Archaellum

An archaellum (plural: archaella, formerly archaeal flagellum) is a unique whip-like structure on the cell surface of many archaea. The name was proposed in 2012 following studies that showed it to be evolutionarily and structurally different from the bacterial and eukaryotic flagella. The archaellum is functionally the same – it can be rotated and is used to swim in liquid environments. The archaellum was found to be structurally similar to the type IV pilus.[1][2]

History

In 1977, archaea were first classified as a separate group of prokaryotes in the three-domain system of Carl Woese and George E. Fox, based on the differences in the sequence of ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) genes.[3][4] This domain possesses numerous fundamental traits distinct from both the bacterial and the eukaryotic domains. Many archaea possess a rotating motility structure that at first seemed to resemble the bacterial and eukaryotic flagella. The flagellum (Latin for whip) is a lash-like appendage that protrudes from the cell. In the last two decades, it was discovered that the archaeal flagella, although functionally similar to bacterial and eukaryotic flagella, structurally resemble bacterial type IV pili.[5][6][7] Bacterial type IV pili are surface structures that can be extended and retracted to give a twitching motility and are used to adhere to or move on solid surfaces; their "tail" proteins are called pilins.[8][9] To underline these differences, Ken Jarrell and Sonja-Verena Albers proposed to change the name of the archaeal flagellum to archaellum.[10]

Structure

Components

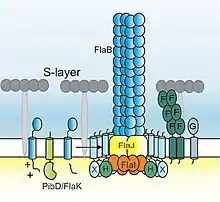

Most proteins that make up the archaellum are encoded within one genetic locus. This genetic locus contains 7-13 genes which encode proteins involved in either assembly or function of the archaellum.[7] The genetic locus contains genes encoding archaellins (flaA and flaB)[lower-alpha 1] - the structural components of the filament - and motor components (flaI, flaJ, flaH). The locus furthermore encodes other accessory proteins (flaG, flaF, flaC, flaD, flaE, and flaX). FlaX is only found in Crenarchaeota and FlaCDE (which can exist as individual proteins or as fusion proteins) in Euryarchaeotes. FlaX and FlaCDE are thought to have similar functions, and an unknown protein is also thought to fulfil the same function in Thaumarchaeota.

The archaellum operon used to be historically known as fla (from "flagellum"), but in order to avoid confusion with the bacterial flagellum and to be consistent with the remaining nomenclature (archaellum, archaellins), it has been recently proposed to be renamed to arl (archaellin-related genes).[11] Consequently, the name of the genes is also different (e.g., flaJ is now arlJ). Therefore, in the specialised literature both nomenclatures can be found, with the arl nomenclature being increasingly more used since 2018.

Genetic analysis in different archaea revealed that each of these components is essential for assembly of the archaellum.[12][13][14][15][16] Whereas most of the fla-associated genes are generally found in Euryarchaeota, one or more of these genes are absent from the fla-operon in Crenarchaeota. The prepilin peptidase (called PibD in crenarchaeota and FlaK in euryarchaeota) is essential for the maturation of the archaellins and is generally encoded elsewhere on the chromosome.[17]

Functional characterization has been performed for ArlI, a Type II/IV secretion system ATPase super-family member[18] and PibD/FlaK.[17][19][20] FlaI forms a hexamer which hydrolyses ATP and most likely generates energy to assemble the archaellum and to power its rotation. PibD cleaves the N-terminus of the archaellins before they can be assembled. ArlH (PDB: 2DR3) has a RecA-like fold and inactive ATPase domains. ArlH and ArlJ are the two other core components that together with ArlI form a core platform/motor. ArlX acts as a scaffold around the motor in Crenarchaeota.[21] ArlF and ArlG are potentially part of the stator of the archaellum motor; ArlF binds the S-layer, and ArlG forms filaments that seem to be "capped" by ArlF. Therefore, these two proteins potentially act together to attach the motor complex to the S-layer and to provide a rigid structure against which the rotating components of the motor - likely ArlJ - can rotate.[22][23]

