Alabama Legislature

The Alabama Legislature is the legislative branch of the state government of Alabama. It is a bicameral body composed of the House of Representatives and Senate. It is one of the few state legislatures in which members of both chambers serve four-year terms and in which all are elected in the same cycle. The most recent election was on November 6, 2018. The new legislature assumes office immediately following the certification of the election results by the Alabama Secretary of State which occurs within a few days following the election.

Alabama Legitslature | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Houses | Senate House of Representatives |

Term limits | None |

| History | |

New session started | February 28, 2017 |

| Leadership | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 140 |

.svg.png.webp) | |

Senate political groups |

|

| |

House of Representatives political groups |

|

| Authority | Article IV, Alabama Constitution |

| Salary | $10/day + per diem |

| Elections | |

Senate last election | November 6, 2018 |

House of Representatives last election | November 6, 2018 |

Senate next election | November 8, 2022 |

House of Representatives next election | November 8, 2022 |

| Redistricting | Legislative Control |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Alabama State House Montgomery, Alabama | |

| Website | |

| Alabama Legislature | |

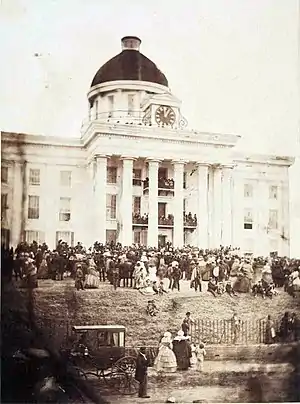

The Legislature meets in the Alabama State House in Montgomery. The original capitol building, located nearby, has not been used by the Legislature on a regular basis since 1985, when it closed for renovations. In the 21st century, it serves as the seat of the executive branch as well as a museum.

History

Establishment

The Alabama Legislature was founded in 1818 as a territorial legislature for the Alabama Territory. Following the federal Alabama Enabling Act of 1819 and the successful passage of the first Alabama Constitution in the same year, the Alabama General Assembly became a fully fledged state legislature upon the territory's admission as a state. The term of state representatives is two years and the term of state senators is four years.

The General Assembly was one of the 11 state legislatures of the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. Following the state's secession from the Union in January 1861, delegates from across the South met at the state capital of Montgomery to create the Confederate government. Between February and May 1861, Montgomery served as the Confederacy's capital, where Alabama state officials let members of the new Southern federal government make use of its offices. The Provisional Confederate Congress met for three months inside the General Assembly's chambers at the Alabama State Capitol. Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as the Confederacy's first and only president on the steps of the capitol.

However, following complaints from Southerners over Montgomery's uncomfortable conditions and, more importantly, following Virginia's entry into the Confederacy, the Confederate government moved to Richmond in May 1861.

Reconstruction era

Following the Confederacy's defeat in 1865, the state government underwent a transformation following emancipation of enslaved African Americans, and constitutional amendments to grant them citizenship and voting rights. Congress dominated the next period of Reconstruction, which some historians attribute to Radical Republicans. For the first time, African-Americans could vote and were elected to the legislature. Republicans were elected to the state governorship and dominated the General Assembly; more than eighty percent of the members were white.

In 1867, a state constitutional convention was called, and a biracial group of delegates worked on a new constitution. The biracial legislature passed a new constitution in 1868, establishing public education for the first time, as well as institutions such as orphanages and hospitals to care for all the citizens of the state. This constitution, which affirmed the franchise for freedmen, enabled Alabama to be readmitted into the United States in 1868.

As in other states during Reconstruction, former Confederate and insurgent "redeemer" forces from the Democratic Party gradually overturned the Republicans by force and fraud. Elections were surrounded by violence as paramilitary groups aligned with the Democrats worked to suppress black Republican voting. By the 1874 state general elections, the General Assembly was dominated by White Americans Bourbon Democrats from the elite planter class.

