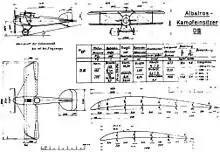

Albatros D.III

The Albatros D.III was a biplane fighter aircraft used by the Imperial German Army Air Service (Luftstreitkräfte) during World War I. A modified licence model was built by Oeffag for the Austro-Hungarian Air Service (Luftfahrtruppen). The D.III was flown by many top German aces, including Wilhelm Frankl, Erich Löwenhardt, Manfred von Richthofen, Karl Emil Schäfer, Ernst Udet, and Kurt Wolff, and Austro-Hungarian ones, like Godwin von Brumowski. It was the preeminent fighter during the period of German aerial dominance known as "Bloody April" 1917.

| D.III | |

|---|---|

| |

| Role | Fighter |

| National origin | German Empire |

| Manufacturer | Albatros-Flugzeugwerke |

| Designer | Robert Thelen |

| First flight | August 1916 |

| Retired | 1923 (Polish Air Force) |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary users | Luftstreitkräfte Austro-Hungarian Air Service |

| Produced | 1916–1918 |

| Number built | 1,866 |

| Developed from | Albatros D.II |

| Developed into | Albatros D.V |

Design and development

Development of the prototype D.III started in late July or early August 1916.[1] The date of the maiden flight is unknown, but is believed to have occurred in late August or early September.[1] Following the successful Albatros D.I and D.II series, the D.III utilized the same semi-monocoque, plywood-skinned fuselage. However, at the request of the Idflieg (Inspectorate of Flying Troops), the D.III adopted a sesquiplane wing arrangement broadly similar to the French Nieuport 11. The upper wingspan was extended, while the lower wing was redesigned with reduced chord and a single main spar. "V" shaped interplane struts replaced the previous parallel struts. For this reason, British aircrews commonly referred to the D.III as the "V-strutter."

After a Typenprüfung (official type test) on 26 September 1916, Albatros received an order for 400 D.III aircraft, the largest German production contract to date.[2] Idflieg placed additional orders for 50 aircraft in February and March 1917.[3]

Operational history

The D.III entered squadron service in December 1916, and was immediately acclaimed by German aircrews for its maneuverability and rate of climb.[3] Two faults with the new aircraft were soon identified. Like the D.II, early D.IIIs featured a Teves und Braun airfoil-shaped radiator in the center of the upper wing, where it tended to scald the pilot if punctured. From the 290th D.III onward, the radiator was offset to the right on production machines while others were soon moved to the right as a field modification. Aircraft deployed in Palestine used two wing radiators, to cope with the warmer climate.

More seriously, the new aircraft immediately began experiencing failures of the lower wing ribs and leading edge,[3] a defect shared with the Nieuport 17. On 23 January 1917, a Jasta 6 pilot suffered a failure of the lower right wing spar.[3] On the following day, Manfred von Richthofen suffered a crack in the lower wing of his new D.III.[3] On 27 January, the Kogenluft (Kommandierender General der Luftstreitkräfte) issued an order grounding all D.IIIs pending resolution of the wing failure problem.[4] On 19 February, after Albatros introduced a reinforced lower wing, the Kogenluft rescinded the grounding order.[5] New production D.IIIs were completed with the strengthened wing while operational D.IIIs were withdrawn to Armee-Flugparks for modifications, forcing Jastas to use the Albatros D.II and Halberstadt D.II during the interim.[6][7]

At the time, the continued wing failures were attributed to poor workmanship and materials at the Johannisthal factory. In fact, the cause of the wing failures lay in the sesquiplane arrangement taken from the Nieuport. While the lower wing had sufficient strength in static tests, it was subsequently determined that the main spar was located too far aft, causing the wing to twist under aerodynamic loads. Pilots were therefore advised not to perform steep or prolonged dives in the D.III. This design flaw persisted despite attempts to rectify the problem in the D.III and succeeding D.V.

Apart from its structural deficiencies, the D.III was considered pleasant and easy to fly, if somewhat heavy on the controls. The sesquiplane arrangement offered improved climb, maneuverability, and downward visibility compared to the preceding D.II. Like most contemporary aircraft, the D.III was prone to spinning, but recovery was straightforward.

