Anti-French sentiment in the United States

Anti-French sentiment in the United States has consisted of unfavorable estimations of the French government, culture, language or people of France (and to some degree Canada) from people in the United States of America.

18th century

The victory of the American colonists against the British was heavily dependent on the financial and military support of France. Despite the positive view of Jeffersonian Americans during the French Revolution, it awakened or created anti-French feelings among many Federalists. An ideological split was already emerging between pro-French and anti-French sentiment, with John Adams, Alexander Hamilton and their fellow Federalists taking a skeptical view of France, even as Thomas Jefferson and other Democratic-Republicans urged closer ties. As for the Revolution, many or most Federalists denounced it as far too radical and violent. Those on the Democratic-Republican side remained broadly supportive. Pierre Bourdieu and Stanley Hoffmann[1] have suggested that one of the roots of anti-French sentiments in the United States and anti-American sentiments in France is the claim of both countries that their social and political systems are "models" that universally apply. France's secularism was often something of an issue for the Americans. There are some similarities there to the Federalists' reaction to perceived French anti-clericalism.

In the 1790s, the French, under a new post-revolutionary government, accused the United States of collaborating with the British and proceeded to impound Britain-bound US merchant ships. Attempts at diplomacy led to the 1797 XYZ Affair and the Quasi-War fought entirely at sea between the United States and France from 1798 to 1801, heightening tensions between the two countries and leading to an increase in anti-French feelings in America.

19th and early 20th centuries

Relations somewhat improved after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. American cultured classes embraced French styles and luxuries after the Civil War: Americans trained as architects in the École des Beaux-Arts, French haute cuisine reigned at elite American tables, and upper-class women in the US followed Parisian clothing fashions. Following World War I, a generation of rich American expatriates and bohemians settled in Paris. That, however, did not help with the populist image of a liberal elite of American francophiles.

In the Southern United States, some Americans were anti-French for racist reasons. For example, John Trotwood Moore, a Southern novelist and local historian who served as the State Librarian and Archivist of Tennessee from 1919 to 1929, lambasted the French for "intermarrying with the Indians and treating them as equals" during the French colonization of the Americas.[2]

Allegation of missing French-American lobby

French historian Justin Vaïsse has proposed that an important cause of public hostility in the US is the small number of Americans of direct or recent French descent.[3][4] Most Americans of French descent are descended from 17th- and 18th-century colonists who settled in Quebec, Acadia, or Louisiana before migrating to the United States or being incorporated into American territories. French Americans of colonial era Huguenot descent, French Protestant emigrants, have often ceased identification with France.

World War II

The rout of French forces during the German invasion of France in 1940 came as a profound shock to Americans. As details of the defeat, specifically of the general surrender of the French Army against Nazi German forces in the Armistice of 22 June 1940.

When the United States entered the war, although France was ostensibly an ally, many factors contributed to significant anti-French sentiment. First, in Operation Torch, as the United States sacrificed thousands of soldiers' lives to liberate the French people, neither French resistance forces nor the opposing French Vichy authorities were easy to handle. The Allies succeeded in slipping French General Henri Giraud out of Vichy France and offered him the command of Free French forces in North Africa. Giraud, however, insisted on being nominated commander-in-chief of all the invading forces. Because this position was reserved for General Dwight Eisenhower, Giraud remained a spectator instead. At battles like Normandy and the Battle of the Bulge, tens of thousands of Americans lost their lives liberating France .

Within months of French liberation from the Germans, tensions rapidly rose between the locals and US military personnel stationed there. 112 Gripes about the French was a 1945 handbook issued by the United States military to defuse some of this hostility.

1945 to 2001

France's troubled history in Indochina and in the Algerian War of 1954-1962 led to some US criticism of France's ongoing colonial aspirations.

