Alpine chough

The Alpine chough (/ˈtʃʌf/), or yellow-billed chough (Pyrrhocorax graculus), is a bird in the crow family, one of only two species in the genus Pyrrhocorax. Its two subspecies breed in high mountains from Spain eastwards through southern Europe and North Africa to Central Asia and Nepal, and it may nest at a higher altitude than any other bird. The eggs have adaptations to the thin atmosphere that improve oxygen take-up and reduce water loss.

| Alpine chough | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult of nominate subspecies in Switzerland | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Corvidae |

| Genus: | Pyrrhocorax |

| Species: | P. graculus |

| Binomial name | |

| Pyrrhocorax graculus (Linnaeus, 1766) | |

| |

| Approximate distribution shown in green | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Corvus graculus Linnaeus, 1766 | |

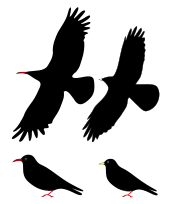

This bird has glossy black plumage, a yellow beak, red legs, and distinctive calls. It has a buoyant acrobatic flight with widely spread flight feathers. The Alpine chough pairs for life and displays fidelity to its breeding site, which is usually a cave or crevice in a cliff face. It builds a lined stick nest and lays three to five brown-blotched whitish eggs. It feeds, usually in flocks, on short grazed grassland, taking mainly invertebrate prey in summer and fruit in winter; it will readily approach tourist sites to find supplementary food.

Although it is subject to predation and parasitism, and changes in agricultural practices have caused local population declines, this widespread and abundant species is not threatened globally. Climate change may present a long-term threat, by shifting the necessary Alpine habitat to higher altitudes.

Taxonomy

_-_les_Arcs_2018.jpg.webp)

The Alpine chough was first described as Corvus graculus by Linnaeus in the Systema Naturae in 1766.[2] It was moved to its current genus, Pyrrhocorax, by English ornithologist Marmaduke Tunstall in his 1771 Ornithologia Britannica,[3] along with the only other member of the genus, the red-billed chough, P. pyrrhocorax.[4] The closest relatives of the choughs were formerly thought to be the typical crows, Corvus, especially the jackdaws in the subgenus Coloeus,[5] but DNA and cytochrome b analysis shows that the genus Pyrrhocorax, along with the ratchet-tailed treepie (genus Temnurus), diverged early from the rest of the Corvidae.[6]

The genus name is derived from Greek πύρρος (purrhos), "flame-coloured", and κόραξ (korax), "raven".[7] The species epithet graculus is Latin for a jackdaw.[8] The current binomial name of the Alpine chough was formerly sometimes applied to the red-billed chough.[9][10] The English word "chough" was originally an alternative onomatopoeic name for the jackdaw, Corvus monedula, based on its call. The red-billed chough, formerly particularly common in Cornwall and known initially as the "Cornish chough", eventually became just "chough", the name transferring from one genus to another.[11]

The Alpine chough has two extant subspecies.

- P. g. graculus, the nominate subspecies in Europe, north Africa, Turkey, the Caucasus and northern Iran.[4]

- P. g. digitatus, described by the German naturalists Wilhelm Hemprich and Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg as P. alpinus var. digitatus in 1833,[12] is larger and has stronger feet than the nominate race.[4] It breeds in the rest of the depicted Asian range, mainly in the Himalayas.[13]

Moravian palaeontologist Ferdinand Stoliczka separated the Himalayan population as a third subspecies, P. g. forsythi,[14] but this has not been widely accepted and is usually treated as synonymous with digitatus.[15][16] A Pleistocene form from Europe was similar to the extant subspecies, and is sometimes categorised as P. g. vetus.[17][18][19]

The Australian white-winged chough, Corcorax melanorhamphos, despite its similar bill shape and black plumage, is only distantly related to the true choughs.[20]

Description

The adult of the nominate subspecies of the Alpine chough has glossy black plumage, a short yellow bill, dark brown irises, and red legs.[4] It is slightly smaller than red-billed chough, at 37–39 centimetres (15–15 inches) length with a 12–14 cm (4.7–5.5 in) tail and a 75–85 cm (30–33 in) wingspan, but has a proportionally longer tail and shorter wings than its relative. It has a similar buoyant and easy flight.[13] The sexes are identical in appearance although the male averages slightly larger than the female. The juvenile is duller than the adult with a dull yellow bill and brownish legs.[4] The Alpine chough is unlikely to be confused with any other species; although the jackdaw and red-billed chough share its range, the jackdaw is smaller and has unglossed grey plumage, and the red-billed chough has a long red bill.[13]

