Quasi-War

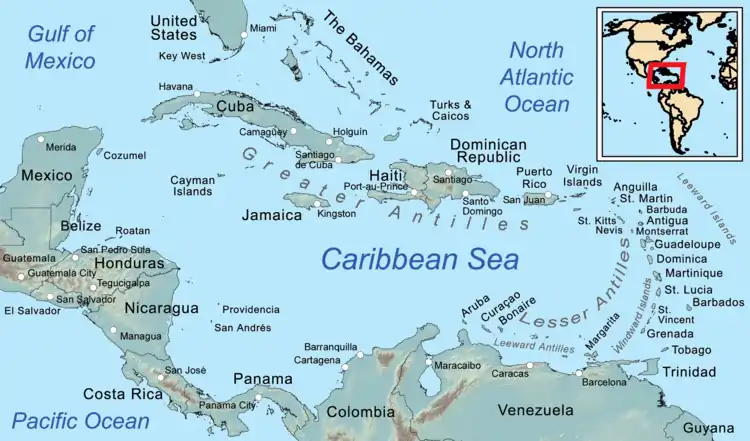

The Quasi-War (French: Quasi-guerre) was an undeclared war fought from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and France. Most of the fighting took place in the Caribbean and off the Atlantic coastline of the United States.

| Quasi-War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Second Coalition | |||||||

Left: USS Constellation vs L'Insurgente; right: U.S. Marines from USS Constitution boarding and capturing French privateer Sandwich | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

The war originated in disputes over the application of the 1778 treaties of Alliance and Commerce between the two countries. France, then engaged in the 1792–1797 War of the First Coalition, which included Great Britain, viewed the 1794 Jay Treaty between the United States and Britain as incompatible with those treaties, and retaliated by seizing American ships trading with Britain.

The United States responded by suspending repayment of French loans from the American Revolutionary War. When diplomatic negotiations, culminating in the XYZ Affair, failed to resolve the issue, French privateers began attacking merchant ships in American waters. On July 7, 1798, Congress authorized the use of military force against France, and re-established the United States Navy. United States Marines were also re-established to defend and board warships, as well as land troops if needed.

The United States informally cooperated with Britain, chiefly in allowing merchant ships to join each other's convoys. Likewise, France cooperated with Spain on a minor scale.

President John Adams continued diplomatic efforts to resolve underlying issues; this coincided with Napoleon taking power in France, who, for various reasons, was keen to agree to terms. This led to the Convention of 1800, which ended the war.

Background

Under the Treaty of Alliance (1778), the United States agreed to protect French colonies in the Caribbean in return for their support in the American Revolutionary War. As the treaty had no termination date, this obligation technically included defending them from British and Dutch attacks during the 1792 to 1797 War of the First Coalition. Despite popular enthusiasm for the French Revolution, there was little support for this in Congress; neutrality allowed Northern shipowners to earn huge profits evading the British blockade, and Southern plantation-owners feared the example set by France's abolition of slavery in 1794.[2]

Arguing the 1793 execution of Louis XVI void existing agreements, the France Neutrality Act of 1794 unilaterally cancelled the military obligations of the 1778 treaty. France accepted on the basis of 'benevolent neutrality', which meant allowing French privateers access to US ports, and the right to sell captured British ships in American prize courts, but not vice versa. It was soon apparent the US interpreted 'neutrality' as the right to trade with and provide the same privileges to both.[3]

This conflict became apparent when the US agreed to the 1794 Jay Treaty with Britain, which contradicted the 1778 Commercial Treaty with France. It resolved outstanding issues from the American Revolution, and expanded trade between the two countries; between 1794 and 1801, American exports nearly tripled in value, from US$33 million to $94 million. The treaty was opposed by the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans, who were generally pro-French and anti-British.[4]

