Ancient furniture

The furniture of the ancient world was made of many different materials. The materials included reeds, wood, stone, metals, straws, ivory. In Mesopotamia and Israel, furniture would be inlaid with metals. Furniture would have images carved in them. Such as mythological creatures or constellations. The chairs would be stylized with metals, finials, and inlays. The chairs could also have upholstery. Some chairs had legs shaped like animal legs. In Ancient Egypt chairs had legs shaped like animal legs and mortise and tenon joints. The Kline, a Greek table was made by placing a rectangular surface on three wooden legs. The Romans had chairs called Sella. Tables in Mesopotamia were decorated with metals and in Egypt they were round. The mensa and the abacus was a Roman table supported by three legs. Beds in Ancient India beds would be made by extending mats across a frame. Mushiro mats were Ancient Japanese mats made of straws. Ancient Japan also had grass blinds called Sudare, quilts called fusuma, canopies Shōjin, and shrines called butsudan. Lacquerware was common in Chinese furniture. Ivory carving were common in Ancient Israeli furniture. The ancient Aztecs grew crops in their own homes.

Mesopotamia

Most Mesopotamian furniture was constructed out of wood, reeds, and other biodegradable materials.[1] This means that there are few archaeological finds of ancient furniture from Mesopotamia. Much of the Mesopotamian furniture we have consists of artifacts the Assyrians gained found in their conquests. Mesopotamian furniture was similar to Ancient Egyptian furniture. Although Mesopotamian furniture was heavier, and had more curves then Egyptian furniture. Although these curves appeared more frequently.[2] Common furniture in Mesopotamia were beds, stools, and chairs both of which were made of palmwood or woven reeds. Chairs could be made from 17 different types of wood.[3] Wealthy citizens would have chairs padded with felt, rushes, or palm wood. The chairs would also have leather upholstery.[3] The most expensive chairs were inlaid with bronze, copper, silver, and gold. Oftentimes the chairs would have bronze panels that had images of griffins and winged deities carved into them. Chairs would also have wooden and ivory finials depicting arms. These finials would have bull's heads.[3]The chairs would be painted with many bright colors. People would also use wooden tables to hold meals or belongings. Rich people would often decorate their tables with metals. They would also have elaborately carved chests to hold their belongings in. Baskets made of reed and bins made of sun-dried clay, palmwood, or reeds were also items used to store belongings. Wealthy Mesopotamians had beds with wooden frames and mattresses stuffed with cloth, goat's hair, wool, or linen. Some ancient art depicts people lounging on sofas.[4] The legs of the sofas had iron panels depicting women and lions.[3] Bathrooms would have had bathtubs, stools, jars, mirrors, and large water pitchers occasionally with a pottery dipper. Mats were made from woven reeds.[5] People would light their houses by placing a wick made of reed or wool in sesame seed oil then lighting it.[3] Doors and doorframes might have been made of wood, on occasion doors would be made of red ox-hide. Mesopotamians would hide a crude statue in their house to ward off evil spirits.[3] Rich Sumerians would have toilets and proper drainage systems.[6][7] Cast-bronze and carved-bone finials would be applied to furniture. Furniture legs would be decorated with metal rings.[2] In Ancient Assyria plaques would be used as furniture. The Ancient Assyrians had carved ivory pieces. It was used to make fan handles, boxes, and furniture inlays. The furniture would commonly depict flowers.[8]

