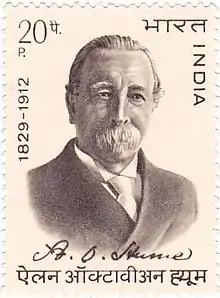

Allan Octavian Hume

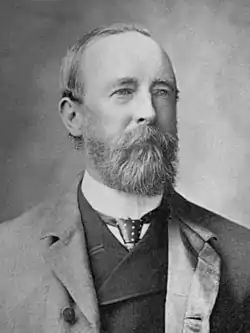

Allan Octavian Hume, CB ICS (4 June 1829[1] – 31 July 1912[2]) was a British member of the Imperial Civil Service (later the Indian Civil Service), a political reformer, ornithologist and botanist who worked in British India. He was one of the founders of the Indian National Congress. A notable ornithologist, Hume has been called "the Father of Indian Ornithology" and, by those who found him dogmatic, "the Pope of Indian ornithology".[3]

Allan Octavian Hume | |

|---|---|

Allan Octavian Hume (1829–1912) (scanned from a Woodburytype) | |

| Born | 4 June 1829 |

| Died | 31 July 1912 (aged 83) |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University College Hospital East India Company College |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Founder of Indian National Congress Father of Indian Ornithology |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Anne Grindall (m. 1853) |

| Children | Maria Jane "Minnie" Burnley |

| Parent(s) | Joseph Hume (father) Maria Burnley (mother) |

| Signature | |

As an administrator of Etawah, he saw the Indian Rebellion of 1857 as a result of misgovernance and made great efforts to improve the lives of the common people. The district of Etawah was among the first to be returned to normality and over the next few years Hume's reforms led to the district being considered a model of development. Hume rose in the ranks of the Indian Civil Service but like his father Joseph Hume, a radical member of parliament, he was bold and outspoken in questioning British policies in India. He rose in 1871 to the position of secretary to the Department of Revenue, Agriculture, and Commerce under Lord Mayo. His criticism of Lord Lytton however led to his removal from the Secretariat in 1879.

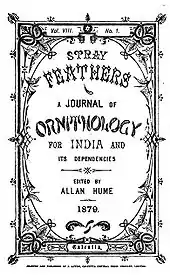

He founded the journal Stray Feathers in which he and his subscribers recorded notes on birds from across India. He built up a vast collection of bird specimens at his home in Shimla by making collection expeditions and obtaining specimens through his network of correspondents.

Following the loss of manuscripts that he had long been maintaining in the hope of producing a magnum opus on the birds of India, he abandoned ornithology and gifted his collection to the Natural History Museum in London, where it continues to be the single largest collection of Indian bird skins. He was briefly a follower of the theosophical movement founded by Madame Blavatsky. He left India in 1894 to live in London from where he continued to take an interest in the Indian National Congress, apart from taking an interest in botany and founding the South London Botanical Institute towards the end of his life.

Life and career

Early life

Hume was born at St Mary Cray, Kent,[4] a younger son (and the eighth child in a family of nine)[5] of Joseph Hume, the Radical member of parliament, by his marriage to Maria Burnley.[2] Until the age of eleven he was privately tutored growing up at the town house at 6 Bryanston Square in London and at their country estate, Burnley Hall in Norfolk.[1] He was educated at University College Hospital,[6] where he studied medicine and surgery and was then nominated to the Indian Civil Services which led him to study at the East India Company College, Haileybury. Early influences included his friend John Stuart Mill and Herbert Spencer.[2] He briefly served as a junior midshipman aboard a navy vessel in the Mediterranean in 1842.[1]

Etawah (1849–1867)

Hume sailed to India in 1849 and the following year, joined the Bengal Civil Service at Etawah in the North-Western Provinces, in what is now Uttar Pradesh. His career in India included service as a district officer from 1849 to 1867, head of a central department from 1867 to 1870, and secretary to the Government from 1870 to 1879.[7] He married Mary Anne Grindall (26 May 1824, Meerut – March 1890, Simla) in 1853.[8]

It was only nine years after his entry to India that Hume faced the Indian Rebellion of 1857 during which time he was involved in several military actions[9][10] for which he was created a Companion of the Bath in 1860. Initially it appeared that he was safe in Etawah, not far from Meerut where the rebellion began but this changed and Hume had to take refuge in Agra fort for six months.[11] Nonetheless, all but one Indian official remained loyal and Hume resumed his position in Etawah in January 1858. He built up an irregular force of 650 loyal Indian troops and took part in engagements with them. Hume blamed British ineptitude for the uprising and pursued a policy of "mercy and forbearance".[2] Only seven persons were executed at the gallows on his orders.[12] The district of Etawah was restored to peace and order in a year, something that was not possible in most other parts.[13]

Shortly after 1857, he set about in a range of reforms. As a District Officer in the Indian Civil Service, he began introducing free primary education and held public meetings for their support. He made changes in the functioning of the police department and the separation of the judicial role. Noting that there was very little reading material with educational content, he started, along with Koour Lutchman Singh, a Hindi language periodical, Lokmitra (The People's Friend) in 1859. Originally meant only for Etawah, its fame spread.[14] Hume also organized and managed an Urdu journal Muhib-i-riaya.[15]

The system of departmental examinations introduced soon after (Hume joined the civil services) enabled Hume so to outdistance his seniors that when the rebellion broke out he was officiating Collector of Etawah, which lies between Agra and Cawnpur. Rebel troops were constantly passing through the district, and for a time it was necessary to abandon headquarters ; but both before and after the removal of the women and children to Agra, Hume acted with vigour and judgment. The steadfast loyalty of many native officials and landowners, and the people generally, was largely due to his influence, and enabled him to raise a local brigade of horse. In a daring attack on a body of rebels at Jaswantnagar he carried away the wounded joint magistrate, Mr. Clearmont Daniel,[16] under a heavy fire, and many months later he engaged in a desperate action against Firoz Shah and his Oudh freebooters at Hurchandpur. Company rule had come to an end before the ravines of the Jumna and the Chambul in the district had been cleared of fugitive rebels. Hume richly merited the C.B. (Civil division) awarded him in 1860. He remained in charge of the district for ten years or so and did good work.

— Obituary The Times of August 1st, 1912

He took up the cause of education and founded scholarships for higher education. He wrote, in 1859, that education played a key role in avoiding revolts like the one in 1857:

... assert its supremacy as it may at the bayonet's point, a free and civilized government must look for its stability and permanence to the enlightenment of the people and their moral and intellectual capacity to appreciate its blessings.[8]

In 1863 he moved for separate schools for juvenile delinquents rather than flogging and imprisonment which he saw as producing hardened criminals. His efforts led to a juvenile reformatory not far from Etawah. He also started free schools in Etawah and by 1857 he established 181 schools with 5186 students including two girls.[17] The high school that he helped build with his own money is still in operation, now as a junior college, and it was said to have a floor plan resembling the letter "H". This, according to some was an indication of Hume's imperial ego.[18] Hume found the idea of earning revenue earned through liquor traffic repulsive and described it as "The wages of sin". With his progressive ideas on social reform, he advocated women's education, was against infanticide and enforced widowhood. Hume laid out in Etawah, a neatly gridded commercial district that is now known as Humeganj but often pronounced Homeganj.[8]

Commissioner of Customs (1867–1870)

In 1867 Hume became Commissioner of Customs for the North West Province, and in 1870 he became attached to the central government as Director-General of Agriculture. In 1879 he returned to provincial government at Allahabad.[8][13]

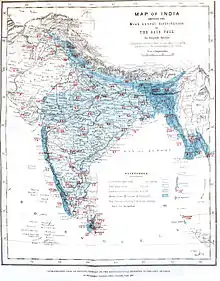

Hume's appointment, in 1867, to be Commissioner of Customs in Upper India gave him charge of the huge physical barrier[19] which stretched across the country for 2,500 miles from Attock, on the Indus, to the confines of the Madras Presidency. He carried out the first negotiations with Rajputana Chiefs, leading to the abolition of this barrier, and Lord Mayo rewarded him with the Secretaryship to Government in the Home, and afterwards, from 1871, in the Revenue and Agricultural Departments.[20]

Secretary to the Department of Revenue, Agriculture and Commerce (1871–1879)

Hume was very interested in the development of agriculture. He believed that there was too much focus on obtaining revenue and no effort had been spent on improving the efficiency of agriculture. He found an ally in Lord Mayo who supported the idea of developing a complete department of agriculture. Hume noted in his Agricultural reform in India that Lord Mayo had been the only Viceroy who had any experience of working in the fields.