Both the resulting 1875 and 1901 constitutions disenfranchised African-Americans, and the 1901 also adversely affected thousands of poor White Americans, by erecting barriers to voter registration. Late in the 19th century, a Populist-Republican coalition had gained three congressional seats from Alabama and some influence in the state legislature. After suppressing this movement, Democrats returned to power, gathering support under slogans of white supremacy. They passed a new constitution in 1901 that disenfranchised most African-Americans and tens of thousands of poor White Americans, excluding them from the political system for decades into the late 20th century. The Democratic-dominated legislature passed Jim Crow laws creating legal segregation and second-class status for African-Americans. The 1901 Constitution changed the name of the General Assembly to the Alabama Legislature. (Amendment 427 to the Alabama Constitution designated the State House as the official site of the legislature.)

Civil Rights era

Following World War II, the state capital was a site of important civil rights movement activities. In December 1955 Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat for a white passenger on a segregated city bus. She and other African-American residents conducted the more than year-long Montgomery bus boycott to end discriminatory practices on the buses, 80% of whose passengers were African Americans. Both Parks and Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., a new pastor in the city who led the movement, gained national and international prominence from these events.

Throughout the late 1950s and into the 1960s, the Alabama Legislature and a series of succeeding segregationist governors massively resisted school integration and demands of social justice by civil rights protesters.

During this period, the Legislature passed a law authorizing the Alabama State Sovereignty Commission. Mirroring Mississippi's similarly named authority, the commission used taxpayer dollars to function as a state intelligence agency: it spied on Alabama residents suspected of sympathizing with the civil rights movement (and classified large groups of people, such as teachers, as potential threats). It kept lists of suspected African-American activists and participated in economic boycotts against them, such as getting suspects fired from jobs and evicted from rentals, disrupting their lives and causing financial distress. It also passed on the names of suspected activists to local governments and citizens' groups such as the White Citizens Council, which also followed tactics to penalize activists and enforce segregation.

Following a federal constitutional amendment banning use of poll taxes in federal elections, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 authorizing federal oversight and enforcement of fair registration and elections, and the 1966 US Supreme Court ruling that poll taxes at any level were unconstitutional, African Americans began to register and vote again in numbers proportional to their population. They were elected again to the state legislature and county and city offices for the first time since the late 19th century.

Federal court cases increased political representation for all residents of the state in a different way. Although required by its state constitution to redistrict after each decennial census, the Alabama legislature had not done so from the turn of the century to 1960. In addition, state senators were elected from geographic counties. As a result, representation in the legislature did not reflect the state's changes in population, and was biased toward rural interests. It had not kept up with the development of major urban, industrialized cities such as Birmingham and Tuscaloosa. Their residents paid much more in taxes and revenues to the state government than they received in services. Services and investment to support major cities had lagged due to under-representation in the legislature.

Under the principle of one man, one vote, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Reynolds v. Sims (1964) that both houses of any state legislature need to be based on population, with apportionment of seats redistricted as needed according to the decennial census.[1] This was a challenge brought by citizens of Birmingham. When this ruling was finally implemented in Alabama by court order in 1972, it resulted in the districts including major industrial cities gaining more seats in the legislature.

In May 2007, the Alabama Legislature officially apologized for slavery, making it the fourth Deep South state to do so.

Constitutions

Alabama has had a total of six different state constitutions, passed in 1819, 1861, 1865, 1868, 1875, and 1901. The current constitution (1901) has had so many amendments, most related to decisions on county-level issues, that it is the longest written constitution in both the United States and the world. Because the Alabama legislature has kept control of most counties, authorizing home rule for only a few, it passes numerous laws and amendments that deal only with county-level issues.

Due to the suppression of black voters after Reconstruction, and especially after passage of the 1901 disenfranchising constitution, most African-Americans and tens of thousands of poor White Americans were excluded from voting for decades.[2][3] After Reconstruction ended no African-Americans served in the Alabama Legislature until 1970 when two black majority districts in the House elected Thomas Reed and Fred Gray. As of the 2018 election, the Alabama House of Representatives has 27 African-American members and the Alabama State Senate has 7 African-American members.

