Fannie Mae

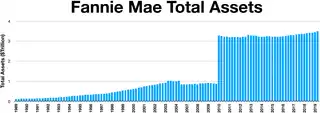

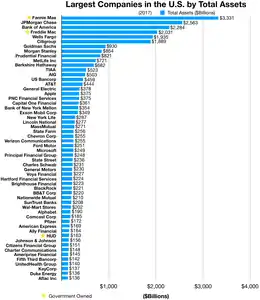

The Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA), commonly known as Fannie Mae, is a United States government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) and, since 1968, a publicly traded company. Founded in 1938 during the Great Depression as part of the New Deal,[2] the corporation's purpose is to expand the secondary mortgage market by securitizing mortgage loans in the form of mortgage-backed securities (MBS),[3] allowing lenders to reinvest their assets into more lending and in effect increasing the number of lenders in the mortgage market by reducing the reliance on locally based savings and loan associations (or "thrifts").[4] Its sister organization is the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (FHLMC), better known as Freddie Mac. As of 2018, Fannie Mae is ranked number 21 on the Fortune 500 rankings of the largest United States corporations by total revenue.[5]

| |

Fannie Mae's former headquarters at 3900 Wisconsin Avenue, NW in Washington, D.C. | |

| Type | Government-sponsored enterprise and public company |

|---|---|

| OTCQB: FNMA | |

| Industry | Financial services |

| Founded | 1938 |

| Headquarters | Midtown Center, 1100 15th Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20005 |

Key people | Sheila Bair[1] (Chairman) Hugh R. Frater (Chief Executive Officer) Celeste M. Brown (Senior Executive Vice President and CFO) David C. Benson (President) |

| Products | Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | ~7,500 (December 31, 2019) |

| Website | www |

| Footnotes / references https://www.fanniemae.com/resources/file/ir/pdf/quarterly-annual-results/2019/q42019.pdf | |

History

Historically, most housing loans in the early 1900s in the USA were short term mortgage loans with balloon payments.[6] The Great Depression wrought havoc on the U.S. housing market as people lost their jobs and were unable to make payments. By 1933, an estimated 20 to 25% of the nation's outstanding mortgage debt was in default.[7] This resulted in foreclosures in which nearly 25% of America's homeowners lost their homes to banks. To address this, Fannie Mae was established by the U.S. Congress in 1938 by amendments to the National Housing Act[8] as part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal. Originally chartered as the National Mortgage Association of Washington, the organization's explicit purpose was to provide local banks with federal money to finance home loans in an attempt to raise levels of home ownership and the availability of affordable housing.[9] Fannie Mae created a liquid secondary mortgage market and thereby made it possible for banks and other loan originators to issue more housing loans, primarily by buying Federal Housing Administration (FHA) insured mortgages.[10] For the first thirty years following its inception, Fannie Mae held a monopoly over the secondary mortgage market.[9] Other considerations may have motivated the New Deal focus on the housing market: about a third of the nation's unemployed were in the building trade, and the government had a vested interest in getting them back to work by giving them homes to build.[11]

Fannie Mae was acquired by the Housing and Home Finance Agency from the Federal Loan Agency as a constituent unit in 1950.[12] In 1954, an amendment known as the Federal National Mortgage Association Charter Act[13] made Fannie Mae into "mixed-ownership corporation", meaning that federal government held the preferred stock while private investors held the common stock;[8] in 1968 it converted to a privately held corporation, to remove its activity and debt from the federal budget.[14] In the 1968 change, arising from the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968, Fannie Mae's predecessor (also called Fannie Mae) was split into the current Fannie Mae and the Government National Mortgage Association ("Ginnie Mae").

Ginnie Mae, which remained a government organization, guarantees FHA-insured mortgage loans as well as Veterans Administration (VA) and Farmers Home Administration (FmHA) insured mortgages. As such, Ginnie Mae is the only home-loan agency explicitly backed by the full faith and credit of the United States government.[15]

In 1970, the federal government authorized Fannie Mae to purchase conventional loans, i.e. those not insured by the FHA, VA, or FmHA, and created the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (FHLMC), colloquially known as Freddie Mac, to compete with Fannie Mae and thus facilitate a more robust and efficient secondary mortgage market.[15] That same year FNMA went public on New York and Pacific Exchanges.[16]

In 1981, Fannie Mae issued its first mortgage passthrough and called it a mortgage-backed security. Ginnie Mae had guaranteed the first mortgage passthrough security of an approved lender in 1968[17] and in 1971 Freddie Mac issued its first mortgage passthrough, called a participation certificate, composed primarily of private mortgage loans.[17]

1990s

In 1992, President George H.W. Bush signed the Housing and Community Development Act of 1992.[18] The Act amended the charter of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to reflect the Democratic Congress' view that the GSEs "have an affirmative obligation to facilitate the financing of affordable housing for low- and moderate-income families in a manner consistent with their overall public purposes, while maintaining a strong financial condition and a reasonable economic return".[19] For the first time, the GSEs were required to meet "affordable housing goals" set annually by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and approved by Congress. The initial annual goal for low-income and moderate-income mortgage purchases for each GSE was 30% of the total number of dwelling units financed by mortgage purchases[20] and increased to 55% by 2007.

