Alaska Natives

Alaska Natives or Alaskan Natives are indigenous peoples of Alaska, United States and include: Iñupiat, Yupik, Aleut, Eyak, Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, and a number of Northern Athabaskan cultures. They are often defined by their language groups. Many Alaska Natives are enrolled in federally recognized Alaska Native tribal entities, who in turn belong to 13 Alaska Native Regional Corporations, who administer land and financial claims.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ≈106,660 (2006)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Russian (historically and spoken by some), Haida, Tsimshianic languages, Eskimo–Aleut languages (Inupiaq, Central Alaskan Yup'ik, Alutiiq, Aleut), Chinook Jargon, Na-Dené languages (Northern Athabaskan, Eyak, Tlingit), others | |

| Religion | |

| Shamanism (largely ex), Alaska Native religion, Christianity (Protestantism, Eastern Orthodoxy, American Orthodox Church and Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, Roman Catholicism), Bahá'í | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Native Americans, First Nations, Inuit |

.png.webp)

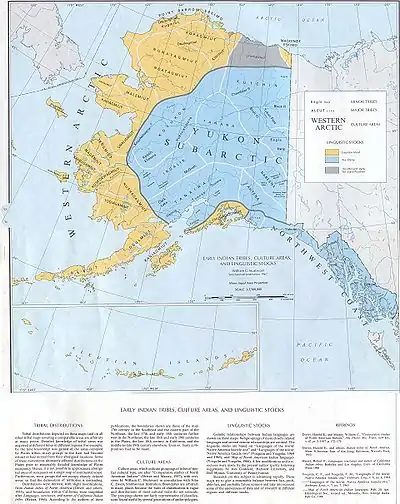

Ancestors of Alaska Natives migrated into the area thousands of years ago, in at least two different waves. Some are descendants of a third wave of migration in which people settled across the northern part of North America. They never migrated to southern areas. For this reason, genetic studies show they are not closely related to native peoples in South America.

Throughout the Arctic and the circumpolar north, the ancestors of Alaska Natives established varying indigenous, complex cultures that have succeeded each other over time. They developed sophisticated ways to deal with the challenging climate and environment, and cultures rooted in the place. Historic groups have been defined by their languages, which belong to several major language families. Today, Alaska Natives constitute over 15% of the population of Alaska.[2]

List of peoples

Below is a full list of the different Alaska Native peoples, which are largely defined by their historic languages (within each culture are different tribes):

- Ancient Beringian

- Alaskan Athabaskans

- Ahtna

- Deg Hit'an

- Dena'ina

- Gwich'in

- Hän

- Holikachuk

- Koyukon

- Lower Tanana

- Tanacross

- Upper Tanana

- Upper Kuskokwim (Kolchan)

- Eyak

- Tlingit

- Haida

- Tsimshian

- Eskimo

- Iñupiat, an Inuit group

- Yupik

- Siberian Yupik

- Yup'ik

- Cup'ik

- Nunivak Cup'ig

- Sugpiaq ~ Alutiiq

- Chugach Sugpiaq

- Koniag Alutiiq

- Aleut (Unangan)

Demographics

The Alaska Natives Commission estimated there were about 86,000 Alaska Natives living in Alaska in 1990, with another 17,000 who lived outside Alaska.[3] A 2013 study by the Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development documented over 120,000 Alaska Native people in Alaska.[4] While the majority of Alaska Natives live in small villages or remote regional hubs such as Nome, Dillingham, and Bethel, the percentage who live in urban areas has been increasing. In 2010, 44% lived in urban areas, compared to 38% in the 2000 census.[4] As of 2018, natives constitute 15.4% of the overall Alaskan population.[5]

History

The modern history of Alaskan natives begins with the arrival of Europeans. Unusual for North America, it was the Russians coming from Siberia in the eighteenth century, who were the first to make contact. British and American traders generally did not reach the area until the nineteenth century, and in some cases missionaries were not active until the twentieth century.