Relations worsened even more when French President Charles de Gaulle emphasized France's role as an independent power, in part by removing France from the joint military structure of NATO in 1966 and by vetoing Britain's entry into the EEC in 1961. De Gaulle's support for Quebec independence, as exemplified by his Vive le Québec libre speech in 1967, annoyed the Canadian, British and American governments.[5]

In 1966, as part of the military withdrawal from NATO, de Gaulle ordered all American soldiers to leave French soil.[6]

The Middle East

The term Eurafrique refers to the (important) idea of strategic partnership between Africa and Europe, and the conspiracy theory Eurabia refers to a putative French/Arab cabal to Islamize Europe. The Suez Crisis of 1956 marked a watershed for Israeli-French relations.[7][8] Israel, France, and the United Kingdom allied for control of the Suez Canal but then were forced to withdraw by the United States and the Soviet Union.[7][9] While France had previously been the main supporter of Israel, the United States took over its current role as ally of Israel with the Six-Day War in 1967.[10] This diplomatic development impaired French-US relations, as France was increasingly seen as an outdated and aggressive neocolonial power.

Osirak was a light-water reactor program in Iraq, derived primarily from French technology. In 1981 an attack by the Israeli Air Force destroyed the Osirak installation. The participation of the French government in the program worsened US-French relations for years to come.

France allied with the United States during the First Iraq War (1990-1991) and French forces in Afghanistan have played a role in the War in Afghanistan since 2001.

21st century

However, anti-French sentiment returned to the fore in the wake of France's refusal to support US proposals in the UN Security Council for military action to invade Iraq. While other nations also opposed the US proposals (notably Russia; China; and traditional US allies, such as Germany, Canada, and Belgium), France received particularly ferocious criticism.[11]

In 1990s popular culture, the derogatory phrase "cheese-eating surrender monkeys" began as a joke on The Simpsons in 1995, used by Groundskeeper Willie's character in a satirical manner. National Review contributor Jonah Goldberg claimed credit for making the term known, with its implicit characterization of the French as cowards.[12] In early 2003, George Will from The Washington Post described retreat as "an exercise for which France has often refined its savoir-faire since 1870."[13] Anti-French displays also came in the form of bumper stickers, and t-shirts calling for the United States to invade: "Iraq first, France next!"[14] and "First Iraq, then Chirac!"[15]

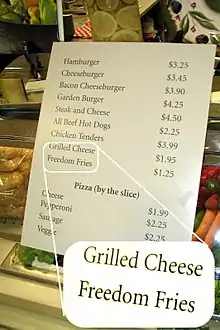

Freedom fries is a political euphemism for French fries. The term came to prominence in 2003 when the then Republican Chairman of the Committee on House Administration, Bob Ney, renamed the menu item in three Congressional cafeterias in response to France's opposition to the proposed invasion of Iraq.

References

- Pierre Bourdieu, « Deux impérialismes de l'universel », in Christine Fauré and Tom Bishop, L'Amérique des Français, Paris, F. Bourin, 1992 ; Stanley Hoffmann, « Deux universalismes en conflit », The Tocqueville Review, Vol.21 (1), 2000.

- Bailey, Fred Arthur (Spring 1999). "John Trotwood Moore and the Patrician Cult of the New South". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 58 (1): 22. JSTOR 42627447.

- Politique Internationale – La Revue

- Pierre Verdaguer, "A Turn-of-the-Century Honeymoon? The Washington Post's Coverage of France", French Politics, Culture & Society, vol. 21, no. 2, summer 2003.

- "Vivre_le_Quebec_Libre!".html "Charles de Gaulle and "Vivre le Quebec Libre!"". Encyclopedia of French Cultural Heritage in North America. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- Ogden, Christopher (1995-09-18). "Bombs Away!". Time. 146 (12). pp. 166–189. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- David Newman (2010-03-28). "Repairing Israel-UK Relations". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2012-01-12.

- Ian Black (2010-02-18). "Dubai killing deals another blow to faltering UK-Israel relations". Guardian. London. Retrieved 2012-01-12.

- "Israel threatens British boycott". The Times. London.

- When Israel and France Broke Up, NYT GARY J. BASS, March 31, 2010

- See Condoleezza Rice: "Punish France, ignore Germany, and forgive Russia."

- "Inscrutable Racism", National Review, April 6, 2001

- "Wimps, weasels and monkeys — the US media view of 'perfidious France'", Guardian Unlimited, February 11, 2003

- First Iraq, then France T-Shirts Archived April 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Johnson, Bridget (11 February 2005). "All Things Fair". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved 17 May 2018.