In 1999, Fannie Mae came under pressure from the Clinton administration to expand mortgage loans to low and moderate income borrowers by increasing the ratios of their loan portfolios in distressed inner city areas designated in the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) of 1977.[21] In 1999, The New York Times reported that with the corporation's move towards the subprime market "Fannie Mae is taking on significantly more risk, which may not pose any difficulties during flush economic times. But the government-subsidized corporation may run into trouble in an economic downturn, prompting a government rescue similar to that of the savings and loan industry in the 1980s."[22]

2000s

In 2000, because of a re-assessment of the housing market by HUD, anti-predatory lending rules were put into place that disallowed risky, high-cost loans from being credited toward affordable housing goals. In 2004, these rules were dropped and high-risk loans were again counted toward affordable housing goals.[24]

The intent was that Fannie Mae's enforcement of the underwriting standards they maintained for standard conforming mortgages would also provide safe and stable means of lending to buyers who did not have prime credit. As Daniel Mudd, then president and CEO of Fannie Mae, testified in 2007, instead the agency's underwriting requirements drove business into the arms of the private mortgage industry who marketed aggressive products without regard to future consequences:

We also set conservative underwriting standards for loans we finance to ensure the homebuyers can afford their loans over the long term. We sought to bring the standards we apply to the prime space to the subprime market with our industry partners primarily to expand our services to underserved families. Unfortunately, Fannie Mae-quality, safe loans in the subprime market did not become the standard, and the lending market moved away from us. Borrowers were offered a range of loans that layered teaser rates, interest-only, negative amortization and payment options and low-documentation requirements on top of floating-rate loans. In early 2005 we began sounding our concerns about this "layered-risk" lending. For example, Tom Lund, the head of our single-family mortgage business, publicly stated, "One of the things we don't feel good about right now as we look into this marketplace is more homebuyers being put into programs that have more risk. Those products are for more sophisticated buyers. Does it make sense for borrowers to take on risk they may not be aware of? Are we setting them up for failure? As a result, we gave up significant market share to our competitors."[25]

Alex Berenson of The New York Times reported in 2003 that Fannie Mae's risk was much larger than was commonly believed.[26] Nassim Taleb wrote in The Black Swan: "The government-sponsored institution Fannie Mae, when I look at its risks, seems to be sitting on a barrel of dynamite, vulnerable to the slightest hiccup. But not to worry: their large staff of scientists deem these events 'unlikely'".[27]

On January 26, 2005, the Federal Housing Enterprise Regulatory Reform Act of 2005 (S.190) was first introduced in the Senate by Sen. Chuck Hagel.[28] The Senate legislation was an effort to reform the existing GSE regulatory structure in light of the recent accounting problems and questionable management actions leading to considerable income restatements by the GSEs. After being reported favorably by the Senate's Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs in July 2005, the bill was never considered by the full Senate for a vote.[29] Sen. John McCain's decision to become a cosponsor of S.190 almost a year later in 2006 was the last action taken regarding Sen. Hagel's bill in spite of developments since clearing the Senate Committee. Sen. McCain pointed out that Fannie Mae's regulator reported that profits were "illusions deliberately and systematically created by the company's senior management" in his floor statement giving support to S.190.[30][31]

At the same time, the House also introduced similar legislation, the Federal Housing Finance Reform Act of 2005 (H.R. 1461), in the Spring of 2005. The House Financial Services Committee had crafted changes and produced a Committee Report by July 2005 to the legislation. It was passed by the House in October in spite of President Bush's statement of policy opposed to the House version, which stated: "The regulatory regime envisioned by H.R. 1461 is considerably weaker than that which governs other large, complex financial institutions."[32] The legislation met with opposition from both Democrats and Republicans at that point and the Senate never took up the House passed version for consideration after that.[33]

The mortgage crisis from late 2007

Following their mission to meet federal Housing and Urban Development (HUD) housing goals, GSEs such as Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBanks) had striven to improve home ownership of low and middle income families, underserved areas, and generally through special affordable methods such as "the ability to obtain a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage with a low down payment... and the continuous availability of mortgage credit under a wide range of economic conditions".[34] Then in 2003–2004, the subprime mortgage crisis began.[35] The market shifted away from regulated GSEs and radically toward Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS) issued by unregulated private-label securitization (PLS) conduits, typically operated by investment banks.

As loan originators began to distribute more and more of their loans through private label PLS's, the GSEs lost the ability to monitor and control loan originators. Competition between the GSEs and private securitizers for loans further undermined GSEs' power and strengthened mortgage originators. This contributed to a decline in underwriting standards and was a major cause of the financial crisis.

Investment bank securitizers were more willing to securitize risky loans because they generally retained minimal risk. Whereas the GSEs guaranteed the performance of their mortgage-backed securities (MBSs), private securitizers generally did not, and might only retain a thin slice of risk. Often, banks would offload this risk to insurance companies or other counterparties through credit default swaps, making their actual risk exposures extremely difficult for investors and creditors to discern.

The shift toward riskier mortgages and private label MBS distribution occurred as financial institutions sought to maintain earnings levels that had been elevated during 2001–2003 by an unprecedented refinancing boom due to historically low interest rates. Earnings depended on volume, so maintaining elevated earnings levels necessitated expanding the borrower pool using lower underwriting standards and new products that the GSEs would not (initially) securitize. Thus, the shift away from GSE securitization to private-label securitization (PLS) also corresponded with a shift in mortgage product type, from traditional, amortizing, fixed-rate mortgages (FRMs) to nontraditional, structurally riskier, nonamortizing, adjustable-rate mortgages (ARM's), and in the start of a sharp deterioration in mortgage underwriting standards.[35] The growth of PLS, however, forced the GSEs to lower their underwriting standards in an attempt to reclaim lost market share to please their private shareholders. Shareholder pressure pushed the GSEs into competition with PLS for market share, and the GSEs loosened their guarantee business underwriting standards in order to compete. In contrast, the wholly public FHA/Ginnie Mae maintained their underwriting standards and instead ceded market share.[35]

The growth of private-label securitization and lack of regulation in this part of the market resulted in the oversupply of underpriced housing finance[35] that led, in 2006, to an increasing number of borrowers, often with poor credit, who were unable to pay their mortgages – particularly with adjustable rate mortgage loans (ARM), caused a precipitous increase in home foreclosures. As a result, home prices declined as increasing foreclosures added to the already large inventory of homes and stricter lending standards made it more and more difficult for borrowers to get loans. This depreciation in home prices led to growing losses for the GSEs, which back the majority of US mortgages. In July 2008, the government attempted to ease market fears by reiterating their view that "Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac play a central role in the US housing finance system". The US Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve took steps to bolster confidence in the corporations, including granting both corporations access to Federal Reserve low-interest loans (at similar rates as commercial banks) and removing the prohibition on the Treasury Department to purchase the GSEs' stock. Despite these efforts, by August 2008, shares of both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had tumbled more than 90% from their one-year prior levels.