Egypt

Most Egyptian furniture was wooden, however, there was some stone furniture. The stone furniture usually had portraits of gods on them.[9] In Ancient Egypt chairs were used by both the poor and the rich. However, thrones were exclusively used by the wealthy. There are depictions of a low-back ox-legged chair. There is also a portrait of Amenhotep III sitting in a low-back lion legged chair. Most couches and chairs in Ancient Egypt and animal furniture. Some of the legs would be the front legs of the animal, while the others would be the back legs. Some furniture depicts events and people. One Ancient Egyptian chair archaeologists have discovered is known as the Anderson chair. On the back of the chair, there is an ornament that was made of alternating light and dark wood. There are also circular inlays on the back of the chair and bones on the top rail of the chair. The legs of the chair are carved to appear like a lion's legs. The feet of the Anderson chair is carved on horizontally lined spools. The chair was shaped to conform to the lumbar area in the back. The joints are mortised and have wide tenons that are fastened with pegs. Other Egyptian chairs were mortised into vertical side rails. The rails, alongside curved braces pegged into the chair, hold up the back of the Egyptian chair. The legs of Egyptian chairs are mortised into the rails. The rails are also mortised into each other. Some rails have 15 holes, others have 13.[10] In Ancient Egypt would also have stands, stools, couches, and beds. Ceremonial stools would be blocks of stone or wood. If the stool was made out of wood it would have a flint seat.[2] Tables were rare in ancient Egypt. The tables that did exist were round.[9][11] Ancient beds found in the tombs of Tutankhamen and Hetepheres would usually resemble that of an animal, usually a bull. The beds sloped up towards the head. To prevent the sleeper from falling off the bed, there was a wooden footboard. Wood or Ivory headrests were used instead of pillows. To upholster the beds leather and fabrics were used to support the mattress Egyptians would weave leather strips into the open holes of the bed frame. Royal beds would often be gilded and richly decorated.[11] Beds were constructed out of wood and had a simple framework that was supported by four legs. A plaited flax cord was lashed to the side of the framework. The flax cords were made by weaving together opposite sides of the framework to form an elastic surface for the user.[2] Tables usually had four legs, although some had three legs and one leg. They were used for games and dining. The game called Mehen would be played on a one legend table carved or inlaid into the shape of a snake. The Egyptians also had offering tables made of stone which would be placed in home shrines or tombs.[11] Footstools were made of wood. The Royal Footstool had enemies of Egypt painted on the footstool, so that way the pharaoh could symbolically crush them.[2][12]

Dilmun

There is no surviving furniture from Dilmun. The only records of furniture in Dilmun are seals found mainly in Bahrain and Failaka. On these seals, furniture is depicted from a side view. This forced historians to rely on the dimensions of other civilization's furniture so they could recreate what the furniture of Dilmun looked like. Chairs and thrones would have been built out of Shorea wood. Dowels would have been used for mortise and tenon joints. Sharp chisels would be used to carve hardwood into furniture. Turpentine was used to thin animal fat, wax, and honey to finish the wood. Horizontal stretchers. It is possible glue could have been used in the construction of furniture. Decorations for the furniture would have been borrowed from other civilizations. The seals depict thrones and chairs with stools in front of them. The people who would have used these thrones and chairs were kings, important officials, or wealthy people. Stools in Dilmun are well built and are similar to thrones. However, they have no back support. Stools would have been well decorated if they were used by gods, kings, officials, and rich people. One seal depicts a throne with vertical back support and front legs. Other seals depict a similar throne but with a rectangular frame base. In some seals, chairs are depicted with seats shaped like boxes. At the top of the back support of some chairs, there was a sphere with horns imitating a goat's or bull's head. Chairs had back fixed to the lower frame of the seat. These posts would penetrate the seat. The chairs would have been 90 cm high, the seat and the back support would have been 45 cm high or 17 inches high. The diameter of the back is 8 cm or 3 inches. The width of the seat is 70 cm (27 in), the depth of the seat is 50 cm (19 in). The legs were 5 cm by 5 cm (1 in by 1 in) or 10 cm by 5 cm (3 in by 1 in). Very few tables have been depicted in seals from Dilmun. All of these tables are ceremonial. Dilmunite tables had a concave or crescent top sitting on a column that divides into three curved legs with bull’s hooves. Such tables may have been used for trade. It is unknown what furniture Dilmunites would have used instead of tables. However, no beds or storage furniture has been depicted on these seals. A seal from Sar depicts a couple sharing beer through straws from a drinking vessel. The top of the vessel is crescent-shaped. Rectangular Hatched altars would be used for sacrificing items and animals to the Dilmunite gods. The tabletop of the altar is concave. Spikes would stick out of the column. The legs of the altar end in animal hooves. The column and legs may be one piece, with the concave top joining the piece. Some altars looked like double boxes. [11]

