Xinjiang

Xinjiang (Uighur: شىنجاڭ, SASM/GNC: Xinjang; Chinese: 新疆; pinyin: Xīnjiāng; alternately romanized as Sinkiang), officially Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region[9] (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwest of the country close to Central Asia. Being the largest province-level division of China and the 8th-largest country subdivision in the world, Xinjiang spans over 1.6 million km2 (640,000 square miles) and has about 25 million inhabitants.[1][10]

Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region

شىنجاڭ ئۇيغۇر ئاپتونوم رايونى 新疆维吾尔自治区 | |

|---|---|

| Name transcription(s) | |

| • Chinese | 新疆维吾尔自治区 (Xīnjiāng Wéiwú'ěr Zìzhìqū) |

| • Abbreviation | XJ / 新 (Pinyin: Xīn) |

| • Uyghur | شىنجاڭ ئۇيغۇر ئاپتونوم رايونى |

| • Uyghur transl. | Shinjang Uyghur Aptonom Rayoni |

(clockwise from top)

| |

_(%252Ball_claims_hatched).svg.png.webp) Map showing the location of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region | |

| Coordinates: 41°N 85°E | |

| Sovereign state | |

| Named for | |

| Capital (and largest city) | Ürümqi |

| Divisions | 14 prefectures, 99 counties, 1005 townships |

| Government | |

| • CCP Secretary | Chen Quanguo |

| • Chairman | Shohrat Zakir |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,664,897 km2 (642,820 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 1st |

| Highest elevation (K2) | 8,611 m (28,251 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | −154 m (−505 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 21,815,815 |

| • Estimate (2018)[4] | 24,870,000 |

| • Rank | 25th |

| • Density | 15/km2 (40/sq mi) |

| • Density rank | 29th |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic composition (2010 Census) | |

| • Languages and dialects | |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-XJ |

| GDP (2017 [7]) | CNY 1.1 trillion $162 billion (26th) |

| - per capita | CNY 45,099 USD 6,680 (21st) |

| HDI (2018) | 0.731[8] (high) (27th) |

| Website | Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region |

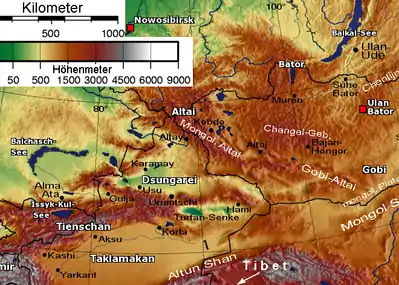

Xinjiang borders the countries of Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India. The rugged Karakoram, Kunlun and Tian Shan mountain ranges occupy much of Xinjiang's borders, as well as its western and southern regions. The Aksai Chin region, administered by China, is claimed by India. Xinjiang also borders the Tibet Autonomous Region and the provinces of Gansu and Qinghai. The most well-known route of the historical Silk Road ran through the territory from the east to its northwestern border.

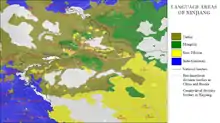

It is home to a number of ethnic groups, including the Turkic Uyghur, Kazakhs and Kyrgyz, the Han, Tibetans, Hui, Tajiks, Mongols, Russians and Xibe.[11] More than a dozen autonomous prefectures and counties for minorities are in Xinjiang. Older English-language reference works often refer to the area as Chinese Turkestan,[12][13] East Turkestan[14] and East Turkistan.[15] Xinjiang is divided into the Dzungarian Basin in the north and the Tarim Basin in the south by a mountain range. Only about 9.7% of Xinjiang's land area is fit for human habitation.[16]

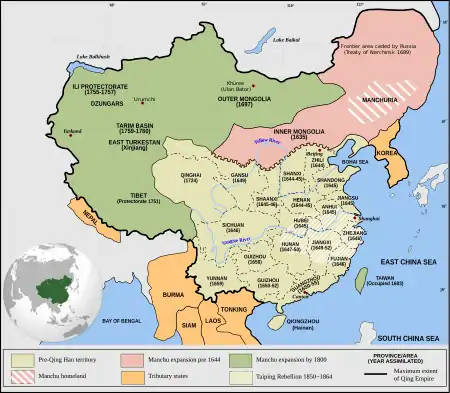

With a documented history of at least 2,500 years, a succession of people and empires have vied for control over all or parts of this territory. The territory came under the rule of the Qing dynasty in the 18th century, later replaced by the Republic of China government. Since 1949 and the Chinese Civil War, it has been part of the People's Republic of China. In 1954, the Xinjiang Bingtuan was set up to strengthen border defense against the Soviet Union and also promote the local economy. In 1955, Xinjiang was administratively changed from a province into an autonomous region. In recent decades, abundant oil and mineral reserves have been found in Xinjiang and it is currently China's largest natural gas-producing region. From the 1990s to the 2010s, the East Turkestan independence movement, separatist conflict and the influence of radical Islam have resulted in unrest in the region with occasional terrorist attacks and clashes between separatist and government forces.[17][18]

Names

| Xinjiang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) "Xīnjiāng" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 新疆 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Xīnjiāng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Sinkiang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "New Frontier" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 新疆维吾尔自治区 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 新疆維吾爾自治區 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Xīnjiāng Wéiwú'ěr Zìzhìqū | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Sinkiang Uyghur Autonomous Region | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | ཞིན་ཅང་ཡུ་གུར་རང་སྐྱོང་ལྗོངས། | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Шиньжян Уйгурын өөртөө засах орон | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠰᠢᠨᠵᠢᠶᠠᠩ ᠤᠶᠢᠭᠤᠷ ᠤᠨ ᠥᠪᠡᠷᠲᠡᠭᠡᠨ ᠵᠠᠰᠠᠬᠤ ᠣᠷᠤᠨ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur | شىنجاڭ ئۇيغۇر ئاپتونوم رايونى | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡳᠴᡝ ᠵᡝᠴᡝᠨ ᡠᡳᡤᡠᡵ ᠪᡝᠶᡝ ᡩᠠᠰᠠᠩᡤᠠ ᡤᠣᠯᠣ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Möllendorff | Ice Jecen Uigur beye dasangga golo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Russian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Russian | Синьцзян | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romanization | Sin'tsjan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kazakh name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kazakh | شينجياڭ ۇيعۇر اۆتونوميالى رايونى Shyńjań Uıǵyr aýtonomııalyq aýdany | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kyrgyz name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kyrgyz | شئنجاڭ ۇيعۇر اپتونوم رايونۇ Шинжаң-Уйгур автоном району Şincañ-Uyğur avtonom rayonu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oirat name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oirat | ᠱᡅᠨᡓᡅᡕᠠᡊ ᡇᡕᡅᡎᡇᠷ ᡅᠨ ᡄᡋᡄᠷᡄᡃᠨ ᠴᠠᠰᠠᡍᡇ ᡆᠷᡇᠨ Šinǰiyang Uyiγur-in ebereen zasaqu orun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Xibe name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Xibe | ᠰᡞᠨᡪᠶᠠᡢ ᡠᡞᡤᡠᠷ ᠪᡝᠶᡝ ᡩᠠᠰᠠᡢᡤᠠ ᡤᠣᠯᠣ Sinjyang Uigur beye dasangga golo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The general region of Xinjiang has been known by many different names in earlier times, in indigenous languages as well as other languages. These names include Altishahr, the historical Uyghur name for the southern half of the region referring to "the six cities" of the Tarim Basin, as well as Khotan, Khotay, Chinese Tartary, High Tartary, East Chagatay (it was the eastern part of the Chagatai Khanate), Moghulistan ("land of the Mongols"), Kashgaria, Little Bokhara, Serindia (due to Indian cultural influence)[19] and, in Chinese, "Western Regions".[20]

In Chinese, under the Han dynasty, Xinjiang was known as Xiyu (西域), meaning "Western Regions". Between the 2nd century BCE and 2nd century CE the Han Empire established the Protectorate of the Western Regions or Xiyu Protectorate (西域都護府) in an effort to secure the profitable routes of the Silk Road.[21] The Western Regions during the Tang era were known as Qixi (磧西). Qi refers to the Gobi Desert while Xi refers to the west. The Tang Empire had established the Protectorate General to Pacify the West or Anxi Protectorate (安西都護府) in 640 to control the region. During the Qing dynasty, the northern part of Xinjiang, Dzungaria was known as Zhunbu (準部, "Dzungar region") and the southern Tarim Basin was known as Huijiang (回疆, "Muslim Frontier") before both regions were merged and became the region of "Xiyu Xinjiang", later simplified as "Xinjiang".

The current Mandarin Chinese-derived name Xinjiang (Sinkiang), which literally means "New Frontier", "New Borderland" or "New Territory", was given during the Qing dynasty by the Guangxu Emperor.[22] According to Chinese statesman Zuo Zongtang's report to the Emperor of Qing, Xinjiang means an "old land newly returned" (故土新歸) or the "new old land".[note 1]

The term was also given to other areas conquered by Chinese empires, for instance, present-day Jinchuan County was then known as "Jinchuan Xinjiang". In the same manner, present-day Xinjiang was known as Xiyu Xinjiang (Chinese: 西域新疆; lit. 'Western Regions' New Frontier') and Gansu Xinjiang (Chinese: 甘肅新疆; lit. 'Gansu Province's New Frontier', especially for present-day eastern Xinjiang).

In 1955, Xinjiang Province was renamed "Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region". The name that was originally proposed was simply "Xinjiang Autonomous Region". Saifuddin Azizi, the first chairman of Xinjiang, registered his strong objections to the proposed name with Mao Zedong, arguing that "autonomy is not given to mountains and rivers. It is given to particular nationalities." As a result, the administrative region would be named "Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region".[24]

Description

Xinjiang consists of two main geographically, historically and ethnically distinct regions with different historical names, Dzungaria north of the Tianshan Mountains and the Tarim Basin south of the Tianshan Mountains, before Qing China unified them into one political entity called Xinjiang Province in 1884. At the time of the Qing conquest in 1759, Dzungaria was inhabited by steppe dwelling, nomadic Tibetan Buddhist Dzungar people, while the Tarim Basin was inhabited by sedentary, oasis dwelling, Turkic-speaking Muslim farmers, now known as the Uyghur people. They were governed separately until 1884. The native Uyghur name for the Tarim Basin is Altishahr.

