Andrianampoinimerina

Andrianampoinimerinā (Malagasy pronunciation: [anˈɖʐianˌmpuʲnˈmerʲnə̥]) (1745–1810) ruled the Kingdom of Imerina from 1787 until his death. His reign was marked by the reunification of Imerina following 77 years of civil war, and the subsequent expansion of his kingdom into neighboring territories, thereby initiating the unification of Madagascar under Merina rule. Andrianampoinimerina is a cultural hero and holds near mythic status among the Merina people, and is considered one of the greatest military and political leaders in the history of Madagascar.

| Andrianampoinimerina | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

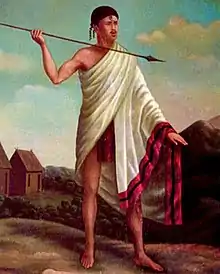

Idealized portrait painted around 1905 by Ramanankirahina | |||||

| King of Imerina | |||||

| Reign | ca. 1787–1810 | ||||

| Predecessor | Andrianjafy | ||||

| Successor | Radama I | ||||

| Born | 1745 Ikaloy | ||||

| Died | 1810 (aged 64–65) Antananarivo | ||||

| Burial | 1810 | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Hova dynasty | ||||

| Father | Andriamiaramanjaka | ||||

| Mother | Princess Ranavalonanandriambelomasina | ||||

Andrianampoinimerina took power upon deposing his uncle, King Andrianjafy, who had ruled over Imerina Avaradrano (Northern Imerina). Prior to Andrianampoinimerina's reign, Imerina Avaradrano had been locked in conflict with the three other neighboring provinces of the former kingdom of Imerina that had last been unified under King Andriamasinavalona a century before. Andrianampoinimerina established his capital at the fortified town of Ambohimanga, a site of great spiritual, cultural and political significance that was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2001. The king's original royal lodgings can still be visited at Ambohimanga today. From this position, he progressively extended his domain first over all Imerina and then over the greater Highlands, absorbing the Betsileo, Sihanaka, Bezanozano and Bara territories. Having reigned for 23 years at the time of his death, Andrianampoinimerina had successfully reunited Imerina and vastly expanded the Merina kingdom, with the intent to ultimately unify all of Madagascar under Merina rule. His son and heir, Radama I, continued the conquests Andrianampoinimerina had begun, and over the next two decades largely achieved his father's vision.

Early life

Birth

Andrianampoinimerina was born Ramboasalamarazaka (short form: Ramboasalama)[1] around 1745 in Ikaloy, in central Madagascar, to Princess Ranavalonandriambelomasina, daughter of King Andriambelomasina of Imerina (1730-1770), and her husband Andriamiaramanjaka, an andriana (noble) of the Zafimamy royal family in the independent kingdom of Alahamadintany to the north of Imerina. His mother's brother Andrianjafy was named Andriambelomasina's successor and was king of Imerina Avaradrano, the northern quadrant of the former Kingdom of Imerina, from 1770 to 1787.[2]

Ramboasalamarazaka was born during a period when conflict and famine afflicted Imerina.[3] For almost a century, from the end of the reign of King Ralambo (1575–1600) to King Andriamasinavalona (1675–1710), the Kingdom of Imerina in Madagascar's central highlands had generally enjoyed prosperity, expansion and civil peace. This stability and the unity of Imerina collapsed after Andriamasinavalona divided the kingdom among his four favorite sons, leading to 77 years of civil war that weakened the ability of subsequent princes to respond effectively to the pressures of slave trading and a growing population.[4] Merina kings had long intended to extend their kingdom to the North by absorbing the Zafimamy kingdom of Alahamadintany, and the Zafimamy kings of Alahamadintany had also wished to extend their land to the South by absorbing the Merina Kingdom. The marriage between Ramboasalamarazaka's parents was a political alliance contracted as part of Andriambelomasina's strategy to mitigate the threat of invasions by the Alahamadintany-Zafimamy alliance to the North. The marriage agreement stipulated that after the reign of Andriambelomasina's son, Andrianjafy, the throne would pass to his daughter's son, Ramboasalamarazaka.[3] The alliance between these two royal families represented a fair and peaceful compromise: the prince born of this union would rule over both states and unify the two kingdoms.[3]

