Indian Civil Service

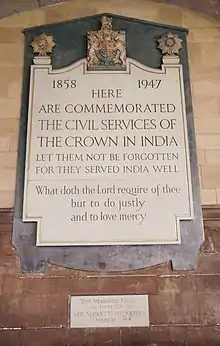

The Indian Civil Service (ICS), for part of the 19th century officially known as the Imperial Civil Service, was the elite higher civil service of the British Empire in British India during British rule in the period between 1858 and 1947.

Its members ruled over more than 200 million people[1] in the British Raj. They were ultimately responsible for overseeing all government activity in the 250 districts that comprised British India. They were appointed under Section XXXII(32) of the Government of India Act 1858,[2][3] enacted by the British Parliament.[4] The ICS was headed by the Secretary of State for India, a member of the British cabinet. At first almost all the top thousand members of the ICS, known as "Civilians", were British, and had been educated in the "best" British schools. By 1905, five per cent were from Bengal. In 1947 there were 322 Indians and 688 British members; most of the latter left at the time of partition and independence.[5]

Until the 1930s the Indians in the service were very few and not a single Indian was allowed to occupy a high-ranked post.[6] British historian Martin Wainwright notes that by the mid-1880s, "the basis of racial discrimination in the sub-continent had solidified".[7]

At the time of the creation of India and Pakistan in 1947, the outgoing Government of India's ICS was divided between India and Pakistan.[lower-alpha 1] Although these are now organised differently, the contemporary Civil Services of India, the Central Superior Services of Pakistan, Bangladesh Civil Service and Myanmar Civil Service are all descended from the old Indian Civil Service. Historians often rate the ICS, together with the railway system, the legal system, and the Indian Army, as among the most important legacies of British rule in India.[8]

Civil service

Origins and history

From 1858, after the demise of the East India Company's rule in India, the British civil service took on its administrative responsibilities. The change in governance came about due to the Indian Rebellion of 1857, which came close to toppling British rule in the country.[9]

Entry and setting

Up to 1853, the Directors of the East India Company made appointments of covenanted civil servants by nominations. This nomination system was abolished by the British Parliament in 1853 and it was decided that the induction would be through competitive examinations of all British subjects, without distinction of race.

The examination for admission to the service was first held only in London in the month of August of each year.[lower-alpha 2] All candidate also had to pass a compulsory horse-riding test.

An appointment to the civil service of the Company will not be a matter of favour but a matter of right. He who obtains such an appointment will owe it solely to his own abilities and industry. It is undoubtedly desirable that the civil servants of the Company should have received the best, the most finished education that the native country affords (the Report insisted that the civil servants of the Company should have taken the first degree in arts at Oxford or Cambridge Universities).

— Macaulay Committee Report[10]

The competitive examination for entry to the civil service was combined for the Diplomatic, the Home, the Indian, and the Colonial Services. Candidates had to be aged between 18 and 23 for appearing in the exam.[11] The total marks possible in the examination were 1,900 and one could get up to three chances for entry. Successful candidates underwent one or two years probation in the United Kingdom, according to whether they had taken the London or the Indian examination. This period[12] was spent at the University of Oxford (Indian Institute), the University of Cambridge, colleges in the University of London (including School of Oriental Studies) or Trinity College Dublin,[12] where a candidate studied the law and institutions of India, including criminal law and the law of evidence, which together gave knowledge of the revenue system, as well as reading Indian history and learning the language of the province to which they had been assigned.[12]

The Early Nationalists,[13] also known as the Moderates,[14] worked for several implementation of various social reforms such as the appointment of a Public Service Commission and a resolution of the House of Commons (1893) allowing for simultaneous examination for the Indian Civil Service in London and India.