On October 21, 2010 FHFA estimates revealed that the bailout of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae will likely cost taxpayers $224–360 billion in total, with over $150 billion already provided.[36]

2008 – crisis and conservatorship

On July 11, 2008, The New York Times reported that U.S. government officials were considering a plan for the U.S. government to take over Fannie Mae and/or Freddie Mac should their financial situations worsen due to the U.S. housing crisis.[37] Fannie Mae and smaller Freddie Mac owned or guaranteed a massive proportion of all home loans in the United States and so were especially hard hit by the slump. The government officials also stated that the government had also considered calling for explicit government guarantee through legislation of $5 trillion on debt owned or guaranteed by the two companies.

Fannie stock plunged.[38] Some worried that Fannie lacked capital and might go bankrupt. Others worried about a government seizure. U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry M. Paulson as well as the White House went on the air to defend the financial soundness of Fannie Mae, in a last-ditch effort to prevent a total financial panic.[39][40] Fannie and Freddie underpinned the whole U.S. mortgage market. As recently as 2008, Fannie Mae and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) had owned or guaranteed about half of the U.S.'s $12 trillion mortgage market.[37] If they were to collapse, mortgages would be harder to obtain and much more expensive. Fannie and Freddie bonds were owned by everyone from the Chinese Government, to money market funds, to the retirement funds of hundreds of millions of people. If they went bankrupt there would be mass upheaval on a global scale.[41]

The Administration PR effort was not enough, by itself, to save the GSEs. Their government directive to purchase bad loans from private banks, in order to prevent these banks from failing, as well as the 20 top banks falsely classifying loans as AAA, caused instability. Paulson's plan was to go in swiftly and seize the two GSEs, rather than provide loans as he did for AIG and the major banks; he told president Bush that "the first sound they hear will be their heads hitting the floor", in a reference to the French revolution.[41] The major banks have since been sued by the Feds for a sum of $200,000,000, and some of the major banks have already settled.[42] In addition, a lawsuit has been filed against the federal government by the shareholders of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, for a) creating an environment by which Fannie and Freddie would be unable to meet their financial obligations b) forcing the executive management to sign over the companies to the conservator by (a), and c) the gross violation of the (fifth amendment) taking clause.

On September 7, 2008, James Lockhart, director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), announced that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were being placed into conservatorship of the FHFA. The action was "one of the most sweeping government interventions in private financial markets in decades".[43][44][45] Lockhart also dismissed the firms' chief executive officers and boards of directors, and caused the issuance to the Treasury new senior preferred stock and common stock warrants amounting to 79.9% of each GSE. The value of the common stock and preferred stock to pre-conservatorship holders was greatly diminished by the suspension of future dividends on previously outstanding stock, in the effort to maintain the value of company debt and of mortgage-backed securities. FHFA stated that there are no plans to liquidate the company.[43][44][45][46][47][48][49]

The authority of the U.S. Treasury to advance funds for the purpose of stabilizing Fannie Mae, or Freddie Mac is limited only by the amount of debt that the entire federal government is permitted by law to commit to. The July 30, 2008 law enabling expanded regulatory authority over Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac increased the national debt ceiling US$800 billion, to a total of US$10.7 Trillion in anticipation of the potential need for the Treasury to have the flexibility to support the federal home loan banks.[50][51][52]

2010 – delisting

On June 16, 2010, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac announced their stocks would be delisted from the NYSE. The Federal Housing Finance Agency directed the delisting after Fannie's stock traded below $1 a share for over 30 days. Since then the stocks have continued to trade on the Over-the-Counter Bulletin Board.[53]

2013 – $59.39 billion dividend

In May 2013, Fannie Mae announced that it is going to pay a dividend of $59.4 billion to the United States Treasury.[54]

2014 – $134.5 billion dividend paid

Fannie Mae's 2014 financial results enabled it to pay $20.6 billion in dividends to Treasury for the year, resulting in a cumulative total of $134.5 billion in dividends through December 31, 2014 – approximately $18 billion more than Fannie Mae received in support. As of March 31, 2015, Fannie Mae expects to have paid a total of $136.4 billion in payments to the Treasury.[57][58][59][60]

Business

Fannie Mae makes money partly by borrowing at low rates, and then reinvesting its borrowings into whole mortgage loans and mortgage backed securities. It borrows in the debt markets by selling bonds, and provides liquidity to loan originators by purchasing whole loans. It purchases whole loans and then securitizes them for the investment market by creating MBS that are either retained or sold.

As a Government Sponsored Enterprise, or GSE, Fannie Mae is compelled by law to provide liquidity to loan originators in all economic conditions. It must legally ignore adverse market conditions which appear to be unprofitable. If there are loans available for purchase that meet its predetermined underwriting standards, it must purchase them if no other buyers are available. Because of the size, scale, and scope of the United States single-family residential and commercial residential markets, market participants viewed Fannie Mae corporate debt as having a very high probability of being repaid. Fannie Mae is able to borrow very inexpensively in the debt markets as a consequence of market perception. There usually exists a large difference between the rate at which it can borrow and the rate at which it can 'lend'. This was called "The big, fat gap" by Alan Greenspan.[61] By August 2008, Fannie Mae's mortgage portfolio was in excess of $700 billion.