Hume made a number of suggestions for the improvement of agriculture placing carefully gathered evidence for his ideas. He noted the poor yields of wheat, comparing them with estimates from the records of Emperor Akbar and yields of farms in Norfolk. Lord Mayo supported his ideas but was unable to establish a dedicated agricultural bureau as the scheme did not find support from the Secretary of State for India, but they negotiated the setting up of a Department of Revenue, Agriculture and Commerce despite Hume's insistence that Agriculture be the first and foremost aim. Hume was made a secretary of this department in July 1871 leading to his move to Shimla.[8]

With the murder of Lord Mayo in the Andamans in 1872, Hume lost patronage and support for his work. He however went about reforming the department of agriculture, streamlining the collection of meteorological data (the meteorological department was set up by order number 56 on 27 September 1875 signed by Hume[21]) and statistics on cultivation and yield.[22]

Hume proposed the idea of having experimental farms to demonstrate best practices to be set up in every district. He proposed to develop fuelwood plantations "in every village in the drier portions of the country" and thereby provide a substitute heating and cooking fuel so that manure (dried cattle dung was used as fuel by the poor) could be returned to the land. Such plantations, he wrote, were "a thing that is entirely in accord with the traditions of the country – a thing that the people would understand, appreciate, and, with a little judicious pressure, cooperate in." He wanted model farms to be established in every district. He noted that rural indebtedness was caused mainly by the use of land as security, a practice that had been introduced by the British. Hume denounced it as another of "the cruel blunders into which our narrow-minded, though wholly benevolent, desire to reproduce England in India has led us." Hume also wanted government-run banks, at least until cooperative banks could be established.[8][23]

The department also supported the publication of several manuals on aspects of cultivation, a list of which Hume included as an appendix to his Agricultural Reform in India. Hume supported the introduction of cinchona and the project managed by George King to produce quinine locally at low cost.[24]

Hume was very outspoken and never feared to criticise when he thought the Government was in the wrong. Even in 1861, he objected to the concentration of police and judicial functions in the hands of police superintendents. In March 1861, he took a medical leave due to a breakdown from overwork and departed for Britain. Before leaving, he condemned the flogging and punitive measures initiated by the provincial government as 'barbarous ... torture'. He was allowed to return to Etawah only after apologising for the tone of his criticism.[2] He criticised the administration of Lord Lytton before 1879 which according to him, had cared little for the welfare and aspiration of the people of India.

Lord Lytton's foreign policy according to Hume had led to the waste of "millions and millions of Indian money".[8] Hume was critical of the land revenue policy and suggested that it was the cause of poverty in India. His superiors were irritated and attempted to restrict his powers and this led him to publish a book on Agricultural Reform in India in 1879.[2][25]

Hume noted that the free and honest expression was not only permitted but encouraged under Lord Mayo and that this freedom was curtailed under Lord Northbrook who succeeded Lord Mayo. When Lord Lytton succeeded Lord Northbrook, the situation worsened for Hume.[26] In 1879 Hume went against the authorities.[7] The Government of Lord Lytton dismissed him from his position in the Secretariat. No clear reason was given except that it "was based entirely on the consideration of what was most desirable in the interests of the public service". The press declared that his main wrongdoing was that he was too honest and too independent. The Pioneer wrote that it was "the grossest jobbery ever perpetrated" ; the Indian Daily News wrote that it was a "great wrong" while The Statesman said that "undoubtedly he has been treated shamefully and cruelly." The Englishman in an article dated 27 June 1879, commenting on the event stated, "There is no security or safety now for officers in Government employment."[27] Demoted, he left Simla and returned to the North-West Provinces in October 1879, as a member of the Board of Revenue.[28] It has pointed out that he was victimised as he was out of step with the policies of the Government, often intruding into aspects of administration with critical opinions.[28]

Demotion and resignation (1879–1882)

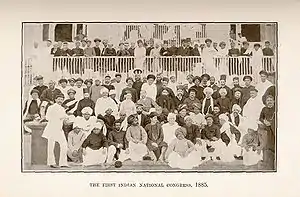

In spite of the humiliation of demotion, he did not resign immediately from service and it has been suggested that this was because he needed his salary to support the publication of The Game Birds of India that he was working on.[28] Hume retired from the civil service only in 1882. In 1883 he wrote an open letter to the graduates of Calcutta University, calling upon them to form their own national political movement. This led in 1885 to the first session of the Indian National Congress held in Bombay.[29] In 1887 writing to the Public Commission of India he made what was then a statement unexpected from a civil servant — I look upon myself as a Native of India.[28]

Return to England 1894

Hume's wife Mary died on 30 March 1890 and news of her death reached him just as he reached London on 1 April 1890.[30] Their only daughter Maria Jane Burnley ("Minnie") (1854–1927) had married Ross Scott at Shimla on 28 December 1881.[31] Maria became a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, another occult movement, after moving to England.[32] Ross Scott was the founding secretary of the Simla Eclectic Theosophical Society, who was sometime Judicial Commissioner of Oudh and died in 1908.[33] Hume's grandson Allan Hume Scott served with the Royal Engineers in India.

Hume left India in 1894 and settled at The Chalet, 4 Kingswood Road, Upper Norwood in south London. He died at the age of eighty-three on 31 July 1912. His ashes were buried in Brookwood Cemetery.[5] The bazaar in Etawah was closed on hearing of his death and the Collector, H. R. Neville, presided over a memorial meeting.[34]

The Indian postal department issued a commemorative stamp with his portrait in 1973 and a special cover depicting Rothney Castle, his home in Shimla, was released in 2013.

Contribution to ornithology and natural history

From early days, Hume had a special interest in science. Science, he wrote:

...teaches men to take an interest in things outside and beyond… The gratification of the animal instinct and the sordid and selfish cares of worldly advancement; it teaches a love of truth for its own sake and leads to a purely disinterested exercise of intellectual faculties

and of natural history he wrote in 1867:[8]

... alike to young and old, the study of Natural History in all its branches offers, next to religion, the most powerful safeguard against those worldly temptations to which all ages are exposed. There is no department of natural science the faithful study of which does not leave us with juster and loftier views of the greatness, goodness, and wisdom of the Creator, that does not leave us less selfish and less worldly, less spiritually choked up with those devil's thorns, the love of dissipation, wealth, power, and place, that does not, in a word, leave us wiser, better and more useful to our fellow-men.

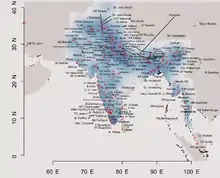

During his career in Etawah, he built up a personal collection of bird specimens, however the first collection that he made was destroyed during the 1857 rebellion. After 1857 Hume made several expeditions to collect birds both on health leave and where work took him but his most systematic work began after he moved to Shimla. He was Collector and Magistrate of Etawah from 1856 to 1867 during which time he studied the birds of that area. He later became Commissioner of Inland Customs which made him responsible for the control of 2,500 miles (4,000 km) of coast from near Peshawar in the northwest to Cuttack on the Bay of Bengal. He travelled on horseback and camel in areas of Rajasthan to negotiate treaties with various local maharajas to control the export of salt and during these travels he took note of the birdlife:

The nests are placed indifferently on all kinds of trees (I have notes of finding them on mango, plum, orange, tamarind, toon, etc.), never at any great elevation from the ground, and usually in small trees, be the kind chosen what it may. Sometimes a high hedgerow, such as our great Customs hedge, is chosen, and occasionally a solitary caper or stunted acacia-bush.

— On the nesting of the Bay-backed Shrike (Lanius vittatus) in The Nests and Eggs of Indian Birds.

Hume appears to have planned a comprehensive work on the birds of India around 1870 and a "forthcoming comprehensive work" finds mention in the second edition of The Cyclopaedia of India (1871) by his cousin Edward Balfour.[35] His systematic plan to survey and document the birds of the Indian Subcontinent began in earnest after he started accumulating the largest collection of Asiatic birds in his personal museum and library at home in Rothney Castle on Jakko Hill, Simla. Rothney Castle, originally Rothney House was built by Colonel Octavius Edward Rothney and later belonged to P. Mitchell, C.I.E from whom Hume bought it and converted it into a palatial house with some hope that it might be bought by the Government as a Viceregal residence since the Governor-General then occupied Peterhoff, a building too small for large parties. Hume spent over two hundred thousand pounds on the grounds and buildings. He added enormous reception rooms suitable for large dinner parties and balls, as well as a magnificent conservatory and spacious hall with walls displaying his superb collection of Indian horns. He used a large room for his bird museum. He hired a European gardener, and made the grounds and conservatory a perpetual horticultural exhibition, to which he courteously admitted all visitors. Rothney Castle could only be reached by a steep road, and was never purchased by the British Government.[8][36]

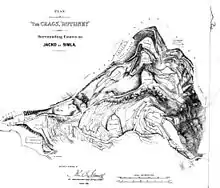

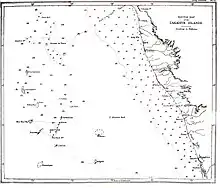

Hume made several expeditions almost solely to study ornithology the largest being an expedition to the Indus area in late November 1871 and continued until the end of February 1872. In March 1873, he visited the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal along with geologists Dr. Ferdinand Stoliczka and Dr. Dougall of the Geological Survey of India and James Wood-Mason of the Indian Museum in Calcutta. In 1875, he made an expedition to the Laccadive Islands aboard the marine survey vessel IGS Clyde under the command of Staff-Commander Ellis. The official purpose of the visit being to examine proposed sites for lighthouses. During this expedition Hume collected many bird specimens, apart from conducting a bathymetric survey to determine whether the island chain was separated from India by a deep canyon.[37][38] And in 1881 he made his last ornithological expedition to Manipur, a visit in which he collected and described the Manipur bush quail (Perdicula manipurensis), a bird that has remained obscure with few reliable reports since. Hume spent an extra day with his assistants cutting down a large tract of grass so that he could obtain specimens of this species.[39] This expedition was made on special leave following his demotion from the Central Government to a junior position on the Board of Revenue of the North Western Provinces.[8] Apart from personal travel, he also sent out a trained bird-skinner to accompany officers travelling in areas of ornithological interest such as Afghanistan.[40] Around 1878 he was spending about £1500 a year on his ornithological surveys.[28]