Most African-Americans did not regain the power to vote until after passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Before that, many left the state in the Great Migration to northern and midwestern cities. Since the late 20th century, the white majority in the state has voted increasingly Republican. In the 2010 elections, for the first time in 136 years, both houses of the state legislature were dominated by Republicans. Republicans have maintained their majority status in the succeeding elections in 2014 and 2018.

Organization

The Alabama Legislature convenes in regular annual sessions on the first Tuesday in February, except during the first year of the four-year term, when the session begins on the first Tuesday in March. In the last year of a four-year term, the legislative session begins on the second Tuesday in January. The length of the regular session is limited to 30 meeting days within a period of 105 calendar days. Session weeks consist of meetings of the full chamber and committee meetings.

The Governor of Alabama can call, by proclamation, special sessions of the Alabama Legislature and must list the subjects to be considered. Special sessions are limited to 12 legislative days within a 30 calendar day span. In a regular session, bills may be enacted on any subject. In a special session, legislation must be enacted only on those subjects which the governor announces on their proclamation or "call." Anything not in the "call" requires a two-thirds vote of each house to be enacted.

Legislative process

Alabama's lawmaking process differs somewhat from the other 49 states.

Notice and introduction of bills

Prior to the introduction of bills that apply to specific, named localities, the Alabama Constitution requires publication of the proposal in a newspaper in the counties to be affected. The proposal must be published for four consecutive weeks and documentation must be provided to show that the notice was posted. The process is known as "notice and proof."

Article 4, Section 45 of the state constitution mandates that each bill may only pertain to one subject, clearly stated in the bill title, "except general appropriation bills, general revenue bills, and bills adopting a code, digest, or revision of statutes".

Committees

As with other legislative bodies throughout the world, the Alabama legislature operates mainly through committees when considering proposed bills. The Constitution of Alabama states that no bill may be enacted into law until it has been referred to, acted upon by, and returned from, a standing committee in each house. Reference to committee immediately follows the first reading of the bill. Bills are referred to committees by the presiding officer.

The state constitution authorizes each house to determine the number of committees, which varies from quadrennial session to session. Each committee is set up to consider bills relating to a particular subject.

Legislative Council

The Alabama legislature has a Legislative Council, which is a permanent or continuing interim committee, composed as follows:

- From the Senate, the Lieutenant Governor and President Pro-Tempore, the Chairmen of Finance and Taxation, Rules, Judiciary, and Governmental Affairs, and six Senators elected by the Senate;

- From the House of Representatives, the Speaker and Speaker Pro-Tempore, the Chairmen of Ways and Means, Rules, Judiciary, and Local Government, and six Representatives elected by the House.

- The majority and minority leaders of each house.

The Legislative Council meets at least once quarterly to consider problems for which legislation may be needed, and to make recommendations for the next legislative session.

Committee reports

After a committee completes work on a bill, it reports the bill to the appropriate house during the "reports of committees" in the daily order of business. Reported bills are immediately given a second reading. The houses do not vote on a bill at the time it is reported; however, reported bills are placed on the calendar for the next legislative day. The second reading is made by title only. Local bills concerning environmental issues affecting more than one political subdivision of the state are given a second reading when reported from the local legislation committee and re-referred to a standing committee where they are then considered as a general bill. Bills concerning gambling are also re-referred when reported from the local legislation committee but they continue to be treated as local bills. When reported from the second committee, these bills are referred to the calendar and do not require another second reading.

The regular calendar is a list of bills that have been favorably reported from committee and are ready for consideration by the membership of the entire house.

Bills are listed on the calendar by number, sponsor, and title, in the order in which they are reported from committee. They must be considered for a third reading in that order unless action is taken to consider a bill out of order. Important bills are brought to the top of the calendar by special orders or by suspending the rules. To become effective, the resolution setting special orders must be adopted by a majority vote of the house. These special orders are recommended by the Rules Committee of each house. The Rules Committee is not restricted to making its report during the Call of Committees, and can report at any time. This enables the committee to determine the order of business for the house. This power makes the Rules Committee one of the most influential of the legislative committees.