Fannie Mae also earns a significant portion of its income from guaranty fees it receives as compensation for assuming the credit risk on mortgage loans underlying its single-family Fannie Mae MBS and on the single-family mortgage loans held in its retained portfolio. Investors, or purchasers of Fannie Mae MBSs, are willing to let Fannie Mae keep this fee in exchange for assuming the credit risk; that is, Fannie Mae's guarantee that the scheduled principal and interest on the underlying loan will be paid even if the borrower defaults.

Fannie Mae's charter has historically prevented it from guaranteeing loans with a loan-to-values over 80% without mortgage insurance or a repurchase agreement with the lender;[8] however, in 2006 and 2007 Fannie Mae did purchase subprime and Alt-A loans as investments.[62]

Business mechanism

Fannie Mae is a purchaser of mortgages loans and the mortgages that secure them, which it packages into mortgaged-backed securities (MBS). Fannie Mae buys loans from approved mortgage sellers and securitizes them; it then sells the resultant mortgage-backed security to investors in the secondary mortgage market, along with a guarantee that the stated principal and interest payments will be timely passed through to the investor.. In addition, Fannie MBS, like those of Freddie Mac MBS and Ginnie Mae MBS, are eligible to be traded in the "to-be-announced," or "TBA" market.[63] By purchasing the mortgages, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac provide banks and other financial institutions with fresh money to make new loans. This gives the United States housing and credit markets flexibility and liquidity.[64]

In order for Fannie Mae to provide its guarantee to mortgage-backed securities it issues, it sets the guidelines for the loans that it will accept for purchase, called "conforming" loans. Fannie Mae produced an automated underwriting system (AUS) tool called Desktop Underwriter (DU) which lenders can use to automatically determine if a loan is conforming; Fannie Mae followed this program up in 2004 with Custom DU, which allows lenders to set custom underwriting rules to handle nonconforming loans as well.[65] The secondary market for nonconforming loans includes jumbo loans, which are loans larger than the maximum that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac will purchase. In early 2008, the decision was made to allow TBA (To-be-announced)-eligible mortgage-backed securities to include up to 10% "jumbo" loans.[66]

Conforming loans

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have a limit on the maximum sized loan they will guarantee. This is known as the "conforming loan limit". The conforming loan limit for Fannie Mae, along with Freddie Mac, is set by Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight (OFHEO), the regulator of both GSEs. OFHEO annually sets the limit of the size of a conforming loan based on the October to October changes in mean home price, above which a mortgage is considered a non-conforming jumbo loan. The conforming loan limit is 50 percent higher in Alaska and Hawaii. The GSEs only buy loans that are conforming to repackage into the secondary market, lowering the demand for non-conforming loans. By virtue of the law of supply and demand, then, it is harder for lenders to sell these loans in the secondary market; thus these types of loans tend to cost more to borrowers (typically 1/4 to 1/2 of a percent). Indeed, in 2008, since the demand for bonds not guaranteed by GSEs was almost non-existent, non-conforming loans were priced nearly 1% to 1.5% higher than conforming loans.

Implicit guarantee and government support

Originally, Fannie had an 'explicit guarantee' from the government; if it got in trouble, the government promised to bail it out. This changed in 1968. Ginnie Mae was split off from Fannie. Ginnie retained the explicit guarantee. Fannie, however, became a private corporation, chartered by Congress and with a direct line of credit to the US Treasury. It was its nature as a Government Sponsored Enterprise (GSE) that provided the 'implied guarantee' for their borrowing. The charter also limited their business activity to the mortgage market. In this regard, although they were a private company, they could not operate like a regular private company.

Fannie Mae received no direct government funding or backing; Fannie Mae securities carried no actual explicit government guarantee of being repaid. This was clearly stated in the law that authorizes GSEs, on the securities themselves, and in many public communications issued by Fannie Mae. Neither the certificates nor payments of principal and interest on the certificates were explicitly guaranteed by the United States government. The certificates did not legally constitute a debt or obligation of the United States or any of its agencies or instrumentalities other than Fannie Mae. During the sub-prime era, every Fannie Mae prospectus read in bold, all-caps letters: "The certificates and payments of principal and interest on the certificates are not guaranteed by the United States, and do not constitute a debt or obligation of the United States or any of its agencies or instrumentalities other than Fannie Mae." (Verbiage changed from all-caps to standard case for readability).[67]

However, the implied guarantee, as well as various special treatments given to Fannie by the government, greatly enhanced its success.

For example, the implied guarantee allowed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to save billions in borrowing costs, as their credit rating was very good. Estimates by the Congressional Budget Office and the Treasury Department put the figure at about $2 billion per year.[68] Vernon L. Smith, recipient of the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences, has called FHLMC and FNMA "implicitly taxpayer-backed agencies".[69] The Economist has referred to "the implicit government guarantee"[70] of FHLMC and FNMA. In testimony before the House and Senate Banking Committee in 2004, Alan Greenspan expressed the belief that Fannie Mae's (weak) financial position was the result of markets believing that the U.S. Government would never allow Fannie Mae (or Freddie Mac) to fail.[71]

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were allowed to hold less capital than normal financial institutions: e.g., they were allowed to sell mortgage-backed securities with only half as much capital backing them up as would be required of other financial institutions. Regulations exist through the FDIC Bank Holding Company Act that govern the solvency of financial institutions. The regulations require normal financial institutions to maintain a capital/asset ratio greater than or equal to 3%.[72] The GSEs, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, are exempt from this capital/asset ratio requirement and can, and often do, maintain a capital/asset ratio less than 3%. The additional leverage allows for greater returns in good times, but put the companies at greater risk in bad times, such as during the subprime mortgage crisis. FNMA is exempt from state and local taxes, except for certain taxes on real estate.[73] In addition, FNMA and FHLMC are exempt from SEC filing requirements; they file SEC 10-K and 10-Q reports, but many other reports, such as certain reports regarding their REMIC mortgage securities, are not filed.