Hume was a member of the Asiatic Society of Bengal from January 1870 to 1891[41][42] and admitted Fellow of the Linnean Society on 3 November 1904.[43] After returning to England in 1890 he also became president of the Dulwich Liberal and Radical Association.[44]

Collection

Hume used his vast bird collection to good use as editor of his journal Stray Feathers. He also intended to produce a comprehensive publication on the birds of India. Hume employed William Ruxton Davison, who was brought to notice by Dr. George King, as a curator for his personal bird collection. Hume trained Davison and sent him out annually on collection trips to various parts of India as he himself was held up with official responsibilities.[8] In 1883 Hume returned from a trip to find that many pages of the manuscripts that he had maintained over the years had been stolen and sold off as waste paper by a servant. Hume was completely devastated and he began to lose interest in ornithology due to this theft and a landslip, caused by heavy rains in Simla, which had damaged his museum and many of the specimens. He wrote to the British Museum wishing to donate his collection on certain conditions. One of the conditions was that the collection was to be examined by Dr. R. Bowdler Sharpe and personally packed by him, apart from raising Dr. Sharpe's rank and salary due to the additional burden on his work caused by his collection. The British Museum was unable to heed his many conditions. It was only in 1885 after the destruction of nearly 20000 specimens, that alarm bells were raised by Dr. Sharpe and the museum authorities let him visit India to supervise the transfer of the specimens to the British Museum.[8]

Sharpe wrote of Hume's impressive private ornithological museum:[8][45]

I arrived at Rothney Castle about 10 am on the 19th of May, and was warmly welcomed by Mr Hume, who lives in a most picturesque situation high up on Jakko…From my bedroom window, I had a fine view of the snowy range. Although somewhat tired by my jolt in the Tonga from Solun, I gladly accompanied Mr. Hume at once into the museum…I had heard so much from my friends, who knew the collection intimately,…that I was not so much surprised when at last I stood in the celebrated museum and gazed at the dozens upon dozens of tin cases which filled the room. Before the landslip occurred, which carried away one end of the museum, It must have been an admirably arranged building, quite three times as large as our meeting-room at the Zoological Society, and…much more lofty. Throughout this large room went three rows of table cases with glass tops, in which were arranged a series of the birds of India sufficient for the identification of each species, while underneath these table- cases where enormous cabinets made of tin, with trays inside, containing species of birds in the table cases above. All of the rooms were racks reaching up to the ceiling, and containing immense cases full of birds… On the western side of the museum was the library, reached by a descent of three steps, a cheerful room, furnished with large tables, and containing besides the egg-cabinets, a well-chosen set of working-volumes. One ceases to wonder at the amount of work its owner got through when the excellent plan of his museum is considered. In a few minutes an immense series of specimens could be spread out on the tables, while all the books were at hand for immediate reference…After explaining to me the contents of the museum, we went below into the basement, which consisted of eight great rooms, six of them full, from floor to ceiling, of cases of birds, while at the back of the house two large verandahs were piled high with cases full of large birds, such as Pelicans, Cranes, Vultures, &c. An inspection of a great cabinet containing a further series of about 5000 eggs completed our survey. Mr. Hume gave me the keys of the museum, and I was free to commence my task at once.

Mr. Hume was a naturalist of no ordinary calibre, and this great collection will remain a monument of his genius and energy of its founder long after he who formed it has passed away...Such a private collection as Mr. Hume's is not likely to be formed again; for it is doubtful if such a combination of genius for organisation with energy for the completion of so great a scheme, and the scientific knowledge requisite for its proper development will again be combined in a single individual.

The Hume collection of birds was packed into 47 cases made of deodar wood constructed on site without nails that could potentially damage specimens and each case weighing about half a ton was transported down the hill to a bullock cart to Kalka and finally the port in Bombay. The material that went to the British Museum in 1885 consisted of 82,000 specimens of which 75,577 were finally placed in the museum. A breakup of that collection is as follows (old names retained).[8] Hume had destroyed 20,000 specimens prior to this as they had been damaged by dermestid beetles.[45]

- 2830 birds of prey (Accipitriformes)... 8 types

- 1155 owls (Strigiformes)...9 types

- 2819 crows, jays, orioles etc....5 types

- 4493 cuckoo-shrikes and flycatchers... 21 types

- 4670 thrushes and warblers...28 types

- 3100 bulbuls and wrens, dippers, etc....16 types

- 7304 timaliine birds...30 types

- 2119 tits and shrikes...9 types

- 1789 sun-birds (Nectarinidae) and white-eyes (Zosteropidae)...8 types

- 3724 swallows (Hirundiniidae), wagtails and pipits (Motacillidae)...8 types

- 2375 finches (Fringillidae)...8 types

- 3766 starlings (Sturnidae), weaver-birds (Ploceidae), and larks (Alaudidae)...22 types

- 807 ant-thrushes (Pittidae), broadbills (Eurylaimidae)...4 types

- 1110 hoopoes (Upupae), swifts (Cypseli), nightjars (Caprimulgidae) and frogmouths (Podargidae)...8 types

- 2277 Picidae, hornbills (Bucerotes), bee-eaters (Meropes), kingfishers (Halcyones), rollers(Coracidae), trogons (trogones)...11 types

- 2339 woodpeckers (Pici)...3 types

- 2417 honey-guides (Indicatores), barbets (Capiformes), and cuckoos (Coccyges)...8 types

- 813 parrots (Psittaciformes)...3 types

- 1615 pigeons (Columbiformes)...5 types

- 2120 sand-grouse (Pterocletes), game-birds and megapodes(Galliformes)...8 types

- 882 rails (Ralliformes), cranes (Gruiformes), bustards (Otides)...6 types

- 1089 ibises (Ibididae), herons (Ardeidae), pelicans and cormorants (Steganopodes), grebes (Podicipediformes)...7 types

- 761 geese and ducks (Anseriformes)...2 types

- 15965 eggs

The Hume Collection contained 258 type specimens. In addition there were nearly 400 mammal specimens including new species such as Hadromys humei.[46]

The egg collection was made up of carefully authenticated contributions from knowledgeable contacts and on the authenticity and importance of the collection, E. W. Oates wrote in the 1901 Catalogue of the Collection of Birds' Eggs in the British Museum (Volume 1):

The Hume Collection consists almost entirely of the eggs of Indian birds. Mr. Hume seldom or never purchased a specimen, and the large collection brought together by him in the course of many years was the result of the willing co-operation of numerous friends resident in India and Burma. Every specimen in the collection may be said to have been properly authenticated by a competent naturalist; and the history of most of the clutches has been carefully recorded in Mr. Hume's 'Nests and Eggs of Indian Birds', of which two editions have been published.

Hume and his collector Davison took an interest in plants as well. Specimens were collected even on the first expedition to the Lakshadweep in 1875 were studied by George King and later by David Prain. Hume's herbarium specimens were donated to the collection of the Botanical Survey of India at Calcutta.[47]

Taxa described

Hume described many species, some of which are now considered as subspecies. A single genus name that he erected survives in use while others such as Heteroglaux Hume, 1873 have sunk into synonymy since.[8][48][1] In his concept of species, Hume was an essentialist and held the idea that small but constant differences defined species. He appreciated the ideas of speciation and how it contradicted divine creation but preferred to maintain a position that did not reject a Creator.[49][50]

- Genera

- Ocyceros Hume, 1873

- Species

- Anas albogularis (Hume, 1873)

- Perdicula manipurensis Hume, 1881

- Arborophila mandellii Hume, 1874

- Syrmaticus humiae (Hume, 1881)

- Puffinus persicus Hume, 1872

- Ardea insignis Hume, 1878

- Pseudibis davisoni (Hume, 1875)

- Gyps himalayensis Hume, 1869

- Spilornis minimus Hume, 1873

- Buteo burmanicus Hume, 1875

- Sternula saundersi (Hume, 1877)

- Columba palumboides (Hume, 1873)

- Phodilus assimilis Hume, 1877

- Otus balli (Hume, 1873)

- Otus brucei (Hume, 1872)

- Strix butleri (Hume, 1878)

- Heteroglaux blewitti Hume, 1873

- Ninox obscura Hume, 1872

- Tyto deroepstorffi (Hume, 1875)

- Caprimulgus andamanicus Hume, 1873

- Aerodramus maximus (Hume, 1878)

- Psittacula finschii (Hume, 1874)