Andrianampoinimerina's Zafimamy ancestors practiced endogamy and therefore rarely mixed with the descendants of the legendary first inhabitants of Madagascar, the Vazimba. However, Ramboasalamarazaka had partial Vazimba ancestry on his mother's side through her antecedent, King Andriamanelo (1540–1575), son of Vazimba Queen Rafohy (1530–1540) and her Merina husband Manelo.[5] He was born during the first quarter of the moon (tsinambolana) of the month Alahamady, the sign of a highly auspicious birth according to popular belief. Following the Merina customs of the time, his parents gave him the humble name Ramboasalama (Ra-amboa-salama, "The healthy dog") to protect him from attracting the undesirable attention of jealous rivals or evil spirits, before being changed in childhood to Ramboasalamarazaka.[2]

Childhood and education

Ramboasalamarazaka spent his early childhood in his father's Zafimamy court at Ikaloy.[2] There he received a traditional education, including mastery of fanorona, a local board game believed to develop intelligence and the ability to think strategically.[6] Young nobles being groomed for leadership roles typically learned to perform kabary (a stylized form of public address), including the judicious use of ohabolana (proverbs) to persuasively make a point.[7] Young Merina princes also often learned to play the valiha, a bamboo tube zither then reserved for Merina and Zafimamy nobles.[8] Around the age of 12, Ramboasalamarazaka continued his education under the supervision of his grandfather, King Andriambelomasina, at Amboatany and the royal court in Ambohimanga.[2]

Merchant

As a young man, Ramboasalamarazaka worked as a merchant and may have also traded in slaves.[2] During this period he gained a reputation as a champion of the commoner, committed to defending them against raids by Sakalava warriors and slave traders and fighting against corruption.[2] Regarded as a self-made man who did not rely on his privileges as a prince, his independence, temperament, tenacity and sense of justice made him popular among the commoners and the slaves of Ambohimanga. His popularity stood in contrast to public discontentment with his uncle, King Andrianjafy, who was viewed as a despotic and incompetent ruler.[9] Ramboasalamarazaka frequently made promises to the populace regarding his future reign, which led Andrianjafy perceived as a threat to his authority, leading him to execute citizens of his territory who engaged his nephew in such promises; contrary to his intentions, this response only served to turn popular opinion against Andrianjafy.[10]

Conflict with Andrianjafy

Although Andrianjafy may have initially intended for Ramboasalamarazaka to succeed him, this appears to have changed following the birth of his son, whom his wife persuaded him to name as successor in disregard of his father's earlier decree.[11] Andrianjafy consequently made several attempts to have his nephew killed, but on each occasion Ramboasalamarazaka was warned by Andrianjafy's brother and managed to avert the plot.[12] In 1787, when Ramboasalamarazaka was 42 years old, the conflict between the men reached a turning point:[13] Andrianjafy decided to send a group of assassins to Ramboasalama's residence in Ambohimanga. Andrianjafy's brother again took action and warned Ramboasalamarazaka to flee, but rather than leave Ambohimanga, Ramboasalama followed the advice of an elder who instructed him to sacrifice a ram to invoke ancestral protection. The elder then gathered the twelve most respected men of Ambohimanga and thirty soldiers, and rallied them to enforce the decree of Andriambelomasina by overthrowing Andrianjafy and swearing allegiance to Ramboasalama.[14] After the success of the coup, the new king adopted his ruling name, Andrianampoinimerina.[13] The support of the Tsimahafotsy, inhabitants of Ambohimanga, ensured the defense of the city against efforts by Andrianjafy to reclaim his capital and his authority.[14]

Andrianjafy rallied the people of his home village of Ilafy to fight against those of Ambohimanga. Both sides were armed with spears and firearms. An initial battle at Marintampona saw the Ilafy army defeated. Both sides regrouped for a second confrontation at Amboniloha, which took place at night and did not end in a definitive win for either side. In the morning, Andrianjafy moved his army north of Anosy and the two sides clashed again in a battle that lasted two days. The Ilafy army lost the skirmish and retreated to their village. After losing these battles, the residents of Ilafy decided to submit to Andrianampoinimerina. To rid themselves of Andrianjafy, the people encouraged him to travel to Antananarivo and Alasora to seek allies in the defense of their town. Once he had departed, the villagers barred the town gates and announced their desire to enforce the decree of Andriambelomasina. Seeking support to recapture the throne, Andrianjafy traveled to Antananarivo, Ambohipeto, Alasora and Anosizato to secure an alliance, but each time he was rebuffed.[15] The conflict came to an end in 1787 when Andrianampoinimerina exiled his uncle; varying sources report that shortly afterward Andrianjafy either died in exile or was killed by Andrianampoinimerina's followers.[16]

