Radama I

Radama I "the Great" (1793–1828) was the first Malagasy sovereign to be recognized as King of Madagascar (1810–1828) by a European state. He came to power at the age of 18 following the death of his father, King Andrianampoinimerina. Under Radama's rule and at his invitation, the first Europeans entered his central highland Kingdom of Imerina and its capital at Antananarivo. Radama encouraged these London Missionary Society envoys to establish schools to teach tradecraft and literacy to nobles and potential military and civil service recruits; they also introduced Christianity and taught literacy using the translated Bible. A wide range of political and social reforms were enacted under his rule, including an end to the international slave trade, which had historically been a key source of wealth and armaments for the Merina monarchy. Through aggressive military campaigns he successfully united two-thirds of the island under his rule. Abuse of alcohol weakened his health and he died prematurely at age 35. He was succeeded by his highest-ranking wife, Ranavalona I.

| Radama I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| King of Madagascar | |||||

| Reign | 1810 – 27 July 1828 | ||||

| Coronation | 1810 | ||||

| Predecessor | Andrianampoinimerina | ||||

| Successor | Ranavalona I | ||||

| Born | c. 1793 Ambohimanga, Madagascar | ||||

| Died | 27 July 1828 (age 35) Rova of Antananarivo | ||||

| Burial | c. 1828 Tomb of Radama I, Rova of Antananarivo | ||||

| Spouse | Ramavo | ||||

| |||||

| Father | Andrianampoinimerina | ||||

| Mother | Rambolamasoandro | ||||

Early years

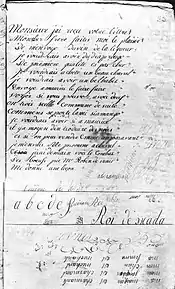

Radama was the son of Rambolamasoandro[2] and King Andrianampoinimerina of Imerina, a growing kingdom in the central plateau of the island around Antananarivo.[3] As a child, Radama was educated at court and learned to read the Malagasy language in the Sorabe Arabico-Malagasy script used by Antemoro ombiasy (court astrologers).[4] As a young man he was described by a contemporary as about 5'4" (1.6 meters) and slim with broad shoulders and a narrow waist.[5]

Radama was invited to join his father on a military expedition during his campaign to pacify the Betsileo, who had forsaken an oath sworn to Andrianampoinimerina. Their initial attempt to capture King Andriamanalina at the fortified city of Fandanana west of Antsirabe was unsuccessful. When they returned a year later, Andrianampoinimerina split his army into two columns and put Radama at the head of the second column, providing him with his first opportunity to command a military regiment. He was accompanied by a group of seasoned soldiers called the Tantsaha, and Andriandtsoanandria, one of his father's more experienced military advisers, and successfully negotiated the submission of several towns in Betsileo. Andrianampoinimerina ultimately captured and executed Andriamanalina, and together Radama and his father also captured the strategic town of Kiririoka.[6] On Andrianampoinimerina's deathbed, he reportedly told his son, "The sea is the border of my rice field".[7] Radama swore to his father that he would achieve this ambition.[8]

Reign

In 1810, at the age of 18, Radama succeeded his father as king of Imerina.[3] Several of the principalities conquered by his father revolted upon news of Andrianampoinimerina's death,[9] immediately obliging the young ruler to embark on military campaigns that successfully put down the rebellions and secured his position, which included completing the pacification of the Betsileo kingdom.[9]

In 1816 Radama was contacted by a Mauritian trader sent by British Governor Robert Townsend Farquhar of Mauritius (Ile de France), who was interested in increasing British influence in the region and preventing the re-establishment of French trading posts on Madagascar; as a result of this initial contact, two of Radama's brothers were sponsored to be educated in England. This was followed by a commercial treaty. On 23 October 1817, Radama signed a treaty negotiated by former military general James Hastie that granted Radama a formal alliance with the British crown and its recognition of Radama as "King of Madagascar" in exchange for horses, uniforms and a pledge to abandon the export of slaves.[9] The British were invited to establish a diplomatic mission on the island, and in 1820 Hastie was appointed to the role of British resident.[3] The import of slaves from the African mainland continued, however, and remained Madagascar's primary import throughout Radama's reign and into the 1850s.[10]

Radama's military campaign to Toamasina in 1820 brought him into contact with Welshmen David Jones and David Griffiths of the Protestant London Missionary Society (LMS), who had established a school there enrolling three students. Radama was inspired to introduce similar schools throughout Imerina and within a year had established 23 schools enrolling 2300 students, of whom a third were girls.[11] He tasked the LMS missionaries to transcribe and teach the Malagasy language using the Latin alphabet.[12] It was under Radama's rule that LMS missionaries (with notable contributions from Scottsman James Cameron) set up craft industries in carpentry, leather, tin plating and cotton, introduced the first printing press, translated and printed Bibles in the Malagasy language[3] and oversaw Radama's plan to establish dozens of schools offering compulsory literacy courses and basic education for the nobles of Imerina.

Radama's European contacts describe him as openly skeptical of many of the religious rituals and traditions that formed the legitimacy of the Merina monarchy over the past four centuries. In particular he was reportedly critical of the importance placed on the sampy, the 12 royal idols that figured prominently in Merina court ritual.[13] Many of the cultural and technological innovations Radama introduced during his reign were rejected by the broader population as a denial of the heritage of their ancestors and their traditions.[14]

During this time and with the help of the British support, Radama's military became the dominant force allowing him to unify the island by force. Radama reportedly admired Napoleon Bonaparte and drew upon European structure and tactics to modernize his army, which included French, British and Jamaican generals.[15] In each newly conquered territory, administrative posts were built within fortified garrisons (rova) on the model of the original Rova of Antananarivo. These were staffed with Merina colonists called voanjo ("peanuts").

