Angakkuq

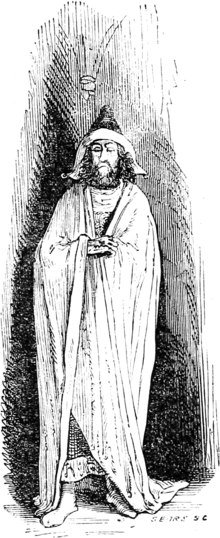

The Inuit angakkuq (plural: angakkuit, Inuktitut syllabics ᐊᖓᑦᑯᖅ or ᐊᖓᒃᑯᖅ[1][2][3]) Inuvialuktun: angatkuq;[4] Greenlandic: angakkoq,[5] pl. angákut[6]) is an intellectual and spiritual figure in Inuit culture who corresponds to a medicine man. Other cultures, including Alaska Natives, have traditionally had similar spiritual mediators, although the Alaska Native religion has many forms and variants.

Role in Inuit society

Both women, such as Uvavnuk, and men could become an angakkuq,[7] although it was rarer for women to do so. The process for becoming an angakkuq varied widely. The son of a current angakkuq might be trained by his father to become one as well.[8] A shaman might make a prophecy that a particular infant would become a prophet in adulthood.[9] Alternatively, a young man or woman who exhibited a predilection or power that made them stand out might be trained by an experienced mentor. There are also instances of angakkuit claiming to have been called to the role through dreams or visions.[8] Mistreated orphans or people who had survived hard times might also become angakkuit with the help of the spirits of their dead loved ones.[3]

Training to become an angakkuq consisted of acculturation to the rites and roles necessary for the position, as well as instruction in the special language of the angakkuit,[10] which consisted largely of an archaic vocabulary and oral tradition that was shared across much of the Arctic areas the Inuit occupied. During their training, the angakkuq would also gain a familiar or spirit guide who would be visible only to them.[8] This guide, called a tuurngaq in the Inuit religion, would at times give them extraordinary powers. Inuit stories tell of agakkuit who could run as fast as caribou, or who could fly, with the assistance of their tuurngaq. In some traditions, the angakkuq would be either stabbed or shot, receiving no wound because of the intervention of their tuurngaq, thus proving their power.[3]

Until spiritual guidance or assistance was needed, an angakkuq lived a normal life for an Inuit, participating in society as a normal person. But when sickness needed to be cured, or divination of the causes of various misfortunes was needed, the angakkuq would be called on.[8] The services of an angakkuit might also be required to interpret dreams.[3] If they were called to perform actions that helped the entire village, the work was usually done freely. But if they were called to help an individual or family, they would usually receive remuneration for their efforts.[8]

Amongst the Inuit, there are notions comparable to laws:

- tirigusuusiit, things to avoid

- maligait, things to follow

- piqujait, things to do

If these three are not obeyed, then the angakkuq may need to intervene with the offending party in order to avoid harmful consequence to the person or group.[11] Breaking these laws or taboos was seen as the cause of misfortune, such as bad weather, accidents, or unsuccessful hunts. In order to pinpoint the cause of such misfortune, the angakkuq would undertake a spirit-guided journey outside of their body. They would discover the cause of the misfortune on this journey. Once they returned from the journey, the angakkuq would question people involved in the situation, and, under the belief that they already knew who was responsible, the people being questioned would often confess. This confession alone could be declared the solution to the problem, or acts of penance such as cleaning the urine pots or swapping wives might be necessary.[8]

The angakkuit of the central Inuit participated in an annual ceremony to appease the mythological figure Sedna, the Sea Woman. The Inuit believed that Sedna became angry when her taboos were broken, and the only way to appease her was for an angakkuq to travel in spirit to the underworld where she lived, Adlivun, and smooth out her hair. According to myth, this was of great assistance to Sedna because she lacks fingers. The angakkuq would then beg or fight with Sedna to ensure that his people would not starve, and the Inuit believed that his pleading and apologies on behalf of his people would allow the animals to return and hunters to be successful. After returning from this spirit journey, communities in which the rite was practiced would have communal confessions, and then celebration.[8]