Reign and expansion of territory

Reunification of historic Imerina

Continuing his conquests in the 1790s, Andrianampoinimerina began establishing control over a comparatively large part of the highlands of Madagascar including the twelve sacred hills of Imerina. Andrianampoinimerina conquered Antananarivo in 1793[13] and concluded treaties with the kings of Antananarivo and Ambohidratrimo.[1] He shifted the kingdom's political capital back to Antananarivo in 1794.[17] By 1795 he had gained the allegiance and submission of all the territories that had formed Imerina at its largest extent under Andriamasinavalona, effectively achieving the reunification of Imerina.[18] The former kings of Antananarivo and Ambohidratrimo periodically engaged in resistance against his authority in disregard of the treaties they had concluded, prompting Andrianampoinimerina to launch renewed campaigns to eliminate both kings;[1] the re-pacification of Antananarivo began in 1794[19] and achieved definitive success in 1797, with Ambohidratrimo reconquered shortly afterward.[4] By 1800, he had absorbed several other previously independent sections of Imerina into his kingdom.[4] He reinforced alliances with powerful nobles in conquered regions of Imerina through marriage to local princesses, and is said to have wed 12 women in total. He placed each wife at a house built at each of the twelve sacred hills.[21] After the political capital of Imerina was shifted back to Antananarivo, Andrianampoinimerina declared Ambohimanga to be the spiritual capital of Imerina.[22]

Conquest of greater Madagascar

The latter half of Andrianampoinimerina's reign from around 1800 was marked by an effort to unite the island's 18 ethnic groups under his rule.[1] This effort began with the sending of royal messengers bearing invitations to become vassal states under Andrianampoinimerina's sovereignty, or face a military conquest.[4] The first focus of this expansion was territory that had historically been inhabited by the Merina people but had come under the rule of other groups, particularly including the eastern lands held by the Sihanaka and Bezanozano peoples. Andrianampoinimerina then consolidated Merina power in neighboring southern central Betsileo territories, establishing military outposts to protect Merina settlers as far south as the Ankaratra mountains and Faratsiho.[23] Kingdoms that united with Imerina as a result of diplomatic efforts included the Betsileo around Manandriana; the Betsileo, Merina and Antandrano Andrandtsay of Betafo; and the western region of Imamo. The Sakalava of Menabe and Manangina rejected these offers and actively resisted Merina domination;[4] the Bezanozano territories likewise resisted, although the Merina managed to preserve a tenuous hold over the area.[23]

The gradual conquest of surrounding lands by Andrianampoinimerina and his Merina army was vigorously opposed by the Sakalava, who remained a major threat to Andrianampoinimerina and his people.[2] Throughout his reign, bands of Sakalava mounted slave raids in Imerina and brought captured Merina to the coast for sale to European slave traders. Sakalava armies mounted repeated incursions into Imerina and nearly breached the capital city on more than one occasion. Andrianampoinimerina launched several campaigns to pacify the Sakalava but none were successful. He also sought to establish peace through marriages intended to form political alliances, but without achieving lasting peace or an end to the slave raids.[23]

Certain Merina nobles and several members of the royal family also posed a threat to Andrianampoinimerina's rule. After deposing Andrianjafy, the fallen king made an attempt on Andrianampoinimerina's life. This assassination attempt was foiled by an informant who had learned about the conspiracy by chance. Andrianampoinimerina rewarded the informant by marrying his daughter to his son, future King Radama I. Andrianampoinimerina furthermore declared that any child from this union would be first in the line of succession after Radama. The marriage did not produce children, however, and following Radama's death in 1828, this royal wife would rule Madagascar for 33 years as Queen Ranavalona I.[24] Andrianaimpoinimerina's authority was also threatened by his adopted son, Rabodolahy, who plotted to kill Radama; when these efforts failed, he attempted to assassinate Andrianampoinimerina, but was discovered and executed.[25]