The genes coding for arlC, arlD, and arlE are only present in Euryarchaeota and interact with chemotaxis proteins (e.g., CheY, CheD and CheC2, and the archaea-specific CheF) to sense environmental signals (such as exposure to light of specific wavelength, nutrient conditions etc.).[24][25]

Structure and assembly: type IV pilus (T4P) and archaellum

In the 1980s, Dieter Oesterhelt’s laboratory showed for the first time that haloarchaea switch the rotation of their archaellum from clockwise to counterclockwise upon blue light pulses.[26][27] This led microbiologists to believe that the archaeal motility structure is not only functionally, but also structurally reminiscent of bacterial flagella. Nevertheless, evidence started to build up indicating that archaella and flagella shared their function, but not their structure and evolutionary history. For example, in contrast to flagellins, archaellins (the protein monomers which form the archaellum filament) are produced as preproteins which are processed by a specific peptidase prior to assembly. Their signal peptide is homologous to class III signal peptides of type IV prepilins that are processed in Gram-negative bacteria by the peptidase PilD.[28] In Crenarchaeota PibD and in euryarchaeota FlaK are PilD homologs, which are essential for the maturation of the archaellins. Furthermore, archaellins are N-glycosylated[29][30] which has not been described for bacterial flagellins, where O-linked glycosylation is evident.

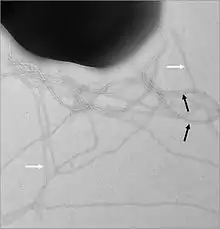

Another stark difference between the archaellum and the flagellum is the diameter of their filaments. While the bacterial flagellum is hollow, which allows flagellin monomers to travel through its interior to the tip of the growing filament, the archaellum filament is thinner, precluding the passage of archaellin monomers.[31][32][33][34][35] This evidence suggested that the mechanism of assembly of the archaellum is more similar to the assembly mechanism observed in type IV pili (in which the monomers assemble at the bottom of the growing filament) than the assembly mechanism of flagella via a type III secretion system.[36][37]

The similarities between archaella and T4P became more obvious with the identification of two archaella motor complex proteins that have homologues in T4P and type IV and II secretion systems. Specifically, ArlJ and ArlI are homologous to PilC and PilB/PilT, respectively. ArlJ is a membrane proteins for which little is structurally and functionally known, and ArlI is the only ATPase found in the archaellum operon, thus suggesting that this protein powers the assembly and the rotation of the filament.[38][7][18]

Functional analogs

Despite the limited number of details presently available regarding the structure and assembly of archaellum, it has become increasingly evident from multiple studies that archaella play important roles in a variety of cellular processes in archaea. In spite of the structural dissimilarities with the bacterial flagellum, the main function thus far attributed for archaellum is swimming in liquid[16][39][40] and semi-solid surfaces.[41][42] Increasing biochemical and biophysical information has further consolidated the early observations of archaella mediated swimming in archaea. Like the bacterial flagellum,[43][44] the archaellum also mediates surface attachment and cell-cell communication.[45][46] However, unlike the bacterial flagellum archaellum has not shown to play a role in archaeal biofilm formation.[47] In archaeal biofilms, the only proposed function is thus far during the dispersal phase of biofilm when archaeal cells escape the community using their archaellum to further initiate the next round of biofilm formation. Also, archaellum have been found to be able to have a metal-binding site.[31]

References

- In some species, the names are given as FlgA and FlgB.

- Albers SV, Jarrell KF (27 January 2015). "The archaellum: how Archaea swim". Frontiers in Microbiology. 6: 23. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00023. PMC 4307647. PMID 25699024.

- Wang F, Cvirkaite-Krupovic V, Kreutzberger MA, Su Z, de Oliveira GA, Osinski T, et al. (August 2019). "An extensively glycosylated archaeal pilus survives extreme conditions". Nature Microbiology. 4 (8): 1401–1410. doi:10.1038/s41564-019-0458-x. PMC 6656605. PMID 31110358.

- Woese CR, Fox GE (November 1977). "Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: the primary kingdoms". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 74 (11): 5088–90. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.5088W. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.11.5088. PMC 432104. PMID 270744.

- Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML (June 1990). "Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (12): 4576–9. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4576W. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMC 54159. PMID 2112744.

- Peabody CR, Chung YJ, Yen MR, Vidal-Ingigliardi D, Pugsley AP, Saier MH (November 2003). "Type II protein secretion and its relationship to bacterial type IV pili and archaeal flagella". Microbiology. 149 (Pt 11): 3051–3072. doi:10.1099/mic.0.26364-0. PMID 14600218.

- Pohlschroder M, Ghosh A, Tripepi M, Albers SV (June 2011). "Archaeal type IV pilus-like structures--evolutionarily conserved prokaryotic surface organelles". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 14 (3): 357–63. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2011.03.002. PMID 21482178.

- Ghosh A, Albers SV (January 2011). "Assembly and function of the archaeal flagellum". Biochemical Society Transactions. 39 (1): 64–9. doi:10.1042/BST0390064. PMID 21265748.

- Craig L, Pique ME, Tainer JA (May 2004). "Type IV pilus structure and bacterial pathogenicity". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 2 (5): 363–78. doi:10.1038/nrmicro885. PMID 15100690. S2CID 10654430.

- Craig L, Li J (April 2008). "Type IV pili: paradoxes in form and function". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 18 (2): 267–77. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2007.12.009. PMC 2442734. PMID 18249533.

- Jarrell KF, Albers SV (July 2012). "The archaellum: an old motility structure with a new name". Trends in Microbiology. 20 (7): 307–12. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2012.04.007. PMID 22613456.

- Pohlschroder M, Pfeiffer F, Schulze S, Abdul Halim MF (September 2018). "Archaeal cell surface biogenesis". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 42 (5): 694–717. doi:10.1093/femsre/fuy027. PMC 6098224. PMID 29912330.

- Patenge N, Berendes A, Engelhardt H, Schuster SC, Oesterhelt D (August 2001). "The fla gene cluster is involved in the biogenesis of flagella in Halobacterium salinarum". Molecular Microbiology. 41 (3): 653–63. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02542.x. PMID 11532133.

- Thomas NA, Bardy SL, Jarrell KF (April 2001). "The archaeal flagellum: a different kind of prokaryotic motility structure". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 25 (2): 147–74. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00575.x. PMID 11250034.

- Thomas NA, Mueller S, Klein A, Jarrell KF (November 2002). "Mutants in flaI and flaJ of the archaeon Methanococcus voltae are deficient in flagellum assembly". Molecular Microbiology. 46 (3): 879–87. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03220.x. PMID 12410843.

- Chaban B, Ng SY, Kanbe M, Saltzman I, Nimmo G, Aizawa S, Jarrell KF (November 2007). "Systematic deletion analyses of the fla genes in the flagella operon identify several genes essential for proper assembly and function of flagella in the archaeon, Methanococcus maripaludis". Molecular Microbiology. 66 (3): 596–609. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05913.x. PMID 17887963.

- Lassak K, Neiner T, Ghosh A, Klingl A, Wirth R, Albers SV (January 2012). "Molecular analysis of the crenarchaeal flagellum". Molecular Microbiology. 83 (1): 110–24. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07916.x. PMID 22081969.

- Bardy SL, Jarrell KF (November 2003). "Cleavage of preflagellins by an aspartic acid signal peptidase is essential for flagellation in the archaeon Methanococcus voltae". Molecular Microbiology. 50 (4): 1339–47. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03758.x. PMID 14622420.

- Ghosh A, Hartung S, van der Does C, Tainer JA, Albers SV (July 2011). "Archaeal flagellar ATPase motor shows ATP-dependent hexameric assembly and activity stimulation by specific lipid binding". The Biochemical Journal. 437 (1): 43–52. doi:10.1042/BJ20110410. PMC 3213642. PMID 21506936.

- Bardy SL, Jarrell KF (February 2002). "FlaK of the archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis possesses preflagellin peptidase activity". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 208 (1): 53–9. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11060.x. PMID 11934494.