Lastly, money market funds have diversification requirements, so that not more than 5% of assets may be from the same issuer. That is, a worst-case default would drop a fund not more than five percent. However, these rules do not apply to Fannie and Freddie. It would not be unusual to find a fund that had the vast majority of its assets in Fannie and Freddie debt.

In 1996, the Congressional Budget Office wrote "there have been no federal appropriations for cash payments or guarantee subsidies. But in the place of federal funds the government provides considerable unpriced benefits to the enterprises... Government-sponsored enterprises are costly to the government and taxpayers... the benefit is currently worth $6.5 billion annually.".[74]

Accounting

FNMA is a financial corporation which uses derivatives to "hedge" its cash flow. Derivative products it uses include interest rate swaps and options to enter interest rate swaps ("pay-fixed swaps", "receive-fixed swaps", "basis swaps", "interest rate caps and swaptions", "forward starting swaps"). Duration gap is a financial and accounting term for the difference between the duration of assets and liabilities, and is typically used by banks, pension funds, or other financial institutions to measure their risk due to changes in the interest rate. "The company said that in April its average duration gap widened to plus 3 months in April from zero in March." "The Washington-based company aims to keep its duration gap between minus 6 months to plus 6 months. From September 2003 to March, the gap has run between plus to minus one month."

Controversies

Accounting controversy

In late 2004, Fannie Mae was under investigation for its accounting practices. The Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight released a report[75] on September 20, 2004, alleging widespread accounting errors.

Fannie Mae was expected to spend more than $1 billion in 2006 alone to complete its internal audit and bring it closer to compliance. The necessary restatement was expected to cost $10.8 billion, but was completed at a total cost of $6.3 billion in restated earnings as listed in Fannie Mae's Annual Report on Form 10-K.[76]

Concerns with business and accounting practices at Fannie Mae predate the scandal itself. On June 15, 2000, the House Banking Subcommittee On Capital Markets, Securities And Government-Sponsored Enterprises held hearings on Fannie Mae.[77]

On December 18, 2006, U.S. regulators filed 101 civil charges against chief executive Franklin Raines; chief financial officer J. Timothy Howard; and the former controller Leanne G. Spencer. The three were accused of manipulating Fannie Mae earnings to maximize their bonuses. The lawsuit sought to recoup more than $115 million in bonus payments, collectively accrued by the trio from 1998 to 2004, and about $100 million in penalties for their involvement in the accounting scandal. After 8 years of litigation, in 2012, a summary judgment was issued clearing the trio, indicating the government had insufficient evidence that would enable any jury to find the defendants guilty.[78]

Conflict of interest

In June 2008, The Wall Street Journal reported that two former CEOs of Fannie Mae, James A. Johnson and Franklin Raines, had received loans below market rate from Countrywide Financial. Fannie Mae was the biggest buyer of Countrywide's mortgages.[79] The "Friends of Angelo" VIP Countrywide loan program included many people from Fannie Mae; lawyers, executives, etc.[80]

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have given contributions to lawmakers currently sitting on committees that primarily regulate their industry: The House Financial Services Committee; the Senate Banking, Housing & Urban Affairs Committee; or the Senate Finance Committee. The others have seats on the powerful Appropriations or Ways & Means committees, are members of the congressional leadership or have run for president.

2011 SEC charges

In December 2011, six Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac executives, including Daniel Mudd, were charged by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission with securities fraud.[81] "The SEC alleges they 'knew and approved of' misleading statements claiming the companies had minimal exposure to subprime loans at the height of home mortgage bubble."[82] Former Freddie chief financial officer Anthony “Buddy” Piszel, who in February 2011, was CFO of CoreLogic, "had received a notice from the SEC that the agency was considering taking action against him". He then resigned from CoreLogic. Piszel was not among the executives charged in December 2011.[83] Piszel had been succeeded at Freddie by David Kellermann. Kellermann committed suicide during his tenure at Freddie.

A contemporaneous report on the SEC charges continued:

The SEC said Mudd’s misconduct included knowingly giving false testimony to Congress.

Mudd said last week that the government approved Fannie Mae’s disclosures during his tenure.

“Now it appears that the government has negotiated a deal to hold the government, and government-appointed executives who have signed the same disclosures since my departure, blameless – so that it can sue individuals it fired years ago,” he said in a statement last week.[83]

2011 lawsuits

In 2011, the agency had a number of other big banks in the crosshairs as well. JPMorgan (JPM) was one of 18 financial institutions the FHFA sued back in 2011, accusing them of selling to Fannie and Freddie securities that "had different and more risky characteristics than the descriptions contained in the marketing and sales materials". Fannie and Freddie, the government-backed housing finance firms, sustained massive losses on mortgage-backed securities as the housing market imploded, requiring a bailout of over $187 billion. The firms have been controlled by the FHFA since their 2008 rescue. Swiss lender UBS has already reached an $885 million settlement with the FHFA in connection with losses Fannie and Freddie sustained on over $6.4 billion worth of mortgage securities. The agency also settled for undisclosed sums earlier this year with Citigroup (C) and General Electric (GE). The FHFA is reportedly seeking $4 billion from JPMorgan to resolve its claims over $33 billion worth of securities sold to Fannie and Freddie by JPMorgan, Bear Stearns and WaMu. Bank of America (BAC), which acquired Countrywide and Merrill Lynch during the crisis era, could be on the hook for even more. The Charlotte-based firm is facing claims from the FHFA over $57 billion worth of mortgage bonds. In all, the 18 FHFA lawsuits cover more than $200 billion in allegedly misrepresented securities. The question of whether any individual bankers will be held to account is another matter. Thus far, criminal cases related to the packaging and sale of mortgage-backed securities have been conspicuously absent. The proposed JPMorgan settlement covers only civil charges, and would not settle the question of whether any individual executives engaged in wrongdoing. There is an ongoing federal criminal probe based in Sacramento, Calif., the state where Washington Mutual was based. JPMorgan originally sought to be protected from any criminal charges as part of this deal, but that request was rejected by the government.[84]