Russian colonial period

Arriving from Siberia by ship in the mid-eighteenth century, Russians began to trade with Alaska Natives. New settlements around trading posts were started by Russians, including Russian Orthodox missionaries. These were the first to translate Christian scripture into Native languages. In the 21st century, the numerous congregations of Russian Orthodox Christians in Alaska are generally composed mostly of Alaska Natives.

Rather than hunting the marine life, the Russians forced the Aleuts to do the work for them.[6] As word spread of the riches in furs to be had, competition among Russian companies increased and they forced the Aleuts into slavery.[6] Catherine the Great, who became Empress in 1763, proclaimed good will toward the Aleut and urged her subjects to treat them fairly. The growing competition between the trading companies, merging into fewer, larger and more powerful corporations, created conflicts that aggravated the relations with the indigenous populations. Over the years, the situation became catastrophic for the natives.

As the animal populations declined, the Aleuts, already too dependent on the new barter economy created by the Russian fur trade, were increasingly coerced into taking greater risks in the dangerous waters of the North Pacific to hunt for more otter. As the Shelikhov-Golikov Company and later Russian-American Company developed as a monopoly, it used skirmishes and systematic violence as a tool of colonial exploitation of the indigenous people. When the Aleut revolted and won some victories, the Russians retaliated, killing many and destroying their boats and hunting gear, leaving them no means of survival.

The most devastating effects were from disease: during the first two generations (1741/1759-1781/1799 AD) of Russian contact, 80 percent of the Aleut population died from Eurasian infectious diseases. These were then endemic among the Europeans, but the Aleut had no immunity against the new diseases.[7]

Impact of Russian colonization

Geopolitical reasons drove the Tsarist government to expand into Indigenous territory in present-day Alaska, spreading Russian Orthodoxy and consuming the natural resources of the territory along their way.[8] Their movement into these populated areas of Indigenous communities altered the demographic and natural landscape. Historians have suggested that the Russian-American Company exploited Indigenous peoples as a source of inexpensive labour.[8] The fur trade led the Russian American Company to not only use Indigenous populations for labour, but to also use them as hostages to acquire iasak.[8] Iasak, a form of taxation used by the Russians, was a tribute in the form of otter pelts.[8] It was a taxation method the Russians had previously found useful in their early encounter with Indigenous communities of Siberia during the Siberian fur trade.[8] Beaver pelts were also customary to be given to fur traders upon first contact with various communities.[9]

The Russian American Company used military force on Indigenous families as they were taken hostage and held until the male community members brought forth furs.[8] Otter furs on Kodiak Island and Aleutian Islands enticed the Russians to start these taxations.[8] Robbery and maltreatment in the form of corporal punishment and the withholding of food was also present upon the arrival of fur traders.[10] Catherine the Great dissolved the giving of tribute in 1799, and instead instituted a mandatory conscription of Indigenous men between the ages of 18 to 50 to become seal hunters strictly for the Russian American Company.[8] Mandatory service of Indigenous men gave the Russian American Company grounds for competition with American and British fur traders.[8] The conscription of mandatory labour separated men from their families and villages, thus altering and breaking down communities.[11] With able-bodied men away on the hunt, villages were left with little protection as only women, children, and the elderly remained behind.[11] In addition to changes that came with conscription, the spread of disease also altered populations of Indigenous communities.[12] Although records kept in the period were scarce, it has been said that 80% of the pre-contact population of the Aleut people were gone by 1800.[12]

Relationships between Indigenous women and fur traders increased as Indigenous men were away from villages. This resulted in marriages and children that would come to be known as Creole peoples, children who were Indigenous and Russian.[11] To reduce hostilities with Aleutian communities, it became policy for fur traders to enter into marriage with Indigenous women which also helped grow a strong Creole population in the territory controlled by the Russian American Company.[11]

The growth of the Russian Orthodox Church was another important tactic in the colonization and conversion of Indigenous populations.[13] Ioann Veniaminov, who later became Saint Innocent of Alaska, was an important missionary who carried out the Orthodox Church's agenda to Christianize Indigenous populations.[13] The church brought up Creole children following Russian Orthodox Christianity, while the Russian American Company provided an education to them.[13] Creole people were considered to have high levels of loyalty towards the Russian crown and Russian American Company.[13] After completing their education, children were often sent to Russia, where they would study skills such as mapmaking, theology, and military intelligence.[13]