The Qing dynasty was well aware of the differences between the former Buddhist Mongol area to the north of the Tian Shan and the Turkic Muslim area south of the Tian Shan and ruled them in separate administrative units at first.[25] However, Qing people began to think of both areas as part of one distinct region called Xinjiang.[26] The very concept of Xinjiang as one distinct geographic identity was created by the Qing. It was originally not the native inhabitants who viewed it that way, but rather the Chinese who held that point of view.[27] During the Qing rule, no sense of "regional identity" was held by ordinary Xinjiang people; rather, Xinjiang's distinct identity was given to the region by the Qing, since it had distinct geography, history and culture, while at the same time it was created by the Chinese, multicultural, settled by Han and Hui and separated from Central Asia for over a century and a half.[28]

In the late 19th century, it was still being proposed by some people that two separate regions be created out of Xinjiang, the area north of the Tianshan and the area south of the Tianshan, while it was being argued over whether to turn Xinjiang into a province.[29]

Xinjiang is a large, sparsely populated area, spanning over 1.6 million km2 (comparable in size to Iran), which takes up about one sixth of the country's territory. Xinjiang borders the Tibet Autonomous Region and India's Leh District in Ladakh to the south and Qinghai and Gansu provinces to the southeast, Mongolia (Bayan-Ölgii, Govi-Altai and Khovd Provinces) to the east, Russia's Altai Republic to the north and Kazakhstan (Almaty and East Kazakhstan Regions), Kyrgyzstan (Issyk-Kul, Naryn and Osh Regions), Tajikistan's Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region, Afghanistan's Badakhshan Province, Pakistan (Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan) and India's Jammu and Kashmir to the west.

The east-west chain of the Tian Shan separate Dzungaria in the north from the Tarim Basin in the south. Dzungaria is a dry steppe and the Tarim Basin contains the massive Taklamakan Desert, surrounded by oases. In the east is the Turpan Depression. In the west, the Tian Shan split, forming the Ili River valley.

History

Early history

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Xinjiang |

|

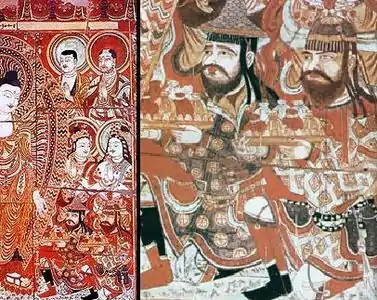

According to J. P. Mallory and Victor H. Mair, the Chinese described "white people with long hair" (the Bai people) in the Shan Hai Jing who lived beyond their northwestern border. The well-preserved Tarim mummies, with Caucasian features (often with reddish or blond hair),[30] displayed in the Ürümqi Museum and dated to the 2nd millennium BC (4,000 years ago), have been found in the same area of the Tarim Basin.[31] Between 2009 and 2015, the remains of 92 individuals in the Xiaohe Cemetery were analyzed for Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA markers. Genetic analyses of the mummies showed that the maternal lineages of the Xiaohe people originated from East Asia and West Eurasia; the paternal lineages all originated in West Eurasia.[32]

Nomadic tribes such as the Yuezhi, Saka, and Wusun were probably part of the migration of Indo-European speakers who had settled in eastern Central Asia, possibly as far as Gansu; the Ordos culture in northern China, east of the Yuezhi, is another example. By the time the Han dynasty under Emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BC) wrested the western Tarim Basin away from its previous overlords (the Xiongnu), it was inhabited by peoples who included the Indo-European Tocharians in Turfan and Kucha and the Indo-Iranian Saka peoples centered in the Shule Kingdom and the Kingdom of Khotan.[33]

Yuezhi culture is documented in the region. The first known reference to the Yuezhi was in 645 BC by the Chinese chancellor Guan Zhong in his work, Guanzi (管子, Guanzi Essays: 73: 78: 80: 81). He described the Yúshì, 禺氏 (or Niúshì, 牛氏), as a people from the north-west who supplied jade to the Chinese from the nearby mountains (also known as Yushi) in Gansu.[34] The longtime jade supply[35] from the Tarim Basin is well-documented archaeologically: "It is well known that ancient Chinese rulers had a strong attachment to jade. All of the jade items excavated from the tomb of Fuhao of the Shang dynasty, more than 750 pieces, were from Khotan in modern Xinjiang. As early as the mid-first millennium BC, the Yuezhi engaged in the jade trade, of which the major consumers were the rulers of agricultural China."[36]

Crossed by the Northern Silk Road,[37] the Tarim and Dzungaria regions were known as the Western Regions. It was inhabited by a number of peoples, including Indo-European Tocharians in Turfan and Kucha and Indo-Iranian Sakas centered around Kashgar and Hotan.[33] At the beginning of the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) the region was ruled by the Xiongnu, a powerful nomadic people based in present-day Mongolia. During the 2nd century BC, the Han dynasty prepared for war against Xiongnu when Emperor Wu of Han dispatched Zhang Qian to explore the mysterious kingdoms to the west and form an alliance with the Yuezhi against the Xiongnu. As a result of the war, the Chinese controlled the strategic region from the Ordos and Gansu corridor to Lop Nor. They separated the Xiongnu from the Qiang people on the south, and gained direct access to the Western Regions. Han China sent Zhang Qian as an envoy to the states of the region, beginning several decades of struggle between the Xiongnu and Han China in which China eventually prevailed. In 60 BC, Han China established the Protectorate of the Western Regions (西域都護府) at Wulei (烏壘, near modern Luntai), to oversee the region as far west as the Pamir Mountains. The protectorate was seized during the civil war against Wang Mang (r. AD 9–23), returning to Han control in 91 due to the efforts of general Ban Chao.

The Western Jin dynasty succumbed to successive waves of invasions by nomads from the north at the beginning of the 4th century. The short-lived kingdoms that ruled northwestern China one after the other, including Former Liang, Former Qin, Later Liang, and Western Liáng, all attempted to maintain the protectorate, with varying degrees of success. After the final reunification of northern China under the Northern Wei empire, its protectorate controlled what is now the southeastern region of Xinjiang. Local states such as Shule, Yutian, Guizi and Qiemo controlled the western region, while the central region around Turpan was controlled by Gaochang, remnants of a state (Northern Liang) that once ruled part of what is now Gansu province in northwestern China.

During the Tang dynasty, a series of expeditions were conducted against the Western Turkic Khaganate and their vassals: the oasis states of southern Xinjiang.[38] Campaigns against the oasis states began under Emperor Taizong with the annexation of Gaochang in 640.[39] The nearby kingdom of Karasahr was captured by the Tang in 644, and the kingdom of Kucha was conquered in 649.[40] The Tang Dynasty then established the Protectorate General to Pacify the West (安西都護府), or Anxi Protectorate, in 640 to control the region.

During the Anshi Rebellion, which nearly destroyed the Tang dynasty, Tibet invaded the Tang on a broad front from Xinjiang to Yunnan. It occupied the Tang capital of Chang'an in 763 for 16 days, and controlled southern Xinjiang by the end of the century. The Uyghur Khaganate took control of northern Xinjiang, much of Central Asia, and Mongolia at the same time.

As Tibet and the Uyghur Khaganate declined in the mid-9th century, the Kara-Khanid Khanate (a confederation of Turkic tribes including the Karluks, Chigils and Yaghmas)[41] controlled western Xinjiang during the 10th and 11th centuries. After the Uyghur Khaganate in Mongolia was destroyed by the Kirghiz in 840, branches of the Uyghurs established themselves in Qocha (Karakhoja) and Beshbalik (near present-day Turfan and Urumchi). The Uyghur state remained in eastern Xinjiang until the 13th century, although it was ruled by foreign overlords. The Kara-Khanids converted to Islam. The Uyghur state in eastern Xinjiang, initially Manichean, later converted to Buddhism.

Remnants of the Liao dynasty from Manchuria entered Xinjiang in 1132, fleeing rebellion by the neighboring Jurchens. They established a new empire, the Qara Khitai, which ruled the Kara-Khanid- and Uyghur-held parts of the Tarim Basin for the next century. Although Khitan and Chinese were the primary administrative languages, Persian and Uyghur were also used.[42]

Islamization

| Part of a series on Islam in China |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

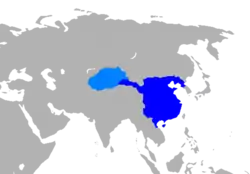

Present-day Xinjiang consisted of the Tarim Basin and Dzungaria, and was originally inhabited by Indo-European Tocharians and Iranian Sakas who practiced Buddhism. The Turfan and Tarim Basins were inhabited by speakers of Tocharian languages,[43] with Caucasian mummies found in the region.[44] The area became Islamified during the 10th century with the conversion of the Kara-Khanid Khanate, who occupied Kashgar. During the mid-10th century, the Saka Buddhist Kingdom of Khotan was attacked by the Turkic Muslim Karakhanid ruler Musa; the Karakhanid leader Yusuf Qadir Khan conquered Khotan around 1006.[45]

Mongol period

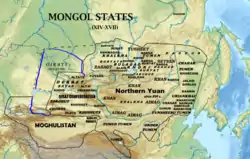

After Genghis Khan unified Mongolia and began his advance west the Uyghur state in the Turpan-Urumchi region offered its allegiance to the Mongols in 1209, contributing taxes and troops to the Mongol imperial effort. In return, the Uyghur rulers retained control of their kingdom; Genghis Khan's Mongol Empire conquered the Qara Khitai in 1218. Xinjiang was a stronghold of Ögedei Khan and later came under the control of his descendant, Kaidu. This branch of the Mongol family kept the Yuan dynasty at bay until their rule ended.