2013 allegations of kickbacks

On May 29, 2013 the Los Angeles Times reported that a former foreclosure specialist at Fannie Mae has been charged but pleaded “not guilty" to accepting a kickback from an Arizona real estate broker in a Santa Ana Federal court. Another lawsuit filed earlier in Orange County Superior Court, this one for wrongful termination, has been filed against Fannie Mae by an employee who claims she was fired when she tried to alert management to kickbacks. The employee claims that she started voicing her suspicions in 2009.[85]

Related legislation

On May 8, 2013, Representative Scott Garrett introduced the Budget and Accounting Transparency Act of 2014 (H.R. 1872; 113th Congress) into the United States House of Representatives during the 113th United States Congress. The bill, if it were passed, would modify the budgetary treatment of federal credit programs, such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.[86] The bill would require that the cost of direct loans or loan guarantees be recognized in the federal budget on a fair-value basis using guidelines set forth by the Financial Accounting Standards Board.[86] The changes made by the bill would mean that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were counted on the budget instead of considered separately and would mean that the debt of those two programs would be included in the national debt.[87] These programs themselves would not be changed, but how they are accounted for in the United States federal budget would be. The goal of the bill is to improve the accuracy of how some programs are accounted for in the federal budget.[88]

2015 ruling

On May 11, 2015 The Wall Street Journal reported that A U.S. District Court judge said Nomura Holdings Inc. was not truthful in describing mortgage-backed securities sold to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, giving a victory to the companies’ conservator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA). Judge Denise Cote asked the FHFA to propose updated damages to be paid by Nomura and co-defendant RBS Securities Inc., which underwrote some of the investments. At the outset of the case, the FHFA asked for about $1.1 billion. The order brought to conclusion a rare trial addressing alleged mortgage-related infractions committed during the housing boom. Over the past few years, more than a dozen firms chose to settle similar allegations brought by the FHFA rather than face a court battle. The settlements have brought Fannie and Freddie $18 billion in penalties. In her decision, Judge Cote wrote that Nomura, in offering documents for mortgage-backed securities sold to Fannie and Freddie, didn't accurately describe the loans’ quality. “The magnitude of falsity, conservatively measured, is enormous,” she wrote. During the boom, Fannie and Freddie invested billions of dollars in mortgage-backed securities issued by such companies as Nomura. Those investments bolstered profits but, in the bust, contributed to steep losses that ultimately resulted in the companies’ 2008 government takeover. Nomura and RBS were two of 18 financial institutions, including Bank of America Corp. and Goldman Sachs Group Inc., targeted in 2011 by the FHFA, which alleged that the companies lied about the quality of the loans underlying the securities. During the nonjury trial, lawyers for the FHFA said that Nomura and RBS inflated values of homes behind some mortgages and sometimes said a home was owner-occupied when it was not.[89]

Leadership

Chief executive officer

- Hugh R. Frater (Oct 16, 2018–)

- Timothy Mayopoulos (2012–2018)

- Michael Williams (2009–2012 )

- Herbert M. Allison (2008–2009)

- Daniel Mudd (2005–2008)

- Franklin Raines (1999–2004)[90]

- James A. Johnson (1991–1998)

- David O. Maxwell (1981[91]-1991)

- Allan O. Hunter (1970–1981)[92]

Key people

- Board of Directors 2018

- Renee Lewis Glover, Age 69, Independent director since January 2016

- Michael J. Heid, Age 61, Independent director since May 2016

- Robert H. Herz, Age 65, Independent director since June 2011

- Antony Jenkins, Age 57, Independent director since July 2018

- Diane C. Nordin, Age 60, Independent director since November 2013

- Jonathan Plutzik, Age 64, Board chair since December 2018, Independent director since November 2009

- Manuel “Manolo” Sánchez Rodríguez, Age 53, Independent director since September 2018

- Ryan A. Zanin, Age 56, independent director since September 2016

- Executive Officers, As of February 14, 2019, there are seven other executive officers:

- David C. Benson, Age 59 President

- Andrew J. Bon Salle, Age 53 Executive Vice President—Single-Family Mortgage Business

- Celeste M. Brown, Age 42 Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer

- John S. Forlines, Age 55 Senior Vice President and Chief Risk Officer

- Jeffery R. Hayward, Age 62 Executive Vice President and Head of Multifamily

- Kimberly H. Johnson, Age 46 Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer

- Stephen H. McElhennon, Age 49 Senior Vice President and Interim General Counsel

- Named Executives for 2018

- Hugh R. Frater Interim Chief Executive Officer (beginning October 2018)

- Timothy J. Mayopoulos Former Chief Executive Officer (until October 2018)

- Celeste M. Brown Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer (beginning August 2018)

- David C. Benson President (beginning August 2018) Former Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer (until August 2018)

- Andrew J. Bon Salle Executive Vice President—Single-Family Mortgage Business

- Jeffery R. Hayward Executive Vice President and Head of Multifamily

- Kimberly H. Johnson Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer (beginning March 2018) Former Executive Vice President and Chief Risk Officer (until March 2018)

See also

References

- https://www.fanniemae.com/newsroom/fannie-mae-news/fannie-mae-names-sheila-c-bair-new-chair-board-directors

- Pickert, Kate (July 14, 2008). "A Brief History of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac". Time.

- "About Fannie Mae". Fendral National Mortgage Association. October 7, 2008. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008. Retrieved October 28, 2008.