When France retaliated by seizing American ships trading with the British, an effective response was hampered by the almost complete lack of a United States Navy. Driven by Jeffersonian opposition to Federal institutions, its last warship had been sold in 1785, leaving only a small flotilla belonging to the United States Revenue Cutter Service and a few neglected coastal forts. This allowed French privateers to roam virtually unchecked; from October 1796 to June 1797, they captured 316 ships, 6% of the entire American merchant fleet, causing losses of $12 to $15 million.[5]

Congress responded by suspending repayment of French loans made during the Revolutionary War; efforts to resolve this through diplomacy ended in the 1797 dispute known as the XYZ Affair.[6] However, it created support for establishing a limited naval force, and on June 18, President John Adams appointed Benjamin Stoddert the first Secretary of the Navy.[7] On July 7, 1798, Congress approved the use of force against French warships in American waters.[8]

Forces and strategy

Since ships of the line were extremely expensive and required highly specialised construction facilities, Congress compromised by ordering six large frigates in 1794. Three were nearly complete by 1798, and on July 16, 1798, they approved funding for the USS Congress, USS Chesapeake, and USS President, plus the frigates USS General Greene and USS Adams. The provision of naval stores and equipment by the British allowed these to be built relatively quickly, and all saw action during the war.[9]

The US Navy was further reinforced by so-called 'subscription ships', privately funded vessels provided by individual cities. These included five frigates, among them the USS Philadelphia, commanded by Stephen Decatur, and four sloops, which were converted merchantmen. These privately funded vessels were noted for their speed, and very successful; the USS Boston captured over 80 enemy vessels, including the French corvette Berceau.[10]

With most of the French fleet confined to home ports by the Royal Navy, Secretary Stoddert was able to concentrate his forces against the limited number of frigates and smaller vessels that evaded the blockade and reached the Caribbean. The other need was for convoy protection, and while there was no formal agreement with the British, there was considerable co-operation at a local level. The two navies shared a signal system, and allowed their merchantmen to join each other's convoys, mostly provided by the British, since they had four to five times more escorts available.[11]

However, the biggest threat came from small privateers, carrying between one and twenty guns and of very shallow draft. Operating from French and Spanish bases in the Caribbean, particularly Guadeloupe, they made opportunistic attacks on passing ships, before escaping back into port. To combat this, the US used similar sized vessels from the United States Revenue Cutter Service, as well as commissioning their own privateers. The first American ship to see action was the USS Ganges, a converted East Indiaman with 26 guns; most were far smaller.[12]

Significant naval actions

From the perspective of the US Navy, the Quasi-War consisted of a series of ship to ship actions in US coastal waters and the Caribbean; one of the first was the Capture of La Croyable on 7 July 1798, by Delaware outside Egg Harbor, New Jersey.[13] On 20 November, a pair of French frigates, Insurgente and Volontaire, captured the schooner USS Retaliation, commanded by Lieutenant William Bainbridge; Retaliation would be recaptured on 28 June 1799.

On 9 February 1799, the frigate Constellation captured the French Navy's frigate L'Insurgente and severely damaged the frigate La Vengeance, largely due to Captain Thomas Truxtun's focus on crew training. By 1 July, under the command of Stephen Decatur, USS United States had been refitted and repaired and embarked on its mission to patrol the South Atlantic coast and West Indies in search of French ships which were preying on American merchant vessels.[14]

On 1 January 1800, a convoy of American merchant ships and their escort, United States naval schooner USS Experiment, engaged a squadron of armed barges manned by French-allied Haitians known as picaroons off the coast of present-day Haiti. On 1 February, the American frigate USS Constellation unsuccessfully tried to capture the French frigate La Vengeance off the coast of Saint Kitts. In early May, Captain Silas Talbot organized a naval expedition to Puerto Plata on the island of Hispaniola in order to harass French shipping, capturing the Spanish coastal fort at Puerto Plata and a French corvette. Following the French invasion of Curaçao in July, the American sloops USS Patapsco and USS Merrimack began a blockade of the island in September that led to a French withdrawal. On 12 October, the frigate Boston captured the corvette Le Berceau. On 25 October, the USS Enterprise defeated the French brig Flambeau near the island of Dominica in the Caribbean Sea. Enterprise also captured eight privateers and freed eleven U.S. merchant ships from captivity, while Experiment captured the French privateers Deux Amis and Diane and liberated numerous American merchant ships.