By 1920, there were five methods of entry into the higher civil service: firstly, the open competitive examinations in London; secondly, separate competitive examinations in India; thirdly, nomination in India to satisfy provincial and communal representation; fourthly, promotion from the Provincial Civil Service and lastly, appointments from the bar (one-fourth of the posts in the ICS were to be filled from the bar).[15]

Uniform and dressing

Queen Victoria had suggested that the civil servants in India should have an official dress uniform, as did their counterparts in the Colonial Service. However, the Council of India decided that prescribing a dress uniform would be an undue expense for their officials.[16]

Although no uniform was prescribed for the Indian Civil Service until the early twentieth century. The only civilians allowed a dress uniform by regulations were those who had distinct duties of a political kind to perform, and who are thereby brought into frequent and direct personal intercourse with native princes.[16]

This uniform included a blue coat with gold embroidery, a black velvet lining, collar and cuffs, blue cloth trousers with gold and lace two inches wide, a beaver cocked hat with black silk cockade and ostrich feathers, and a sword.[16]

Nature and role

The civil services were divided into two categories – covenanted and uncovenanted. The covenanted civil service consisted of British civil servants occupying the higher posts in the government. The uncovenanted civil service was introduced to facilitate the entry of Indians at the lower rung of the administration.[17][18]

Salary and posts

After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the pay scales were drawn up.[1] Assistant Commissioners started out in their early twenties on around £300 a year.[1] The governorship of a British province was the highest post an ICS officer could aspire for.[19] The Governors at the top of the pyramid got £6,000 and allowances.[1] All ICS officers retired on the same pension £1,000.[1] In the first decades of the twentieth century, the imbalance in salaries and emoluments was so great that 8,000 British officers earned £13,930,554, while 130,000 Indians in government service were collectively paid a total of £3,284,163.[20]

They served a minimum of twenty five and a maximum of thirty five years service.[1]

ICS officers served as political officers in the Indian Political Department and also were given fifty percent judgeship in the state high court and rest were generally elevated from the high court bar.[19] The tenure of ICS officers serving as judges of the high court and Supreme Court was determined by the retirement age fixed for judges.[19]

Ranks/posts of the Indian (Imperial) Civil Service

Source:[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 4]

- Central Government

- Secretary to Government of India

- Joint Secretary to Government of India

- Deputy Secretary

- Additional Deputy Secretary

- Under Secretary

- Assistant Secretary to Government of India

- Courts

- Judge of State High Court

- District Judge

- State Government

- Chief Secretary (British Empire)

- Secretary to State Government

- Divisional Commissioner

- Deputy Commissioner / District Collector

Changes after 1912

If a responsible government is to be established in India, there will be a far greater need than is even dreamt of at present for persons to take part in public affairs in the legislative assemblies and elsewhere and for this reason the more Indians we can employ in the public service the better. Moreover, it would lessen the burden of Imperial responsibilities if a body of capable Indian administrators could be produced..

With the passing of the Government of India Act 1909, the Imperial Services headed by the Secretary of State for India, were split into two – All India Services and Central Services.[22]

Prior to the First World War, 95% of ICS officers were Europeans; after the war, the British government faced growing difficulties in recruiting British candidates to the service. Fewer and fewer young men in Britain were interested in joining, mainly due to the decreased levels of compensation to be had compared to other careers.[23] Confronted with numerous vacancies, the government resorted to direct appointments; between 1915 and 1924, 80% of new British ICS candidates entered the service in this way. During the same period, 44% of new appointments to the ICS were filled by Indians.[23]

In 1922, Indian candidates were permitted to sit the ICS examinations in Delhi; in 1924, the Lee Commission, chaired by Arthur Lee, 1st Viscount Lee of Fareham (which eventually led to the foundation of the Federal Public Service Commission and Provincial Public Service Commission under the Government of India Act 1935) made several recommendations: ICS officers should receive increased and more comprehensive levels of compensation, future batches of ICS officers should be composed of 40% Europeans and 40% Indians, with the remaining 20% of appointments to be filled by direct promotion of Indians from the Provincial Civil Services (PCS) and the examinations in Delhi and London were to produce an equal number of ICS probationers.[23] In addition, under-representation of candidates from Indian minority groups (Muslims, Burmese and so on) would be corrected by direct appointments of qualified candidates from those groups, while British candidates would continue to have priority over Indians for ICS appointments.[23] While initially successful, the expansion of the Indian independence movement from the late 1920s resulted in a hardening of Indian attitudes against European officers, and furthered distrust of Indian ICS appointments amongst Indians. This resulted in a declining recruitment base in terms of quality and quantity.[23]

The All India and class 1 Central Services were designated as Central Superior Services as early as 1924.[24] From 1924 to 1934, Administration in India consisted of "ten"[24] All India Services and five central departments, all under the control of Secretary of State for India, and 3 central departments under joint Provincial and Imperial Control.