The subspecies P. g. digitatus averages slightly larger than the nominate form, weighing 191–244 g (6.7–8.6 oz) against 188–252 g (6.6–8.9 oz) for P. g. graculus, and it has stronger feet.[4][13] This is in accordance with Bergmann's rule, which predicts that the largest birds should be found higher elevations or in colder and more arid regions. The extremities of the body, the bill and tarsus, were longer in warmer areas, in line with Allen's rule. Temperature seemed to be the most important cause of body variation in the Alpine chough.[21]

The flight of the Alpine chough is swift and acrobatic with loose deep wing beats. Its high manoeuvrability is accomplished by fanning the tail, folding its wings, and soaring in the updraughts at cliff faces. Even in flight, it can be distinguished from the red-billed chough by its less rectangular wings, and longer, less square-ended tail.[13][22]

The rippling preep and whistled sweeeooo calls of the Alpine chough are quite different from the more typically crow-like chee-ow vocalisations of the jackdaw and the red-billed chough. It also has a rolling churr alarm call, and a variety of quiet warbles and squeaks given by resting or feeding birds.[4] In a study of chough calls throughout the Palearctic region it was found that call frequencies in the Alpine chough showed an inverse relationship between body size and frequency, being higher-pitched in smaller-bodied populations.[23]

Distribution and habitat

The Alpine Chough breeds in mountains from Spain eastwards through southern Europe and the Alps across Central Asia and the Himalayas to western China. There are also populations in Morocco, Corsica and Crete. It is a non-migratory resident throughout its range, although Moroccan birds have established a small colony near Málaga in southern Spain, and wanderers have reached Czechoslovakia, Gibraltar, Hungary and Cyprus.[4]

This is a high-altitude species normally breeding between 1,260–2,880 metres (4,130–9,450 ft) in Europe, 2,880–3,900 m (9,450–12,800 ft) in Morocco, and 3,500–5,000 m (11,500–16,400 ft) in the Himalayas.[4] It has nested at 6,500 m (21,300 ft), higher than any other bird species,[24] even surpassing the red-billed chough which has a diet less well adapted to the highest altitudes.[25] It has been observed following mountaineers ascending Mount Everest at an altitude of 8,200 m (26,900 ft).[26] It usually nests in cavities and fissures on inaccessible rock faces, although locally it will use holes between rocks in fields,[27] and forages in open habitats such as alpine meadows and scree slopes to the tree line or lower, and in winter will often congregate around human settlements, ski resorts, hotels and other tourist facilities.[13] Its penchant for waiting by hotel windows for food is popular with tourists, but less so with hotel owners.[5]

Behaviour and ecology

Breeding

The Alpine chough is socially monogamous, showing high partner fidelity in summer and winter and from year to year.[28] Nesting typically starts in early May, and is non-colonial, although in suitable habitat several pairs may nest in close proximity.[4] The bulky nests are composed of roots, sticks and plant stems lined with grass, fine twiglets or hair, and may be constructed on ledges, in a cave or similar fissure in a cliff face, or in an abandoned building. The clutch is 3–5 glossy whitish eggs, averaging 33.9 by 24.9 millimetres (1.33 in × 0.98 in) in size,[29] which are tinged with buff, cream or light-green and marked with small brown blotches;[4] they are incubated by the female for 14–21 days before hatching.[13] The chicks hatch with a dense covering of natal down, in contrast to those of the red-billed chough which are almost naked,[30] and fledge in a further 29–31 days from hatching.[13] The young birds are fed by both parents, and may also be fed by other adults when they have fledged and joined the flock.[4] Breeding is possible in the high mountains because chough eggs have relatively fewer pores than those of lowland species, and lose less water by evaporation at low atmospheric pressure.[31] The embryos of bird species that breed at high altitude also have haemoglobin with a genetically determined high affinity for oxygen.[32]