American naval losses may have been light, but the French had successfully seized many American merchant ships by the war's end in 1800 – more than 2,000, according to one source.[16][17]

Role of the American Revenue-Marine

Revenue cutters in the service of the American Revenue-Marine also took part in the conflict. The cutter USRC Pickering, commanded by Edward Preble, made two cruises to the West Indies and captured ten prizes. Preble turned command of Pickering over to Benjamin Hillar, who captured the much larger and more heavily armed French privateer l'Egypte Conquise after a nine-hour battle. In September 1800, Hillar, Pickering, and her entire crew were lost at sea in a storm. Preble next commanded the frigate USS Essex, which he sailed around Cape Horn into the Pacific to protect U.S. merchantmen in the East Indies. He recaptured several U.S. ships that had been seized by French privateers.[18][19][20]

Involvement of the Royal Navy

For various reasons, the support provided by the Royal Navy was minimised at the time, and since; its most significant contribution was convoying merchant shipping, freeing the US Navy to attack French privateers. As a result, the first significant study of the war by US naval historian Gardner W Allen in 1909 focused exclusively on ship to ship actions, and this is how the war is remembered.[21]

In his work Stoddert’s War: Naval Operations During the Quasi-War with France, 1798-1801, historian Michael Palmer writes;

American naval operations of the Quasi-War cannot be understood in isolation. When the ships of the USN made landfall in the Caribbean, they entered a European theater where the war had been underway since 1793. The Royal Navy deployed four to five times more men-of-war in the West Indies than the Americans. British ships chased and fought the same French cruisers and privateers. Both navies escorted each other’s merchantmen. American warships operated from British bases. And most importantly, British policies and shifts in deployment had dramatic effects on American operations.[22]

Conclusion of hostilities

By late 1800, the United States Navy and the Royal Navy, combined with a more conciliatory diplomatic stance by the government of First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte, had reduced the activity of the French privateers and warships. The Convention of 1800, signed on 30 September, ended the Quasi-War. It affirmed the rights of Americans as neutrals upon the sea and abrogated the alliance with France of 1778. However, it failed to provide compensation for the $20 million "French Spoliation Claims" of the United States. The agreement between the two nations implicitly ensured that the United States would remain neutral toward France in the wars of Napoleon and ended the "entangling" French alliance.[23] This alliance had been viable only between 1778 and 1783.[24]

See also

References

- Clodfelter 2002, pp. 136-137.

- Young 2011, pp. 436-466.

- Hyneman 1930, pp. 279–283.

- Combs 1992, pp. 23-24.

- Sechrest 2007, p. 103.

- Coleman 2008, p. 189.

- Williams 2009, p. 25.

- Eclov 2013, p. 67.

- Eclov 2013, p. 69.

- Sechrest 2007, p. 119.

- Eclov 2013, pp. 8-10.

- Eclov 2013, pp. 71-72.

- Mooney 1983, p. 84.

- Mackenzie 1846, p. 40.

- Lieutenant Colonel Gregory E. Fehlings, "America’s First Limited War", Naval War College Review, Volume 53, Number 3, Summer 2000

- Hickey, 2008, pp.67–77

- The United States Coast Guard The Coast Guard at War

- "USRCS Lost at Sea". Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- Love 1992, p. 68

- Allen 1909.

- Palmer 1987, p. x.

- Lyon 1940, pp. 305–333.

- DeConde 1966, pp. 162–184.

Bibliography

- Allen, Gardner Weld (1909). Our Naval War With France. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1202325.

- Clodfelter, Micheal (2002). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures 1500-1999. McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0786412044.

- Coleman, Aaron (2008). ""A Second Bounaparty?" A Reexamination of Alexander Hamilton during the Franco-American Crisis, 1796-1801". Journal of the Early Republic. 28 (2). JSTOR 30043587.