- Hydrornis oatesi Hume, 1873

- Hydrornis gurneyi (Hume, 1875)

- Rhyticeros narcondami Hume, 1873

- Megalaima incognita Hume, 1874

- Podoces hendersoni Hume, 1871

- Podoces biddulphi Hume, 1874

- Pseudopodoces humilis (Hume, 1871)

- Mirafra microptera Hume, 1873

- Alcippe dubia (Hume, 1874)

- Stachyridopsis rufifrons (Hume, 1873)

- Cyornis olivaceus Hume, 1877

- Oenanthe albonigra (Hume, 1872)

- Dicaeum virescens Hume, 1873

- Pyrgilauda blanfordi (Hume, 1876)

- Ploceus megarhynchus Hume, 1869

- Spinus thibetanus (Hume, 1872)

- Carpodacus stoliczkae (Hume, 1874)

- Gampsorhynchus torquatus Hume, 1874

- Sylvia minula Hume, 1873

- Sylvia althaea Hume, 1878

- Phylloscopus neglectus Hume, 1870

- Horornis brunnescens (Hume, 1872)

- Yuhina humilis (Hume, 1877)

- Pteruthius intermedius (Hume, 1877)

- Certhia manipurensis Hume, 1881

- Calandrella acutirostris Hume, 1873

- Pycnonotus fuscoflavescens (Hume, 1873)

- Pycnonotus erythropthalmos (Hume, 1878)

- Subspecies

The use of trinomials had not yet gone into regular usage during Hume's time. He used the term "local race".[50] The following subspecies are current placements of taxa that were named as new species by Hume.

- Alectoris chukar pallida (Hume, 1873)

- Alectoris chukar pallescens (Hume, 1873)

- Francolinus francolinus melanonotus Hume, 1888

- Perdicula erythrorhyncha blewitti (Hume, 1874)

- Arborophila rufogularis tickelli (Hume, 1880)

- Phaethon aethereus indicus Hume, 1876

- Gyps fulvus fulvescens Hume, 1869

- Spilornis cheela davisoni Hume, 1873

- Accipiter badius poliopsis (Hume, 1874)

- Accipiter nisus melaschistos Hume, 1869

- Rallina eurizonoides telmatophila Hume, 1878

- Gallirallus striatus obscurior (Hume, 1874)

- Sterna dougallii korustes (Hume, 1874)

- Columba livia neglecta Hume, 1873

- Macropygia ruficeps assimilis Hume, 1874

- Centropus sinensis intermedius (Hume, 1873)

- Otus spilocephalus huttoni (Hume, 1870)

- Otus lettia plumipes (Hume, 1870)

- Otus sunia nicobaricus (Hume, 1876)

- Bubo bubo hemachalanus Hume, 1873

- Strix leptogrammica ochrogenys (Hume, 1873)

- Strix leptogrammica maingayi (Hume, 1878)

- Athene brama pulchra Hume, 1873

- Ninox scutulata burmanica Hume, 1876

- Lyncornis macrotis bourdilloni Hume, 1875

- Caprimulgus europaeus unwini Hume, 1871

- Aerodramus brevirostris innominatus (Hume, 1873)

- Aerodramus fuciphagus inexpectatus (Hume, 1873)

- Hirundapus giganteus indicus (Hume, 1873)

- Lacedo pulchella amabilis (Hume, 1873)

- Pelargopsis capensis intermedia Hume, 1874

- Halcyon smyrnensis saturatior Hume, 1874

- Megalaima asiatica davisoni Hume, 1877

- Dendrocopos cathpharius pyrrhothorax (Hume, 1881)

- Picus erythropygius nigrigenis (Hume, 1874)

- Falco cherrug hendersoni Hume, 1871

- Pericrocotus brevirostris neglectus Hume, 1877

- Pericrocotus speciosus flammifer Hume, 1875

- Dicrurus andamanensis dicruriformis (Hume, 1873)

- Rhipidura aureola burmanica (Hume, 1880)

- Garrulus glandarius leucotis Hume, 1874

- Dendrocitta formosae assimilis Hume, 1877

- Corvus splendens insolens Hume, 1874

- Corvus corax laurencei Hume, 1873

- Coracina melaschistos intermedia (Hume, 1877)

- Coracina fimbriata neglecta (Hume, 1877)

- Remiz coronatus stoliczkae (Hume, 1874)

- Alauda arvensis dulcivox Hume, 1872

- Alaudala raytal adamsi (Hume, 1871)

- Galerida cristata magna Hume, 1871

- Pycnonotus squamatus webberi (Hume, 1879)

- Pycnonotus finlaysoni davisoni (Hume, 1875)

- Alophoixus pallidus griseiceps (Hume, 1873)

- Hemixos flavala hildebrandi Hume, 1874

- Hemixos flavala davisoni Hume, 1877

- Ptyonoprogne obsoleta pallida Hume, 1872

- Aegithalos concinnus manipurensis (Hume, 1888)

- Leptopoecile sophiae stoliczkae (Hume, 1874)

- Prinia crinigera striatula (Hume, 1873)

- Prinia inornata terricolor (Hume, 1874)

- Prinia sylvatica insignis (Hume, 1872)

- Orthotomus atrogularis nitidus Hume, 1874

- Rhopocichla atriceps bourdilloni (Hume, 1876)

- Pomatorhinus hypoleucos tickelli Hume, 1877

- Pomatorhinus horsfieldii obscurus Hume, 1872

- Pomatorhinus ochraceiceps austeni Hume, 1881

- Stachyridopsis rufifrons poliogaster (Hume, 1880)

- Alcippe poioicephala brucei Hume, 1870

- Pellorneum albiventre ignotum Hume, 1877

- Pellorneum ruficeps minus Hume, 1873

- Turdoides caudata eclipes (Hume, 1877)

- Garrulax caerulatus subcaerulatus Hume, 1878

- Trochalopteron chrysopterum erythrolaemum Hume, 1881

- Trochalopteron variegatum simile Hume, 1871

- Minla cyanouroptera sordida (Hume, 1877)

- Minla strigula castanicauda (Hume, 1877)

- Heterophasia annectans davisoni (Hume, 1877)

- Chrysomma altirostre griseigulare (Hume, 1877)

- Rhopophilus pekinensis albosuperciliaris (Hume, 1873)

- Zosterops palpebrosus auriventer Hume, 1878

- Yuhina castaniceps rufigenis (Hume, 1877)

- Aplonis panayensis tytleri (Hume, 1873)

- Sturnus vulgaris nobilior Hume, 1879

- Sturnus vulgaris minor Hume, 1873

- Copsychus saularis andamanensis Hume, 1874

- Anthipes solitaris submoniliger Hume, 1877

- Cyornis concretus cyaneus (Hume, 1877)

- Ficedula tricolor minuta (Hume, 1872)

- Myophonus caeruleus eugenei Hume, 1873

- Geokichla sibirica davisoni (Hume, 1877)

- Dicaeum agile modestum (Hume, 1875)

- Cinnyris asiaticus intermedius (Hume, 1870)

- Cinnyris jugularis andamanicus (Hume, 1873)

- Aethopyga siparaja cara Hume, 1874

- Aethopyga siparaja nicobarica Hume, 1873

- Passer ammodendri stoliczkae Hume, 1874

- Lonchura striata semistriata (Hume, 1874)

- Lonchura kelaarti jerdoni (Hume, 1874)

- Linaria flavirostris montanella (Hume, 1873)

An additional species, the large-billed reed-warbler Acrocephalus orinus was known from just one specimen collected by him in 1869 but the name that he used, magnirostris, was found to be preoccupied and replaced by the name orinus provided by Harry Oberholser in 1905.[51] The status of the species was contested until DNA comparisons with similar species in 2002 suggested that it was a valid species.[52] It was only in 2006 that the species was seen in the wild in Thailand, with a match to the specimens confirmed using DNA sequencing. Later searches in museums led to several other specimens that had been overlooked and based on the specimen localities, a breeding region was located in Tajikistan and documented in 2011.[53][54]

My Scrap Book: Or Rough Notes on Indian Oology and Ornithology (1869)

This was Hume's first major work on birds. It had 422 pages and accounts of 81 species. It was dedicated to Edward Blyth and Dr. Thomas C. Jerdon who, he wrote [had] done more for Indian Ornithology than all other modern observers put together and he described himself as their friend and pupil. He hoped that his book would form a nucleus round which future observation may crystallize and that others around the country could help him fill in many of the woeful blanks remaining in record. In the preface he notes:

...if these notes chance to be of the slightest use to you, use them; if not burn them, if it so please you, but do not waste your time in abusing me or them, since no one can think more poorly of them than I do myself.

Stray Feathers

Hume started the quarterly journal Stray Feathers in 1872. At that time the only journal for the Indian region that published on ornithology was the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal and Hume published only two letters in 1870, mainly being a list of errors in the list of Godwin-Austen which had been reduced to an abstract.[56] He had wondered if there was merit to start a new journal and in that idea was supported by Stoliczka, who was an editor for the Journal of the Asiatic Society:

To return; the notion that Stray Feathers might possibly interfere in any way with our scientific palladium, the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, is much like that entertained in England, when I was a boy, as to the probable effects of Railways on road and canal traffic.