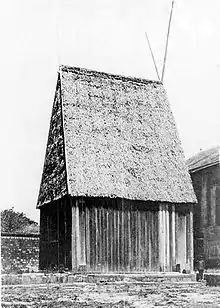

Governance of the Kingdom of Imerina

Beginning in 1797, Andrianampoinimerina ruled his expanding kingdom from Antananarivo, the traditional capital of the Kingdom of Imerina. He is credited with major development and reorganization of the city.[26] His vision for the capital was to serve as a microcosm of his kingdom and a model of urban planning that would be replicated in each new territory. In keeping with sacred Merina symbolism associated with height, space and cardinal orientation, he retained the royal compound - the Rova of Antananarivo - at the crest of the highest hill in the city, and in the center of the urban space that expanded around it.[26] He also undertook significant expansion of the sacred rova compound and improved its venerable buildings. This included the reconstruction in 1800 of Besakana, the "throne of the kingdom"[27] built by king Andrianjaka in the early 1600s as the first royal residence at Antananarivo[28] - one of several houses used as residences by Andrianampoinimerina at the palace, the other principal residence being Mahitsielafanjaka after he moved his capital from Ambohimanga to Antananarivo.[29] He implanted representatives of ethnic groups he had recently conquered in specified neighborhoods of the city.[30] Each Merina social class had its designated districts: slaves lived south of the rova (a disfavored direction in Merina cosmology), the mainty (royal servant class) lived to the southeast in Amparihy, important hova clans were allotted the district to the west of the royal compound, and each of the seven sub-classes of andriana nobles were assigned to a district to the sacred north and northeast of the palace. Within this broad district structure, each clan (foko) was assigned a specific neighborhood in an orientation roughly corresponding to the orientation of their home village vis-a-vis the capital city.[31] In the popular imagination of the residents of modern-day Antananarivo, the city in the time of Andrianampoinimerina is envisioned as a perfect and harmonious urban space embodying the best of Merina ingenuity and spiritual significance.[32]

The legitimacy of Andrianampoinimerina's reign was bolstered by his characterization of other Merina rulers' claims to power as fanjakana hova - rule by hova (commoners), whose lineages were only weakly tied to the line of succession relative to his own. In addition, like Merina kings before him, he consolidated the power of the sampy (royal idols) and attributed the success and legitimacy of his reign to the proper respect shown toward these conduits of supernatural power.[2] He balanced this strengthening of the supernatural and ancestral legitimacy of his kingship against inclusiveness of the commoner class by making several hova from the Tsimiamboholahy and Tsimahafotsy clans into powerful and trusted advisers.[33] He also consulted a group of ombiasy (royal advisers of the Antaimoro clan), who were literate in the sorabe script historically used on the east coast to inscribe a series of ancient texts considered to contain powerful magic and specialized scientific and ritual knowledge.[34]

The population of Imerina was governed through a mixture of traditional practices and innovative measures. While all land technically belonged to the sovereign, its administration was carried out by andriana who were assigned a menakely (subdivision of land) to govern. These administrators were themselves overseen by roving royal advisers. The land was cultivated by commoners, who were given a parcel to farm based on the size of the family it was meant to feed, and each family paid taxes to the king in return. Andrianampoinimerina passed laws giving children the right to claim meat from the butcher that had not been sold by the day's end, and allowing the poor to eat cassava from others' fields, provided they took only what they could cook and consume on the spot. In this way, the basic nutritional needs of most citizens were met.[35]

Social organization

The hierarchy of Merina andriana sub-classes established in the 16th century under Andriamanelo was revised by Andrianampoinimerina, as it had been done by Andriamasinavalona.[36] He decreed new rights and responsibilities for the andriana, including the privilege of placing sculptures or images of the voromahery (black kite) on their homes to indicate their noble status.[37]

In order to strengthen relationships within clans and communities, and to promote moderation and equitable distribution of resources, Andrianampoinimerina decreed that families should build larger, monolithic stone tombs to hold the remains of all family members, and that the construction of these tombs was to be undertaken as a shared responsibility among members of the family to be entombed there.[18]

Modifications and expansions on several traditional royal rituals under Andrianampoinimerina enabled him to develop a state religion in which he was the central figure. The tradition of the fandroana festival established by the 17th century Merina king Ralambo was made a much larger event intended to symbolically renew the nation and the cosmic power that legitimized and strengthened Andrianampoinimerina's reign as well as the power of the state.[38] This served to further unify his citizens while legitimizing and strengthening his rule.[39]