Greece

Ancient Greek furniture was typically constructed out of wood, though it might also be made of stone or metal, such as bronze, iron, gold, and silver. Little wood survives from ancient Greece, though varieties mentioned in texts concerning Greece and Rome include maple, oak, beech, yew, and willow.[13] Pieces were assembled using mortise-and-tenon joinery, held together with lashings, pegs, metal nails, and glue. Wood was shaped by carving, steam treatment, and the lathe, and furniture is known to have been decorated with ivory, tortoise shell, glass, gold, or other precious materials.[14] Similarly, furniture could be veneered with expensive types of wood to make the object appear more costly,[15] though classical furniture was often pared down in comparison to objects attested in the East, or those from earlier periods in Greece.[16]

Extensive research was done on the forms of Greek furniture by Gisela Richter, who utilized a typological approach based primarily on illustrated examples depicted in Greek art, and it is from Richter’s account that the main types can be delineated.[17]

Seating

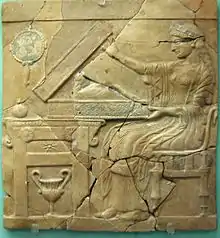

The modern word “throne” is derived from the ancient Greek thronos (Greek singular: θρόνος), which was a seat designated for deities or individuals of high status or honor.[18] The colossal chryselephantine statue of Zeus at Olympia, constructed by Phidias and lost in antiquity, featured the god Zeus seated on an elaborate throne, which was decorated with gold, precious stones, ebony, and ivory, according to Pausanias.[19] Less extravagant though more influential in later periods is the klismos (Greek singular: κλισμός), an elegant Greek chair with a curved backrest and legs whose form was copied by the Romans and is now part of the vocabulary of furniture design. A fine example is shown on the grave stele of Hegeso, dating to the late fifth century BCE.[20] As with earlier furniture from the east, the klismos and thronos could be accompanied by footstools.[21] There are three types of footstools outlined by Richter – those with plain straight legs, those with curved legs, and those shaped like boxes that would have sat directly on the ground.[22]

The most common form of Greek seat was the backless stool, which must have been found in every Greek home. These were known as diphroi (Greek singular: δίφρος) and they were easily portable.[23] The Parthenon frieze displays numerous examples, upon which the gods are seated.[24] Several fragments of a stool were discovered in the forth-century BCE. tomb in Thessaloniki, including two of the legs and four transverse stretchers. Once made of wood and covered in silver foil, all that remains of this piece are the parts made of precious metal.[25][26]

The folding stool, known as the diphros okladias (Greek singular: δίφρος ὀκλαδίας), was practical and portable. The Greek folding stool survives in numerous depictions, indicating its popularity in the Archaic and Classical periods; the type may have been derived from earlier Minoan and Mycenaean examples, which in turn were likely based on Egyptian models.[27] Greek folding stools might have plain straight legs or curved legs that typically ended in animal feet.[28]

Klinai

A couch or kline (Greek: κλίνη) was a form used in Greece as early as the late seventh century B.C.E.[29] The kline was rectangular and supported on four legs, two of which could be longer than the other, providing support for an armrest or headboard. Three types are distinguished by Richter – those with animal legs, those with “turned” legs, and those with “rectangular” legs, although this terminology is somewhat problematic.[30] The fabric would have been draped over the woven platform of the couch, and cushions would have been placed against the arm or headrest, making the Greek couch an item well suited for a symposium gathering. The foot of a bronze bed discovered in situ in the House of the Seals at Delos indicate how the “turned” legs of a kline might have appeared.[31] Numerous images of klinai are displayed on vases, topped by layers of intricately woven fabrics and pillows. These furnishings would have been made of leather, wool, or linen, though silk could also have been used. Stuffing for pillows, cushions, and beds could have been made of wool, feathers, leaves, or hay.[32]