Albatros built approximately 500 D.III aircraft at its Johannisthal factory. In the spring of 1917, D.III production shifted to Albatros' subsidiary, Ostdeutsche Albatros Werke (OAW), to permit Albatros to concentrate on development and production of the D.V.[8] Between April and August 1917, Idflieg issued five separate orders for a total of 840 D.IIIs. The OAW variant underwent its Typenprüfung in June 1917.[9] Production commenced at the Schneidemühl factory in June and continued through December 1917. OAW aircraft were distinguishable by their larger, rounded rudders.[10]

Peak service was in November 1917, with 446 aircraft on the Western Front. The D.III did not disappear with the end of production, however. It remained in frontline service well into 1918. As of 31 August 1918, 54 D.III aircraft remained on the Western Front.

Austro-Hungarian variants

_Brumowski.jpg.webp)

_253.01.jpg.webp)

In the autumn of 1916, Oesterreichische Flugzeugfabrik AG (Oeffag) obtained a licence to build the D.III at Wiener-Neustadt. Deliveries commenced in May 1917. The aircraft were officially designated as Albatros D.III (Oeffag), but were known as Oeffag Albatros D.III in Austro-Hungary, and just Oeffag D.III in Poland.[11]

The Oeffag aircraft were built in three main versions (series 53.2, 153, 253) using the 138, 149, or 168 kW (185, 200, or 225 hp) Austro-Daimler engines respectively. The Austro-Daimlers provided improved performance over the Mercedes D.IIIa engine. For cold weather operations, Oeffag aircraft featured a winter cowling which fully enclosed the cylinder heads.

Austrian pilots often removed the propeller spinner from early production aircraft, since it was prone to falling off in flight.[12] Beginning with aircraft 112 of the series 153 production run, Oeffag introduced a new rounded nose that eliminated the spinner. Remarkably, German wind-tunnel tests showed that the simple rounded nose improved propeller efficiency and raised the top speed by 14 km/h (9 mph).[12]

All Oeffag variants were armed with two 8 mm (.315 in) Schwarzlose machine guns. In most aircraft, the guns were buried in the fuselage, where they were inaccessible to the pilot. In service, the Schwarzlose proved to be somewhat less reliable than the 7.92 mm (.312 in) LMG 08/15, mainly due to problems with the synchronization gear.[12] The Schwarzlose also had a poor rate of fire until the 1916 model was provided with a modification developed by Ludwig Kral.[12] At the request of pilots, the guns were relocated to the upper fuselage decking late in the series 253 production run.[12] It helped to warm up the guns on high altitude.[11] This created a new problem; the Schwarzlose operated via blowback and the weapon contained a cartridge oiler to prevent cases from sticking in the chamber while the extractor ripped their rims off. With guns mounted directly in front of the pilot, oil released during firing interfered with aim.

Oeffag engineers noted the wing failures of the D.III and modified the lower wing to use thicker ribs and spar flanges. These changes, as well as other detail improvements, largely resolved the structural problems that had plagued German versions of the D.III.[13] In service, the Oeffag aircraft proved to be popular, robust, and effective. Oeffag built approximately 526 D.III aircraft between May 1917 and the Armistice (586 in total[11] according to other publications).

Postwar

After the Armistice, in early 1919 Poland bought 38 series 253 aircraft from the factory, ten more were rebuilt from wartime leftovers.[11] Poland operated them in the Polish-Soviet War of 1919–20 in two fighter escadrilles (Nos. 7 and 13).[11] Due to rare air encounters, they were primarily employed in ground-attack duties.[11] The Poles thought so highly of the D.III that they sent a letter of commendation to the Oeffag factory. They remained in service until 1923.[11] Poland also had 26 original Albatros D.III, mostly captured from former occupants, but they were withdrawn from use in December 1919 due to structural weaknesses.[14]

The newly formed Czechoslovak Air Force also obtained and operated several Oeffag machines after the war.

Modern reproductions

An Austrian aviation enthusiast, Koloman Mayrhofer, has completed a pair of Albatros D.III (Oeffag) series 253 reproductions. Both are equipped with vintage Austro-Daimler engines. One aircraft will be flown and operated by a non-profit organization. The second aircraft is slated for static display at the Flugmuseum AVIATICUM, near Wiener-Neustadt, Austria.

