,698 homes in the 2014-2015 fiscal year.[65] The San Diego Housing Commission currently owns 2,221 affordable housing units and plans to expand that number in the future to meet the growing demand.[66]

Recent policies to create more affordable housing

In 2009, the San Diego Housing Commission implemented a finance plan that created 810 more units of affordable rental housing through leveraging the equity of its owned properties. The conversion of city-owned buildings into low-income affordable housing was made possible by an agreement made with the Department of Housing and Urban Development in September 2007. The cost of rent and availability of these units for residents will remain consistent, as the city has put in place provisions to make them affordable for at least 55 years. Additionally, because of a concern that the people who need these housing units might be crowded out, the units are only available to residents with an income cap of 80% of the San Diego median.[67]

In 2017, the new Atmosphere building downtown drew attention when it announced that it would be offering 205 apartments to low-income San Diego residents.[68] Residents pay their portion of rent through Section 8 vouchers, and many of the apartments are available only to families who make 30% or less of the median income of the city.[69] The main idea behind the new housing project was to provide a low-rent area for residents who work downtown but who are unable to live near their workplace because of the high costs.[68]

Grand County, Colorado

Affordable housing is a problem that is affecting people nationwide, including Grand County, Colorado. According to research by Rubin and Ponser (2018), “In 2016, the median renter in the bottom quartile had only $488 left per month after rent for essentials like food, health care, utilities, and transportation” (para. 4). A lack of affordable housing can be a serious problem for people, as overpaying for housing leaves families with little leftover to spend on other essentials like food and clothing. Grand County could benefit from increasing the amount of affordable housing that is available in the area. The increase of housing would allow local families to rent housing at a more affordable price, hopefully reducing stress for people. It would also attract new people to the area and provide jobs for local companies that build the housing, helping to stimulate the local economy. The increased housing would also help local businesses by making more housing available for workers. Overall, the housing could help Grand County and its residents to be a more livable and profitable community.[70]

Housing Prices in Colorado

Colorado has seen a unique problem in housing crisis due to an imbalance in supply and demand but specifically it has been tied to supply of affordable housing to meet the demands. Colorado Springs alone is expected to hit shortages in housing of 26,000 units by 2019 and the builders are simply unable to meet the demands.[71] The important thing to note is that the situation in Colorado is unique because it isn't the lack of supply driving up the prices, but Colorado has a lack of supply specifically in affordability. Colorado has one of the slowest markets for houses in the upper price rangers, and one of the fastest in the affordable index. The state is also plagued with one of the slowest build rates in the United States due to state's strict zoning laws around the metropolitan areas and a slow network of suppliers.[72] Another strong issue to consider is the lack of ease and increasing costs of building homes. With tight margins for profits, it is difficult for builders to justify building large volumes of affordable homes instead of building luxury homes.[73] The state government has acknowledged this problem and has decided to continue to work with builders in providing incentives to building a diverse range of homes in terms of pricing. The legislation and loosening the boundaries will need to come with some form of checks and balances to ensure that builders are utilizing it for its intended purpose of providing affordable housing and not simply continue the trend for housing.

The argument consisting of alerting potential buyers of a 'bubble' in Colorado is false. A bubble for housing market is formed when there is an overabundance of supplies yet increasing prices. Colorado does not have this issue, rather it has significant amount of homes for sale, just not enough buyers in all segments and yet the housing prices have continued to increase. The number of buyers has continued to trend down, and the prices of homes has continued to trend up.[73] The increase in house prices are thus not at any risk of a bubble, rather the resolution to this issue is, as mentioned above, an intervention from the state to either provide legislative mandates to diversify the homes being built to price points with a special focus on affordability or provide incentives to builders to continue building affordable housing. The concerns with supplies will also need to be tackled, but all of these issues ultimately do rest on the state performing certain actions to change the portfolio of homes in Colorado.

References

- Bhatta, Basudeb (15 April 2010). Analysis of Urban Growth and Sprawl from Remote Sensing Data. Advances in Geographic Information Science. Springer. p. 23. ISBN 978-3-642-05298-9.

- Centrelink (30 June 2008). "Eligibility for Rent Assistance". Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- "First Home Owners Scheme". Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- Australian Taxation Office (October 2008). "The First Home Saver Account: What you need to know" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- "Opening Doors to Affordable Housing". www.openingdoorswa.com.au.