Tables

In general, Greek tables (Greek singular: τράπεζα, τρἰπους, τετράπους, φάτνη, ὲλεóς) were low and often appear in depictions alongside klinai and could perhaps fit underneath.[33] The most common type of Greek table had a rectangular top supported on three legs, though numerous configurations exist. Tables could have circular tops, and four legs or even one central leg instead of three. Tables in ancient Greece were used mostly for dining purposes – in depictions of banquets, it appears as though each participant would have utilized a single table, rather than a collective use of a larger piece. On such occasions, tables would have been moved according to one's needs.[34]

Tables also would have figured prominently in religious contexts, as indicated in vase paintings. One example by the Chicago Painter from The Art Institute of Chicago, dating to around 450 B.C.E., shows an image of three women performing a Dionysian ritual, in which a table functions as an appropriate place to rest a kantharos – a wine vessel associated with Dionysus.[35] Other images indicate that tables could range in style from the highly ornate to the relatively unadorned.

Rome

To a large extent, the types and styles of ancient Roman furniture followed those of their Classical and Hellenistic Greek predecessors. Because of this, it is difficult to differentiate Roman forms from earlier Hellenistic ones in many cases. Gisela Richter’s typological approach is useful in tracing developments of Greek furniture into Roman expressions.[36] Knowledge of Roman furniture is derived mainly from depictions in frescoes and representations in sculpture, along with actual pieces of furniture, fragments, and fittings, several of which were preserved by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79. The most well-known archaeological sites with preserved images and fragments from the eruption are Pompeii and Herculaneum in Italy. There are fine examples of reconstructed Roman furniture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City as well as the Capitoline Museum in Rome.[37]

Chairs

The sella, or stool or chair, was the most common type of seating in the Roman period, probably because of its easy portability. Also, the sella in its simplest form was inexpensive to make. Both slaves and emperors used it, although those of the poor were surely plain, while the wealthy had access to precious woods, ornamented with inlay, metal fittings, ivory, and silver and gold leaf. Bronze sellae from Herculaneum were squares and had straight legs, decorative stretchers, and a dished seat.[38] The sella curulis, or folding stool, was an important indicator of power in the Roman period.[39] There were sellae resembling both stools and chairs that folded in a scissor fashion to facilitate transport.[40]

The Roman cathedra was a chair with a back, although there is disagreement as to the exact meaning of the Latin term. Richter defines the cathedra as a later version of the Greek klismos, which she says was never as popular as its Greek predecessor.[41] A. T. Croom, however, considers the cathedra to be a high-backed wickerwork chair that was typically associated with women. They have also been seen being used as early school teachers, pupils would sit around him in this chair while he taught. It showed who held the seat of power in the classroom.[42] As with Greek furniture, the names of various Roman types as found in texts cannot always be associated with known furniture forms with certainty.

The Latin solium is considered to be equivalent to the Greek term thronos and thus is often translated as “throne.”[43] These were like modern chairs, with backs and armrests. Three types of solia based on Greek prototypes are distinguished by Richter: thrones with “turned” and “rectangular” legs and grandiose thrones with solid sides, of which several examples remain in stone.[44] Also, a type with a high back and arms, resting upon a cylindrical or conical base, is said to derive from Etruscan prototypes.[45]

Couches

Few actual Roman couches survive, although sometimes the bronze fittings do, which help with the reconstruction of the original forms. While in wealthy households beds were used for sleeping in the bedrooms (lectus cubicularis), and couches for banqueting while reclining were used in the dining rooms (lectus tricliniaris), the less well off might use the same piece of furniture for both functions.[46] The two types might be used interchangeably even in richer households, and it is not always easy to differentiate between sleeping and dining furniture. The most common type of Roman bed took the form of a three-sided, open rectangular box, with the fourth (long) side of the bed open for access. While some beds were framed with boards, others had slanted structures at the ends, called fulcra, to better accommodate pillows. The fulcra of elaborate dining couches often had sumptuous decorative attachments featuring ivory, bronze, copper, gold, or silver ornamentation.[47]

The bench, or subsellium, was an elongated stool for two or more users. Benches were considered to be “seats of the humble,” and were used in peasant houses, farms, and bathhouses. However, they were also found in lecture halls, in the vestibules of temples, and served as the seats of senators and judges. Roman benches, like their Greek precedents, were practical for the seating of large groups of people and were common in theaters, amphitheaters, odeons and auctions.[48] The scamnum, related to the subsellium but smaller, was used as both a bench and a footstool.[49]