Public works

The long-established royal Merina tradition of fanompoana (labor as a form of tax) was continued and expanded under Andrianampoinimerina. Major public works were carried out under his reign, including the further expansion of irrigated paddy fields in the Betsimitatatra plains surrounding Antananarivo. He devised systems for organizing work teams, motivated their efforts by setting up competitions between teams, and punished those who failed to contribute their due share of effort.[35] He mobilized groups of hiragasy village musicians to entertain work teams and later employed them to travel among towns and villages across the kingdom, broadcasting news, announcing new laws and promoting proper social behavior.[40]

Laws

Andrianampoinimerina developed a legal system that applied throughout the territories he ruled. He was the first Merina king to establish formal civil and penal codes, the latter ameliorated and transcribed by his son Radama. He declared twelve crimes to be capital offenses, while many others entailed collective punishment for the guilty party and his or her family members including forced labor in chains and being reduced to slave status. These harsh penalties were intended to act as a strong disincentive to engage in antisocial acts; the consumption of alcohol, marijuana and tobacco were also outlawed, although they remained prevalent. To judge infractions of his laws, the king often relied on the tradition of tangena, whereby surviving the ingestion of poison indicated an accused person's innocence.[35]

Economy

.jpg.webp)

Under Andrianampoinimerina, regulations were established to manage trading in slaves and other commodities. Estimates put the number of slaves traded by the king at around 1,800 per year, mainly in exchange for firearms and principally to French merchants who sold them on to Mauritius and Reunion. This brought order to the kingdom's economy, enriched the crown, and enabled the king to monopolize trade in certain particularly lucrative goods, thereby weakening opportunities for political rivals to amass enough wealth and influence to unseat him. While this soured his relationship with certain andriana, it increased his popularity among the commoner and slave classes. His practice of commonly deciding in favor of commoners in disputes with nobles further strengthened his image as a fair ruler.[2]

Andrianampoinimerina regulated commerce and the economy by creating official markets (tsena) and standardizing market scales (fandanjana) and other units of measurement, including length and volume.[35] King Andrianampoinimerina established the first marketplace in Antananarivo[19] on the grounds today occupied by the Analakely market's tile-roofed pavilions, constructed in the 1930s.[41] Andrianampoinimerina decreed Friday (Zoma) as market day,[19] when merchants would come to Analakely to erect stalls shaded with traditional white parasols. This sea of parasols extended throughout the valley, forming what has been called the largest open air marketplace in the world.[42] Traffic congestion and safety hazards caused by the ever-growing Zoma market prompted government officials to split up and relocate the Friday merchants to several other districts in 1997.[43] Prosperity for the masses in Imerina increased throughout Andrianampoinimerina's reign, leading to growth in population density.[35]

Military organization

Finally, he established a citizen army called the foloalindahy (the "100,000 soldiers"). Men fit for military service were recruited to engage in Andrianampoinimerina's campaigns of conquest between periods designated for public works projects. These campaigns served to enrich Imerina by capturing slaves for labor and service to the Merina andriana and hova classes, or for sale or trade to coastal communities in exchange for firearms.[35] His military was equipped with the sizeable stock of arms he procured from coastal traders in western Madagascar.[4]

Death and succession

Andrianampoinimerina died in the Mahitsielafanjaka house on the compound of the Rova of Antananarivo on 6 July 1810 at the age of 65, having fathered eleven sons and thirteen daughters by his many wives. In the Vazimba tradition of Merina kings before him, the body of Andrianampoinimerina was placed in a canoe made of silver (rather than the customary hollowed out log)[44] and interred in one of the royal tranomasina tombs at Ambohimanga. Shortly after the French established a colonial presence on the island in 1896, they destroyed Andrianampoinimerina's original tomb in March 1897,[45] removed his remains, and relocated them to the rova of Antananarivo where they were interred in the tomb of his son.[46] This was done in an effort to desanctify the city of Ambohimanga, break the spirit of the Menalamba resistance fighters who had been rebelling against French colonization for the past year,[45] weaken popular belief in the power of the royal ancestors, and relegate Malagasy sovereignty under the Merina rulers to a relic of an unenlightened past.[28] Andrianampoinimerina was succeeded by his 18-year-old son, Radama I.[47] In order to fulfill his oath that the child of his son Radama would follow in the line of succession, Andrianampoinimerina had his oldest son, Ramavolahy, killed to prevent any contest for the throne.[48]