— Hume, 1874[57]

The President of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Thomas Oldham, in the annual address for 1873 wrote - "We could have wished that the author had completed the several works which he had already commenced, rather than started a new publication. But we heartily welcome at the same time the issue of 'Stray Feathers.' It promises to be a useful catalogue of the Editor's very noble collection of Indian Birds, and a means of rapid publication of novelties or corrections, always of much value with ornithologists."[58] Hume used the journal to publish descriptions of his new discoveries. He wrote extensively on his own observation as well as critical reviews of all the ornithological works of the time and earned himself the nickname of Pope of Indian ornithology. He critiqued a monograph on parrots, Die Papageien by Friedrich Hermann Otto Finsch suggesting that name changes (by "cabinet naturalists") were aimed at claiming authority to species without the trouble of actually discovering them. He wrote:

Let us treat our author as he treats other people's species. “Finsch!” contrary to all rules of orthography! What is that “s” doing there? “Finch!” Dr. Fringilla, MIHI! Classich gebildetes wort!!

— Hume, 1874[59]

Hume in turn was attacked, for instance by Viscount Walden, but Finsch became a friend and Hume named a species, Psittacula finschii, after him.[60][61]

In his younger days Hume had studied some geology from the likes of Gideon Mantell[62] and appreciated the synthesis of ideas from other fields into ornithology. Hume included in 1872, a detailed article on the osteology of birds in relation to their classification written by Richard Lydekker who was then in the Geological Survey of India.[63] The early meteorological work in India was done within the department headed by Hume and he saw the value of meteorology in the study of bird distributions. In a work comparing the rainfall zones, he notes how the high rainfall zones indicated affinities to the Malayan fauna.[64][65]

Hume sometimes mixed personal beliefs in notes that he published in Stray Feathers. For instance he believed that vultures soared by altering the physics ("altered polarity") of their body and repelling the force of gravity. He further noted that this ability was normal in birds and could be acquired by humans by maintaining spiritual purity claiming that he knew of at least three Indian Yogis and numerous saints in the past with this ability of aethrobacy.[66][67]

Network of correspondents

Hume corresponded with a large number of ornithologists and sportsmen who helped him by reporting from various parts of India. More than 200 correspondents are listed in his Game Birds alone and they probably represent only a fraction of the subscribers of Stray Feathers. This large network made it possible for Hume to cover a much larger geographic region in his ornithological work.

During the lifetime of Hume, Blyth was considered the father of Indian ornithology. Hume's achievement which made use of a large network of correspondents was recognised even during his time:

Mr. Blyth, who is rightly called the Father of Indian Ornithology, "was by far the most important contributor to our knowledge of the Birds of India." Seated, as the head of the Asiatic Society's Museum, he, by intercourse and through correspondents, not only formed a large collection for the Society, but also enriched the pages of the Society's Journal with the results of his study, and thus did more for the extension of the study of the Avifauna of India than all previous writers. There can be no work on Indian Ornithology without reference to his voluminous contributions. The most recent authority, however, is Mr. Allen O. Hume, C.B., who, like Blyth and Jerdon, got around him numerous workers, and did so much for Ornithology, that without his Journal Stray Feathers, no accurate knowledge could be gained of the distribution of Indian birds. His large museum, so liberally made over to the nation, is ample evidence of his zeal and the purpose to which he worked. Ever saddled with his official work, he yet found time for carrying out a most noble object. His Nests and Eggs, Scrap Book and numerous articles on birds of various parts of India, the Andamans and the Malay Peninsula, are standing monuments of his fame throughout the length and breadth of the civilised world. His writings and the field notes of his curator, contributors and collectors are the pith of every book on Indian Birds, and his vast collection is the ground upon which all Indian Naturalists must work. Though differing from him on some points, yet the palm is his as an authority above the rest in regard to the Ornis of India. Amongst the hundred and one contributors to the Science in the pages of Stray Feathers, there are some who may be ranked as specialists in this department, and their labors need a record. These are Mr. W. T. Blanford, late of the Geological Survey, an ever watchful and zealous Naturalist of some eminence. Mr. Theobald, also of the Geological Survey, Mr. Ball of the same Department, and Mr. W. E. Brooks. All these worked in Northern India, while for work in the Western portion must stand the names of Major Butler, of the 66th Regiment, Mr. W. F. Sinclair, Collector of Colaba, Mr. G. Vidal, the Collector of Bombay, Mr. J. Davidson, Collector of Khandeish, and Mr. Fairbank, each one having respectively worked the Avifauna of Sind, the Concan, the Deccan and Khandeish.

— James Murray[69]

Many of Hume's correspondents were eminent naturalists and sportsmen who were posted in India.

- Leith Adams, Kashmir

- Lieut. H. E. Barnes, Afghanistan, Chaman, Rajpootana

- Captain R. C. Beavan, Maunbhoom District, Shimla, Mount Tongloo (1862)

- Colonel John Biddulph, Gilgit

- Dr. George Bidie, Madras

- Major C. T. Bingham, Thoungyeen Valley, Burma, Tenasserim, Moulmein, Allahabad

- Mr. W. Blanford

- Mr. Edward Blyth

- Dr. Emmanuel Bonavia, Lucknow

- Mr. W. Edwin Brooks (father of Allan Brooks, the Canadian bird artist)

- Sir Edward Charles Buck, Gowra, Hatu, near Narkanda (in Himachal Pradesh), Narkanda, (about 30 miles (48 km) north of Shimla)

- Captain Boughey Burgess, Ahmednagar (?-1855)[70]

- Captain and then Colonel E. A. Butler, Belgaum (1880), Karachi, Deesa, Abu

- Miss Cockburn (1829–1928), Kotagiri

- Mr. James Davidson, Satara and Sholapur districts, Khandeish, Kondabhari Ghat

- Colonel Godwin-Austen, Shillong, Umian valley, Assam

- Mr. Brian Hodgson, Nepal

- Duncan Charles Home, 'Hero of the Kashmir Gate' (Bulandshahr, Aligarh)

- Dr. T. C. Jerdon, Tellicherry

- Colonel C. H. T. Marshall, Bhawulpoor, Murree

- Colonel G. F. L. Marshall, Nainital, Bhim tal

- Mr. James A. Murray, Karachi Museum

- Mr. Eugene Oates, Thayetmo, Tounghoo, Pegu

- Captain Robert George Wardlaw Ramsay, Afghanistan, Karenee hills

- Frederik Adolph de Roepstorff, Andaman and Nicobar Islands

- Mr. G. P. Sanderson (Chittagong)

- Major and later Sir O. B. St. John, Shiraz, Persia

- Dr. Ferdinand Stoliczka

- Mr. Robert Swinhoe, Hong Kong

- Mr. Charles Swinhoe, S. Afghanistan

- Colonel Samuel Tickell

- Colonel Robert Christopher Tytler, Dacca, 1852

- Mr. Valentine Ball, Rajmahal hills, Subanrika (Subansiri)

- Richard Lydekker, geologist

- G. W. Vidal, civil servant in South Konkan, Bombay

Hume exchanged skins with other collectors. A collection made principally by Hume that belonged to the Earl of Northbrook was gifted to Oxford University in 1877.[71] One of his correspondents, Louis Mandelli from Darjeeling, stands out by claiming that he was swindled in these skin exchanges. He claimed that Hume took skins of rarer species in exchange for the skins of common birds but the credibility of the complaint has been doubted. Hume named Arborophila mandelli after Mandelli in 1874.[1] The only other naturalist to question Hume's veracity was A.L. Butler who met a Nicobar islander whom Hume had described as diving nearly stark naked and capturing fish with his bare hands. Butler found the man in denial of such fishing techniques.[72]

Hume corresponded and stayed up to date with the works of ornithologists outside India including R. Bowdler Sharpe, the Marquis of Tweeddale, Père David, Henry Eeles Dresser, Benedykt Dybowski, John Henry Gurney, J. H. Gurney, Jr., Johann Friedrich Naumann, Nikolai Severtzov and Dr. Aleksandr Middendorff. He helped George Ernest Shelley with specimens from India aiding the publication of a monograph on the sunbirds of the world (1876–1880).[73]

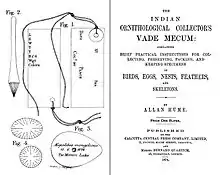

Collector's Vade Mecum (1874)

Hume's vast collection from across India was possible because he began to correspond with coadjutors across India. He ensured that these contributors made accurate notes, and obtained and processed specimens carefully. The Vade Mecum was published to save him the trouble of sending notes to potential collaborators who sought advice. Materials for preservation are carefully tailored for India with the provision of the local names for ingredients and methods to prepare glues and preservatives with easy to find equipment. Apart from skinning and preservation, the book also covers matters of observation, keeping records, the use of natives to capture birds, obtain eggs and the care needed in obtaining other information apart from care in labelling.[74]

Game Birds of India, Burmah and Ceylon (1879–1881)