Tables

Types of Roman tables include the abacus and the mensa, which are distinguished from one another in Latin texts. The term abacus might be used for utilitarian tables, such as those for making shoes or kneading dough, as well as high-status tables, such as sideboards for the display of silver.[50] A low, three-legged table, thought to represent the mensa delphica, was often depicted next to reclining banqueters in Roman paintings. This table has a round tabletop supported by three legs configured like those of a tripod.[51] Several wooden tables of this type were recovered from Herculaneum.

Surviving examples

The most important source for wooden furniture of the Roman period is the collection of carbonized furniture from Herculaneum. While the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 C.E. was tremendously destructive to the region, the hot liquid lava that engulfed the town of Herculaneum ultimately preserved the wooden furniture, shelves, doors, and shutters in carbonized form.[52] Their preservation, however, is imperiled, as some of the pieces remain in situ in their houses and shops, encased in unprotected glass or entirely open and accessible. Upon excavation, much of the furniture was conserved with paraffin wax mixed with carbon powder, which coats the wood and obscures important details such as decorations and joinery. It is now impossible to remove the wax coating without further damaging the furniture. Several wooden pieces were found with bone and metal fittings.[53]

Wooden shelving and racks are found in shops and kitchens in the Vesuvian sites, and one house has elaborate wooden room dividers.

Greek bronze lampstand, 3rd century BC

Greek bronze lampstand, 3rd century BC Marble table from Pompeii

Marble table from Pompeii Bronze table from Pompeii

Bronze table from Pompeii Reconstructed living room

Reconstructed living room Table support from Roman Greece

Table support from Roman Greece.jpg.webp) Bench from the women's baths at Herculaneum

Bench from the women's baths at Herculaneum Racks for amphorae in a shop in Herculaneum

Racks for amphorae in a shop in Herculaneum House of the wooden partition (#8) in Herculaneum

House of the wooden partition (#8) in Herculaneum Mosaic of Two women making a call on a witch, from Pompeii

Mosaic of Two women making a call on a witch, from Pompeii Roman throne with solid sides

Roman throne with solid sides Diocletian's Mensa

Diocletian's Mensa

India

In Ancient India people used bamboo to create thrones. The colors of the bamboo ranged from yellow to black.[54] Shisham, Mango, and Teak wood were commonly used for furniture in Ancient India.[55] The lower classes of Ancient India had beds made of a mat extended across a small frame. Houses of the poor would also have basins, stone jar-stands, querns, palettes, flat dishes, a brass drinking vessel with a spout, a lamp, jars, mortar, pots, needles, awls, knives, saws, and axes. The needles and awls were made from ivory.[56]Chairs and bed stands would be made from wood. Stools would be made from wicker wood. They had mats made from reeds, lamps made from copper, clay, and shells[57]

Japan

In Ancient Japan bamboo was very rarely used in furniture.[54] In the earliest parts of Japanese history, during the Kōbun Period, people lived in pit-dwellings. These pit dwellings had straw-mats called mushiro, pitch pine lamps, oil lamps, baskets, and lacquerware. The beds in these houses were made from dirtand there were open-hearths.[58] Eventually, houses started to be built out of timber with its bark unshaven. Posts were planted in holes in the ground and gables were placed in the grass. These houses would have antechambers made for women. The antechamber was separated from the rest of the world by doors made of curtains and window blinds made of grass called Sudare. Beds would be made by stacking mushiro mats and then spreading the mats with a fusuma quilt. Above the bed was a canopy called a shōjin made of a wood-lath grid covered in mushiro mats. The canopy would catch dust. Later in Japanese history screens would become common furniture. The byobu is a multi-paneled screen covered in paintings. A screen covered by only one painting was called a tsuitate. In Japan chests were called tansu. Japanese households also had family shrines called the butsudan. Other than reading stands, writing stands, headrests, Kimono racks, and armrests, there was no other furniture in Japan. This was because Japanese people would often sit on the floor rather than tables or chairs. This practice was given to the Japanese by the Chinese. Other Asian cultures borrowed furniture from the Chinese, such as Korea. Most furniture would not be decorated unless it was lacquered.[59]