Legacy

— Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. V[35]

Historian Bethwell Ogot states Andrianampoinimerina is "regarded as the most important of Imerina's kings".[4] Historian Catherine Fournet-Guérin notes he is an "object of great admiration in the popular imagination."[19] A French trader who had conducted business with him declared in 1808, "He is without doubt the richest, the most feared, the most enlightened, and has the largest kingdom, of all the kings of Madagascar." Malagasy textbooks characterize him as a hero and the originator of the notion of a unified Malagasy national identity.[49]

The primary source of information about the reign of Andrianampoinimerina is Tantara ny Andriana eto Madagasikara, a Malagasy language book relating the oral history of the Merina kings as collected by a Jesuit missionary, Francois Callet, in the late 19th century. Prior to the eventual release of a French language translation in the 1950s, references to the king in academic and popular writing during the colonial period de-emphasized his role as a conduit of traditional religious power and authority, instead glorifying his administrative practices in an attempt to bring greater credibility to the colonial government as a vehicle for building upon and strengthening the principles of good governance that he introduced.[50] Beginning in the 1970s, historians began to focus more on the spiritual aspects of his role as king, and researchers questioned and compared sources in an effort to arrive at a more factual and balanced history of Andrianampoinimerina and his reign.[51]

Innovations during the reign of Andrianampoinimerina were to have long-standing consequences for the structure of Malagasy society in the 19th century. Madagascar specialist Francoise Raison-Jourde attributes the widespread conversions of the masses following the conversion to Christianity of Ranavalona II in 1869 to the precedent established by Andrianampoinimerina of a state religion in which the sovereign is the head and the people are expected to follow.[52] Similarly, Andrianampoinimerina's decision to empower the hova and the two families of advisers in particular led over the next fifty years to the strengthening of the hova middle class that formed the backbone of the merchant, craftsman, farming and administrative cadres. By the reign of Radama II, hova power rivaled and ultimately exceeded the power of the nobles, leading to the aristocratic coup d'etat that ended Radama's reign and the absolute power of the monarch, and established a joint system of government in which the hova Prime Minister and his cabinet governed while the sovereign was reduced to a symbolic figurehead of ancestral power and authority.[33] Ambohimanga, which Andrianampoinimerina declared the spiritual capital of Madagascar, remains among the country's most important spiritual and cultural sites, and was recognized as Madagascar's only cultural UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2001.[53] A major street in Antananarivo, running parallel to the Avenue de l'Independence and one block east, is named after him.[54]

References

- Ade Ajayi 1998, p. 413.

- Rich 2012, pp. 229-230.

- Callet 1908, p. 49.

- Ogot 1992, p. 877.

- Raison-Jourde 1983, p. 182.

- Rabedaoro 2010, p. 11.

- Domenichini-Ramiaramanana 1983, p. 499.

- Schmidhoffer, August. "Some Remarks on the Austronesian Background of Malagasy music" (PDF). Working Paper.

- Callet 1908, pp. 80-86.

- Callet 1908, p. 70.

- Callet 1908, pp. 75, 79.

- Callet 1908, p. 75.

- Berg, Gerald M. (1988). "Sacred Acquisition: Andrianampoinimerina at Ambohimanga, 1777-1790". The Journal of African History. 29 (2): 191–211. doi:10.1017/S002185370002363X. JSTOR 182380.

- Callet 1908, pp. 76-77.

- Callet 1908, pp. 84-86.

- Callet 1908, pp. 87-88.

- "Royal Hill of Ambohimanga". UNESCO. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- Raison-Jourde 2012, p. 204.

- Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 34.

- Van Zant 2013, p. 289.

- Campbell 2012, p. 454.

- Ade Ajayi 1998, p. 415.

- Freeman & Johns 1840, pp. 7-17.

- Callet 1908, pp. 523-30.

- Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 31.

- Featherman 1888, p. 332.

- Frémigacci 1999, pp. 421–444.

- Ranaivo & Janicot 1968, pp. 131–133.

- Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 35.

- Fournet-Guérin 2007, pp. 37-38.

- Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 39.

- Ade Ajayi 1998, p. 423.

- Blanchy et al. 2006, p. 387.

- Fage, Flint & Oliver 1986, p. 400.