From the 1935 Government of India act to Independence

The finances of India under British rule depended largely on land taxes, and these became problematic in the 1930s. Epstein argues that after 1919 it became harder and harder to collect the land revenue. The suppression of civil disobedience by the British after 1934 temporarily increased the power of the revenue agents, but after 1937 they were forced by the new Congress-controlled provincial governments to hand back confiscated land. The outbreak of the Second World War strengthened them again, but in the face of the Quit India movement the revenue collectors had to rely on military force, and by 1946–47 direct British control was rapidly disappearing in much of the countryside.[25]

The outbreak of war in 1939 had immediate consequences for recruitment to the ICS. The examinations in London were suspended after that year's batch (12 British and eight Indian examinees) had qualified. In 1940 and 1941, 12 and four British candidates, respectively, were nominated to the ICS; the following year, the final London-nominated ICS candidates, both of whom were Indian, entered the service. Examinations continued to be held in Delhi for Indian candidates until 1943, when the last seven ICS officers (seven examinees, two nominated) joined. By this time, the British government felt it could no longer rely unambiguously on the complete loyalty of its Indian officers. During the period of the Interim Government of India (1946-1947), a few British candidates were given emergency appointments in the ICS, though ultimately none of them ever served in India.[23]

Independence of India

At the time of the partition of India and departure of the British, in 1947, the Indian Civil Service was divided between the new Dominions of India and Pakistan. The part which went to India was named the Indian Administrative Service (IAS), while the part that went to Pakistan was named the "Civil Service of Pakistan" (CSP). In 1947, there were 980 ICS officers. 468 were Europeans, 352 Hindus, 101 Muslims, two depressed classes/Scheduled Castes, five domiciled Europeans and Anglo-Indians, 25 Indian Christians, 13 Parsis, 10 Sikhs and four other communities.[19] Most European officers left India at Partition, while many Hindus and Muslims went to India and Pakistan respectively. This sudden loss of officer cadre caused major challenges in administering the nascent states.

Despite offers from the new Indian and Pakistani governments, virtually all of the European former ICS officers left following partition, with the majority of those who did not opt for retirement continuing their careers either in the British Home Civil Service or in another British colonial civil service.[26] A few British ex-ICS officers stayed on over the ensuing quarter-century, notably those who had selected the "judicial side" of the ICS. The last British former ICS officer from the "judicial side" still serving in the subcontinent, Justice Donald Falshaw (ICS 1928), retired as Chief Justice of the Punjab High Court (now the Punjab and Haryana High Court) in May 1966,[27][28] receiving a knighthood in the British 1967 New Year Honours upon his return to Britain. J. P. L. Gwynn (ICS 1939), the last former ICS officer holding British nationality and the last to serve in an executive capacity under the Indian government, ended his Indian service in 1968 as Second Member of the Board of Revenue, but continued to serve in the British Civil Service until his final retirement in 1976.[29][30]

Justice William Broome (ICS 1932), a district and sessions judge at the time of Independence in 1947, remained in Indian government service as a judge. Having married an Indian, Swarup Kumari Gaur, in 1937, with whom he raised a family, he eventually renounced his British citizenship in 1958 and became an Indian citizen with the personal intervention of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, himself a former barrister who regarded Broome as a distinguished jurist and as "much as Indian as anybody can be who is not born in India". Upon his retirement on 18 March 1972 from the Allahabad High Court as its seniormost puisne judge, Broome was the last former ICS officer of European origin serving in India.[28]

Nirmal Kumar Mukarji (ICS 1943), a member of the final batch recruited to the ICS and who retired as Cabinet Secretary in April 1980, was the last Indian administrative officer who had originally joined as an ICS.[19] The last former ICS officer to retire, Aftab Ghulam Nabi Kazi (also a member of the final ICS batch of 1943),[31] retired as Chairman of the Pakistan Board of Investment in 1994. V. K. Rao (ICS 1937), the last living ICS officer to have joined the service in a regular pre-war intake, died in 2018. He was a retired Chief Secretary of Andhra Pradesh and was the oldest former ICS officer on record at the time of his death. As of 2020, only one ICS officer remains alive- V.M.M. Nair (ICS 1942), who transferred to the Indian Political Service in 1946 and then to the Indian Foreign Service after Independence.