Radama's territorial expansion began in 1817 with a campaign to the eastern port town of Toamasina, where he established a military post. This was followed by a series of westward campaigns into Menabe in 1820, 1821 and 1822. The following year, Radama sent military expeditions along the northeast coast, establishing military posts at Maroantsetra, Tintingue and Mananjary. In 1824 further expeditions established posts at Vohemar, Diego Suarez, and Mahajanga. In 1825 military posts were established in the southeastern coastal towns of Farafangana and Fort Dauphin.[16] The Antalaotra were defeated in 1826 in a combined land and sea attack. Revolts by the Antanosy and Betsimisaraka prompted Radama to launch a military campaign to subjugate them. The Antesaka were conquered in Radama's final military campaign in 1827, and the northern Tanala became a vassalage. All together, Radama united two thirds of the island under Merina rule. The areas retaining independence included most of Bara country, Mahafaly and Antandroy in the south, a stretch of southern Tanala and the coastal area between Antesaka and Antanosy in the east, and northern Menabe and Ambongo in the west.[11]

Death and succession

Radama died prematurely on 27 July 1828, at his residence (the Tranovola).[17] Historical sources provide conflicting accounts regarding his cause of death. Many years of military campaigning certainly took their toll,[18] and Radama was prone to drinking heavily; shortly before his death he displayed symptoms of advanced alcoholism as his health rapidly declined. His death was officially declared to be the consequence of heavy intoxication.[19]

Radama was buried in a stone tomb on the grounds of the Rova of Antananarivo. In line with Malagasy architectural norms, his tomb was topped with a trano masina ("sacred house") symbolic of royalty. Like his father Andrianampoinimerina and other Merina sovereigns that would follow him, he was laid to rest in a silver coffin, and it is said the funerary goods buried with him were the most extensive and richest of any tomb in Madagascar. These included a deep red silk lamba mena, imported paintings of European royalty, thousands of coins, eighty articles of clothing, swords, jewels, gold vases, containers of silver and so forth. Alongside each interior wall of the trano masina were a mirror, bed, several chairs and a table upon which were placed two porcelain water vessels and one bottle each of water and rum that were replenished annually during the fandroana (festival of the royal bath). Most of these items were lost when a 1995 fire destroyed the Rova of Antananarivo where the tomb was located.[20]

Radama died without naming a clear successor,[18] but according to local custom, the rightful heir was Rakotobe, the eldest son of Radama's eldest sister. Radama died in the company of two trusted courtiers who were favorable to the succession of Rakotobe. However, they hesitated to report the news of Radama's death for several days, fearing possible reprisals against them for having been involved in denouncing one of the king's rivals, whose family had a stake in the succession after Radama.[21][22] During this time, another courtier, a high-ranking military officer named Andriamamba, discovered the truth and collaborated with other powerful officers - Andriamihaja, Rainijohary and Ravalontsalama - to support Ramavo, Radama's highest ranking wife, as successor.[23] She ultimately succeeded Radama as Queen Ranavalona I.[18]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Radama I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Madagascar. Written by Olivier Cirendini

- Campbell 2012, p. 719.

- Ade Ajayi 1998, p. 165.

- Campbell 2012, p. 627.

- Campbell 2012, p. 503.

- Callet 1908, pp. 345-355.

- Fage, Flint & Oliver 1986, p. 400.

- Callet 1908, p. 430.

- Fage, Flint & Oliver 1986, p. 402.

- Ade Ajayi 1998, p. 174.

- Fage, Flint & Oliver 1986, p. 405.

- Fage, Flint & Oliver 1986, p. 406.

- Middleton 1999, p. 68.

- Middleton 1999, p. 67.

- Fage, Flint & Oliver 1986, p. 5.

- Ade Ajayi 1998, p. 166.

- Montgomery 1840, pp. 283-286.

- Fage, Flint & Oliver 1986, p. 407.

- Ade Ajayi 1998, pp. 164–175.

- Frémigacci 1999, pp. 421-444.

- Freeman & Johns 1840, pp. 7-17.

- Oliver 1886, pp. 42-45.

- Rasoamiaramanana, Micheline (1989–1990). "Rainijohary, un homme politique meconnu (1793–1881)". Omaly Sy Anio (in French). 29–32: 287–305.

Bibliography

- Ade Ajayi, Jacob Festus (1998). General history of Africa: Africa in the nineteenth century until the 1880s. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 9780520067011.

- Callet, François (1908). Tantara ny andriana eto Madagasikara (histoire des rois) (in French). Antananarivo: Imprimerie Catholique.

- Campbell, Gwyn (2012). David Griffiths and the Missionary "History of Madagascar". Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-20980-0.

- Fage, J.D.; Flint, J.E.; Oliver, R.A. (1986). The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1790 to c. 1870. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20413-5.

- Freeman, Joseph John; Johns, David (1840). A narrative of the persecution of the Christians in Madagascar: with details of the escape of six Christian refugees now in England. Berlin: J. Snow.

- Frémigacci, Jean (1999). "Le Rova de Tananarive: Destruction d'un lieu saint ou constitution d'une référence identitaire?". In Chrétien, Jean-Pierre (ed.). Histoire d'Afrique (in French). Antananarivo: Karthala Editions. pp. 421–444. ISBN 9782865379040.

- Middleton, Karen (1999). Ancestors, Power, and History in Madagascar. The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 9004112898.

- Montgomery, James (1840). "Chapter LII: Funeral of King Radama". Voyages and travels around the world. London: London Missionary Society.

- Oliver, Samuel (1886). Madagascar: An Historical and Descriptive Account of the Island and its Former Dependencies. 1. New York: Macmillan and Co.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Radama I. |