- Galibert 2009, p. 439.

- Galibert 2009, p. 473.

- Raison-Jourde 2012, pp. 205-206.

- Raison-Jourde 2012, p. 209.

- Raveloson, Ranja (2012). "Hira Gasy: Musical Theatre in Madagascar". Goethe Institute. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 297.

- Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 312.

- Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 79.

- Galibert 2009, p. 207.

- Ellis & Rajaonah 1998, p. 190.

- Frémigacci 1999, p. 427.

- Ade Ajayi 1998, p. 165.

- Campbell 2012, p. 51.

- Galibert 2009, p. 463.

- Raison-Jourde 2012, p. 202.

- Raison-Jourde 2012, p. 203.

- Raison-Jourde 2012, p. 210.

- "Royal Hill of Ambohimanga". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2012. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- Galibert 2009, p. 186.

Bibliography

- Ade Ajayi, Jacob F. (1998). General history of Africa: Africa in the nineteenth century until the 1880s. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 9780520067011.

- Blanchy, Sophie; Rakotoarisoa, Jean-Aimé; Beaujard, Philippe; Radimilahy, Chantal (2006). Les dieux au service du peuple. Itinéraires religieux, médiations, syncrétisme à Madagascar (in French). Paris: Karthala Editions. ISBN 9782811140465.

- Callet, François (1908). Tantara ny andriana eto Madagasikara (histoire des rois) (in French). Antananarivo: Imprimerie Catholique.

- Campbell, Gwyn (2012). David Griffiths and the Missionary "History of Madagascar". Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-20980-0.

- Domenichini-Ramiaramanana, Bakoly (1983). Du ohabolana au hainteny: langue, littérature et politique à Madagascar. Paris: KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 9782865370634.

- Ellis, Stephen; Rajaonah, Faranirina (1998). L'insurrection des menalamba: une révolte à Madagascar, 1895–1898 (in French). Paris: Karthala Editions. ISBN 978-2-86537-796-1.

- Fage, J.D.; Flint, J.E.; Oliver, R.A. (1986). The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1790 to c. 1870. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20413-5.

- Featherman, Americus (1888). Social history of the races of mankind: Volume 2, Part 2. London: Trübner & Co.

- Fournet-Guérin, Catherine (2007). Vivre à Tananarive: géographie du changement dans la capitale malgache (in French). Antananarivo, Madagascar: Karthala Editions. ISBN 978-2-84586-869-4.

- Freeman, Joseph John; Johns, David (1840). A narrative of the persecution of the Christians in Madagascar: with details of the escape of six Christian refugees now in England. Berlin: J. Snow.

- Frémigacci, Jean (1999). "Le Rova de Tananarive: Destruction d'un lieu saint ou constitution d'une référence identitaire?". In Chrétien, Jean-Pierre (ed.). Histoire d'Afrique (in French). Paris: Éditions Karthala.

- Galibert, Didier (2009). Les gens du pouvoir à Madagascar – Etat postcolonial, légitimités et territoire (1956–2002) (in French). Antananarivo: Karthala Editions. ISBN 9782811131432.

- Nave, Ari (2010). "Andrianampoinimerina". In Appiah, A. and H.L. Gates (ed.). Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 2. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195337709.

- Ogot, Bethwell (1992). Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-101711-7.

- Rabedaoro, Eris (2010). Fanorona (in French). Paris: Publibook. ISBN 9782748355871.

- Raison-Jourde, Françoise (1983). Les souverains de Madagascar (in French). Paris: Karthala Editions. ISBN 978-2-86537-059-7.

- Raison-Jourde, Françoise (2012). "Andrianampoinimerina et la tentative d'autonomisation de l'état Merina. Madagascar XVIIIe siecle". In Chrétien, Jean-Pierre (ed.). L'invention religieuse en Afrique: histoire et religion en Afrique noire (in French). Karthala Editions. pp. 201–212. ISBN 9782865373734.

- Ranaivo, Flavien; Janicot, Claude (1968). Les guides bleues: Madagascar (in French). Paris: Librairie Hachette.

- Rich, Jeremy (2012). "Andrianampoinimerina". In Akyeampong, EK and HL Gates (ed.). Dictionary of African Biography. Oxford University Press. pp. 229–230. ISBN 9780195382075.

- Van Zant, Peter (2013). New Developments In Asian Studies. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781136174704.