Auxiliary spirits and personal names

Angakkuit often had associations with entities that Canadian anthropologist and ethnographer Bernard Saladin d'Anglure referred to as "auxiliary spirits". These spirits could be the souls of the deceased or non-human entities, and each had an individual name, which could be used to invoke that spirit.[9] When a birth was particularly dangerous, or an infant could not be quieted down, it was believed that a dead family member was trying to live again through the infant, and that the infant should be named for that person. In cases where the family was not able to determine the name of the deceased person, perhaps because the infant's condition was too grave to provide enough time, the angakkuq could name the infant for one of their auxiliary spirits, providing the child with life-saving vigor.[12] Saladin d'Anglure reported that such children would be more likely to become shamans, connected by name to that auxiliary spirit.[13] Sometimes the name given would be that of a non-human spirit; the individual might then identify with that spirit later in life.[14]

Name and identity could be more fluid in adulthood, and at times of crisis a shaman might ritually rename a person; going forward, their old name would be considered an auxiliary spirit. This sometimes served as an initiation into shamanism for the renamed person. Saladin d'Anglure describes one such situation: a man called Nanuq ("polar bear") had been named for an older cousin. When the cousin died, the younger man was distraught and felt that he, too, had suffered a death. A shaman brought a new name for him from the dream world, which he adopted. Going forward, he was called Qimuksiraaq, and his old name and identity, Nanuq, was considered to be an auxiliary spirit associated with polar bears. Following this, Qimuksiraaq took on the identity of an angakkuq.[15]

Finally, an angakkuq might pass on their own personal name to their descendants, either before or after their death. In posthumous cases, the shaman might appear in a dream and direct the family personally, or the family might decide to honor the angakkuq of their own accord to maintain their link to the family.[16] A person who was named for a shaman might inherit some of their spiritual powers, but was not necessarily bound to become a shaman themselves.[17]

Further reading

- E. Haase, Der Schamanismus des Eskimos (1987)

- M. Jakobsen, Shamanism: Traditional and Contemporary Approaches to the Mastery of Spirits and Healing (1999)

- D. Merkur, Becoming Half Hidden: Shamanism and Initiation among the Inuit (1985)

References

- "Eastern Canadian Inuktitut-English Dictionary ᐊᖓᑦᑯᖅ". Glosbe. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- "Eastern Canadian Inuktitut-English Dictionary ᐊᖓᒃᑯᖅ". Glosbe. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- "Dreams and Angakkunngurniq : Becoming an Angakkuq". Francophone Association of Nunavut. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- "Inuinnaqtun to English" (PDF). Copian. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- Often previously transliterated angekok.

- Encyclopædia Britannica

- Freuchen, Dagmar (1960). Peter Freuchen's Adventures in the Arctic. New York: Messner. p. 136.

- Bastian, Dawn E.; Mitchell, Judy K. (2004). Handbook of Native American Mythology. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 47–49. ISBN 1-85109-533-0.

- Saladin D'Anglure, Bernard (2006). "The Construction of Shamanic Identity among the Inuit of Nunavut and Nunavik". In Christie, Gordon (ed.). Aboriginality and Governance: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Penticton Indian Reserve, British Columbia: Theytus Books. p. 142. ISBN 1894778243.

- Freuchen, Dagmar (1960). Peter Freuchen's Adventures in the Arctic. New York: Messner. p. 132.

- "Tirigusuusiit and Maligait". tradition-orale.ca. Archived from the original on 14 November 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- Saladin D'Anglure 2006, p. 143.

- Saladin D'Anglure 2006, p. 143–144.

- Saladin D'Anglure 2006, p. 144.

- Saladin D'Anglure 2006, p. 145–146.

- Saladin D'Anglure 2006, p. 146.

- Saladin D'Anglure 2006, p. 147–148.

External links

- Qaujimajatuqangit and social problems in modern Inuit society. An elders workshop on angakkuuniq- by Jarich Oosten and Frédéric Laugrand, 2002

- Shamanism - the powers of the angakkuq- SILA, 2005