- Canada Mortgage; Housing Corporation (28 September 2011). "Affordable Housing: What is the common definition of affordability?". Government of Canada. Archived from the original (.cfm) on 7 May 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- Premier, Office of the (2016-07-25). "Action on foreign investment, consumer protection and vacancy puts British Columbians first - BC Gov News". news.gov.bc.ca. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- Mostafa, Anirban; Wong, Francis K. W.; Hui, Chi Mun Eddie (2006). "Relationship between Housing Affordability and Economic Development in Mainland China—Case of Shanghai". Journal of Urban Planning and Development. 132 (62): 9. doi:10.1061/(asce)0733-9488(2006)132:1(62). hdl:10397/20905.

- Chiu, Rebecca (1996). "Housing affordability in Shenzhen special economic zone: A forerunner of China's housing reform". Housing Studies. 11 (4): 561–580. doi:10.1080/02673039608720875.

- Gao, Lu (April 1, 2010). "Achievements and Challenges: 30 Years of Housing Reforms in the People's Republic of China". Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series No. 198. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1619161. hdl:10419/128508. S2CID 166763911. SSRN 1619161. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - The Chinese Ministry of Construction. Urban Affordable Housing Construction Policing method.

- Man, Joyce Yanyun. "Affordable Housing in China". LILP.

- The State Council housing organizational reform leading group in China. Affordable Housing Management Method.

- "Application for Affordable Housing".

- Palomar, Joyce; Lou, Jianbo (2007). Housing Policy in the People's Republic of China: Successes and Disappointments (Report).

- "中国统计年鉴-2011". www.stats.gov.cn. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- Buttimer, Richard J. (2004). "The Chinese Housing Provident Fund" (PDF). International Real Estate Review. 7 (1). p. 30. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- "Training and employment of locals. [Social Impact]. WConstruction. The promotion of Woodless Construction in West Africa (1980-2017)". SIOR, Social Impact Open Repository.

- World Bank. India Country Overview September 2011. 32% is the 2009–10 estimate, down from 37% in 2004–05.

- https://realyards.com/affordable/affordable-housing-projects-in-gurgaon/

- "Haryana Government - notification" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- Citizensinformation.ie. "Affordable housing schemes". www.citizensinformation.ie.

- "Information booklet" (PDF). rebuildingirelandhomeloan.ie.

- "New affordable housing schemes - What's New". whatsnew.citizensinformation.ie. Archived from the original on 2018-09-02. Retrieved 2018-11-03.

- Marcelino, Louise. Spaces of BLISS and BLISS Market (PDF) (Thesis). University of the Philippines Vargas Museum. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- "The Integration of the Relocatees into the Community of Dasmariñas: An Overview". Nilo D. Cabides, PhD of De La Salle University- Dasmariñas. Archived from the original on 2010-10-21. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- "New Clark City". Bases Conversion and Development Authority. December 13, 2018. Retrieved 2020-09-29.

- "UK gov't, BCDA partner on New Clark City Central Park, affordable housing project". Philippine Information Agency. Republic of the Philippines. September 21, 2020. Retrieved 2020-09-29.

- "TOKİ Housing Programs". toki.gov.tr. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- Bramley, Glen (1994). "An affordability crisis in British housing: dimensions, causes and policy impact". Housing Studies. 9 (1): 103–124. doi:10.1080/02673039408720777.

- Mathiason, Nick; Hollingsworth, Victoria; Fitzgibbon, Will. 'Scale of UK housing crisis revealed', The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, 19 May 2013.

- "London's Poverty Profile 2017". Trust for London. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Planning Policy Statement No. 3: Housing, Department of Communities and Local Government 2006

- "Tenant Services Authority". Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- Affordable Housing – a new dawn?, Jones Lang LaSalle, 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- "Regulating to protect the interests of tenants, homeless people and others who use social landlords' services". Scottish Housing Regulator. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- "London's Poverty Profile 2017". Trust for London. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- "Changing priorities" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- "President's Advisory Panel on Federal Tax Reform". Archived from the original on 15 March 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- "Initiative for Affordable Housing – Glossary". Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas". Archived from the original on 21 February 1999. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- "Public Housing/Section 8 Income Limits for FY 1999". Archived from the original on 3 April 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- "Housing Choice Vouchers Fact Sheet – HUD". Archived from the original on 18 March 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- "NLIHC: National Low Income Housing Coalition – Out of Reach 2006". Archived from the original on 5 October 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- National Low Income Housing Coalition (13 March 2012). Out of Reach 2012: America's Forgotten Housing Crisis (Report).