During the Mongol Empire era the Yuan dynasty vied with the Chagatai Khanate for rule of the region, and the latter controlled most of it. After the Chagatai Khanate divided into smaller khanates during the mid-14th century, the politically-fractured region was ruled by a number of Persianized Mongol Khans, including those from Moghulistan (with the assistance of local Dughlat emirs), Uigurstan (later Turpan), and Kashgaria. These leaders warred with each other and the Timurids of Transoxiana to the west and the Oirats to the east: the successor Chagatai regime based in Mongolia and China. During the 17th century, the Dzungars established an empire over much of the region.

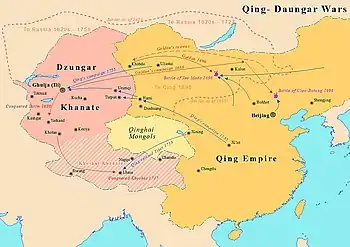

The Mongolian Dzungars were the collective identity of several Oirat tribes which formed, and maintained, one of the last nomadic empires. The Dzungar Khanate covered Dzungaria, extending from the western Great Wall of China to present-day eastern Kazakhstan and from present-day northern Kyrgyzstan to southern Siberia. Most of the region was renamed "Xinjiang" by the Chinese after the fall of the Dzungar Empire, which existed from the early 17th to the mid-18th century.

The sedentary Turkic Muslims of the Tarim Basin were originally ruled by the Chagatai Khanate, and the nomadic Buddhist Oirat Mongols in Dzungaria ruled the Dzungar Khanate. The Naqshbandi Sufi Khojas, descendants of Muhammad, had replaced the Chagatayid Khans as rulers of the Tarim Basin during the early 17th century. There was a struggle between two Khoja factions: the Afaqi (White Mountain) and the Ishaqi (Black Mountain). The Ishaqi defeated the Afaqi, and the Afaq Khoja invited the 5th Dalai Lama (the leader of the Tibetans) to intervene on his behalf in 1677. The Dalai Lama then called on his Dzungar Buddhist followers in the Dzungar Khanate to act on the invitation. The Dzungar Khanate conquered the Tarim Basin in 1680, setting up the Afaqi Khoja as their puppet ruler. After converting to Islam, the descendants of the previously-Buddhist Uyghurs in Turfan believed that the "infidel Kalmuks" (Dzungars) built Buddhist monuments in their region.[46]

Qing dynasty

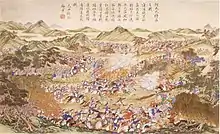

The Turkic Muslims of the Turfan and Kumul oases then submitted to the Qing dynasty, and asked China to free them from the Dzungars; the Qing accepted their rulers as vassals. They warred against the Dzungars for decades before defeating them; Qing Manchu Bannermen then conducted the Dzungar genocide, nearly eradicating them and depopulating Dzungaria. The Qing freed the Afaqi Khoja leader Burhan-ud-din and his brother, Khoja Jihan, from Dzungar imprisonment and appointed them to rule the Tarim Basin as Qing vassals. The Khoja brothers reneged on the agreement, declaring themselves independent leaders of the Tarim Basin. The Qing and the Turfan leader Emin Khoja crushed their revolt, and by 1759 China controlled Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin.

The Manchu Qing dynasty gained control of eastern Xinjiang as a result of a long struggle with the Dzungars which began during the 17th century. In 1755, with the help of the Oirat noble Amursana, the Qing attacked Ghulja and captured the Dzungar khan. After Amursana's request to be declared Dzungar khan went unanswered, he led a revolt against the Qing. Qing armies destroyed the remnants of the Dzungar Khanate over the next two years, and many Han Chinese and Hui moved into the pacified areas.[47]

The native Dzungar Oirat Mongols suffered greatly from the brutal campaigns and a simultaneous smallpox epidemic. Writer Wei Yuan described the resulting desolation in present-day northern Xinjiang as "an empty plain for several thousand li, with no Oirat yurt except those surrendered."[48] It has been estimated that 80 percent of the 600,000 (or more) Dzungars died from a combination of disease and warfare,[49] and recovery took generations.[50]

Han and Hui merchants were initially only allowed to trade in the Tarim Basin; their settlement in the Tarim Basin was banned until the 1830 Muhammad Yusuf Khoja invasion, when the Qing rewarded merchants for fighting off Khoja by allowing them to settle in the basin.[51] The Uyghur Muslim Sayyid and Naqshbandi Sufi rebel of the Afaqi suborder, Jahangir Khoja was sliced to death (Lingchi) in 1828 by the Manchus for leading a rebellion against the Qing. According to Robert Montgomery Martin, many Chinese with a variety of occupations were settled in Dzungaria in 1870; in Turkestan (the Tarim Basin), however, only a few Chinese merchants and garrison soldiers were interspersed with the Muslim population.[52]

The 1765 Ush rebellion by the Uyghurs against the Manchu began after Uyghur women were raped by the servants and son of Manchu official Su-cheng.[53] It was said that "Ush Muslims had long wanted to sleep on [Sucheng and son's] hides and eat their flesh" because of the months-long abuse.[54] The Manchu emperor ordered the massacre of the Uyghur rebel town; Qing forces enslaved the Uyghur children and women, and killed the Uyghur men.[55] Sexual abuse of Uyghur women by Manchu soldiers and officials triggered deep Uyghur hostility against Manchu rule.[56]

Yettishar

By the 1860s, Xinjiang had been under Qing rule for a century. The region was captured in 1759 from the Dzungar Khanate,[57] whose population (the Oirats) became the targets of genocide. Xinjiang was primarily semi-arid or desert and unattractive to non-trading Han settlers, and others (including the Uyghurs) settled there.

The Dungan Revolt by the Muslim Hui and other Muslim ethnic groups was fought in China's Shaanxi, Ningxia and Gansu provinces and in Xinjiang from 1862 to 1877. The conflict led to a reported 20.77 million deaths due to migration and war, with many refugees dying of starvation.[58] Thousands of Muslim refugees from Shaanxi fled to Gansu; some formed battalions in eastern Gansu, intending to reconquer their lands in Shaanxi. While the Hui rebels were preparing to attack Gansu and Shaanxi, Yaqub Beg (an Uzbek or Tajik commander of the Kokand Khanate) fled from the khanate in 1865 after losing Tashkent to the Russians. Beg settled in Kashgar, and soon controlled Xinjiang. Although he encouraged trade, built caravansareis, canals and other irrigation systems, his regime was considered harsh. The Chinese took decisive action against Yettishar; an army under General Zuo Zongtang rapidly approached Kashgaria, reconquering it on 16 May 1877.[59]

After reconquering Xinjiang in the late 1870s from Yaqub Beg,[60] the Qing dynasty established Xinjiang ("new frontier") as a province in 1884[61] – maiking it part of China, and dropping the old names of Zhunbu (準部, Dzungar Region) and Huijiang (Muslimland).[62][63]

After Xinjiang became a Chinese province, the Qing government encouraged the Uyghurs to migrate from southern Xinjiang to other areas of the province (such as the region between Qitai and the capital, largely inhabited by Han Chinese, and Ürümqi, Tacheng (Tabarghatai), Yili, Jinghe, Kur Kara Usu, Ruoqiang, Lop Nor and the lower Tarim River.[64]

Republic of China

In 1912, the Qing dynasty was replaced by the Republic of China. Yuan Dahua, the last Qing governor of Xinjiang, fled. One of his subordinates, Yang Zengxin, took control of the province and acceded in name to the Republic of China in March of that year. Balancing mixed ethnic constituencies, Yang controlled Xinjiang until his 1928 assassination after the Northern Expedition of the Kuomintang.[65]

The Kumul Rebellion and others broke out throughout Xinjiang during the early 1930s against Jin Shuren, Yang's successor, involving Uyghurs, other Turkic groups and Hui (Muslim) Chinese. Jin enlisted White Russians to crush the revolts. In the Kashgar region on 12 November 1933, the short-lived First East Turkestan Republic was self-proclaimed after debate about whether it should be called "East Turkestan" or "Uyghuristan".[66][67] The region claimed by the ETR encompassed the Kashgar, Khotan and Aksu Prefectures in southwestern Xinjiang.[68] The Chinese Muslim Kuomintang 36th Division (National Revolutionary Army) defeated the army of the First East Turkestan Republic in the 1934 Battle of Kashgar, ending the republic after Chinese Muslims executed its two emirs: Abdullah Bughra and Nur Ahmad Jan Bughra. The Soviet Union invaded the province; it was brought under the control of northeast Han warlord Sheng Shicai after the 1937 Xinjiang War. Sheng ruled Xinjiang for the next decade with support from the Soviet Union, many of whose ethnic and security policies he instituted. The Soviet Union maintained a military base in the province and deployed several military and economic advisors. Sheng invited a group of Chinese Communists to Xinjiang (including Mao Zedong's brother, Mao Zemin), but executed them all in 1943 in fear of a conspiracy. In 1944, President and Premier of China Chiang Kai-shek, informed by the Soviet Union of Shicai's intention to join it, transferred him to Chongqing as the Minister of Agriculture and Forestry the following year.[69] A Soviet-backed Second East Turkestan Republic was established that year, which lasted until 1949 in present-day Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture (Ili, Tarbagatay and Altay Districts) in northern Xinjiang.