American colonialism

In 1867, the United States purchased Alaska from Russia and did not consider the wishes of Alaska Natives or even see them as citizens.[14] The land that belonged to Alaska Natives was now seen as "open land" which could be claimed by white settlers without redress to the Alaska Natives living there.[14] There were no schools for Alaska Natives except where missionaries created educational institutions.[15] Most white settlers considered Alaska Natives to be inferior to them.[16] Alaska Natives began to live under racial segregation and Jim Crow laws.[17]

In 1912, the Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANB) was formed to help fight for citizenship rights.[18] The Alaska Native Sisterhood (ANS) was created in 1915.[19] Also in 1915, the Alaska Territorial legislature passed a law allowing Alaskan Natives the right to vote if they gave up their cultural customs and traditions.[20] The Indian Citizenship Act, passed in 1924, gave all Native Americans United States citizenship.[20]

ANB began to hold a great deal of political power in the 1920s.[21] They protested the segregation of Alaska Natives in public areas and also staged boycotts.[22] Alberta Schenck (Inupiaq) staged a well-publicized protest against segregation in a movie theater in 1944.[23] With the help of Elizabeth Peratrovich (Tlingit), the Alaska Equal Rights Act of 1945 was passed, ending segregation in Alaska.[24]

A tragic event that took place in 1942 was the forced evacuation of around nine hundred Aleuts from the Aleutian Islands.[25] The idea was to remove the Aleuts from a potential combat zone during World War II for their own protection, though white people living in the same area were not forced to leave.[25] The removal was handled so poorly that many died after they were evacuated with elderly and children being at the greatest risk.[26] Those who lived returned to the islands to find their homes and possessions destroyed or looted.[25]

ANCSA and since (1971 to present)

In 1971, with the support of Alaska Native leaders such as Emil Notti, Willie Hensley, and Byron Mallot, the U.S. Congress passed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA), which settled land and financial claims for lands and resources which the Alaska Natives had lost to European-Americans. It provided for the establishment of thirteen Alaska Native Regional Corporations to administer those claims. Similar to the separately defined status of the Canadian Inuit and First Nations in Canada, which are recognized as distinct peoples, in the United States, Alaska Natives are in some respects treated separately by the government from other Native Americans in the United States. This is in part related to their interactions with the U.S. government which occurred in a different historic period than its interactions during the period of westward expansion during the 19th-century.

Europeans and Americans did not have sustained encounters with the Alaska Natives until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when many were attracted to the region in gold rushes. The Alaska Natives were not allotted individual title in severalty to land under the Dawes Act of 1887 but were instead treated under the Alaska Native Allotment Act of 1906.[27]

It was repealed in 1971, following ANSCA, at which time reservations were ended. Another characteristic difference is that Alaska Native tribal governments do not have the power to collect taxes for business transacted on tribal land, per the United States Supreme Court decision in Alaska v. Native Village of Venetie Tribal Government (1998). Except for the Tsimshian, Alaska Natives no longer hold reservations but do control some lands. Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, Alaska Natives are reserved the right to harvest whales and other marine mammals.

Subsistence

Gathering of subsistence food continues to be an important economic and cultural activity for many Alaska Natives.[28] In Utqiagvik, Alaska in 2005, more than 91 percent of the Iñupiat households which were interviewed still participated in the local subsistence economy, compared with the approximately 33 percent of non-Iñupiat households who used wild resources obtained from hunting, fishing, or gathering.[29]

But, unlike many tribes in the contiguous United States, Alaska Natives do not have treaties with the United States that protect their subsistence rights,[28] except for the right to harvest whales and other marine mammals. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act explicitly extinguished aboriginal hunting and fishing rights in the state of Alaska.[30]

See also

- Ancient Beringian

- List of Alaska Native Tribal Entities, the list of Native Villages and other "tribal entities" recognized by the US Bureau of Indian Affairs.