This work was co-authored by C. H. T. Marshall. The three volume work on the game birds was made using contributions and notes from a network of 200 or more correspondents. Hume delegated the task of getting the plates made to Marshall. The chromolithographs of the birds were drawn by W. Foster, E. Neale, (Miss) M. Herbert, Stanley Wilson and others and the plates were produced by F. Waller in London. Hume had sent specific notes on colours of soft parts and instructions to the artists. He was dissatisfied with many of the plates and included additional notes on the plates in the book. This book was started at the point when the government demoted Hume and only the need to finance the publication of this book prevented him from retiring from service. He had estimated that it would cost £4000 to publish it and he retired from service on 1 January 1882 after the publication.[2][28]

In the preface Hume wrote:

In the second place, we have had great disappointment in artists. Some have proved careless, some have subordinated accuracy of delineation to pictorial effect, and though we have, at some loss, rejected many, we have yet been compelled to retain some plates which are far from satisfactory to us.

while his co-author Marshall, wrote:

I have performed my portion of the work to the very best of my abilities, and yet personally felt almost as if I were sailing under false colors in appearing before the world as one of the authors of this book; but I allow my name to appear as such, partly because Mr. Hume strongly wishes it, partly because I do believe that as Mr. Hume says this work, which has been for years called for, would never have appeared had I not proceeded to England, and arranged for the preparation of the plates, and partly because with the explanation thus afforded no one can justly misconstrue my action.

Nests and Eggs of Indian Birds (1883)

This was another major work by Hume and in it he covered descriptions of the nests, eggs and the breeding seasons of most Indian bird species. It makes use of notes from contributors to his journals as well as other correspondents and works of the time. Hume also makes insightful notes such as observations on caged females separated from males that would continue to lay fertile eggs through the possibility of sperm storage[75] and the reduction in parental care by birds that laid eggs in warm locations (mynas in the Andamans, river terns on sand banks).[76]

A second edition of this book was made in 1889 which was edited by Eugene William Oates. This was published when he had himself given up all interest in ornithology. An event precipitated by the loss of his manuscripts through the actions of a servant. He wrote in the preface:

I have long regretted my inability to issue a revised edition of 'Nests and Eggs'. For many years after the first Rough Draft appeared, I went on laboriously accumulating materials for a re-issue, but subsequently circumstances prevented my undertaking the work. Now, fortunately, my friend Mr. Eugene Oates has taken the matter up, and much as I may personally regret having to hand over to another a task, the performance of which I should so much have enjoyed, it is some consolation to feel that the readers, at any rate, of this work will have no cause for regret, but rather of rejoicing that the work has passed into younger and stronger hands. One thing seems necessary to explain. The present Edition does not include quite all the materials I had accumulated for this work. Many years ago, during my absence from Simla, a servant broke into my museum and stole thence several cwts. of manuscript, which he sold as waste paper. This manuscript included more or less complete life-histories of some 700 species of birds, and also a certain number of detailed accounts of nidification. All small notes on slips of paper were left, but almost every article written on full-sized foolscap sheets was abstracted. It was not for many months that the theft was discovered, and then very little of the MSS. could be recovered.

— Rothney Castle, Simla, October 19th, 1889

Eugene Oates wrote his own editorial note:

Mr. Hume has sufficiently explained the circumstances under which this edition of his popular work has been brought about. I have merely to add that, as I was engaged on a work on the Birds of India, I thought it would be easier for me than for anyone else to assist Mr. Hume. I was also in England, and knew that my labour would be very much lightened by passing the work through the press in this country. Another reason, perhaps the most important, was the fear that, as Mr. Hume had given up entirely and absolutely the study of birds, the valuable material he had taken such pains to accumulate for this edition might be irretrievably lost or further injured by lapse of time unless early steps were taken to utilize it.

This nearly marked the end of Hume's interest in ornithology. Hume's last piece of ornithological writing was part of an Introduction to the Scientific Results of the Second Yarkand Mission in 1891, an official publication on the contributions of Dr. Ferdinand Stoliczka, who died during the return journey on this mission. Stoliczka in a dying request had asked that Hume edit the volume on ornithology.[8]

Taxa named after Hume

A number of birds are named after Hume, including:

- Hume's ground tit, Pseudopodoces humilis

- Hume's wheatear, Oenanthe albonigra

- Hume's hawk-owl, Ninox obscura

- Hume's short-toed lark, Calandrella acutirostris

- Hume's leaf warbler, Phylloscopus humei[77]

- Hume's whitethroat, Sylvia althaea

- Hume's treecreeper, Certhia manipurensis

Specimens of other animal groups collected by Hume on his expeditions and named after him include the Manipur bush rat, Hadromys humei (Thomas, 1886)[46] while some others like Hylaeocarcinus humei, a land crab from the Narcondam Island collected by Hume was described by James Wood-Mason,[78] and Hume's argali, Ovis ammon humei Lydekker 1913[79] (now treated as Ovis ammon karelini, Severtzov, 1873)[80] are no longer considered valid.

Theosophy

Hume's interest in theosophy took root around 1879. An 1880 newspaper reports the initiation of his daughter and wife into the movement.[81] Hume did not have great regard for institutional Christianity, but believed in the immortality of the soul and in the idea of a supreme ultimate.[2] Hume wanted to become a chela (student) of the Tibetan spiritual gurus. During the few years of his connection with the Theosophical Society Hume wrote three articles on Fragments of Occult Truth under the pseudonym "H. X." published in The Theosophist. These were written in response to questions from Mr. Terry, an Australian Theosophist.

He also privately printed several Theosophical pamphlets titled Hints on Esoteric Theosophy. The later numbers of the Fragments, in answer to the same enquirer, were written by A.P. Sinnett and signed by him, as authorized by Mahatma K. H., A Lay-Chela.[82] Hume also wrote under the pseudonym of "Aletheia".[83]

Madame Blavatsky was a regular visitor at Hume's Rothney castle at Simla and an account of her visit may be found in Simla, Past and Present by Edward John Buck (whose father Sir Edward Charles Buck succeeded Mr. Hume's role in the Revenue and Agricultural Department).[84]

A long story about Hume and his wife appears in A.P. Sinnett's book The Occult World,[85] and the synopsis was published in a local paper of India. The story relates how at a dinner party, Madame Blavatsky asked Mrs Hume if there was anything she wanted. She replied that there was a brooch, her mother had given her, that had gone out of her possession some time ago. Blavatsky said she would try to recover it through occult means. After some interlude, later that evening, the brooch was found in a garden, where the party was directed by Blavatsky. According to John Murdoch (1894), the brooch had been given by Mrs. Hume to her daughter who had given it to a man she admired. Blavatsky had happened to meet the man in Bombay and obtained the brooch in return for money. Blavatsky allegedly planted it in the garden before directing people to the location through what she claimed as occult techniques.[86]

After the incident, Hume too had privately expressed grave doubts on the powers attributed to Madame Blavatsky. He subsequently held a meeting with some of the Indian members of the Theosophical Society and suggested that they join hands with him to force the resignation of Blavatsky and sixteen other members for their role as accomplices in fraud. Those present could however not agree to the idea of seeking the resignation of their founder.[87] Hume also tried to write a book on the philosophical basis of Theosophy. His drafts were strongly disapproved by many of the key Theosophists. One ("K.H"=Koot Humi) wrote:

I dread the appearance in print of our philosophy as expounded by Mr. H. I read his three essays or chapters on God (?)cosmogony and glimpses of the origin of tings in general, and had to cross out nearly all. He makes of us Agnostics!! We do not believe in God because so far, we have no proof, etc. This is preposterously ridiculous: if he publishes what I read, I will have H.P.B. or Djual Khool deny the whole thing; as I cannot permit our sacred philosophy to be so disfigured....

— "K.H." (p.304)[87]

Hume soon fell out of favour with the Theosophists and lost all interest in the theosophical movement in 1883.[28]

Hume's interest in spirituality brought him into contact with many independent Indian thinkers[88] who also had nationalist ideas and this led to the idea of creating the Indian National Congress.[89]

Hume's immersion into the theosophical movement led him to become a vegetarian[90] and also to give up killing birds for their specimens.[8]

Indian National Congress

After retiring from the civil services and towards the end of Lord Lytton's rule, Hume observed that the people of India had a sense of hopelessness and wanted to do something, noting "a sudden violent outbreak of sporadic crime, murders of obnoxious persons, robbery of bankers and looting of bazaars, acts really of lawlessness which by a due coalescence of forces might any day develop into a National Revolt." Concerning the British government, he stated that a studied and invariable disregard, if not actually contempt for the opinions and feelings of our subjects, is at the present day the leading characteristic of our government in every branch of the administration.[91]

There were agrarian riots in the Deccan and Bombay, and Hume suggested that an Indian Union would be a good safety valve and outlet to avoid further unrest. On 1 March 1883 he wrote a letter to the graduates of the University of Calcutta:[29]

If only fifty men, good and true, can be found to join as founders, the thing can be established and the further development will be comparatively easy. ...