People's Republic of China

During the Ili Rebellion, the Soviet Union backed Uyghur separatists to form the Second East Turkestan Republic (2nd ETR) in the Ili region while most of Xinjiang remained under Kuomintang control.[66] The People's Liberation Army entered Xinjiang in 1949, when Kuomintang commander Tao Zhiyue and government chairman Burhan Shahidi surrendered the province to them.[67] Five ETR leaders who were to negotiate with the Chinese about ETR sovereignty died in an air crash that year in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic.[70]

The PRC autonomous region was established on 1 October 1955, replacing the province;[67] that year (the first modern census in China was taken in 1953), Uyghurs were 73 percent of Xinjiang's total population of 5.11 million.[24] Although Xinjiang was designated a "Uygur Autonomous Region" since 1954, more than 50 percent of its area is designated autonomous areas for 13 native non-Uyghur groups.[71] Modern Uyghurs developed ethnogenesis in 1955, when the PRC recognized formerly separately self-identified oasis peoples.[72]

Southern Xinjiang is home to most of the Uyghur population (about nine million people); ninety percent of the Han population, mainly urban, live in northern Xinjiang.[73][74] This created an economic imbalance, since the northern Junghar basin (Dzungaria) is more developed than the south.[75]

Since Chinese economic reform since the late 1970s has exacerbated uneven regional development, more Uyghurs have migrated to Xinjiang's cities and some Han have migrated to Xinjiang for economic advancement. Deng Xiaoping made a nine-day visit to Xinjiang in 1981 and described the region as "unsteady".[76] Increased ethnic contact and labor competition coincided with Uyghur terrorism since the 1990s, such as the 1997 Ürümqi bus bombings.[77]

In 2000, Uyghurs were 45 percent of Xinjiang's population and 13 percent of Ürümqi's population. With nine percent of Xinjiang's population, Ürümqi accounts for 25 percent of the region's GDP; many rural Uyghurs have migrated to the city for work in its light, heavy and petrochemical industries.[78] Han in Xinjiang are older, better-educated and work in higher-paying professions than their Uyghur counterparts. Han are more likely to cite business reasons for moving to Ürümqi, while some Uyghurs cite legal trouble at home and family reasons for moving to the city.[79] Han and Uyghurs are equally represented in Ürümqi's floating population, which works primarily in commerce. Auto-segregation in the city is widespread in residential concentration, employment relationships and endogamy.[80] In 2010, Uyghurs were a majority in the Tarim Basin and a plurality in Xinjiang as a whole.[81]

Xinjiang has 81 public libraries and 23 museums, compared to none in 1949. It has 98 newspapers in 44 languages, compared with four in 1952. According to official statistics, the ratio of doctors, medical workers, clinics and hospital beds to the general population surpasses the national average; the immunization rate has reached 85 percent%.[82]

The ongoing Xinjiang conflict[83][84] includes the 2007 Xinjiang raid,[85] a thwarted 2008 suicide-bombing attempt on a China Southern Airlines flight,[86] the 2008 Kashgar attack which killed 16 police officers four days before the Beijing Olympics,[87][88] the August 2009 syringe attacks,[89] the 2011 Hotan attack,[90] the 2014 Kunming attack,[91] the April 2014 Ürümqi attack,[92] and the May 2014 Ürümqi attack.[93] Several of the attacks were orchestrated by the Turkistan Islamic Party (formerly the East Turkestan Islamic Movement), identified as a terrorist group by several entities (including Russia,[94] Turkey,[95][96] the United Kingdom,[97] the United States until October 2020,[98][99] and the United Nations).[100]

According to Human Rights Watch, Chinese authorities have operated Xinjiang re-education camps to indoctrinate Uyghurs and other Muslims as part of a "people's war on terror" since 2017.[101][102] The camps have been criticized by a number of countries and human-rights organizations for abuse and mistreatment, with some alleging Uyghur genocide.[103] In 2020, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping affirmed the party's policies in Xinjiang: "Practice has proven that the party's strategy for governing Xinjiang in the new era is completely correct."[104]

Administrative divisions

Xinjiang is divided into thirteen prefecture-level divisions: four prefecture-level cities, six prefectures and five autonomous prefectures (including the sub-provincial autonomous prefecture of Ili, which in turn has two of the seven prefectures within its jurisdiction) for Mongol, Kazakh, Kyrgyz and Hui minorities. At the end of the year 2017, the total population of Xinjiang was 24.45 million.[105]

These are then divided into 13 districts, 25 county-level cities, 62 counties and 6 autonomous counties. Ten of the county-level cities do not belong to any prefecture and are de facto administered by the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps. Sub-level divisions of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region is shown in the adjacent picture and described in the table below:

| Administrative divisions of Xinjiang | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png.webp)

█ XPCC / Bingtuan administered

county-level divisions █ Subordinate to Ili Kazakh A.P.

☐ Disputed areas claimed by India

and administered by China (see Sino-Indian border dispute) | |||||||||||||

| Division code[106] | Division | Area in km2[107] | Population 2010[108] | Seat | Divisions[109] | ||||||||

| Districts | Counties | Aut. counties | CL cities | ||||||||||

| 650000 | Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region | 1664900.00 | 21,813,334 | Ürümqi city | 13 | 61 | 6 | 26 | |||||

| 650100 | Ürümqi city | 13787.90 | 3,110,280 | Tianshan District | 7 | 1 | |||||||

| 650200 | Karamay city | 8654.08 | 391,008 | Karamay District | 4 | ||||||||

| 650400 | Turpan city | 67562.91 | 622,679 | Gaochang District | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| 650500 | Hami city | 142094.88 | 572,400 | Yizhou District | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 652300 | Changji Hui Autonomous Prefecture | 73139.75 | 1,428,592 | Changji city | 4 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| 652700 | Bortala Mongol Autonomous Prefecture | 24934.33 | 443,680 | Bole city | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| 652800 | Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture | 470954.25 | 1,278,492 | Korla city | 7 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 652900 | Aksu Prefecture | 127144.91 | 2,370,887 | Aksu city | 7 | 2 | |||||||

| 653000 | Kizilsu Kyrgyz Autonomous Prefecture | 72468.08 | 525,599 | Artux city | 3 | 1 | |||||||

| 653100 | Kashgar Prefecture | 137578.51 | 3,979,362 | Kashi city | 10 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 653200 | Hotan Prefecture | 249146.59 | 2,014,365 | Hotan city | 7 | 1 | |||||||

| 654000 | Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture | 56381.53 * | 2,482,627 * | Yining city | 7 * | 1 * | 3 * | ||||||

| 654200 | Tacheng Prefecture* | 94698.18 | 1,219,212 | Tacheng city | 4 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| 654300 | Altay Prefecture* | 117699.01 | 526,980 | Altay city | 6 | 1 | |||||||

| 659000 | Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps | 13055.57 | 1,481,165 | Ürümqi city | 10 | ||||||||

| 659001 | Shihezi city (8th Division) | 456.84 | 635,582 | Hongshan Subdistrict | 1 | ||||||||

| 659002 | Aral city (1st Division) | 5266.00 | 190,613 | Jinyinchuan Road Subdistrict | 1 | ||||||||

| 659003 | Tumxuk city (3rd Division) | 2003.00 | 174,465 | Qiganquele Subdistrict | 1 | ||||||||

| 659004 | Wujiaqu city (6th Division) | 742.00 | 90,205 | Renmin Road Subdistrict | 1 | ||||||||

| 659005 | Beitun city (10th Division) | 910.50 | 86,300 | Xincheng Subdistrict | 1 | ||||||||

| 659006 | Tiemenguan city (2nd Division) | 590.27 | 50,000 | Chengqu Subdistrict | 1 | ||||||||

| 659007 | Shuanghe city (5th Division) | 742.18 | 53,800 | Tasierhai town | 1 | ||||||||

| 659008 | Kokdala city (4th Division) | 979.71 | 75,000 | Jieliangzi Subdistrict | 1 | ||||||||

| 659009 | Kunyu city (14th Division) | 687.13 | 45,200 | Kunyu town | 1 | ||||||||

| 659010 | Huyanghe city (7th Division) | 677.94 | 80,000 | Gongqing town | 1 | ||||||||

|

* – Altay Prefecture or Tacheng Prefecture are subordinate to Ili Prefecture. / The population or area figures of Ili do not include Altay Prefecture or Tacheng Prefecture which are subordinate to Ili Prefecture. | |||||||||||||

| Administrative divisions in Uyghur, Chinese and varieties of romanizations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Uyghur | SASM/GNC Uyghur Pinyin | Chinese | Pinyin |

| Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region | شىنجاڭ ئۇيغۇر ئاپتونوم رايونى | Xinjang Uyĝur Aptonom Rayoni | 新疆维吾尔自治区 | Xīnjiāng Wéiwú'ěr Zìzhìqū |

| Ürümqi city | ئۈرۈمچى شەھىرى | Ürümqi Xäĥiri | 乌鲁木齐市 | Wūlǔmùqí Shì |

| Karamay city | قاراماي شەھىرى | K̂aramay Xäĥiri | 克拉玛依市 | Kèlāmǎyī Shì |

| Turpan city | تۇرپان شەھىرى | Turpan Xäĥiri | 吐鲁番市 | Tǔlǔfān Shì |

| Hami city | قۇمۇل شەھىرى | K̂umul Xäĥiri | 哈密市 | Hāmì Shì |

| Changji Hui Autonomous Prefecture | سانجى خۇيزۇ ئاپتونوم ئوبلاستى | Sanji Huyzu Aptonom Oblasti | 昌吉回族自治州 | Chāngjí Huízú Zìzhìzhōu |

| Bortala Mongol Autonomous Prefecture | بۆرتالا موڭغۇل ئاپتونوم ئوبلاستى | Börtala Mongĝul Aptonom Oblasti | 博尔塔拉蒙古自治州 | Bó'ěrtǎlā Měnggǔ Zìzhìzhōu |

| Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture | بايىنغولىن موڭغۇل ئاپتونوم ئوبلاستى | Bayinĝolin Mongĝul Aptonom Oblasti | 巴音郭楞蒙古自治州 | Bāyīnguōlèng Měnggǔ Zìzhìzhōu |