- Prehistory of Alaska

- First Alaskans Institute

- Indigenous Amerindian genetics

- Circumpolar peoples

- Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast

- Indigenous peoples of the Subarctic

- Indigenous peoples of Siberia

- Alaska Native Storytelling

- Alaska Equal Rights Act of 1945

- Women's suffrage in Alaska

References

- china Department ofWorkforce Development. (2006). "Table 1.8 Alaska Native American Population Alone By Age And Male/Female, July 1, 2006." Alaska Department of Labor & Workforce Development, Research & Analysis. Retrieved on 2007-05-23.

- "U.S. Census Bureau Quick Facts". 2017.

- "Alaska Natives Commission".

- "The Alaska Native Population Is on an Upward Trend". KOLG Public Radio for Bristol Bay.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Alaska". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- Taylor, Alan (2001) American Colonies: The Settling of North America Penguin Books, New York p.452

- "Aleut History", The Aleut Corporation Archived November 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Lightfoot, Ken G (2003). "Russian Colonization: The Implications of Mercantile Colonial Practices in the North Pacific". Historical Archaeology. 37 (4): 14–28. doi:10.1007/BF03376620. JSTOR 25617092.

- Five Journal Reports From 1789-90 Concerning Treatments of Aleuts

- Journal of Navigator Potap Zaikov, on Ship, "Alexander Nevski"

- Reedy-Maschen, Katherine (Fall 2018). "Where Did All the Aleut Men Go? Aleut Men Attrition and Related Patterns in Aleutian Historical Demography and Social Organization". Human Biology. 82 (5/6): 583–611. doi:10.3378/027.082.0506. JSTOR 41466705. PMID 21417885.

- Veltre, Douglas, W (Fall 2018). "Russian Exploitation of Aleuts and Fur Seals: The Archaeology of Eighteenth Century and Early Nineteenth Century Settlements in the Pribilof Island, Alaska". Historial Archaeology. 36 (3): 8–17. doi:10.1007/BF03374356. JSTOR 25617008.

- Dehass, Media Csoba (Fall 2018). "What is in a Name? The Predicament of Ethnonyms in the Sugpi-aq- Aluitq Region of Alaska". Arctic Archaeology. 49 (1): 3–17. JSTOR 24475834.

- Tucker, Landreth & Lynch 2017, p. 329.

- Tucker, Landreth & Lynch 2017, p. 330-331.

- Cole 1992, p. 431.

- Cole 1992, p. 428.

- Cole 1992, p. 432.

- Sostaric, Katarina (2015-10-12). "Alaska Native Sisterhood celebrates 100th anniversary in Wrangell". KTOO. Retrieved 2020-11-08.

- "First Territorial Legislature of Alaska". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2020-11-09.

- Cole 1992, p. 432-433.

- Cole 1992, p. 434-435.

- Cole 1992, p. 440-441.

- Cole 1992, p. 449.

- Cole 1992, p. 438.

- Cole 1992, p. 438-439.

- Elizabeth Barrett Ristroph, "Alaska Tribes' Melting Subsistence Rights," 1 Arizona Journal of Environmental Law & Policy 1, 2010, Available at "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2011-04-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- URS CORP., BARROW VILLAGE PROFILE 4.3-6 (2005), available at http://www.north-slope.org/information/comp_plan/BarrowVillageProfile06.pdf%5B%5D

- 43 U.S.C. § 1603(b) (2006)

Sources

- Cole, Terrence M. (November 1992). "Jim Crow in Alaska: The Passage of the Alaska Equal Rights Act". Western Historical Quarterly. 23 (4): 429–449. doi:10.2307/970301 – via JSTOR.

- Tucker, James Thomas; Landreth, Natalie A.; Lynch, Erin Dougherty (2017). "'Why Should I Go Vote Without Understanding What I Am Going to Vote For?' The Impact of First Generation Voting Barriers on Alaska Natives". Michigan Journal of Race and Law. 22: 327–382.

Further reading

- Chythlook-Sifsof, Callan J. "Native Alaska, Under Threat." (Op-Ed) The New York Times. June 27, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alaska Natives. |

.svg.png.webp)