China

In the Ming dynasty of Ancient China bamboo was used to make furniture for use outside. Bamboo furniture mainly appeared in southern China. Furniture could also be made from dense hardwoods. Hardwood was valued for its grain patterns and its beauty. Later softwoods would also be used. Wealthy Chinese people would use lacquered wood, sometimes polychrome lacquered wood.[60] Most wooden furniture in Ancient China was lacquered. In both China and India bamboo furniture was produced through joinery.[54] Tables and desks were very low because oftentimes people would sit on the ground. Most furniture was below 50 cm or 19 inches. An ancient bed found in Xinjiang is supported by six feet and is painted with a cloud pattern. Mortise and tenon joints were very common in Chinese furniture. An ancient Chinese chest found in an ancient tomb was painted with mystical patterns and mythical beings such as the god Fuxi. The story of Houyi and a diagram of constellations were also carved on the chest. In Ancient China there was a type of chair called a huchaung.[61] The huchaung was a consolable folding chair. People would often use beds as dining tables. Rich people would often decorate their beds with screens, curtains, and maybe jewelry to show off their wealth. Couches were smaller than beds and could usually only seat two people. Later, tall furniture would become popular in China.[61]

Israel

In Ancient Israel King Solomon supposedly had a bed made of cedar, silver, and gold. Most people would sleep on mats, rich people had real beds with pillows. The pillows would be made from goatskins filled with feathers or wool. Solomon's bed was made from ivory, with linen sheets, and scented with cinnamon and other spices.[62] Israelites had wardrobes made of ivory. They also had some furniture made of wood such as olive wood.[63][64] The Hebrews may have borrowed much of their furniture from other civilizations.[65] Ivories were common in ancient Israeli furniture. The ivories would be used in furniture inlays. The ivories would be carved into round and lace-like plaques. The ivories would have patterns of colored paste with precious stones coated with gold or leaves. Alternatively, they could have the colored paste and stones painted. These ivories would have Phonecian letters inscribed on their backs. The Phonecian letters guided architects on how to use the ivories. Ivories tended to be around beds, chairs, and stools. Ancient Israelites also had cosmetic spoons, cosmetic bottle stoppers, and round pyxides mirror handles.[66][67] Most houses would only have a table and chairs. It is entirely possible instead of a table there would just be a raised piece of earth. They would have cushions and mats and they would eat from a platter of food. Ordinary people would have stools or chairs with footrests and armrests. No chair had upholstery. Solomon had a throne laid with ivory carvings and plated in gold. The throne was six steps higher than the floor.

Mesoamerica

The Aztecs had little furniture. They sat and slept on mats made from reeds. Sometimes Aztecs slept on dirt platforms. Wealthy Aztecs would have curtains and murals around their sleeping areas.[68] Aztecs kept their belongings in wooden blocks or reed chests.[69]The Aztecs also had digging sticks made by attaching a blade to a long stick. Digging sticks were used for planting and wedding. Aztecs also had looms, pots, and frying pans, and grinding stones. The grinding stones were used for grinding corn and grinding hunting and fishing gear.[70] The Aztec Tlatoani had chairs and dining tables. The Aztecs also had ceremonial shrines.[71] In one Maya ceramic, a god is shown seated on a throne-like stool covered in cloth placed on a raised platform. In Chichen Itza a carved stone called a chacmool was used to hold offerings in sacrificial ceremonies.[72]

References

- Somervill, Barbara A. (2009). Empires of Ancient Mesopotamia. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60413-157-4.

- "Furniture - History". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-01-11.

- Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea (1998). Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29497-6.

- Nardo, Don (2009-03-17). Ancient Mesopotamia. Greenhaven Publishing LLC. ISBN 978-0-7377-4625-9.

- Scholl, Elizabeth (2010-12-23). In Ancient Mesopotamia. Mitchell Lane Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-1-61228-019-6.