| Aksu Prefecture | ئاقسۇ ۋىلايىتى | Ak̂su Vilayiti | 阿克苏地区 | Ākèsū Dìqū |

| Kizilsu Kirghiz Autonomous Prefecture | قىزىلسۇ قىرغىز ئاپتونوم ئوبلاستى | K̂izilsu K̂irĝiz Aptonom Oblasti | 克孜勒苏柯尔克孜自治州 | Kèzīlèsū Kē'ěrkèzī Zìzhìzhōu |

| Kashi Prefecture | قەشقەر ۋىلايىتى | K̂äxk̂är Vilayiti | 喀什地区 | Kāshí Dìqū |

| Hotan Prefecture | خوتەن ۋىلايىتى | Hotän Vilayiti | 和田地区 | Hétián Dìqū |

| Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture | ئىلى قازاق ئاپتونوم ئوبلاستى | Ili K̂azak̂ Aptonom Oblasti | 伊犁哈萨克自治州 | Yīlí Hāsàkè Zìzhìzhōu |

| Tacheng Prefecture | تارباغاتاي ۋىلايىتى | Tarbaĝatay Vilayiti | 塔城地区 | Tǎchéng Dìqū |

| Altay Prefecture | ئالتاي ۋىلايىتى | Altay Vilayiti | 阿勒泰地区 | Ālètài Dìqū |

| Shihezi city | شىخەنزە شەھىرى | Xihänzä Xäĥiri | 石河子市 | Shíhézǐ Shì |

| Aral city | ئارال شەھىرى | Aral Xäĥiri | 阿拉尔市 | Ālā'ěr Shì |

| Tumxuk city | تۇمشۇق شەھىرى | Tumxuk̂ Xäĥiri | 图木舒克市 | Túmùshūkè Shì |

| Wujiaqu city | ۋۇجياچۈ شەھىرى | Vujyaqü Xäĥiri | 五家渠市 | Wǔjiāqú Shì |

| Beitun city | بەيتۈن شەھىرى | Bäatün Xäĥiri | 北屯市 | Běitún Shì |

| Tiemenguan city | باشئەگىم شەھىرى | Baxägym Xäĥiri | 铁门关市 | Tiĕménguān Shì |

| Shuanghe city | قوشئۆگۈز شەھىرى | K̂oxögüz Xäĥiri | 双河市 | Shuānghé Shì |

| Kokdala city | كۆكدالا شەھىرى | Kökdala Xäĥiri | 可克达拉市 | Kěkèdálā Shì |

| Kunyu city | قۇرۇمقاش شەھىرى | Kurumkax Xäĥiri | 昆玉市 | Kūnyù Shì |

| Huyanghe city | خۇياڭخې شەھىرى | Huyanghê Xäĥiri | 胡杨河市 | Húyánghé Shì |

Urban areas

| Population by urban areas of prefecture & county cities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | City | Urban area[110] | District area[110] | City proper[110] | Census date |

| 1 | Ürümqi | 2,853,398 | 3,029,372 | 3,112,559 | 2010-11-01 |

| 2 | Korla | 425,182 | 549,324 | part of Bayingolin Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

| 3 | Yining | 368,813 | 515,082 | part of Ili Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

| 4 | Karamay | 353,299 | 391,008 | 391,008 | 2010-11-01 |

| 5 | Shihezi | 313,768 | 380,130 | 380,130 | 2010-11-01 |

| 6 | Hami[lower-roman 1] | 310,500 | 472,175 | 572,400 | 2010-11-01 |

| 7 | Kashi | 310,448 | 506,640 | part of Kashi Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

| 8 | Changji | 303,938 | 426,253 | part of Changji Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

| 9 | Aksu | 284,872 | 535,657 | part of Aksu Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

| 10 | Usu | 131,661 | 298,907 | part of Tacheng Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

| 11 | Bole | 120,138 | 235,585 | part of Bortala Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

| 12 | Hotan | 119,804 | 322,300 | part of Hotan Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

| 13 | Altay | 112,711 | 190,064 | part of Altay Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

| 14 | Turpan[lower-roman 2] | 89,719 | 273,385 | 622,903 | 2010-11-01 |

| 15 | Tacheng | 75,122 | 161,037 | part of Tacheng Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

| 16 | Wujiaqu | 75,088 | 96,436 | 96,436 | 2010-11-01 |

| 17 | Fukang | 67,598 | 165,006 | part of Changji Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

| 18 | Aral | 65,175 | 158,593 | 158,593 | 2010-11-01 |

| 19 | Artux | 58,427 | 240,368 | part of Kizilsu Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

| (–) | Beitun[lower-roman 3] | 57,889 | 57,889 | 57,889 | 2010-11-01 |

| (–) | Kokdala[lower-roman 4] | 57,537 | 57,537 | 57,537 | 2010-11-01 |

| (–) | Shuanghe[lower-roman 5] | 53,565 | 53,565 | 53,565 | 2010-11-01 |

| (–) | Korgas[lower-roman 6] | 51,462 | 51,462 | part of Ili Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

| (–) | Kunyu[lower-roman 7] | 36,399 | 36,399 | 36,399 | 2010-11-01 |

| 20 | Tumxuk | 34,808 | 135,727 | 135,727 | 2010-11-01 |

| (–) | Tiemenguan[lower-roman 8] | 30,244 | 30,244 | 30,244 | 2010-11-01 |

| 21 | Kuytun | 20,805 | 166,261 | part of Ili Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

| (–) | Alashankou[lower-roman 9] | 15,492 | 15,492 | part of Bortala Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

- Hami Prefecture is currently known as Hami PLC after census; Hami CLC is currently known as Yizhou after census.

- Turpan Prefecture is currently known as Turpan PLC after census; Turpan CLC is currently known as Gaochang after census.

- Beitun CLC was established from parts of Altay CLC after census.

- Kokdala CLC was established from parts of Huocheng County after census.

- Shuanghe CLC was established from parts of Bole CLC after census.

- Korgas CLC was established from parts of Huocheng County after census.

- Kunyu CLC was established from parts of Hotan County, Pishan County, Moyu County, & Qira County after census.

- Tiemenguan CLC was established from parts of Korla CLC after census.

- Alashankou CLC was established from parts of Bole CLC & Jinghe County after census.

Geography and geology

Xinjiang is the largest political subdivision of China, accounting for more than one sixth of China's total territory and a quarter of its boundary length. Xinjiang is mostly covered with uninhabitable deserts and dry grasslands, with dotted oases conducive to habitation accounting for 9.7% of Xinjiang's total area by 2015 [16] at the foot of Tian Shan, Kunlun Mountains and Altai Mountains, respectively.

Mountain systems and basins

Xinjiang is split by the Tian Shan mountain range (تەڭرى تاغ, Tengri Tagh, Тәңри Тағ), which divides it into two large basins: the Dzungarian Basin in the north and the Tarim Basin in the south. A small V-shaped wedge between these two major basins, limited by the Tian Shan's main range in the south and the Borohoro Mountains in the north, is the basin of the Ili River, which flows into Kazakhstan's Lake Balkhash; an even smaller wedge farther north is the Emin Valley.

Other major mountain ranges of Xinjiang include the Pamir Mountains and Karakoram in the southwest, the Kunlun Mountains in the south (along the border with Tibet) and the Altai Mountains in the northeast (shared with Mongolia). The region's highest point is the mountain K2, an eight-thousander located 8,611 meters (28,251 ft) above sea level in the Karakoram Mountains on the border with Pakistan.

Much of the Tarim Basin is dominated by the Taklamakan Desert. North of it is the Turpan Depression, which contains the lowest point in Xinjiang and in the entire PRC, at 155 meters (509 ft) below sea level.

The Dzungarian Basin is slightly cooler, and receives somewhat more precipitation, than the Tarim Basin. Nonetheless, it, too, has a large Gurbantünggüt Desert (also known as Dzoosotoyn Elisen) in its center.

The Tian Shan mountain range marks the Xinjiang-Kyrgyzstan border at the Torugart Pass (3752 m). The Karakorum highway (KKH) links Islamabad, Pakistan with Kashgar over the Khunjerab Pass.

Mountain Pass

From south to north, the mountain passes bordering Xinjiang are:

Geology

Xinjiang is geologically young. Collision of the Indian and the Eurasian plates formed the Tian Shan, Kunlun Shan, and Pamir mountain ranges; said tectonics render it a very active earthquake zone. Older geological formations are located in the far north, where the Junggar Block is geologically part of Kazakhstan, and in the east, where is part of the North China Craton.

Center of the continent

Xinjiang has within its borders, in the Dzoosotoyn Elisen Desert, the location in Eurasia that is furthest from the sea in any direction (a continental pole of inaccessibility): 46°16.8′N 86°40.2′E. It is at least 2,647 km (1,645 mi) (straight-line distance) from any coastline.

In 1992, local geographers determined another point within Xinjiang – 43°40′52″N 87°19′52″E in the southwestern suburbs of Ürümqi, Ürümqi County – to be the "center point of Asia". A monument to this effect was then erected there and the site has become a local tourist attraction.[111]

Rivers and lakes

Having hot summer and low precipitation, most of Xinjiang is endorheic. Its rivers either disappear in the desert, or terminate in salt lakes (within Xinjiang itself, or in neighboring Kazakhstan), instead of running towards an ocean. The northernmost part of the region, with the Irtysh River rising in the Altai Mountains, that flows (via Kazakhstan and Russia) toward the Arctic Ocean, is the only exception. But even so, a significant part of the Irtysh's waters were artificially diverted via the Irtysh–Karamay–Ürümqi Canal to the drier regions of southern Dzungarian Basin.