Any bill which affects state funding by more than $1,000, and which involves expenditure or collection of revenue, must have a fiscal note. Fiscal notes are prepared by the Legislative Fiscal Office and signed by the chairman of the committee reporting the bill. They must contain projected increases or decreases to state revenue in the event that the bill becomes law.

Third reading

A bill is placed on the calendar for adoption for its third reading. It is at this third reading of the bill that the whole house gives consideration to its passage. At this time, the bill may be studied in detail, debated, amended, and read at length before final passage.

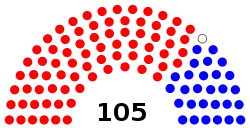

Once the bill is discussed, each member casts his or her vote, and their name is called alphabetically to record their vote. Since the state's Senate has only 35 members, voting may be done effectively in that house by a roll call of the members. The membership of the House is three times larger, with 105 members; since individual roll-call voice votes are time-consuming, an electronic voting machine is used in the House of Representatives. The House members vote by pushing buttons on their desks, and their votes are indicated by colored lights which flash on a board in the front of the chamber. The board lists each member name and shows how each member voted. The votes are electronically recorded in both houses.

If a majority of the members who are present and voting in each house vote against a bill, or if there is a tie vote,[4] it fails passage. If the majority vote in favor of the bill, its approval is recorded as passing. If amendments are adopted, the bill is sent to the Enrolling and Engrossing Department of that house for engrossment. Engrossment is the process of incorporating amendments into the bill before transmittal to the second house.

Transmission to second house

A bill that is passed in one house is transmitted, along with a formal message, to the other house. Such messages are always in order and are read (in the second house) at any suitable pause in business. After the message is read, the bill receives its first reading, by title only, and is referred to committee. In the second house, a bill must pass successfully through the same steps of procedure as in the first house. If the second house passes the bill without amendment, the bill is sent back to the house of origin and is ready for enrollment, which is the preparation of the bill in its final form for transmittal to the governor. However, the second house may amend the bill and pass it as amended. Since a bill must pass both houses in the same form, the bill with amendment is sent back to the house of origin for consideration of the amendment. If the bill is not reported from committee or is not considered by the full house, the bill is defeated.

The house of origin, upon return of its amended bill, may take any one of several courses of action. It may concur in the amendment by the adoption of a motion to that effect; then the bill, having been passed by both houses in identical form, is ready for enrollment. Another possibility is that the house of origin may adopt a motion to non-concur in the amendment, at which point the bill dies. Finally, the house of origin may refuse to accept the amendment but request that a conference committee be appointed. The other house usually agrees to the request, and the presiding officer of each house appoints members to the conference committee.

Conference committees

Conferences committee is empaneled to discusses the points of difference between the two houses' versions of the same bill, and assigned members try to reach an agreement on the content so that the bill can be passed by both houses. If an agreement is reached and if both houses adopt the conference committee's report, the bill is passed. If either house refuses to adopt the report of the conference committee, a motion may be made for further conference. If a conference committee is unable to reach an agreement, it may be discharged, and a new conference committee may be appointed. Highly controversial bills may be referred to several different conference committees. If an agreement is never reached in conference prior to the end of the legislative session, the bill is lost.

When a bill has passed both houses in identical form, it is enrolled. The "enrolled" copy is the official bill, which, after it becomes law, is kept by the Secretary of State for reference in the event of any dispute as to its exact language. Once a bill has been enrolled, it is sent back to the house of origin, where it must be read again (unless this reading is dispensed with by a two-thirds vote), and signed by the presiding officer in the presence of the members. The bill is then sent to the other house where the presiding officer in the presence of all the members of that house also signs it. The bill is then ready for transmittal to the governor.

Presentation to the governor

Once a bill reaches the governor, he or she may sign it, which completes its enactment into law. From this point, the bill becomes an act, and remains the law of the state unless repealed by legislative action, or overturned by a court decision. If the governor does not approve of the bill, he or she may veto it. Vetoed bills return to the house in which they originated, with a message explaining the governor's objections and suggesting amendments that might remove those objections. The bill is then reconsidered, and if a simple majority of the members of both houses agrees to the proposed executive amendments, it is returned to the governor, as he revised it, for his signature. The governor is also permitted the line-item veto on appropriations bills.