- Wendell Cox; Hugh Pavletich (2012). 8th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: 2012 Ratings for Metropolitan Markets (Report). p. 1.

- Wendell Cox; Hugh Pavletich (2012). 8th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: 2012 Ratings for Metropolitan Markets (Report). p. 16.

- Matlack, Janna L.; Vigdor, Jacob L. (2008). "Do Rising Tides Lift All Prices? Income Inequality and Housing Affordability" (PDF). Journal of Housing Economics. 17 (3): 212–224. doi:10.1016/j.jhe.2008.06.004.

- Table 1A-7: Financial Characteristics All Housing Units"American Housing Survey for the United States: 2001" (PDF). Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- Calculated as percentage of renter households multiplied by percentage of renter households that are burdened by housing costs in excess of 30%"Renter Households Data" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- Calculated as percentage of owner-occupied households multiplied by percentage with a mortgage multiplied by percentage of those with a mortgage who are burdened by housing costs in excess of 30%."Owner Households Data" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- "United States – QT-H15. Mortgage Status and Selected Monthly Owner Costs:2000". Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- "American Housing Survey – Frequently Asked Questions". Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- Partners Archived 16 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "State of New York City’s Subsidized Housing: 2011." New York: Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, The Institute for Affordable Housing.

- Hamidi, Shima; Ewing, Reid; Renne, John (3 May 2016). "How Affordable Is HUD Affordable Housing?". Housing Policy Debate. 26 (3): 437–455. doi:10.1080/10511482.2015.1123753. S2CID 73663740.

- "ACS 2016 (1-Year Estimates)". Social Explorer. Retrieved 2019-03-06.

- U.S. Census Bureau. "Selected Housing Characteristics 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". American Factfinder. Archived from the original on 2020-02-14. Retrieved 2019-03-06.

- Service, City News. "San Diego County To Study Affordable Housing Solutions". KPBS Public Media. Retrieved 2019-03-06.

- "A Renewed Struggle for the American Dream: PRRI 2018 California Workers Survey". PRRI. Retrieved 2019-03-06.

- Regional Task Force on the Homeless (May 17, 2018). "2018 WeAllCount Annual Report San Diego County".

- "Proposition 10 | Official Voter Information Guide | California Secretary of State". www.voterguide.sos.ca.gov. Retrieved 2019-03-06.

- "Mayor Faulconer's Parking Reforms Win City Council Approval" (Press release). City of San Diego. 4 March 2019.

- Hamidi, Shima; Ewing, Reid; Renne, John. "How Affordable is HUD Affordable Housing?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-16. Retrieved 2018-11-03.

- "San Diego Housing Commission Rental Assistance". San Diego Housing Commission. Archived from the original on 2018-06-16. Retrieved 2018-11-03.

- "Affordable Housing Programs". San Diego Housing Commission.

- "Creating Affordable Housing". San Diego Housing Commission. Archived from the original on 2018-06-14. Retrieved 2018-11-03.

- Molnar, Phillip. "Living in downtown San Diego with a Balcony- for $525 a month". San Diego Union Tribune.

- "A New Atmosphere in San Diego". Corporation for Supportive Housing. 2015-03-25. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- Rubin, Roberta; Ponsor, Andrea (2018). "Affordable Housing and Resident Health". Journal of Affordable Housing & Community Development Law. 27 (2): 263–317. ProQuest 2110277581.

- Walton, Lisa. "Economist: No quick fix for affordable housing crisis plaguing Colorado, rest of nation". Colorado Politics. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- Vick, Marjie (6 August 2018). "The New Housing Crisis: Shut Out Of The Market". NPR.org.

- Oliner, Stephen D. (1 July 2016). "Housing Conundrum: A Shortage of Demand or Supply?". Business Economics. 51 (3): 161–165. doi:10.1057/s11369-016-0003-3. S2CID 157211312.

External links

- Aalbers, Manuel B. (2015). "The Great Moderation, the Great Excess and the Global Housing Crisis". International Journal of Housing Policy. 15 (1): 43–60. doi:10.1080/14616718.2014.997431. S2CID 153584502.

- "Policies to promote access to good-quality affordable housing in OECD countries". OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers. 2016. doi:10.1787/5jm3p5gl4djd-en. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Fields, Desiree; Uffer, Sabina (31 July 2014). "The financialisation of rental housing: A comparative analysis of New York City and Berlin". Urban Studies. 53 (7): 1486–1502. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.836.5392. doi:10.1177/0042098014543704. S2CID 155800842.