Elsewhere, most of Xinjiang's rivers are comparatively short streams fed by the snows of the several ranges of the Tian Shan. Once they enter the populated areas in the mountains' foothills, their waters are extensively used for irrigation, so that the river often disappears in the desert instead of reaching the lake to whose basin it nominally belongs. This is the case even with the main river of the Tarim Basin, the Tarim, which has been dammed at a number of locations along its course, and whose waters have been completely diverted before they can reach the Lop Lake. In the Dzungarian basin, a similar situation occurs with most rivers that historically flowed into Lake Manas. Some of the salt lakes, having lost much of their fresh water inflow, are now extensively use for the production of mineral salts (used e.g., in the manufacturing of potassium fertilizers); this includes the Lop Lake and the Manas Lake.

Time

Xinjiang is in the same time zone as the rest of China, Beijing time, UTC+8. But while Xinjiang being about two time zones west of Beijing, some residents, local organizations and governments watch another time standard known as Xinjiang Time, UTC+6.[112] Han people tend to use Beijing Time, while Uyghurs tend to use Xinjiang Time as a form of resistance to Beijing.[113] But, regardless of the time standard preferences, most businesses, schools open and close two hours later than in the other regions of China.[114]

Deserts

Deserts include:

- Gurbantünggüt Desert, also known as Dzoosotoyn Elisen

- Taklamakan Desert

- Kumtag Desert, east of Taklamakan

Major cities

Due to water scarcity, most of Xinjiang's population lives within fairly narrow belts that are stretched along the foothills of the region's mountain ranges in areas conducive to irrigated agriculture. It is in these belts where most of the region's cities are found.

Climate

A semiarid or desert climate (Köppen BSk or BWk, respectively) prevails in Xinjiang. The entire region has great seasonal differences in temperature with cold winters. The Turpan Depression recorded the hottest temperatures nationwide in summer,[115] with air temperatures easily exceeding 40 °C (104 °F). Winter temperatures regularly fall below −20 °C (−4 °F) in the far north and highest mountain elevations.

Continuous permafrost is typically found in the Tian Shan starting at the elevation of about 3,500–3,700 m above sea level. Discontinuous alpine permafrost usually occurs down to 2,700–3,300 m, but in certain locations, due to the peculiarity of the aspect and the microclimate, it can be found at elevations as low as 2,000 m.[116]

Politics

.jpg.webp)

- Secretaries of the CCP Xinjiang Committee

- 1949–1952 Wang Zhen (王震)

- 1952–1967 Wang Enmao (王恩茂)

- 1970–1972 Long Shujin (龙书金)

- 1972–1978 Saifuddin Azizi (赛福鼎·艾则孜; سەيپىدىن ئەزىزى)

- 1978–1981 Wang Feng (汪锋)

- 1981–1985 Wang Enmao (王恩茂)

- 1985–1994 Song Hanliang (宋汉良)

- 1994–2010 Wang Lequan (王乐泉)

- 2010–2016 Zhang Chunxian (张春贤)

- 2016–present Chen Quanguo (陈全国)

- Chairmen of the Xinjiang Government

- 1949–1955 Burhan Shahidi (包尔汉·沙希迪; بۇرھان شەھىدى)

- 1955–1967 Saifuddin Azizi (赛福鼎·艾则孜; سەيپىدىن ئەزىزى)

- 1968–1972 Long Shujin (龙书金)

- 1972–1978 Saifuddin Azizi (赛福鼎·艾则孜; سەيپىدىن ئەزىزى)

- 1978–1979 Wang Feng (汪锋)

- 1979–1985 Ismail Amat (司马义·艾买提; ئىسمائىل ئەھمەد)

- 1985–1993 Tömür Dawamat (铁木尔·达瓦买提; تۆمۈر داۋامەت)

- 1993–2003 Abdul'ahat Abdulrixit (阿不来提·阿不都热西提; ئابلەت ئابدۇرىشىت)

- 2003–2007 Ismail Tiliwaldi (司马义·铁力瓦尔地; ئىسمائىل تىلىۋالدى)

- 2007–2015 Nur Bekri (努尔·白克力; نۇر بەكرى)

- 2015–present Shohrat Zakir (雪克来提·扎克尔; شۆھرەت زاكىر)

Human rights

Human Rights Watch has documented the denial of due legal process and fair trials and failure to hold genuinely open trials as mandated by law e.g. to suspects arrested following ethnic violence in the city of Ürümqi's 2009 riots.[117]

According to the Radio Free Asia and Human Rights Watch, at least 120,000 members of Kashgar's Muslim Uyghur minority have been detained in Xinjiang's re-education camps, aimed at changing the political thinking of detainees, their identities and their religious beliefs.[118][101][119] Reports from the World Uyghur Congress submitted to the United Nations in July 2018 suggest that 1 million Uyghurs are currently being held in the re-education camps. The camps were established under CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping's administration.[120][121]

An October 2018 exposé by the BBC News claimed based on analysis of satellite imagery collected over time that hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs must be interned in the camps, and they are rapidly being expanded.[122] In 2019, The Art Newspaper reported that "hundreds" of writers, artists, and academics had been imprisoned, in what the magazine qualified as an attempt to "punish any form of religious or cultural expression" among Uighurs.[123]

In July 2019, 22 countries—Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK—sent a letter to the UN Human Rights Council, criticizing China for its mass arbitrary detentions and other violations against Muslims in China's Xinjiang region. However, on 12 July, a group of 37 countries submitted a similar letter in defense of China's policies: Algeria, Angola, Bahrain, Belarus, Bolivia, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia, Cameroon, Comoros, Congo, Cuba, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Eritrea, Gabon, Kuwait, Laos, Myanmar, Nigeria, North Korea, Oman, Pakistan, Philippines, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Togo, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe.[124][125] However, in August 2019, Qatar withdrew its signature for 12 July letter, with Qatari Ambassador to the UN Ali Al-Mansouri quoted as: "co-authorizing the aforementioned letter would compromise our foreign policy key priorities".[126][127]

On 28 June 2020, The Associated Press published an investigative report which states that the Chinese government is taking draconian measures to slash birth rates among Uighurs and other minorities as part of a sweeping campaign to curb its Muslim population, even as it encourages some of the country's Han majority to have more children.[128] While individual women have spoken out before about forced birth control, the practice is far more widespread and systematic than previously known, according to an AP investigation based on government statistics, state documents and interviews with 30 ex-detainees, family members and a former detention camp instructor. The campaign over the past four years in the far west region of Xinjiang is leading to what some experts are calling a form of "demographic genocide."[128]

On 28 July 2020, a coalition of over 180 organizations called out dozens of clothing brands and retailers to re-examine and cut any ties they might have to Xinjiang region, where allegations of human rights violations have run rampant for years. The coalition cited "credible investigations and reports" by media outlets, nonprofit groups, government agencies and think tanks to support its claims.[129]

In September 2020, Xi Jinping said "practice has proved that the party's strategy for governing Xinjiang in the new era is completely correct and must be adhered to for a long time." Xi Jinping required the whole CPC to take the implementation of the party's strategy for governing Xinjiang in the new era as a political task, and make efforts to implement it completely and accurately to ensure that Xinjiang work always maintains the correct political direction.[130]

Economy

| Development of GDP | |

|---|---|

| Year | GDP in billions of Yuan |

| 1995 | 82 |

| 2000 | 136 |

| 2005 | 260 |

| 2010 | 544 |

| 2015 | 932 |

| 2020 | 1,380 |

| Source:[131] | |

Xinjiang has traditionally been an agricultural region, but is also rich in minerals and oil.

Nominal GDP was about 932.4 billion RMB (US$140 billion) as of 2015 with an average annual increase of 10.4% for the past four years,[132] due to discovery of the abundant reserves of coal, oil, gas as well as the China Western Development policy introduced by the State Council to boost economic development in Western China.[133] Its per capita GDP for 2009 was 19,798 RMB (US$2,898), with a growth rate of 1.7%.[133] Southern Xinjiang, with 95% non-Han population, has an average per capita income half that of Xinjiang as a whole.[134]

In July 2010, China Daily reported that:

Local governments in China's 19 provinces and municipalities, including Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, Zhejiang and Liaoning, are engaged in the commitment of "pairing assistance" support projects in Xinjiang to promote the development of agriculture, industry, technology, education and health services in the region.[135]

Agriculture and fishing

Main area is of irrigated agriculture. By 2015, the agricultural land area of the region is 631 thousand km2 or 63.1 million ha, of which 6.1 million ha is arable land.[136] In 2016, the total cultivated land rose to 6.2 million ha, with the crop production reaching 15.1 million tons.[137] Wheat was the main staple crop of the region, maize grown as well, millet found in the south, while only a few areas (in particular, Aksu) grew rice.[138]

Cotton became an important crop in several oases, notably Khotan, Yarkand and Turpan by the late 19th century.[138] Sericulture is also practiced.[139] Xinjiang is the world's largest cotton exporter, producing 84% of Chinese cotton while the country provides 26% of global cotton export.[140]

Xinjiang is famous for its grapes, melons, pears, walnuts, particularly Hami melons and Turpan raisins. The region is also a leading source for tomato paste, which it supplies for international brands.[140]

The main livestock of the region have traditionally been sheep. Much of the region's pasture land is in its northern part, where more precipitation is available,[141] but there are mountain pastures throughout the region.

Due to the lack of access to the ocean and limited amount of inland water, Xinjiang's fish resources are somewhat limited. Nonetheless, there is a significant amount of fishing in Lake Ulungur and Lake Bosten and in the Irtysh River. A large number of fish ponds have been constructed since the 1970s, their total surface exceeding 10,000 hectares by the 1990s. In 2000, the total of 58,835 tons of fish was produced in Xinjiang, 85% of which came from aquaculture.[142]

In the past, the Lop Lake was known for its fisheries and the area residents, for their fishing culture; now, due to the diversion of the waters of the Tarim River, the lake has dried out.