- Fabozzi, Frank J.; Modigliani, Franco (1992), Mortgage and Mortgage-backed Securities Markets, Harvard Business School Press, p. 2, ISBN 0-87584-322-0

- "Fortune 500 Companies 2018: Who Made the List". Fortune. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- "The history of Fannie mae - About us - History". www.fanniemae.com. Fannie mae - official website. Archived from the original on November 5, 2017. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- "A Brief History of the Housing Government Sponsored Enterprises" (PDF).

- "2006 Annual Report" (PDF). Fanniemae.com. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Alford, Rob. "History News Network | What Are the Origins of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae?". Hnn.us. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Fabozzi, Frank J.; Modigliani, Franco (1992), Mortgage and Mortgage-backed Securities Markets, Harvard Business School Press, pp. 19–20, ISBN 0-87584-322-0

- McLean, Bethany (September 14, 2015). Shaky Ground: The Strange Saga of the U.S. Mortgage Giants. Columbia Global Reports. ISBN 9780990976301.

- "General Records of the Department of Housing and Urban Development". National Archives and Records Administration.

- "12 U.S. Code Chapter 13, Subchapter III - NATIONAL MORTGAGE ASSOCIATIONS | LII / Legal Information Institute". Law.cornell.edu. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Krishna Guha, Saskia Scholtes, James Politi: Saviours of the suburbs, Financial Times, June 4, 2008, page 13

- Fabozzi, Frank J.; Modigliani, Franco (1992), Mortgage and Mortgage-backed Securities Markets, Harvard Business School Press, p. 20, ISBN 0-87584-322-0

- J. Keith Baker (2010). Residential Mortgage Loan Origination 2nd edition. p. 8.

- Fabozzi, Frank J.; Modigliani, Franco (1992), Mortgage and Mortgage-backed Securities Markets, Harvard Business School Press, p. 21, ISBN 0-87584-322-0

- "George Bush: Statement on Signing the Housing and Community Development Act of 1992". Presidency.ucsb.edu. October 28, 1992. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- "12 U.S. Code § 4501 - Congressional findings | LII / Legal Information Institute". Law.cornell.edu. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- "12 U.S. Code § 4562 - Single-family housing goals | LII / Legal Information Institute". Law.cornell.edu. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Holmes, Steven A. (September 30, 1999). "Fannie Mae Eases Credit To Aid Mortgage Lending". The New York Times.

- Holmes, Steven A. (September 30, 1999). "Fannie Mae Eases Credit To Aid Mortgage Lending". The New York Times. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- "Key Figures in the Financial Crisis: Franklin Raines and Daniel Mudd - BusinessWeek". Images.businessweek.com. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Leonnig, Carol D. (June 10, 2008). "How HUD Mortgage Policy Fed The Crisis". Washington Post.

- Mudd, Daniel (April 17, 2007). "Opening Statement as Submitted to the U.S. House Committee on Financial Services". Fannie Mae. Archived from the original on September 9, 2008.

- Berenson, Alex (August 7, 2003). "Fannie Mae's Loss Risk Is Larger, Computer Models Show". The New York Times.

- "The Black Swan: Quotes & Warnings that the Imbeciles Chose to Ignore". Fooledbyrandomness.com. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- http://www.govtrack.us/congress/record.xpd?id=109-s20050126-53&bill=s109-190#sMonofilemx003Ammx002Fmmx002Fmmx002Fmhomemx002Fmgovtrackmx002Fmdatamx002Fmusmx002Fm109mx002Fmcrmx002Fms20050126-53.xmlElementm39m0m0m. Retrieved October 15, 2008. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "S. 190: Federal Housing Enterprise Regulatory Reform Act of 2005". 109th Congress. GovTrack.us. July 28, 2005. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- "S. 190 Cosponsor Record". Congressional Record – 109th Congress. Library of Congress. May 25, 2006. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- Archived October 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Statement of Administration Policy" (PDF). Georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- "H.R. 1461: Federal Housing Finance Reform Act of 2005". 109th Congress. GovTrack.us. October 31, 2005. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- HUD 2002 Annual Housing Activities Report

- "Explaining the Housing Bubble by Adam J. Levitin, Susan M. Wachter" (PDF). SSRN. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1669401. S2CID 14497941. SSRN 1669401. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Davidson, Paul (October 22, 2010). "Fannie, Freddie bailout to cost taxpayers $154 billion". USA Today.

- Duhigg, Charles (July 11, 2008). "Loan-Agency Woes Swell From a Trickle to a Torrent". The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Grynbaum, Michael M. (July 12, 2008). "Woes at Loan Agencies and Oil-Price Spike Roil Markets". The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Politi, James (July 12, 2008). "Paulson stands by Fannie and Freddie". FT.com. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- On the Brink, Henry Paulson

- On the Brink, Henry Paulson

- Schwartz, Nelson D.; Roose, Kevin (September 2, 2011). "Bank Suits Over Mortgages are Filed". The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Lockhart, James B., III (September 7, 2008). "Statement of FHFA Director James B. Lockhart". Federal Housing Finance Agency. Archived from the original on September 12, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- "Fact Sheet: Questions and Answers on Conservatorship" (PDF). Federal Housing Finance Agency. September 7, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 9, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Goldfarb, Zachary A.; David Cho; Binyamin Appelbaum (September 7, 2008). "Treasury to Rescue Fannie and Freddie: Regulators Seek to Keep Firms' Troubles From Setting Off Wave of Bank Failures". Washington Post. pp. A01. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Hilzenrath, David S.; Zachary A. Goldfarb (September 5, 2008). "Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac to be Put Under Federal Control, Sources Say". Washington Post. Retrieved September 5, 2008.

- Labaton, Stephen; Andres Ross Sorkin (September 5, 2008). "U.S. Rescue Seen at Hand for 2 Mortgage Giants". The New York Times. Retrieved September 5, 2008.