Support and criticism

If you take that steel frame out of the fabric, it would collapse. There is one institution we will not cripple, there is one institution we will not deprive of its functions or of its privileges; and that is the institution which built up the British Raj – the British Civil Service of India.

Dewey has commented that "in their heyday they [Indian Civil Service officers] were mostly run by Englishmen with a few notable sons of Hindus and even a fewer Muslims were the most powerful officials in the Empire, if not the world. A tiny cadre, a little over a thousand strong, ruled more than 300 million Indians. Each Civilian had an average 300,000 subjects, and each Civilian penetrated every corner of his subjects' lives, because the Indian Civil Service directed all the activities of the Anglo-Indian state."[33]

The ICS had responsibility for maintaining law and order, and often were at loggerheads with the independence activists during the Indian independence movement. Jawaharlal Nehru often ridiculed the ICS for its support of British policies. He noted that someone had once defined the Indian Civil Service, "with which we are unfortunately still afflicted in this country, as neither Indian, nor civil, nor a service".[34]

As Prime Minister, Nehru retained the organisation and its top people, albeit with a change of title to the "Indian Administrative Service". It continued its main roles. Nehru appointed long-time ICS officials Chintaman Deshmukh as his Finance Minister, and K. P. S. Menon as his Foreign Minister. Sardar Patel appreciated their role in keeping India united after Partition, and noted in Parliament that without them, the country would have collapsed.

References

- Dewey, Clive (July 1993). Anglo-Indian Attitudes: Mind of the Indian Civil Service. A&C Black, 1993. ISBN 978-0-8264-3254-4.

- "The Indian Civil Service". Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- "Administering India: The Indian Civil Service". Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- Blunt, (1937)

- Surjit Mansingh, The A to Z of India (2010), pp 288–90

- Michael J. Nojeim (2004). Gandhi and King: The Power of Nonviolent Resistance. Greenwood. p. 50. ISBN 9780275965747.

- A. Martin Wainwright (2008). 'The better class' of Indians: social rank, imperial identity, and South Asians in Britain, 1858–1914. Manchester U.P. ISBN 9780719076664.

- Ramesh Kumar Arora and Rajni Goyal, Indian public administration: institutions and issues (1995) p. 42; Ranbir Vohra, The making of India: a historical survey (2001) p 185

- Naithani, Sadhana (2006). In quest of Indian folktales: Pandit Ram Gharib Chaube and William Crooke. Indiana University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-253-34544-8.

- Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances (8 June 2011). "History of civil services in India and Reforms" (PDF). New Delhi: Government of India. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "Historical Perspective of The Indian Civil Services & The Union Public Service Commission". UPSC Pathshala. 11 June 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- "The Colonial Service Training Courses : Professionalizing the Colonial Service". Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- Ralhan, Om Prakash, ed. (1995). Encyclopedia of Political Parties – India – Pakistan – Bangladesh – National – Regional – Local. 23. Moderate phrase in India. New Dehli: Anmol Publications. pp. 29–36.

The phase from 1885 to 1905 is known as the period of the Early Nationalists.

- Porter, Robin J. (2001). "Imperial India, 1858–1914". Oxford History of the British Empire: The Nineteenth Century. pp. 345, 434.

- Ramesh Kumar Arora and Rajni Goyal, Indian public administration: Institutions and Issues (1995) p 43

- Cohn, Bernard S. (1996). Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00043-5.

- Meghna Sabharwal, Evan M. Berman "Public Administration in South Asia: India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan (Public Administration and Public Policy)" (2013)

- "Civil Service". The British Library. 8 June 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- "Archive: The men who ran the Raj". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 4 September 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- "The Un-Indian Civil Service". OPEN. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- P. N., Chopra (2003). A Comprehensive History of India, Volume 3. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-207-2506-5.

- Goel, S.L. (2008). Public Personnel Administration : Theory and Practice. Deep and Deep Publications, 2008. ISBN 978-81-7629-395-2.