Operators

- Czechoslovak Air Force - (postwar)

- Lithuanian Air Force - (postwar)

- Polish Air Force (postwar)

- Ottoman Air Force and Turkish Air Force (postwar)

- Yugoslav Royal Air Force (postwar)

Specifications (D.III (Oef) Series 153)

Data from Austro-Hungarian Army Aircraft of World War One[15]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 7.35 m (24 ft 1 in)

- Upper wingspan: 9 m (29 ft 6 in)

- Lower wingspan: 8.73 m (28 ft 8 in)

- Height: 2.8 m (9 ft 2 in)

- Wing area: 20.56 m2 (221.3 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 710 kg (1,565 lb)

- Gross weight: 987 kg (2,176 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Austro-Daimler 200hp 6-cylinder water-cooled in-line piston engine, 150 kW (200 hp)

- Propellers: 2-bladed fixed-pitch wooden propeller

Performance

- Maximum speed: 188 km/h (117 mph, 102 kn)

- Time to altitude:

- 1,000 m (3,281 ft) in 2 minutes 35 seconds

- 2,000 m (6,562 ft) in 6 minutes 35 seconds

- 3,000 m (9,843 ft) in 11 minutes 20 seconds

- 4,000 m (13,123 ft) in 18 minutes 50 seconds

- 5,000 m (16,404 ft) in 33 minutes

- Wing loading: 48.1 kg/m2 (9.9 lb/sq ft)

- Power/mass: 0.20 kg/hp

Armament

- Guns: 2 × 8 mm (0.315 in) Schwarzlose machine guns

References

Notes

- Grosz 2003, p. 6.

- Grosz 2003, p. 8.

- VanWyngarden 2007, p. 19.

- Grosz 2003, p. 11.

- Grosz 2003, p. 13.

- Grosz 2003, pp. 11, 13.

- Franks, Giblin, McCrery 1998, p. 59.

- Grosz 2003, p. 18.

- Grosz 2003, p. 19.

- Grosz 2003, pp. 21–22.

- Morgała (1997), p.154-156

- Grosz, Haddow, Schiemer 2002, p. 251.

- Grosz, Haddow, Schiemer 2002, p. 249.

- Morgała (1997), p.125-126

- Grosz, Peter M.; Haddow, George; Scheiner, Peter (2002) [1993]. Austro-Hungarian Army Aircraft of World War One. Boulder: Flying Machine Press. pp. 248–259. ISBN 1 891268 05 8.

Bibliography

- Connors, John F. Albatros Fighters In Action (Aircraft No. 46). Carrollton, TX: Squadron/Signal Publications, Inc., 1981. ISBN 0-89747-115-6.

- Franks, Norman, Hal Giblin and Nigel McCrery. Under the Guns of the Red Baron: Complete Record of Von Richthofen's Victories and Victims. London: Grub Street, 1998. ISBN 1-84067-145-9.

- Grosz, Peter M. Albatros D.III (Windsock Datafile Special). Berkhamsted, Herts, UK: Albatros Publications, 2003. ISBN 1-902207-62-9.

- Grosz, Peter M. (1984). "Talkback". Air Enthusiast. No. 25. p. 79. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Grosz, Peter M., George Haddow and Peter Schiemer. Austro-Hungarian Army Aircraft of World War I. Boulder, CO: Flying Machines Press, 2002. ISBN 1-891268-05-8.

- Mikesh, Robert C. Albatros D.Va: German Fighter of World War I. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1980. ISBN 0-87474-633-7

- Miller, James F. Albatros D.III: Johannisthal, OAW, and Oeffag Variants (Air Vanguard 13). Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2014. ISBN 978-1-78200-371-7

- Neulen, Hans-Werner & Cony, Christophe (August 2000). "Les aigles du Kaiser en Terre Sainte" [The Kaiser's Eagles in the Holy Land]. Avions: Toute l'Aéronautique et son histoire (in French) (89): 34–43. ISSN 1243-8650.

- VanWyngarden, Greg. Albatros Aces of World War I Part 2 (Aircraft of the Aces No. 77). Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2007. ISBN 1-84603-179-6.

- Morgała, Andrzej (1997). Samoloty wojskowe w Polsce 1918-1924 [Military aircraft in Poland 1918-1924] (in Polish). Warsaw: Lampart. ISBN 83-86776-34-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Albatros D.III. |