In the western Italian Alps, the Alpine chough nests in a greater variety of sites than red-billed chough, using natural cliffs, pot-holes and abandoned buildings, whereas the red-billed uses only natural cliffs (although it nests in old buildings elsewhere).[4][25][33] The Alpine chough lays its eggs about one month later than its relative, although breeding success and reproductive behaviour are similar. The similarities between the two species presumably arose because of the same strong environmental constraints on breeding behaviour.[25]

A study of three different European populations showed a mean clutch size of 3.6 eggs, producing 2.6 chicks, of which 1.9 fledged. Adult survival rate varied from 83 to 92%, with no significant difference detected between males and females. Survival of first-year birds was, at 77%, lower than that of adults. The availability or otherwise of human food supplied from tourist activities did not affect breeding success.[28]

Feeding

In the summer, the Alpine chough feeds mainly on invertebrates collected from pasture, such as beetles (Selatosomus aeneus and Otiorhynchus morio have been recorded from pellets), snails, grasshoppers, caterpillars and fly larvae.[5] The diet in autumn, winter and early spring becomes mainly fruit, including berries such as the European Hackberry (Celtis australis) and Sea-buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides),[5] rose hips, and domesticated crops such as apples, grapes and pears where available.[34] It has been observed eating flowers of Crocus vernus albiflorus, including the pistils, perhaps as a source of carotenoids.[35] The chough will readily supplement its winter diet with food provided by tourist activities in mountain regions, including ski resorts, refuse dumps and picnic areas. Where additional food is available, winter flocks are larger and contain a high proportion of immature birds. The young birds principally frequent the sites with the greatest food availability, such as refuse dumps.[36] Both chough species will hide food in cracks and fissures, concealing the cache with a few pebbles.[37]

This bird always forages in groups, which are larger in winter than summer, and have constant composition in each season. Where food resources are restricted, adults dominate young birds, and males outrank females.[28] Foraging areas change altitudinally through the year, depending on climatic factors, food availability and food quality. During the breeding season, birds remain above the tree line, although they may use food provided by tourists at refuges and picnic areas.[34]

Movement to lower levels begins after the first snowfalls, and feeding by day is mainly in or near valley bottoms when the snow cover deepens, although the birds return to the mountains to roost. In March and April the choughs frequent villages at valley tops or forage in snow-free patches prior to their return to the high meadows.[34] Feeding trips may cover 20 km (12 mi) distance and 1,600 m (5,200 ft) in altitude. In the Alps, the development of skiing above 3,000 m (9,800 ft) has enabled more birds to remain at high levels in winter.[13]

Where their ranges overlap, the two chough species may feed together in the summer, although there is only limited competition for food. An Italian study showed that the vegetable part of the winter diet for the red-billed chough was almost exclusively Gagea bulbs dug from the ground, whilst the Alpine chough took berries and hips. In June, red-billed choughs fed mainly on caterpillars whereas Alpine choughs ate crane fly pupae. Later in the summer, the Alpine chough consumed large numbers of grasshoppers, while the red-billed chough added cranefly pupae, fly larvae and beetles to its diet.[25] In the eastern Himalayas in November, Alpine choughs occur mainly in juniper forests where they feed on juniper berries, differing ecologically from the red-billed choughs in the same region and at the same time of year, which feed by digging in the soil of terraced pastures of villages.[38]

Natural threats

Predators of the choughs include the peregrine falcon, golden eagle and Eurasian eagle-owl, while the common raven will take nestlings.[39][40][41][42] Alpine choughs have been observed diving at a Tibetan red fox. It seems likely that this "mobbing" behaviour may be play activity to give practice for when genuine defensive measures may be needed to protect eggs or young.[43]

The Alpine chough is a host of the widespread bird flea Ceratophyllus vagabunda, two specialist chough fleas Frontopsylla frontalis and F. laetus,[44] a cestode Choanotaenia pirinica,[45] and various species of chewing lice in the genera Brueelia, Menacanthus and Philopterus.[46]

Status

The Alpine chough has an extensive though sometimes fragmented range, estimated at 1–10 million square kilometres (0.4–3.8 million sq mi), and a large population, including an estimated 260,000 to 620,000 individuals in Europe. The Corsican population has been estimated to comprise about 2,500 birds.[47] Over its range as a whole, the species is not believed to approach the thresholds for the global population decline criteria of the IUCN Red List (i.e., declining more than 30% in ten years or three generations), and is therefore evaluated as Least Concern.[1]