- David C. Potter, "Manpower Shortage and the End of Colonialism: The Case of Indian Civil Service," Modern Asian Studies, (Jan 1973) 7#1 pp 47–73

- Maheshwari, Shriram (1992). Problems and Issues in Administrative Federalism. Allied Publishers. ISBN 978-81-7023-342-8.

- Simon Epstein, 'District Officers in Decline: The Erosion of British Authority in the Bombay Countryside, 1919 to 1947' in Modern Asian Studies, (May 1982) 16#3, pp 493–518

- Wilson, John (2016). The Chaos of Empire: the British Raj and the Conquest of India. New York: PublicAffairs. pp. 492–494. ISBN 978-1-61039-293-8.

- "Last Briton Leaves Indian Service". The Times. 12 May 1966.

- McDonald, Douglas (2015). "Becoming Indian: William Broome and Colonial Continuity in Post-Independence India". Indian Historical Review. 42 (2): 303–331. doi:10.1177/0376983615597167.

- P. M. Gwynn (17 November 1999). "Obituary: J. P. L. Gwynn". The Independent. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- K. S. S. Seshan (16 June 2016). "JPL Gwynn: Smitten by the land and language". The Hindu. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- The India Office and Burma Office List: 1947. Harrison & Sons, Ltd. 1947. p. 241.

- Bali, H.N (2013). One Who Forged India's Steel Frame. Boloji.

- Dewey, Clive (1993). Anglo-Indian attitudes: the mind of the Indian Civil Service. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-85285-097-5.

- Jawaharlal Nehru, Glimpses of world history: being further letters to his daughter (Lindsay Drummond Ltd., 1949), p. 94

Notes

- ICS members in Pakistan was originally administering equally both West Pakistan and East Pakistan. However Pakistan was split into two. West Pakistan is now renamed to Islamic Republic of Pakistan and East Pakistan is now renamed to People's Republic of Bangladesh.

- As per published records and book named "The India List and India Office List 1905" as published by India Office and India Office Records.

- As per published records and book named "The India List and India Office List 1905" as published by India Office and India Office Records.

- As per Warrant or Precedence of 1905.

Further reading

- Blunt, Edward. The I.C.S.: the Indian civil service (1937)

- Burra, Arudra. "The Indian Civil Service and the nationalist movement: neutrality, politics and continuity," Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, Nov 2010, 48#4 pp 404–432

- Dewey, Clive. Anglo-Indian attitudes: the mind of the Indian Civil Service (1993)

- Ewing, Ann. "Administering India: The Indian Civil Service," History Today, June 1982, 32#6 pp 43–48, covers 1858–1947

- Gilmour, David. The Ruling Caste: Imperial Lives in the Victorian Raj (2007) excerpt and text search

- Gould, William. "The Dual State: The Unruly 'Subordinate', Caste, Community and Civil Service Recruitment in North India, 1930–1955," Journal of Historical Sociology, Mar-June 2007, Vol. 20 Issue 1/2, pp 13–43

- Krishna, Anirudh. "Continuity and change: the Indian administrative service 30 years ago and today," Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, Nov 2010, 48#4 pp 433–444

- MacMillan, Margaret. Women of the Raj: The Mothers, Wives, and Daughters of the British Empire in India (2007)

- Masani, Zareer. Indian Tales of the Raj (1990), interviews with retired ICS officers about pre-1947 days

- Potter, David C. India's Political Administrators,1919–1983 (1987) 289pp; the standard scholarly history

- Potter, David C. "The Last of the Indian Civil Service," South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies (Apr 1979), Vol. 2 Issue 1/2, pp 19–29

- Potter, David C. "Manpower Shortage and the End of Colonialism: The Case of Indian Civil Service," Modern Asian Studies, (Jan 1973) 7#1 pp 47–73 in JSTOR

- Sharma, Malti. Indianization of the civil services in British India, 1858–1935 (2001)

- Smith, Vincent Arthur (1903). (1 ed.). Dublin: Hodges, Figgis, & Co., Ltd.

- Thakur, R.N. The All India services: a study of their origin & growth (1969)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Indian Civil Service. |

.JPG.webp)