- Gates, Charles (2011-03-21). Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-82328-2.

- Yildiz, Inar. Furniture Styles in History Part II: Ancient Furniture.

- "What Is Ancient Assyrian Art? Discover the Visual Culture of This Powerful Empire". My Modern Met. 2020-12-27. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- Hunter, George Leland (1923). Decorative Furniture: A Picture Book of the Beautiful Forms of All Ages and All Periods ... Good Furniture Magazine ; Dean-Hicks Company.

- Good Furniture & Decoration. National Trade Journals. 1921.

- Alexiou, Platon (2019). Approaching the Ancient Dilmum Furniture. United Arab Emirates: Ajman University. ISBN 978-9948-35-108-5.

- KILLEN, GEOFFREY. Ancient Egyptian Furniture Volume I: 4000 – 1300 BC. 2nd ed., vol. 1, Oxbow Books, 2017. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1m321gz. Accessed 11 Jan. 2021.

- G.M.A. Richter, The Furniture of the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans (London: Phaidon, 1966), 122. First published in 1926 with an updated version in 1966.

- Richter, 125.

- Richter, 125-126.

- Stephanus T. A. M. Mols, Wooden Furniture in Herculaneum: Form, Technique and Function, in vol. 2 of Circumvesuviana (Amsterdam: Gieben, 1999), 10. These relatively simple varieties of furniture may be connected to ancient Greek sumptuary laws. The effects of these laws on craftsmen are discussed by Alison Burford in Craftsmen in Greek and Roman Society (Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1972), 146.

- See section on “Greek Furniture” in Richter, 13-84, in which the author describes Greek furniture and its typology.

- Richter, 13.

- Richter, 14; NH 5.11.2ff.

- Linda Maria Gigante, “Funerary Art,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, Vol. 1, ed. Michael Gagarin and Elaine Fantham (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 246.

- Richter, 49.

- Richter, 50-51.

- E. Guhl, and W. Koner, Everyday Life in Greek and Roman Times (New York: Crescent, 1989), 133.

- Elizabeth Simpson, “Furniture,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, Vol. 1, ed. Michael Gagarin and Elaine Fantham (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 254.

- Dimitra Andrianou, The Furniture and Furnishings of Ancient Greek Houses and Tombs (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009) 28-29, figure 6a.

- Gargain, Michael (2010). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press.

- Ole Wanscher, Sella Curulis: The Folding Stool, an Ancient Symbol of Dignity (Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1980), 83.

- Richter, 43.

- Simpson, 253.

- Richter, 54; Richter defines “turned” (as in lathe-turned) legs on page 19 as being tripartite, with a middle “lozenge-shaped” portion capped by conical, “flaring” pieces at either end. This terminology is problematic in that it implies woodworking techniques, while the “turned” leg could have been executed in other materials, such as stone, metal, or ivory. Richter defines “rectangular” legs on page 23 as those that are “straight” though these can be curved and footed and often decorated with palettes and volutes.

- Andrianou, 36.

- Richter, 117.

- Richter, 63.

- Richter, 66.

- Chicago Painter, stamnos, ca. 450 B.C.E. The Art Institute of Chicago, 1889.22.

- Richter, 97-116.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 363 to 365.

- Lucia Pirzio Biroli Stefanelli, Il bronzo dei romani: arredo e suppellettile (Rome: L’Erma" di Bretschneider, 1991), 140-142.

- Wanscher, 121.

- Roger B. Ulrich, Roman Woodworking (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 221.

- Richter, 101; Ulrich, 215.

- A. T. Croom, Roman Furniture (Stroud, Gloucestershire, Great Britain: Tempus, 2007), 116.

- Richter, 98; Ulrich, 215-216.

- Richter, 98-101.

- Richter, 10. According to Ulrich, Pliny uses the Greek term cathedra instead of solium for wicker armchairs, 215-218. Croom, however, refers to this chair as cathedra on p. 116.

- Croom, 32.

- Ulrich, 232-233.

- Richter, 104; Croom, 110.

- Ulrich, 219.

- Ulrich, 223-224.