Mining and minerals

Xinjiang was known for producing salt, soda, borax, gold, jade in the 19th century.[143]

The oil and gas extraction industry in Aksu and Karamay is growing, with the West–East Gas Pipeline linking to Shanghai. The oil and petrochemical sector get up to 60 percent of Xinjiang's economy.[144] Containing over a fifth of China's coal, natural gas and oil resources, Xinjiang has the highest concentration of fossil fuel reserves of any region in the country.[145]

Foreign trade

Xinjiang's exports amounted to US$19.3 billion, while imports turned out to be US$2.9 billion in 2008. Most of the overall import/export volume in Xinjiang was directed to and from Kazakhstan through Ala Pass. China's first border free trade zone (Horgos Free Trade Zone) was located at the Xinjiang-Kazakhstan border city of Horgos.[146] Horgos is the largest "land port" in China's western region and it has easy access to the Central Asian market. Xinjiang also opened its second border trade market to Kazakhstan in March 2006, the Jeminay Border Trade Zone.[147]

Economic and Technological Development Zones

- Bole Border Economic Cooperation Area[148]

- Shihezi Border Economic Cooperation Area[149]

- Tacheng Border Economic Cooperation Area[150]

- Ürümqi Economic & Technological Development Zone is northwest of Ürümqi. It was approved in 1994 by the State Council as a national level economic and technological development zones. It is 1.5 km (0.93 mi) from the Ürümqi International Airport, 2 km (1.2 mi) from the North Railway Station and 10 km (6.2 mi) from the city center. Wu Chang Expressway and 312 National Road passes through the zone. The development has unique resources and geographical advantages. Xinjiang's vast land, rich in resources, borders eight countries. As the leading economic zone, it brings together the resources of Xinjiang's industrial development, capital, technology, information, personnel and other factors of production.[151]

- Ürümqi Export Processing Zone is in Urumuqi Economic and Technology Development Zone. It was established in 2007 as a state-level export processing zone.[152]

- Ürümqi New & Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone was established in 1992 and it is the only high-tech development zone in Xinjiang, China. There are more than 3470 enterprises in the zone, of which 23 are Fortune 500 companies. It has a planned area of 9.8 km2 (3.8 sq mi) and it is divided into four zones. There are plans to expand the zone.[153]

- Yining Border Economic Cooperation Area[154]

Culture

Media

The Xinjiang Networking Transmission Limited operates the Urumqi People's Broadcasting Station and the Xinjiang People Broadcasting Station, broadcasting in Mandarin, Uyghur, Kazakh and Mongolian.

In 1995, there were 50 minority-language newspapers published in Xinjiang, including the Qapqal News, the world's only Xibe language newspaper.[155] The Xinjiang Economic Daily is considered one of China's most dynamic newspapers.[156]

For a time after the July 2009 riots, authorities placed restrictions on the internet and text messaging, gradually permitting access to state-controlled websites like Xinhua's,[157] until restoring Internet to the same level as the rest of China on 14 May 2010.[158][159][160]

As reported by the BBC News, "China strictly controls media access to Xinjiang so reports are difficult to verify."[161]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1912[162] | 2,098,000 | — |

| 1928[163] | 2,552,000 | +21.6% |

| 1936–37[164] | 4,360,000 | +70.8% |

| 1947[165] | 4,047,000 | −7.2% |

| 1954[166] | 4,873,608 | +20.4% |

| 1964[167] | 7,270,067 | +49.2% |

| 1982[168] | 13,081,681 | +79.9% |

| 1990[169] | 15,155,778 | +15.9% |

| 2000[170] | 18,459,511 | +21.8% |

| 2010[171] | 21,813,334 | +18.2% |

The earliest Tarim mummies, dated to 1800 BC, are of a Caucasoid physical type.[172] East Asian migrants arrived in the eastern portions of the Tarim Basin about 3000 years ago and the Uyghur peoples appeared after the collapse of the Orkon Uyghur Kingdom, based in modern-day Mongolia, around 842 AD.[173][174]

The Islamization of Xinjiang started around 1000 AD by eliminating Buddhism.[175] Xinjiang Muslim Turkic peoples contain Uyghurs, Kazaks, Kyrgyz, Tatars, Uzbeks; Muslim Iranian peoples comprise Tajiks, Sarikolis/Wakhis (often conflated as Tajiks); Muslim Sino-Tibetan peoples are such as the Hui. Other ethnic groups in the region are Hans, Mongols (Oirats, Daurs, Dongxiangs), Russians, Xibes, Manchus. Around 70,000 Russian immigrants were living in Xinjiang in 1945.[176]

The Han Chinese of Xinjiang arrived at different times from different directions and social backgrounds. There are now descendants of criminals and officials who had been exiled from China during the second half of the 18th and the first half of the 19th centuries; descendants of families of military and civil officers from Hunan, Yunnan, Gansu and Manchuria; descendants of merchants from Shanxi, Tianjin, Hubei and Hunan; and descendants of peasants who started immigrating into the region in 1776.[177]

Some Uyghur scholars claim descent from both the Turkic Uyghurs and the pre-Turkic Tocharians (or Tokharians, whose language was Indo-European); also, Uyghurs often have relatively-fair skin, hair and eyes and other Caucasoid physical traits.

In 2002, there were 9,632,600 males (growth rate of 1.0%) and 9,419,300 females (growth rate of 2.2%). The population overall growth rate was 1.09%, with 1.63% of birth rate and 0.54% mortality rate.

The Qing began a process of settling Han, Hui, and Uyghur settlers into Northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria) in the 18th century. At the start of the 19th century, 40 years after the Qing reconquest, there were around 155,000 Han and Hui Chinese in northern Xinjiang and somewhat more than twice that number of Uyghurs in Southern Xinjiang.[178] A census of Xinjiang under Qing rule in the early 19th century tabulated ethnic shares of the population as 30% Han and 60% Turkic and it dramatically shifted to 6% Han and 75% Uyghur in the 1953 census. However, a situation similar to the Qing era's demographics with a large number of Han had been restored by 2000, with 40.57% Han and 45.21% Uyghur.[179] Professor Stanley W. Toops noted that today's demographic situation is similar to that of the early Qing period in Xinjiang.[180] Before 1831, only a few hundred Chinese merchants lived in Southern Xinjiang oases (Tarim Basin), and only a few Uyghurs lived in Northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria).[181] After 1831, the Qing encouraged Han Chinese migration into the Tarim Basin, in southern Xinjiang, but with very little success, and permanent troops were stationed on the land there as well.[182] Political killings and expulsions of non-Uyghur populations during the uprisings in the 1860s[182] and the 1930s saw them experience a sharp decline as a percentage of the total population[183] though they rose once again in the periods of stability from 1880, which saw Xinjiang increase its population from 1.2 million,[184][185] to 1949. From a low of 7% in 1953, the Han began to return to Xinjiang between then and 1964, where they comprised 33% of the population (54% Uyghur), like in Qing times. A decade later, at the beginning of the Chinese economic reform in 1978, the demographic balance was 46% Uyghur and 40% Han,[179] which has not did not change drastically until the last census, in 2000, when the Uyghur population had reduced to 42%.[186] Military personnel are not counted and national minorities are undercounted in the Chinese census, as in most other censuses.[187] While some of the shift has been attributed to an increased Han presence,[11] Uyghurs have also emigrated to other parts of China, where their numbers have increased steadily. Uyghur independence activists express concern over the Han population changing the Uyghur character of the region though the Han and Hui Chinese mostly live in Northern Xinjiang Dzungaria and are separated from areas of historic Uyghur dominance south of the Tian Shan mountains (Southwestern Xinjiang), where Uyghurs account for about 90% of the population.[188]

In general, Uyghurs are the majority in Southwestern Xinjiang, including the prefectures of Kashgar, Khotan, Kizilsu and Aksu (about 80% of Xinjiang's Uyghurs live in those four prefectures) as well as Turpan Prefecture, in Eastern Xinjiang. The Han are the majority in Eastern and Northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria), including the cities of Ürümqi, Karamay, Shihezi and the prefectures of Changjyi, Bortala, Bayin'gholin, Ili (especially the cities of Kuitun) and Kumul. Kazakhs are mostly concentrated in Ili Prefecture in Northern Xinjiang. Kazakhs are the majority in the northernmost part of Xinjiang.

| Ethnic groups in Xinjiang 根据2015年底人口抽查统计 [189] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Population | Percentage |

| Uyghur | 11,303,300 | 46.42% |

| Han | 8,611,000 | 38.99% |

| Kazakh | 1,591,200 | 7.02% |

| Hui | 1,015,800 | 4.54% |

| Kirghiz | 202,200 | 0.88% |

| Mongols | 180,600 | 0.83% |

| Tajiks | 50,100 | 0.21% |

| Xibe | 43,200 | 0.20% |

| Manchu | 27,515 | 0.11% |

| Tujia | 15,787 | 0.086% |

| Uzbek | 18,769 | 0.066% |

| Russian | 11,800 | 0.048% |

| Miao | 7,006 | 0.038% |

| Tibetan | 6,153 | 0.033% |

| Zhuang | 5,642 | 0.031% |

| Tatar | 5,183 | 0.024% |

| Salar | 3,762 | 0.020% |

| Other | 129,190 | 0.600% |

| Major ethnic groups in Xinjiang by region (2000 census)[upper-roman 1] P = Prefecture; AP = Autonomous prefecture; PLC = Prefecture-level city; DACLC = Directly administered county-level city.[190] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uyghurs (%) | Han (%) | Kazakhs (%) | others (%) | |

| Xinjiang | 43.6 | 40.6 | 8.3 | 7.5 |

| Ürümqi PLC | 11.8 | 75.3 | 3.3 | 9.6 |

| Karamay PLC | 13.8 | 78.1 | 3.7 | 4.5 |

| Turpan Prefecture | 70.0 | 23.3 | < 0.1 | 6.6 |

| Kumul Prefecture | 18.4 | 68.9 | 8.8 | 3.9 |

| Changji AP + Wujiaqu DACLC | 3.9 | 75.1 | 8.0 | 13.0 |

| Bortala AP | 12.5 | 67.2 | 9.1 | 11.1 |

| Bayin'gholin AP | 32.7 | 57.5 | < 0.1 | 9.7 |

| Aksu Prefecture + Aral DACLC | 71.8 | 26.6 | 0.1 | 1.4 |

| Kizilsu AP | 64.0 | 6.4 | < 0.1 | 29.6 |

| Kashgar Prefecture + Tumushuke DACLC | 89.3 | 9.2 | < 0.1 | 1.5 |

| Khotan Prefecture | 96.4 | 3.3 | < 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Ili AP[note 2] | 16.1 | 44.4 | 25.6 | 13.9 |

| – Kuitun DACLC | 0.5 | 94.6 | 1.8 | 3.1 |

| – former Ili Prefecture | 27.2 | 32.4 | 22.6 | 17.8 |

| – Tacheng Prefecture | 4.1 | 58.6 | 24.2 | 13.1 |

| – Altay Prefecture | 1.8 | 40.9 | 51.4 | 5.9 |

| Shihezi DACLC | 1.2 | 94.5 | 0.6 | 3.7 |

- Does not include members of the People's Liberation Army in active service.