And if even the leaders of thought are all either such poor creatures, or so selfishly wedded to personal concerns that they dare not strike a blow for their country's sake, then justly and rightly are they kept down and trampled on, for they deserve nothing better. Every nation secures precisely as good a Government as it merits. If you the picked men, the most highly educated of the nation, cannot, scorning personal ease and selfish objects, make a resolute struggle to secure greater freedom for yourselves and your country, a more impartial administration, a larger share in the management of your own affairs, then we, your friends, are wrong and our adversaries right, then are Lord Ripon's noble aspirations for your good fruitless and visionary, then, at present at any rate all hopes of progress are at an end and India truly neither desires nor deserves any better Government than she enjoys. Only, if this be so, let us hear no more factious, peevish complaints that you are kept in leading strings and treated like children, for you will have proved yourself such. Men know how to act. Let there be no more complaining of Englishmen being preferred to you in all important offices, for if you lack that public spirit, that highest form of altruistic devotion that leads men to subordinate private ease to the public weal – that patriotism that has made Englishmen what they are – then rightly are these preferred to you, rightly and inevitably have they become your rulers. And rulers and task-masters they must continue, let the yoke gall your shoulders never so sorely, until you realise and stand prepared to act upon the eternal truth that self-sacrifice and unselfishness are the only unfailing guides to freedom and happiness.

In 1886 he published a pamphlet The Old Man's Hope in which he examined poverty in India and questioning charity as a solution for the problem.[92] Here he makes a case for Richard Cobden's Anti-Corn Law League as a model for the struggle in India through the formation of a representative body.[28]

His poem Awake published in Calcutta in 1886 also captures the sentiment:[93][94][95]

Sons of Ind, why sit ye idle,

Wait ye for some Deva's aid?

Buckle to, be up and doing!

Nations by themselves are made!

Yours the land, lives, all, at stake, tho '

Not by you the cards are played;

Are ye dumb? Speak up and claim them!

By themselves are nations made!

What avail your wealth, your learning,

Empty titles, sordid trade?

True self-rule were worth them all!

Nations by themselves are made!

Whispered murmurs darkly creeping,

Hidden worms beneath the glade,

Not by such shall wrong be righted!

Nations by themselves are made!

Are ye Serfs or are ye Freemen,

Ye that grovel in the shade?

In your own hands rest the issues!

By themselves are nations made!

Sons of Ind, be up and doing,

Let your course by none be stayed;

Lo! the Dawn is in the East;

By themselves are nations made!

The idea of the Indian National Union took shape and Hume initially had some support from Lord Dufferin for this, although the latter wished to have no official link to it. Dufferin's support was short-lived[96] and in some of his letters he went so far as to call Hume an "idiot", "arch-impostor", and "mischievous busy-body." Dufferin's successor Lansdowne refused to have any dialogue with Hume.[97] Other supporters in England included James Caird (who had also clashed with Lytton over the management of famine in India[98]) and John Bright.[99] Hume also founded an Indian Telegraph Union to fund the transfer of news of Indian matters to newspapers in England and Scotland without interference from British Indian officials who controlled telegrams sent by Reuters.[100] It has been suggested that the idea of the congress was originally conceived in a private meeting of seventeen men after a Theosophical Convention held at Madras in December 1884 but no evidence exists. Hume took the initiative, and it was in March 1885, when a notice was first issued to convene the first Indian National Union to meet at Poona the following December.[29]

He attempted to increase the Congress base by bringing in more farmers, townspeople and Muslims between 1886 and 1887 and this created a backlash from the British, leading to backtracking by the Congress. Hume was disappointed when Congress opposed moves to raise the age of marriage for Indian girls and failed to focus on issues of poverty. Some Indian princes did not like the idea of democracy and some organizations like the United Indian Patriotic Association went about trying to undermine the Congress by showing it as an organization with a seditious character.[101] In 1892, he tried to get them to act by warning of a violent agrarian revolution but this only outraged the British establishment and frightened the Congress leaders. Disappointed by the continued lack of Indian leaders willing to work for the cause of national emancipation, Hume left India in 1894.[2]

Many Anglo-Indians were against the idea of the Indian National Congress. The press in India tended to look upon it negatively, so much so that Hume is said to have held a very low opinion of journalists even later in life.[102] A satirical work published in 1888 included a character called "A. O. Humebogue".[103]

The organizers of the 27th session of the Indian National Congress at Bankipur (26–28 December 1912) recorded their "profound sorrow at the death of Allan Octavian Hume, C.B., father and founder of the Congress, to whose lifelong services, rendered at rare self-sacrifice, India feels deep and lasting gratitude, and in whose death the cause of Indian progress and reform sustained irreparable loss."[104][105]

South London Botanical Institute

After the loss of his manuscript containing his lifetime of ornithological notes, Hume gave up ornithology and took great interest in horticulture around his home in Shimla.

... He erected large conservatories in the grounds of Rothney Castle, filled them with the choicest flowers, and engaged English gardeners to help him in the work. From this, on returning to England, he went on to scientific botany. But this, as Kipling says, is another story, and must be left to another pen.[106]

Hume took an interest in wild plants and especially on invasive species although his botanical publishing was sparse with only a few short notes in 1901 on a variety of Scirpus maritimus and another on the flowering of Impatiens roylei. Hume contacted W.H. Griffin in 1901 to help develop a herbarium of botanical specimens. Hume would arrange his plants on herbarium sheets in artistic positions before pressing them. The two made many botanical trips including one to Down in Kent to seek some of the rare orchids that had been collected by Darwin.[107] In 1910, Hume bought the premises of 323 Norwood Road, and modified it to have a herbarium and library. He called this establishment the South London Botanical Institute (SLBI) with the aim of "promoting, encouraging, and facilitating, amongst the residents of South London, the study of the science of botany."

One of the aims of the institute was to help promote botany as a means for mental culture and relaxation, an idea that was not shared by Henry Groves, a trustee for the Institute.[108] Hume objected to advertisement and refused to have any public ceremony to open the institute. The first curator was W.H. Griffin and Hume endowed the Institute with £10,000. Frederick Townsend, F.L.S., an eminent botanist, who died in 1905, had left instructions that his herbarium and collection was to be given to the institute, which was then only being contemplated.[109] Hume left £15,000 in his will for the maintenance of the botanical institute.[44][110]

In the years leading up to the establishment of the Institute, Hume built up links with many of the leading botanists of his day. He worked with F. H. Davey and in the Flora of Cornwall (1909), Davey thanks Hume as his companion on excursions in Cornwall and Devon, and for help in the compilation of the 'Flora', publication of which was financed by Hume.[111] The SLBI has since grown to hold a herbarium of approximately 100,000 specimens mostly of flowering plants from Europe including many collected by Hume. The collection was later augmented by the addition of other herbaria over the years, and has significant collections of Rubus (bramble) species and of the Shetland flora.

Works

- My Scrap Book: Or Rough Notes on Indian Oology and Ornithology (1869)

- List of the Birds of India (1879)

- The Nests and Eggs of Indian Birds (3-volumes)

- with Marshall, Charles Henry Tilson (1879). The Game Birds of India, Burmah and Ceylon. Calcutta: A.O. Hume & C.H.T. Marshall. OCLC 5111667. Retrieved 15 April 2020. (3-volumes, 1879-1881)

- Hints on Esoteric Theosophy

- Agricultural Reform in India (1879)

- Lahore to Yarkand. Incidents of the Route and Natural History of the Countries Traversed by the Expedition of 1870 under T. D. Forsyth

- Stray Feathers (11-volumes + index by Charles Chubb)

References

- Collar, N. J.; Prys-Jones, R. P. (2012). "Pioneers of Asian ornithology. Allan Octavian Hume" (PDF). BirdingASIA. 17: 17–43.

- Moulton, Edward C. (2004). "Hume, Allan Octavian (1829–1912)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- Ali, S. (1979). Bird study in India: Its history and its importance. Azad Memorial lecture for 1978. Indian Council for Cultural Relations. New Delhi.

- Moulton (2004); Encyclopædia Britannica and some older sources give his birthplace as Montrose, Forfarshire.

- "Obituary". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. British Newspaper Archive. 1 August 1912. p. 8. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- "University of London". Morning Post. British Newspaper Archive. 16 July 1845. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- Wedderburn (1913):3.

- Moulton, Edward (2003). "The Contributions of Allan O. Hume to the Scientific Advancement of Indian Ornithology". In J. C. Daniel; G. W. Ugra (eds.). Petronia: Fifty Years of Post-Independence Ornithology in India. New Delhi, India: BNHS, Bombay & Oxford University Press. pp. 295–317.

- Keene, H.G. (1883). "Indian Districtions during the Revolt". The Army and Navy Magazine. 6: 97–109.

- Keene, Henry George (1883). Fifty-Seven. Some account of the administration of Indian Districts during the revolt of the Bengal Army. London: W.H.Allen and Co. pp. 58–67.

- Wedderburn (1913):11–12.

- Trevelyan, George (1895). The Competition Wallah. London: Macmillan and Co. p. 246.

- Wedderburn (1913):19.