- Combs, Jerald A (1992). The Jay Treaty: Political Battleground of the Founding Fathers. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520015739.

- DeConde, Alexander (1966). The Quasi-War: The Politics and Diplomacy of the Undeclared War with France, 1797–1801. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Eclov, Jon Paul (2013). Informal Alliance: Royal Navy And U.S. Navy Co-Operation Against Republican France During The Quasi-War And Wars Of The French Revolution (PhD). University of North Dakota.

- Harris, Thomas (1837). The life and services of Commodore William Bainbridge, United States navy.

Carey Lea & Blanchard, Philadelphia. p. 254. ISBN 0945726589. - Hickey, Donald R. (2008). The Quasi-War: America's First Limited War, 1798–1801 (PDF). The Northern Mariner/le marin du nord, XVIII Nos. 3–4, July–October 2008.

- Jennings, John (1966). Tattered Ensign The Story of America's Most Famous Fighting Frigate, U.S.S. Constitution. Thomas Y. Crowell. OCLC 1291484.

- Knox, Dudley W., ed. (1939). Naval Documents related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers, Volume I. Washington: United States Government Printing Office. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- Kohn, Richard H. (1975). Eagle and Sword: The Federalists and the Creation of the Military Establishment in America, 1783–1802.

- Lyon, E Wilson (1940). "The Franco-American Convention of 1800". The Journal of Modern History. XII. JSTOR 1874761.

- Mackenzie, Alexander Slidell (1846). Life of Stephen Decatur: A Commodore in the Navy of the United States. C. C. Little and J. Brown.

- Mooney, James L., ed. (1983). Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. 6. Defense Dept., Navy, Naval History Division. ISBN 978-0-16-002030-8.

- Palmer, Samuel Putnam (1989). Stoddert's War: Naval Operations During the Quasi War with France, 1798-1801. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0872494993.

- Sechrest, Larry (2007). "Privately Funded and Built U.S. Warships in the Quasi-War of 1797–1801". The Independent Review. XII (1).

- Waldo, Samuel Putnam (1821). The Life and Character of Stephen Decatur. P. B. Goodsell, Hartford, Conn.

- Williams, Greg H. (2009). The French Assault on American Shipping, 1793–1813: A History and Comprehensive Record of Merchant Marine Losses. McFarland Publishers. ISBN 9780786454075.

- Young, Christopher J (2011). "Connecting the President and the People: Washington's Neutrality, Genet's Challenge, and Hamilton's Fight for Public Support". Journal of the Early Republic. 31 (3). JSTOR 41261631.

Further reading

- Bowman, Albert Hall. The struggle for neutrality: Franco-American diplomacy during the Federalist era (1974), online free

- Daughan, George C. (2008). If By Sea: The Forging of the American Navy – From the Revolution to the War of 1812. Philadelphia: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01607-5.

- Leiner, Frederick C. (1999). Millions for Defense: The Subscription Warships of 1798. Annapolis: US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-508-8.

- Love, Robert (1992). History of the U.S. Navy Volume One 1775–1941. Harrisburg PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-1862-2.

- Nash, Howard Pervear. The forgotten wars: the role of the US Navy in the quasi war with France and the Barbary Wars 1798–1805 (AS Barnes, 1968)

- Toll, Ian W. (2006). Six Frigates: The Epic History of the Founding of The U.S. Navy. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-05847-5.

- Unger, Harlow (2005). The French War Against America: How a Trusted Ally Betrayed Washington and the Founding Fathers. Hoboken NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-65113-0.

- Williams, Greg H. (2009). The French Assault on American Shipping, 1793–1813: A History and Comprehensive Record of Merchant Marine Losses. McFarland. ISBN 9780786454075.

External links

- "Selected Bibliography of The Quasi-War with France" compiled by the United States Army Center of Military History

- U.S. Department of State "The XYZ Affair and the Quasi-War with France, 1798–1800"

- "U.S. treaties and federal legal documents re 'Quasi-War with France 1791–1800'", compiled by the Lillian Goldman Law Library of Yale Law School