- Szabó Z, Stahl AO, Albers SV, Kissinger JC, Driessen AJ, Pohlschröder M (February 2007). "Identification of diverse archaeal proteins with class III signal peptides cleaved by distinct archaeal prepilin peptidases". Journal of Bacteriology. 189 (3): 772–8. doi:10.1128/JB.01547-06. PMC 1797317. PMID 17114255.

- Albers SV, Jarrell KF (April 2018). "The Archaellum: An Update on the Unique Archaeal Motility Structure". Trends in Microbiology. 26 (4): 351–362. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2018.01.004. PMID 29452953.

- Banerjee A, Tsai CL, Chaudhury P, Tripp P, Arvai AS, Ishida JP, et al. (May 2015). "FlaF Is a β-Sandwich Protein that Anchors the Archaellum in the Archaeal Cell Envelope by Binding the S-Layer Protein". Structure. 23 (5): 863–872. doi:10.1016/j.str.2015.03.001. PMC 4425475. PMID 25865246.

- Tsai CL, Tripp P, Sivabalasarma S, Zhang C, Rodriguez-Franco M, Wipfler RL, et al. (January 2020). "The structure of the periplasmic FlaG-FlaF complex and its essential role for archaellar swimming motility". Nature Microbiology. 5 (1): 216–225. doi:10.1038/s41564-019-0622-3. PMC 6952060. PMID 31844299.

- Schlesner M, Miller A, Streif S, Staudinger WF, Müller J, Scheffer B, et al. (March 2009). "Identification of Archaea-specific chemotaxis proteins which interact with the flagellar apparatus". BMC Microbiology. 9: 56. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-9-56. PMC 2666748. PMID 19291314.

- Quax TE, Albers SV, Pfeiffer F (December 2018). Robinson NP (ed.). "Taxis in archaea". Emerging Topics in Life Sciences. 2 (4): 535–46. doi:10.1042/ETLS20180089. ISSN 2397-8554. PMC 7289035.

- Alam M, Oesterhelt D (July 1984). "Morphology, function and isolation of halobacterial flagella". Journal of Molecular Biology. 176 (4): 459–75. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(84)90172-4. PMID 6748081.

- Marwan W, Alam M, Oesterhelt D (March 1991). "Rotation and switching of the flagellar motor assembly in Halobacterium halobium". Journal of Bacteriology. 173 (6): 1971–7. doi:10.1128/jb.173.6.1971-1977.1991. PMC 207729. PMID 2002000.

- Faguy DM, Jarrell KF, Kuzio J, Kalmokoff ML (January 1994). "Molecular analysis of archael flagellins: similarity to the type IV pilin-transport superfamily widespread in bacteria". Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 40 (1): 67–71. doi:10.1139/m94-011. PMID 7908603.

- Jarrell KF, Jones GM, Kandiba L, Nair DB, Eichler J (July 2010). "S-layer glycoproteins and flagellins: reporters of archaeal posttranslational modifications". Archaea. 2010: 1–13. doi:10.1155/2010/612948. PMC 2913515. PMID 20721273.

- Meyer BH, Zolghadr B, Peyfoon E, Pabst M, Panico M, Morris HR, et al. (December 2011). "Sulfoquinovose synthase - an important enzyme in the N-glycosylation pathway of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius". Molecular Microbiology. 82 (5): 1150–63. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07875.x. PMC 4391026. PMID 22059775.

- Meshcheryakov VA, Shibata S, Schreiber MT, Villar-Briones A, Jarrell KF, Aizawa SI, Wolf M (May 2019). "High-resolution archaellum structure reveals a conserved metal-binding site". EMBO Reports. 20 (5). doi:10.15252/embr.201846340. PMC 6500986. PMID 30898768.

- Cohen-Krausz S, Trachtenberg S (August 2002). "The structure of the archeabacterial flagellar filament of the extreme halophile Halobacterium salinarum R1M1 and its relation to eubacterial flagellar filaments and type IV pili". Journal of Molecular Biology. 321 (3): 383–95. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00616-2. PMID 12162953.