- Wedderburn (1913):21.

- Memorandum by M. Kempson, Director of Public Instruction, NWP, dated 19-April-1870. Home Department Proceedings April, 1877. National Archives of India.

- Wedderburn (1913) spells Daniell.

- Wedderburn (1913):16.

- Wallach, Bret (1996). Losing Asia: Modernization and the Culture of Development (PDF). The Johns Hopkins Press.

- Footnote in Lydekker, 1913: This was a thorn-hedge supplemented by walls and ditches, and strongly patrolled for preventing the introduction into British territory of untaxed salt from native states (see Sir John Strachey's "India," London, 1888).

- Lydekker, R. (1913). Catalogue of the Heads and Horns of Indian Big Game bequeathed by A. O. Hume, C. B., to the British Museum. British Museum of Natural History.

- Markham, Clements R. (1878). A memoir on the Indian Surveys (2 ed.). London: W.H. Allen and Co. p. 307.

- Randhawa, M.S. (1983). A history of agriculture in India. Volume III. 1757–1947. New Delhi, India: Indian Council of Agricultural Research. pp. 172–186.

- Hovell-Thurlow, T.J. (1866). The Company and the Crown. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons. p. 89.

- Markham, Clements R. (1880). "Peruvian Bark. A popular account of the introduction of Chinchona cultivation into British India". Nature. 23 (583): 427–434. Bibcode:1880Natur..23..189.. doi:10.1038/023189a0. hdl:2027/uc1.$b71563. S2CID 43534483.

- Hume, A. O. (1879). Agricultural Reform in India. London, UK: W H Allen and Co.

- Wedderburn (1913):37

- Wedderburn (1913):35–38

- Moulton, Edward C. (1985). "Allan O. Hume and the Indian National Congress, a reassessment". Journal of South Asian Studies. 8 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1080/00856408508723063.

- Sitaramayya, B. Pattabhi (1935). The history of the Indian National Congress (1885–1935). Working Committee of the Congress. pp. 12–13.

- "[Miscellanea]". Pall Mall Gazette. 1 April 1890. p. 6 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Marriages". Dundee Advertiser. 2 February 1882. p. 8 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Howe, Ellic. Fringe Masonry in England, 1870–1885. Holmes Publishing Group.

- Blavatsky, H.P. (1968). Collected Writings. Volume 3. Blavatsky Writings Publication Fund. p. xxvii.

- Wedderburn (1913):134

- "Birds of South and East of Asia". The Cyclopaedia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, Commercial, Industrial and Scientific. Volume 1 (2 ed.). Scottish and Adelphi Press. 1871. p. 442.

- Buck, Edward J. (1904). Simla. Past and Present. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink and Co. pp. 116–117.

- Hume, A.O. (1876). "The Laccadives and the west coast". Stray Feathers. 4: 413–483.

- Taylor, A. Dundas (1876). "Southern India and Laccadive Islands (I.G.S. Clyde, 300 tons, 60 H.P.)". General Report of the operations of the Marine Survey of India, from the commencement in 1874, to the end of the official year 1875–76. Calcutta: Government of India. pp. 7, 16–17.

- Hume, A.O. (1881). "Novelties. Perdicula manipurensis, Sp. Nov". Stray Feathers. 9 (5&6): 467–471.

- St. John, O.B. (1889). "On the birds of southern Afghanistan and Kelat". Ibis. 6. 31 (2): 145–180. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1889.tb06382.x.

- Grote, A. (1875). "Catalogue of Mammals and Birds of Burma". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal: ix.

- "[Minutes of the Monthly General Meeting held on 7 January 1891]". Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal: 1. 1891.

- Anonymous (1905). "One hundred and seventeenth session, 1904–1905. November 3rd, 1904". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London: 1.

- BDJ (1913). "Obituary notices". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London: 60–61.

- Anon. (1885). "The Hume Collection of Indian Birds". Ibis. 3 (4): 456–462. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1885.tb06259.x.

- Thomas, Oldfied (1885). "On the mammals presented by Allan O. Hume, Esq., C.B., to the Natural History Museum". Proceedings of the General Meetings for Scientific Business of the Zoological Society of London. Zoological Society of London: 54–79.

- Prain, David (1890). "A List of Laccadive plants". Scientific Memoirs by Medical Officers of the Army of India: 47–69.

- Ripley, S. Dillon (1961). A Synopsis of the Birds of India and Pakistan. Bombay, UK: Bombay Natural History Society.

- Haffer, J. (1992). "The history of species concepts and species limits in ornithology". Bull. B.O.C. Centenary Supplement. 112A: 107–158.

- Hume, A. O. (1875). "What is a species?". Stray Feathers. 3: 257–262.

- Hume, A. O. (1869). "Letters, Announcements, &c". Ibis. 2 (5): 355–357. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1869.tb06888.x.

- Bensch, S.; Pearson, D. (2002). "The Large-billed Reed Warbler Acrocephalus orinus revisited" (PDF). Ibis. 144 (2): 259–267. doi:10.1046/j.1474-919x.2002.00036.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2007.

- Koblik, E. A.; Red'kin, Y. A.; Meer, M. S.; Derelle, R.; Golenkina, S. A.; Kondrashov, F. A.; Arkhipov, V. Y. (2011). "Acrocephalus orinus: A Case of Mistaken Identity". PLOS ONE. 6 (4): e17716. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617716K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017716. PMC 3081296. PMID 21526114.

- Kvartalnov, P. V.; Samotskaya, V. V.; Abdulnazarov, A. G. (2011). "From museum collections to live birds". Priroda (12): 56–58.

- Hume, A. O. (1896). My scrap book: or rough notes on Indian zoology and ornithology. Baptist Mission Press, Calcutta.

- Hume, Allan O. (1870). "Observations on some species of Indian birds, lately published in the Society's Journal". Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal: 85–86, 265–266.

- Hume, A. O. (1874). "[Editorial]". Stray Feathers. 2: 2.

- Oldham, T. (1873). "President's Address". Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal: 55–56.

- Hume, A. O. (1874). "Die Papageien". Stray Feathers. 2: 1–28.

- Hume, A. O. (1874). "Viscount Walden, president of the Zoological Society, on the editor of "Stray Feathers"". Stray Feathers. 2: 533–535.

- Bruce, Murray (2003). "Foreword: A brief history of classifying birds". The Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 8. Lynx Edicions. pp. 1–43.

- Wedderburn (1913):116.

- Lydekker, R. (1879). "Elementary sketch of the osteology of birds". Stray Feathers. 8 (1): 1–36.

- "Influence of rainfall on distribution of species". Stray Feathers. 7: 501–502. 1878.

- Sharpe, Bowdler (1893). "On the zoo-geographical areas of the world, illustrating the distribution of birds". Natural Science. 3: 100–108.

- Hume, A. O. (1887). "On the flight of birds". Stray Feathers. 10: 248–254.

- Hankin, E. H. (1914). Animal Flight: A Record of Observation. Iliffe and Sons, London. pp. 10–11.

- Shyamal, L. (2007). "Opinion: Taking Indian ornithology into the Information Age". Indian Birds. 3 (4): 122–137.

- Murray, James A. (1888). The avifauna of British India and its dependencies. Volume 1. Truebner, London. p. xiv.

- Warr, F. E. (1996). Manuscripts and Drawings in the ornithology and Rothschild libraries of The Natural History Museum at Tring. British Ornithologists' Club.

- "University and City Intelligence". Oxford Journal. 10 February 1877. p. 5 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Butler, AL (1899). "The birds of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Part 1". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 12 (2): 386–403.

- Shelley, G.E. (1880). A monograph of the Nectariniidae, or family of sun-birds. London: Self published. p. x.

- Hume, A. (1874). The Indian Ornithological Collector's Vade Mecum: containing brief practical instructions for collecting, preserving, packing and keeping specimens of birds, eggs, nests, feathers, and skeleton. Calcutta Central Press, Calcutta and Bernard Quaritch, London.

- Hume, A.O. (1889). The Nests and Eggs of Indian Birds. Volume 1 (2 ed.). London: R.H.Porter. p. 199.

- Hume, A.O. (1889). The Nests and Eggs of Indian Birds. Volume 1 (2 ed.). London: R.H.Porter. p. 378.

- Brooks, W. E. (1878). "On an overlooked species of (Reguloides)". Stray Feathers. 7 (1–2): 128–136.

- Wood-Mason, James (1874). "On a new Genus and Species (Hylæocarcinus Humei) of land-crabs from the Nicobar Islands". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 14 (81): 187–191. doi:10.1080/00222937408680954.

- Lydekker (1913):6–7

- Fedosenko, AK; DA Blank (2005). "Ovis ammon" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 773: 1–15. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2005)773[0001:oa]2.0.co;2.

- "India [From the Bombay Gazette of March 20]". Morning Post. 8 April 1880. p. 3 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Barker, A.T., ed. (1923). The Mahatma Letters. London, UK: T. Fisher Unwin.

- Oddie, Geoffrey (2013). Religious Conversion Movements in South Asia: Continuities and Change, 1800–1990. Routledge. p. 140.