At the greatest extent of the last glacial period around 18,000 years ago, southern Europe was characterised by cold open habitats, and the Alpine chough was found as far as south as southern Italy, well outside its current range.[48] Some of these peripheral prehistoric populations persisted until recently, only to disappear within the last couple of centuries. In the Polish Tatra Mountains, where a population had survived since the glacial period, it was not found as a breeding bird after the 19th century.[49] In Bulgaria, the number of breeding sites fell from 77 between 1950 and 1981 to just 14 in the 1996 to 2006 period, and the number of pairs in the remaining colonies were much smaller. The decline was thought to be due to the loss of former open grasslands which had reverted to scrubby vegetation once extensive cattle grazing ceased.[50] Foraging habitat can also be lost to human activities such as the construction of ski resorts and other tourist development on former alpine meadows.[51] Populations of choughs are stable or increasing in areas where traditional pastoral or other low intensity agriculture persists, but are declining or have become locally extinct where intensive farming methods have been introduced, such as Brittany, England, south-west Portugal and mainland Scotland.[52]

Choughs can be locally threatened by the accumulation of pesticides and heavy metals in the mountain soils, heavy rain, shooting and other human disturbances,[50] but a longer-term threat comes from global warming, which would cause the species' preferred Alpine climate zone to shift to higher, more restricted areas, or locally to disappear entirely.[53] Fossils of both chough species were found in the mountains of the Canary Islands. The local extinction of the Alpine chough and the reduced range of red-billed chough in the islands may have been due to climate change or human activity.[54]

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Pyrrhocorax graculus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012: e.T22705921A38351765. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T22705921A38351765.en.

- Linnaeus, C. (1766). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio duodecima (in Latin). Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 158.

- Tunstall, M. (1771). Ornithologia Britannica: seu Avium omnium Britannicarum tam terrestrium, quam aquaticarum catalogus, sermone Latino, Anglico et Gallico redditus (in Latin). London, J. Dixwell. p. 2.

- Madge, S.; Burn, Hilary (1994). Crows and jays: a guide to the crows, jays and magpies of the world. A & C Black. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-0-7136-3999-5.

- Goodwin, Derek; Gillmor, Robert (1976). Crows of the world. London: British Museum (Natural History). pp. 151–158. ISBN 978-0-565-00771-3.

- Ericson, Per G. P.; Jansén, Anna-Lee; Johansson, Ulf S.; Ekman, Jan (2005). "Inter-generic relationships of the crows, jays, magpies and allied groups (Aves: Corvidae) based on nucleotide sequence data" (PDF). Journal of Avian Biology. 36 (3): 222–234. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.493.5531. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2001.03409.x.

- "Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax [Linnaeus, 1758]". BTOWeb BirdFacts. British Trust for Ornithology. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- Woodhouse, Sidney Chawner (1982). The Englishman's pocket Latin-English and English-Latin dictionary. Taylor & Francis. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7100-9267-0.

- Lilford, Thomas Littleton Powys; Salvin, Osbert; Newton, Alfred; Thorburn, Archibald; Keulemans, Gerrard John (1897). Coloured figures of the birds of the British islands. 2. R. H. Porter. p. 56.

- Temminck, Coenraad Jacob (1815–40). Manuel d'ornithologie; Tableau systématique des oiseaux qui se trouvent en Europe. Paris: Sepps & Dufour. p. 122.

- Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 406–408. ISBN 978-0-7011-6907-7.

- Dickinson, E C; Dekker, R. W. R. J.; Eck, S.; Somadikarta S. (2004). [http://www.repository.naturalis.nl/document/43939</a> "Systematic notes on Asian birds. 45. Types of the Corvidae"]. Leiden Zoologische Verhandelingen. 350: 121.

- Snow, David; Perrins, Christopher M., eds. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic concise edition (2 volumes). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1464–1466. ISBN 978-0-19-854099-1.

- Stoliczka, Ferdinand (1874). "Letter to the Editor, 10 September 1873, Camp Leh". Stray Feathers: A Journal of Ornithology for India and Its Dependencies. 2 (4): 461–463.

- Vaurie, Charles (1954). "Systematic notes on Palearctic birds. No. 4, The choughs (Pyrrhocorax)". American Museum Novitates. 1658: 6–7. hdl:2246/3595.

- Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Anderton J. C. (2006). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. 2. Smithsonian Institution & Lynx Edicions. p. 598. ISBN 978-84-87334-67-2.

- (Hungarian with English abstract) Válóczi, Tibor (1999) "Vaskapu-barlang (Bükk-hegység) felső pleisztocén faunájának vizsgálata (Investigation of the Upper-Pleistocene fauna of Vaskapu-Cave (Bükk-mountain)). Folia historico naturalia musei Matraensis 23: 79–96

- Mlíkovský, Jirí (2002) Cenozoic birds of the world Archived 20 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine (Part 1: Europe). Ninox Press, Prague. ISBN 80-901105-3-8 p. 238

- Mourer-Chauviré, C.; Philippe, M.; Quinif, Y.; Chaline, J.; Debard, E.; Guérin, C.; Hugueney, M. (2003). "Position of the palaeontological site Aven I des Abîmes de La Fage, at Noailles (Corrèze, France), in the European Pleistocene chronology". Boreas. 32 (3): 521–531. doi:10.1080/03009480310003405.

- "ITIS Standard Report Page: Corcorax". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

- Laiolo, Paola; Rolando, Antonio (2000). "Ecogeographic correlates of morphometric variation in the Red-billed Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax and the Alpine Chough Pyrrhocorax graculus". Ibis. 43 (3): 602–616. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2001.tb04888.x.

- Burton, Robert (1985). Bird behaviour. London: Granada. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-246-12440-1.

- Laiolo, Paola; Rolando, Antonio; Delestrade, Anne; de Sanctis, Augusto (2001). "Geographical variation in the calls of the choughs". The Condor. 103 (2): 287–297. doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2001)103[0287:GVITCO]2.0.CO;2.

- Bahn, H.; Ab, A. (1974). "The avian egg: incubation time and water loss" (PDF). The Condor. 76 (2): 147–152. doi:10.2307/1366724. JSTOR 1366724.

- Rolando, Antonio; Laiolo, Paola (April 1997). "A comparative analysis of the diets of the chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax and the alpine chough Pyrrhocorax graculus coexisting in the Alps". Ibis. 139 (2): 388–395. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1997.tb04639.x.

- Silverstein Alvin; Silverstein, Virginia (2003). Nature's champions: the biggest, the fastest, the best. Courier Dover Publications. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-486-42888-8.

- Baumgart, W. (1967). "Alpendohlenkolonien in Felsschächten des Westbalkan". Journal für Ornithologie (in German). 108 (3): 341–345. doi:10.1007/BF01671883. S2CID 41532963.

- Delestrade, Anne; Stoyanov, Georgi (1995). "Breeding biology and survival of the Alpine Chough Pyrrhocorax graculus". Bird Study. 42 (3): 222–231. doi:10.1080/00063659509477171.

- Harrison, Colin James Oliver (1975). A field guide to the nests, eggs and nestlings of European birds: with North Africa and the Middle East. Collins. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-00-219249-1.

- Starck, J Matthias; Ricklefs, Robert E. (1948). Avian growth and development. Evolution within the altricial precocial spectrum (PDF). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-510608-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2008.

- Rahn, H.; Ar, A. (1974). "The avian egg: incubation time and water loss". The Condor. 76 (2): 147–152. doi:10.2307/1366724. JSTOR 1366724. S2CID 27372255.

- Black, Craig Patrick; Snyder, Gregory K (1980). "Oxygen transport in the avian egg at high altitude". American Zoologist. 20 (2): 461–468. doi:10.1093/icb/20.2.461.

- Blanco, Guillermo; Fargallo, Juan A.; Tella, José Luis Cuevas; Jesús A. (February–March 1997). "Role of buildings as nest-sites in the range expansion and conservation of choughs Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax in Spain" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 79 (2–3): 117–122. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(96)00118-8. hdl:10261/58104.

- Laiolo, Paola; Rolando, Antonio; Carisio, Lorendana (2001). "Winter movements of the Alpine Chough: implications for management in the Alps" (PDF). Journal of Mountain Ecology. 6: 21–30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2007.

- McKibbin, René; Bishop, Christine A. (2008). "Feeding observations of the western Yellow-breasted Chat in the south Okanagan valley British Columbia, Canada during a seven-year study period" (PDF). British Columbia Birds. 18: 24–25.