- Poweleit N, Ge P, Nguyen HH, Loo RR, Gunsalus RP, Zhou ZH (December 2016). "CryoEM structure of the Methanospirillum hungatei archaellum reveals structural features distinct from the bacterial flagellum and type IV pilus". Nature Microbiology. 2 (3): 16222. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.222. PMC 5695567. PMID 27922015.

- Trachtenberg S, Galkin VE, Egelman EH (February 2005). "Refining the structure of the Halobacterium salinarum flagellar filament using the iterative helical real space reconstruction method: insights into polymorphism". Journal of Molecular Biology. 346 (3): 665–76. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.010. PMID 15713454.

- Trachtenberg S, Cohen-Krausz S (2006). "The archaeabacterial flagellar filament: a bacterial propeller with a pilus-like structure". Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology. 11 (3–5): 208–20. doi:10.1159/000094055. PMID 16983196. S2CID 21962186.

- Macnab RM (1992). "Genetics and biogenesis of bacterial flagella". Annual Review of Genetics. 26: 131–58. doi:10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.001023. PMID 1482109.

- Jarrell KF, Bayley DP, Kostyukova AS (September 1996). "The archaeal flagellum: a unique motility structure". Journal of Bacteriology. 178 (17): 5057–64. doi:10.1128/JB.178.17.5057-5064.1996. PMC 178298. PMID 8752319.

- Reindl S, Ghosh A, Williams GJ, Lassak K, Neiner T, Henche AL, et al. (March 2013). "Insights into FlaI functions in archaeal motor assembly and motility from structures, conformations, and genetics". Molecular Cell. 49 (6): 1069–82. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.014. PMC 3615136. PMID 23416110.

- Alam M, Claviez M, Oesterhelt D, Kessel M (December 1984). "Flagella and motility behaviour of square bacteria". The EMBO Journal. 3 (12): 2899–903. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02229.x. PMC 557786. PMID 6526006.

- Herzog B, Wirth R (March 2012). "Swimming behavior of selected species of Archaea". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 78 (6): 1670–4. doi:10.1128/AEM.06723-11. PMC 3298134. PMID 22247169.

- Szabó Z, Sani M, Groeneveld M, Zolghadr B, Schelert J, Albers SV, et al. (June 2007). "Flagellar motility and structure in the hyperthermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus". Journal of Bacteriology. 189 (11): 4305–9. doi:10.1128/JB.00042-07. PMC 1913377. PMID 17416662.

- Jarrell KF, Bayley DP, Florian V, Klein A (May 1996). "Isolation and characterization of insertional mutations in flagellin genes in the archaeon Methanococcus voltae". Molecular Microbiology. 20 (3): 657–66. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5371058.x. PMID 8736544.

- Henrichsen J (December 1972). "Bacterial surface translocation: a survey and a classification". Bacteriological Reviews. 36 (4): 478–503. doi:10.1128/MMBR.36.4.478-503.1972. PMC 408329. PMID 4631369.

- Jarrell KF, McBride MJ (June 2008). "The surprisingly diverse ways that prokaryotes move". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 6 (6): 466–76. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1900. PMID 18461074.

- Näther DJ, Rachel R, Wanner G, Wirth R (October 2006). "Flagella of Pyrococcus furiosus: multifunctional organelles, made for swimming, adhesion to various surfaces, and cell-cell contacts". Journal of Bacteriology. 188 (19): 6915–23. doi:10.1128/JB.00527-06. PMC 1595509. PMID 16980494.

- Zolghadr B, Klingl A, Koerdt A, Driessen AJ, Rachel R, Albers SV (January 2010). "Appendage-mediated surface adherence of Sulfolobus solfataricus". Journal of Bacteriology. 192 (1): 104–10. doi:10.1128/JB.01061-09. PMC 2798249. PMID 19854908.

- Koerdt A, Gödeke J, Berger J, Thormann KM, Albers SV (November 2010). "Crenarchaeal biofilm formation under extreme conditions". PLOS ONE. 5 (11): e14104. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...514104K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014104. PMC 2991349. PMID 21124788.