Vital statistics

| Year[191] | Population | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1000) |

Crude death rate (per 1000) |

Natural change (per 1000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 22,090,000 | 14.99 | 4.42 | 10.57 | |||

| 2012 | 22,330,000 | 15.32 | 4.48 | 10.84 | |||

| 2013 | 22,640,000 | 15.84 | 4.92 | 10.92 | |||

| 2014 | 22,980,000 | 16.44 | 4.97 | 11.47 | |||

| 2015 | 23,600,000 | 15.59 | 4.51 | 11.08 | |||

| 2016 | 23,980,000 | 15.34 | 4.26 | 11.08 | |||

| 2017 | 24,450,000 | 15.88 | 4.48 | 11.40 | |||

| 2018 | 24,870,000 | 10.69 | 4.56 | 6.13 |

Religion

Religion in Xinjiang (around 2010)

The major religions in Xinjiang are Islam among the Uyghurs and the Hui Chinese minority and many of the Han Chinese practice Chinese folk religions, Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism. According to a demographic analysis of the year 2010, Muslims form 58% of the province's population.[192] In 1950, there were 29,000 mosques and 54,000 imams in Xinjiang, which fell to 14,000 mosques and 29,000 imams by 1966. Following the Cultural Revolution, there were only about 1,400 remaining mosques. By the mid-1980's, the number of mosques had returned to 1950 levels.[194] According to a 2020 report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, since 2017, Chinese authorities have destroyed or damaged 16,000 mosques in Xinjiang – 65% of the region's total.[195][196] Christianity in Xinjiang is the religion of 1% of the population according to the Chinese General Social Survey of 2009.[193]

A majority of the Uyghur Muslims adhere to Sunni Islam of the Hanafi school of jurisprudence or madhab. A minority of Shias, almost exclusively of the Nizari Ismaili (Seveners) rites are located in the higher mountains of Tajik and Tian Shan. In the western mountains (the Tajiks), almost the entire population of Tajiks (Sarikolis and Wakhis), are Nizari Ismaili Shia.[11] In the north, in the Tian Shan, the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz are Sunni.

Afaq Khoja Mausoleum and Id Kah Mosque in Kashgar are most important Islamic Xinjiang sites. Emin Minaret in Turfan is a key Islamic site. Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves is a noticeable Buddhist site.

"Heroic Gesture of Bodhisattvathe Bodhisattva", example of 6th-7th-century terracotta Greco-Buddhist art (local populations were Buddhist) from Tumxuk, Xinjiang

"Heroic Gesture of Bodhisattvathe Bodhisattva", example of 6th-7th-century terracotta Greco-Buddhist art (local populations were Buddhist) from Tumxuk, Xinjiang

A mosque in Ürümqi

A mosque in Ürümqi

.jpg.webp) Temple of the Great Buddha in Midong, Ürümqi

Temple of the Great Buddha in Midong, Ürümqi_Taoist_Temple_at_Tianchi_(Heavenly_Lake)_in_Fukang%252C_Changji%252C_Xinjiang.jpg.webp) Taoist Temple of Fortune and Longevity at the Heavenly Lake of Tianshan in Fukang, Changji Hui Autonomous Prefecture

Taoist Temple of Fortune and Longevity at the Heavenly Lake of Tianshan in Fukang, Changji Hui Autonomous Prefecture.jpg.webp)

Id Kah mosque in Kashgar, largest mosque in China

Id Kah mosque in Kashgar, largest mosque in China

Sports

Xinjiang is home to the Xinjiang Guanghui Flying Tigers professional basketball team of the Chinese Basketball Association, and to Xinjiang Tianshan Leopard F.C., a football team that plays in China League One.

The capital, Ürümqi, is home to the Xinjiang University baseball team, an integrated Uyghur and Han group profiled in the documentary film Diamond in the Dunes.

Transportation

Roads

In 2008, according to the Xinjiang Transportation Network Plan, the government has focused construction on State Road 314, Alar-Hotan Desert Highway, State Road 218, Qingshui River Line-Yining Highway and State Road 217, as well as other roads.

The construction of the first expressway in the mountainous area of Xinjiang began a new stage in its construction on 24 July 2007. The 56 km (35 mi) highway linking Sayram Lake and Guozi Valley in Northern Xinjiang area had cost 2.39 billion yuan. The expressway is designed to improve the speed of national highway 312 in northern Xinjiang. The project started in August 2006 and several stages have been fully operational since March 2007. Over 3,000 construction workers have been involved. The 700 m-long Guozi Valley Cable Bridge over the expressway is now currently being constructed, with the 24 main pile foundations already completed. Highway 312 national highway Xinjiang section, connects Xinjiang with China's east coast, Central and West Asia, plus some parts of Europe. It is a key factor in Xinjiang's economic development. The population it covers is around 40% of the overall in Xinjiang, who contribute half of the GDP in the area.

The head of the Transport Department was quoted as saying that 24,800,000,000 RMB had been invested into Xinjiang's road network in 2010 alone and, by this time, the roads covered approximately 152,000 km (94,000 mi).[197]

Rail

Xinjiang's rail hub is Ürümqi. To the east, a conventional and a high-speed rail line runs through Turpan and Hami to Lanzhou in Gansu Province. A third outlet to the east connects Hami and Inner Mongolia.

To the west, the Northern Xinjiang runs along the northern footslopes of the Tian Shan range through Changji, Shihezi, Kuytun and Jinghe to the Kazakh border at Alashankou, where it links up with the Turkestan–Siberia Railway. Together, the Northern Xinjiang and the Lanzhou-Xinjiang lines form part of the Trans-Eurasian Continental Railway, which extends from Rotterdam, on the North Sea, to Lianyungang, on the East China Sea. The Second Ürümqi-Jinghe Railway provides additional rail transport capacity to Jinghe, from which the Jinghe-Yining-Horgos Railway heads into the Ili River Valley to Yining, Huocheng and Khorgos, a second rail border crossing with Kazakhstan. The Kuytun-Beitun Railway runs from Kuytun north into the Junggar Basin to Karamay and Beitun, near Altay.

In the south, the Southern Xinjiang Line from Turpan runs southwest along the southern footslopes of the Tian Shan into the Tarim Basin, with stops at Yanqi, Korla, Kuqa, Aksu, Maralbexi (Bachu), Artux and Kashgar. From Kashgar, the Kashgar–Hotan railway, follows the southern rim of the Tarim to Hotan, with stops at Shule, Akto, Yengisar, Shache (Yarkant), Yecheng (Karghilik), Moyu (Karakax).

The Ürümqi-Dzungaria Railway connects Ürümqi with coal fields in the eastern Junggar Basin. The Hami–Lop Nur Railway connects Hami with potassium salt mines in and around Lop Nur.

The Golmud-Korla Railway, under construction as of August 2016, would provide an outlet to Qinghai. Railways to Pakistan and Kyrgyzstan have been proposed.

East Turkestan independence movement

Some factions in Xinjiang province advocate establishing an independent country, which has led to tension and ethnic strife in the region.[198][199] The Xinjiang conflict[200] is an ongoing[201] separatist conflict in the northwestern part of China. The separatist movement claims that the region, which they view as their homeland and refer to as East Turkestan, is not part of China, but was invaded by China in 1949 and has been under Chinese occupation since then. China asserts that the region has been part of China since ancient times.[202] The separatist movement is led by ethnically Uyghur Muslim underground organizations, most notably the East Turkestan independence movement and the Salafist Turkistan Islamic Party, against the Chinese government. According to the Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, the two main sources for separatism in the Xinjiang Province are religion and ethnicity. Religiously, the Uyghur peoples of Xinjiang follow Islam; in the large cities of Han China many are Buddhist, Taoist and Confucian, although many follow Islam as well, such as the Hui ethnic subgroup of the Han ethnicity, comprising some 10 million people. Thus, the major difference and source of friction with eastern China is ethnicity and religious doctrinal differences that differentiate them politically from other Muslim minorities elsewhere in the country. Because of turkification from the turkificated Tocharians, the western Uyghurs became linguistically and culturally Turkic in the 10th century, a distinction from the Han that are the majority in the eastern regions of China, although many other Turkic ethnicities live in East China such as the Salar people, the Chinese Tatars and the Yugur. Ironically, the capital of Xinjiang, Ürümqi, was originally a Han and Hui (Tungan) city with few Uyghur people before recent Uyghur migration to the city.[203] Since 1996, China has engaged in "strike hard" campaigns targeted at separatists.[204] On 5 June 2014, China sentenced nine people to death for terrorist attacks. They were alleged to be seeking to overthrow Chinese rule in Xinjiang and re-establish an independent Uyghur state of East Turkestan.[205]

See also

Notes