- Delestrade, Anne (1994). "Factors affecting flock size in the Alpine Chough Pyrrhocorax graculus". Ibis. 136: 91–96. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1994.tb08135.x.

- Wall, Stephen B. Vander (1990). Food hoarding in animals. University of Chicago Press. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-226-84735-1.

- Laiolo, Paola (2003). "Ecological and behavioural divergence by foraging Red-billed Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax and Alpine Choughs P. graculus in the Himalayas". Ardea. 91 (2): 273–277. (abstract)

- "A year in the life of Choughs". Birdwatch Ireland. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- "Know Your Crows". Operation Chough. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- Rolando, Antonio; Caldoni, Riccardo; De Sanctis, Augusto; Laiolo, Paola (2001). "Vigilance and neighbour distance in foraging flocks of red-billed choughs, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax". Journal of Zoology. 253 (2): 225–232. doi:10.1017/S095283690100019X.

- Blanco, Guillermo; Tella, José Luis (August 1997). "Protective association and breeding advantages of choughs nesting in lesser kestrel colonies". Animal Behaviour. 54 (2): 335–342. doi:10.1006/anbe.1996.0465. hdl:10261/58091. PMID 9268465. S2CID 38852266.

- Blumstein, Daniel T.; Foggin, J. Marc (March 1993). "Playing with fire? alpine choughs play with a Tibetan red fox". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 90: 513–515.

- Rothschild, Miriam; Clay, Theresa (1953). Fleas, flukes and cuckoos. A study of bird parasites. London: Collins. pp. 89, 95.

- (Russian) Georgiev B. B.; Kornyushin, VV.; Genov, T. (1987). "Choanotaenia pirinica sp. n. (Cestoda, Dilepididae), a parasite of Pyrrhocorax graculus in Bulgaria". Vestnik Zoologii. 3: 3–7.

- Kellogg, V. L.; Paine, J. H. (1914). "Mallophaga from birds (mostly Corvidae and Phasianidae) of India and neighbouring countries". Records of the Indian Museum. 10: 217–243. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.5626.

- Delestrade, A. (1993). "Statut, distribution et abondance du chocard à bec jaune Pyrrhocorax graculus en Corse" [Status, distribution and abundance of the Alpine Chough Pyrrhocorax graculus in Corsica, Mediterranean France]. Alauda (in French). 61 (1): 9–17. ISSN 0002-4619.

- Yalden, Derek; Albarella, Umberto (2009). The history of British birds. Oxford University Press. pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-0-19-921751-9.

- Tomek, Teresa; Bocheński, Zygmunt (2005). "Weichselian and Holocene bird remains from Komarowa Cave, Central Poland". Acta Zoologica Cracoviensia. 48A (1–2): 43–65. doi:10.3409/173491505783995743.

- Stoyanov, Georgi P.; Ivanova, Teodora; Petrov, Boyan P.; Gueorguieva, Antoaneta (2008). "Past and present breeding distribution of the alpine chough (Pyrrhocorax graculus) in western Stara Planina and western Predbalkan Mts. (Bulgaria)" (PDF). Acta Zoologica Bulgarica. Suppl. 2: 119–132.

- Rolando, Antonio; Patterson, Ian James (1993). "Range and movements of the Alpine Chough Pyrrhocorax graculus in relation to human developments in the Italian Alps in summer". Journal of Ornithology. 134 (3): 338–344. doi:10.1007/BF01640430. S2CID 21498755.

- Pain, Debbie; Dunn, Euan (1996). "The effects of agricultural intensification upon pastoral birds: lowland wet grasslands (The Netherlands) and transhumance (Spain)". Wader Study Group Bulletin. 81: 59–65.

- Sekercioglu, Cagan H; Schneider, Stephen H.; Fay, John P. Loarie; Scott R. (2008). "Climate change, elevational range shifts, and bird extinctions" (PDF). Conservation Biology. 22 (1): 140–150. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00852.x. PMID 18254859.

- Reyes, Juan Carlos Rando (2007). "New fossil records of choughs genus Pyrrhocorax in the Canary Islands: hypotheses to explain its extinction and current narrow distribution" (PDF). Ardeola. 54 (2): 185–195.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pyrrhocorax graculus (Alpine chough). |

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 0.86 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- Alpine chough videos, photos & sounds on the Internet Bird Collection