In contrast to the practice of most states and the federal government (which require a supermajority, usually 2/3, to override a veto), a simple majority of the members of each house can choose to approve a vetoed bill precisely as the Legislature originally passed it, in which case it becomes a law over the governor's veto.

If the governor fails to return a bill to the legislative house in which it originated within six days after it was presented to him or her (including Sundays), it becomes a law without their signature. This return can be prevented by recession of the Legislature. In that case the bill must be returned within two days after the legislature reassembles, or it becomes a law without the governor's signature.

The bills that reach the governor less than five days before the end of the session may be approved within ten days after adjournment. The bills not approved within that time do not become law. This is known as a "pocket veto". This is the most conclusive form of veto, since state lawmakers have no chance to reconsider the vetoed measure.

Constitutional amendments

Legislation that would change the state constitution takes the form of a constitutional amendment. A constitutional amendment is introduced and takes the same course as a bills or resolution, except it must be read at length on three different days in each house, must pass each house by a three-fifths vote of the membership, and it does not require the approval of the governor. A constitutional amendment passed by the legislature is deposited directly with the Alabama Secretary of State. It is then submitted to voters at an election held not less than three months after the adjournment of the session in which state lawmakers proposed the amendment. The governor announces the election by proclamation, and the proposed amendment and notice of the election must be published in every county for four successive weeks before the election. If a majority of those who vote at the election favor the amendment, it becomes a part of the Alabama Constitution. The result of the election is announced by proclamation of the governor.

Notable members

- Spencer Bachus, U. S. Representative (1993–2015), Member of Alabama Senate (1983–1984), Member of Alabama House (1984–1987)

- Robert J. Bentley, Governor of Alabama (2011–2017), Member of Alabama House (2002–2011)

- Albert Brewer, Governor of Alabama (1968–1971), Member of Alabama House (1954–1966) and its Speaker (1963–1966)

- Mo Brooks, U. S. Representative (2011–present), Member of Alabama House (1984–1992)

- Glen Browder, U. S. Representative (1989-1997), Alabama Secretary of State (1987-1989); Member of Alabama House (1983-1986)

- Sonny Callahan, U. S. Representative (1985–2003), Member of Alabama House (1970–1978), Member of Alabama Senate (1978–1982)

- U. W. Clemon, Federal District Judge (1980–2009), Member of Alabama Senate (1974–1980)

- Ben Erdreich, U. S. Representative (1983–1993), Member of Alabama House (1970–1974)

- Euclid T. Rains, Jr., Member of Alabama House (1978–1990), Blind legislator [5]

- Mike Rogers, U. S. Representative (2003–present), Member of Alabama House (1994–2003)

- Benjamin F. Royal, Member of Alabama Senate (1868-1875), Bullock County, served as first African-American State Senator in Alabama history [6]

- Christopher Sheats, U. S. Representative (1873-1875), Member of Alabama House, (1861-1862), Consul to Denmark (1869-1873)

- Richard Shelby, U. S. Senator (1987–present), Member of Alabama Senate (1970–1978)

- George Wallace, Governor of Alabama (1963–1967, 1971–1979, 1983–1987), Member of Alabama House (1946–1953)

- Hattie Hooker Wilkins, Member of Alabama House (1922-1926), Dallas County, first woman in state history to serve in Alabama Legislature[7]

References

- REYNOLDS v. SIMS, 377 U.S. 533 (1964), FindLaw, accessed 12 March 2015

- J. Morgan Kousser.The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974

- Glenn Feldman, The Disfranchisement Myth: Poor Whites and Suffrage Restriction in Alabama, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004, pp. 135–136

- "SECTION 63". Justia Law. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- Alabama House of Representatives website (legislature.state.al.us), Past Legislators Roster (1922-2018)

- Bailey, Neither Carpetbaggers nor Scalawags (1991)

- Dance, Gabby; Alabama Political Reporter, 7/24/2019