- Ulrich, 225.

- Mols, 1.

- Mols, 19.

- Boyce, Charles (2014-01-02). Dictionary of Furniture: Second Edition. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-62873-840-7.

- Litchfield, Frederick (1903). Illustrated History of Furniture. Truslove & hanson.

- India (1851). India, Ancient and Modern; or, the History of Hindostan, civil and military, etc. Cradock & Company.

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1977). Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-0436-4.

- 和子·小泉 (1986). 和家具. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-0-87011-722-0.

- Boyce, Charles (2014-01-02). Dictionary of Furniture: Second Edition. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-62873-840-7.

- Handler, Sarah (2001-10-30). Austere Luminosity of Chinese Classical Furniture. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21484-2.

- Zhang, Xiaoming (2011-03-03). Chinese Furniture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-18646-9.

- Sherman, Josepha (2004-01-01). Your Travel Guide to Ancient Israel. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-3072-5.

- Dever, William G. (2012-04-20). The Lives of Ordinary People in Ancient Israel: When Archaeology and the Bible Intersect. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-6701-8.

- King, Philip J.; Stager, Lawrence E. (2001-01-01). Life in Biblical Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22148-5.

- Pollen, John Hungerford (1886). Ancient and Modern Furniture and Woodwork. Committee of Council on Education.

- Ben-Tor, Amnon (1992-01-01). The Archaeology of Ancient Israel. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05919-9.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2002-03-06). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Isreal and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-2338-6.

- Kenney, Karen Latchana (2015-01-01). Ancient Aztecs. ABDO. ISBN 978-1-62969-298-2.

- DK (2011-08-15). DK Eyewitness Books: Aztec, Inca & Maya: Discover the World of the Aztecs, Incas, and Mayas—their Beliefs, Rituals, and Civilizations. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-7566-8952-0.

- Marty, Lisa (2006-09-01). Ancient Aztecs. Lorenz Educational Press. ISBN 978-0-7877-0614-2.

- Service, Social Studies School (2006). Aztec, Maya, Inca. Social Studies. ISBN 978-1-56004-254-9.

- Pile, John F. (2005). A History of Interior Design. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85669-418-6.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ancient furniture. |

- Andrianou, Dimitra. The Furniture and Furnishings of Ancient Greek Houses and Tombs. New York: Cambridge UP, 2009.

- Baker, Hollis S. Furniture in the Ancient World: Origins & Evolution, 3100-475 B.C. New York: Macmillan, 1966.

- Blakemore, Robbie G. History of Interior Design & Furniture: from Ancient Egypt to Nineteenth-century Europe. Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley & Sons, 2006.

- Boger, Louise Ade. Furniture Past & Present: A Complete Illustrated Guide to Furniture Styles from Ancient to Modern. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1966.

- Burford, Alison. Craftsmen in Greek and Roman Society. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1972.

- Gigante, Linda Maria. “Funerary Art,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Vol. 1. Edited by Michael Gagarin and Elaine Fantham. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Guhl, E., and W. Koner. Everyday Life in Greek and Roman Times. New York: Crescent, 1989.

- Mols, Stephanus T.A.M. Wooden Furniture in Herculaneum: Form, Technique and Function. Vol. 2 of Circumvesuviana. Amsterdam: Gieben, 1999.

- Nevett, Lisa C. Domestic Space in Classical Antiquity. New York: Cambridge UP, 2010.

- Pollen, John Hungerford. Ancient and Modern Furniture and Woodwork. London: Pub. for the Committee of Council on Education, by Chapman and Hall, 1875. South Kensington Museum of Art Handbooks, No. 3.

- Richter, G.M.A. The Furniture of the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans. London: Phaidon, 1966.

- Robsjohn-Gibbings, Terence Harold, and Carlton W. Pullin. Furniture of Classical Greece. New York: Knopf, 1963.

- Simpson, Elizabeth. “Furniture,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Vol. 1. Edited by Michael Gagarin and Elaine Fantham. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Wanscher, Ole. Sella Curulis: The Folding Stool, an Ancient Symbol of Dignity. Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1980.