- Hilzenrath, David S.; Neil Irwin; Zachary A. Goldfarb (September 6, 2008). "U.S. Nears Rescue Plan For Fannie And Freddie Deal Said to Involve Change of Leadership, Infusions of Capital". Washington Post. pp. A1. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- Paulson, Henry M. Jr. (September 7, 2008). "Statement by Secretary Henry M. Paulson, Jr. on Treasury and Federal Housing Finance Agency Action to Protect Financial Markets and Taxpayers" (Press release). United States Department of the Treasury. Archived from the original on September 9, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Herszenhorn, David (July 27, 2008). "Congress Sends Housing Relief Bill to President". The New York Times. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- Herszenhorn, David M. (July 31, 2008). "Bush Signs Sweeping Housing Bill". The New York Times. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

-

See HR 3221, signed into law as Public Law 110-289: A bill to provide needed housing reform and for other purposes.

Access to Legislative History: Library of Congress THOMAS: A bill to provide needed housing reform and for other purposes.

White House pre-signing statement: Statement of Administration Policy: H.R. 3221 – Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 Archived September 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine (July 23, 2008 ). Executive office of the President, Office of Management and Budget, Washington DC. - Adler, Lynn (June 16, 2010). "Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac to delist shares on NYSE". Reuters. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- Levine, Jason (2017-03-2017). "The D.C. Circuit Decision On The "Net Worth Sweep" Was Not A Clean Sweep For The Government - The Federalist Society". fed-soc.org/. Retrieved July 11, 2017. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - bailout scorecard

- Forbes Fannie Mae pays

- "Fannie Mae". Archived from the original on May 8, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- Bloomberg Payment will exceed bailout

- CNN bailout now profitable

- Usa Today bailouts repaid

- All the Devils are Here, Bethany McClean, Joe Nocera, Penguin/Portfolio 2010

- Hilzenrath, David S. (August 18, 2008). "Fannie's Perilous Pursuit of Subprime Loans". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Lemke, Lins and Picard, Mortgage-Backed Securities, Chapters 2 and 4 (Thomson West, 2013 ed.).

- Morgenson, Gretchen; Charles Duhigg (September 6, 2008). "Mortgage Giant Overstated the Size of Its Capital Base". The New York Times. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Krovvidy S. (2008). Custom DU: A Web-Based Business User-Driven Automated Underwriting System. AI Magazine. Free-full text Archived May 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine (abstract ).

- "High-Balance Loans in Fannie Mae MBS" (PDF). Fannie Mae. 2008.

- "FannieMae Single-Family MBS Prospectus" (PDF). January 1, 2006. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- McKinley, Vern (November 17, 1997). "Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae: Corporate Welfare King & Queen | Cato Institute". Cato.org. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Smith, Vernon L. (December 18, 2007). "The Clinton Housing Bubble - WSJ". Online.wsj.com. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- "Business and finance". The Economist. March 6, 2015. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Andrews, Edmund L. (February 25, 2004). "Fed Chief Warns of a Risk to Taxpayers - NYTimes.com". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Capital Adequacy Guidelines for Bank Holding Companies: Tier 1 Leverage Measure, Appendix D to 12 C.F.R. Part 225, FDIC's Law, Regulations & Related Acts Index

- "12 U.S. Code § 1723a - General powers of Government National Mortgage Association and Federal National Mortgage Association". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- "Assessing the Public Costs and Benefits of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac | Congressional Budget Office". Cbo.gov. May 1, 1996. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Archived May 19, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- Archived February 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Archived June 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 26, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Simpson, Glenn R. (June 7, 2008). "Countrywide Friends Got Good Loans - WSJ". Online.wsj.com. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Friends of Angelo program, article

- "SEC Charges Former Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac Executives with Securities Fraud; Release No. 2011-267; December 16, 2011". Sec.gov. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Andrejczak, Matt (December 16, 2011). "SEC charges 6 ex-Fannie, Freddie execs with fraud". MarketWatch. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Hilzenrath, David S. (December 21, 2011). "Daniel Mudd, ex-Fannie Mae CEO, takes leave of absence [sic] from hedge fund firm". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- O'Toole, James (October 23, 2013). "More banks in the crosshairs after JPMorgan deal". CNN.

- Reckard, E. Scott (May 27, 2013). "Kickbacks as 'a natural part of business' at Fannie Mae alleged". Los Angeles Times.

- "H.R. 1872 - CBO" (PDF). United States Congress. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- Kasperowicz, Pete (March 28, 2014). "House to push budget reforms next week". The Hill. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- Kasperowicz, Pete (April 4, 2014). "Next week: Bring out the budget". The Hill. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- Light, Joe (May 11, 2015) The Wall Street Journal https://www.wsj.com/articles/judge-rules-against-nomura-in-fhfa-suit-over-sales-to-fannie-freddie-1431370471

- "Frank Raines - 25 People to Blame for the Financial Crisis". TIME. February 11, 2009. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Collins, Jim (July 21, 2003). "The 10 Greatest CEOs Of All Time What these extraordinary leaders can teach today's troubled executives. - July 21, 2003". Money.cnn.com. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- "Feud over Fannie Mae". TIME. February 27, 1978. Retrieved December 30, 2006.

- [|website=http://www.fanniemae.com/resources/file/ir/pdf/quarterly-annual-results/2018/q42018.pdf "Year-End Results/Annual Report on Form 10-K"] Check

|url=value (help) (PDF). |website=http://www.fanniemae.com/resources/file/ir/pdf/quarterly-annual-results/2018/q42018.pdf. March 17, 2019.

External links

- Official website

- Fannie Mae Profile, BusinessWeek

- Fannie Mae Profile, The New York Times

- Fannie Mae Foundation at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived October 9, 2001)