Chromoplast

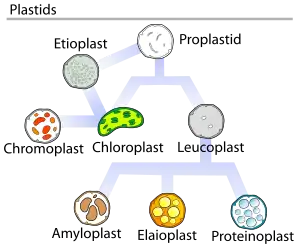

Chromoplasts are plastids, heterogeneous organelles responsible for pigment synthesis and storage in specific photosynthetic eukaryotes.[1] It is thought that like all other plastids including chloroplasts and leucoplasts they are descended from symbiotic prokaryotes.[2]

Function

Chromoplasts are found in fruits, flowers, roots, and stressed and aging leaves, and are responsible for their distinctive colors. This is always associated with a massive increase in the accumulation of carotenoid pigments. The conversion of chloroplasts to chromoplasts in ripening is a classic example.

They are generally found in mature tissues and are derived from preexisting mature plastids. Fruits and flowers are the most common structures for the biosynthesis of carotenoids, although other reactions occur there as well including the synthesis of sugars, starches, lipids, aromatic compounds, vitamins, and hormones.[3] The DNA in chloroplasts and chromoplasts is identical.[2] One subtle difference in DNA was found after a liquid chromatography analysis of tomato chromoplasts was conducted, revealing increased cytosine methylation.[3]

Chromoplasts synthesize and store pigments such as orange carotene, yellow xanthophylls, and various other red pigments. As such, their color varies depending on what pigment they contain. The main evolutionary purpose of chromoplasts is probably to attract pollinators or eaters of colored fruits, which help disperse seeds. However, they are also found in roots such as carrots and sweet potatoes. They allow the accumulation of large quantities of water-insoluble compounds in otherwise watery parts of plants.

When leaves change color in the autumn, it is due to the loss of green chlorophyll, which unmasks preexisting carotenoids. In this case, relatively little new carotenoid is produced—the change in plastid pigments associated with leaf senescence is somewhat different from the active conversion to chromoplasts observed in fruit and flowers.

There are some species of flowering plants that contain little to no carotenoids. In such cases, there are plastids present within the petals that closely resemble chromoplasts and are sometimes visually indistinguishable. Anthocyanins and flavonoids located in the cell vacuoles are responsible for other colors of pigment.[1]

The term "chromoplast" is occasionally used to include any plastid that has pigment, mostly to emphasize the difference between them and the various types of leucoplasts, plastids that have no pigments. In this sense, chloroplasts are a specific type of chromoplast. Still, "chromoplast" is more often used to denote plastids with pigments other than chlorophyll.

Structure and classification

Using a light microscope chromoplasts can be differentiated and are classified into four main types. The first type is composed of proteic stroma with granules. The second is composed of protein crystals and amorphous pigment granules. The third type is composed of protein and pigment crystals. The fourth type is a chromoplast which only contains crystals. An electron microscope reveals even more, allowing for the identification of substructures such as globules, crystals, membranes, fibrils and tubules. The substructures found in chromoplasts are not found in the mature plastid that it divided from.[2]

The presence, frequency and identification of substructures using an electron microscope has led to further classification, dividing chromoplasts into five main categories: Globular chromoplasts, crystalline chromoplasts, fibrillar chromoplasts, tubular chromoplasts and membranous chromoplasts.[2] It has also been found that different types of chromoplasts can coexist in the same organ.[3] Some examples of plants in the various categories include mangoes, which have globular chromoplasts, and carrots which have crystalline chromoplasts.[4]

Although some chromoplasts are easily categorized, others have characteristics from multiple categories that make them hard to place. Tomatoes accumulate carotenoids, mainly lycopene crystalloids in membrane-shaped structures, which could place them in either the crystalline or membranous category.[3]

Evolution

Plastids are descendants of cyanobacteria, photosynthetic prokaryotes, which integrated themselves into the eukaryotic ancestor of algae and plants, forming an endosymbiotic relationship. The ancestors of plastids diversified into a variety of plastid types, including chromoplasts.[3] Plastids also possess their own small genome and some have the ability to produce a percentage of their own proteins.

The main evolutionary purpose of chromoplasts is to attract animals and insects to pollinate their flowers and disperse their seeds. The bright colors often produced by chromoplasts is one of many ways to achieve this. Many plants have evolved symbiotic relationships with a single pollinator. Color can be a very important factor in determining which pollinators visit a flower, as specific colors attract specific pollinators. White flowers tend to attract beetles, bees are most often attracted to violet and blue flowers, and butterflies are often attracted to warmer colors like yellows and oranges.[5]

Research

Chromoplasts are not widely studied and are rarely the main focus of scientific research. They often play a role in research on the tomato plant (Solanum lycopersicum). Lycopene is responsible for the red color of a ripe fruit in the cultivated tomato, while the yellow color of the flowers is due to xanthophylls violaxanthin and neoxanthin.[6]

Carotenoid biosynthesis occurs in both chromoplasts and chloroplasts. In the chromoplasts of tomato flowers, carotenoid synthesis is regulated by the genes Psyl, Pds, Lcy-b, and Cyc-b. These genes, in addition to others, are responsible for the formation of carotenoids in organs and structures. For example, the Lcy-e gene is highly expressed in leaves, which results in the production of the carotenoid lutein.[6]

White flowers are caused by a recessive allele in tomato plants. They are less desirable in cultivated crops because they have a lower pollination rate. In one study, it was found that chromoplasts are still present in white flowers. The lack of yellow pigment in their petals and anthers is due to a mutation in the CrtR-b2 gene which disrupts the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway.[6]

The entire process of chromoplast formation is not yet completely understood on the molecular level. However, electron microscopy has revealed part of the transformation from chloroplast to chromoplast. The transformation starts with remodeling of the internal membrane system with the lysis of the intergranal thylakoids and the grana. New membrane systems form in organized membrane complexes called thylakoid plexus. The new membranes are the site of the formation of carotenoid crystals. These newly synthesized membranes do not come from the thylakoids, but rather from vesicles generated from the inner membrane of the plastid. The most obvious biochemical change would be the downregulation of photosynthetic gene expression which results in the loss of chlorophyll and stops photosynthetic activity.[3]

In oranges, the synthesis of carotenoids and the disappearance of chlorophyll causes the color of the fruit to change from green to yellow. The orange color is often added artificially—light yellow-orange is the natural color created by the actual chromoplasts.[7]

Valencia oranges Citris sinensis L are a cultivated orange grown extensively in the state of Florida. In the winter, Valencia oranges reach their optimum orange-rind color while reverting to a green color in the spring and summer. While it was originally thought that chromoplasts were the final stage of plastid development, in 1966 it was proved that chromoplasts can revert to chloroplasts, which causes the oranges to turn back to green.[7]

Compare

References

- Whatley JM, Whatley FR (1987). "When is a Chromoplast". New Phytologist. 106 (4): 667–678. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1987.tb00167.x.

- Camara B, Hugueney P, Bouvier F, Kuntz M, Monéger R (1995). Biochemistry and molecular biology of chromoplast development. Int. Rev. Cytol. International Review of Cytology. 163. pp. 175–247. doi:10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62211-1. ISBN 9780123645678. PMID 8522420.

- Egea I, Barsan C, Bian W, Purgatto E, Latché A, Chervin C, Bouzayen M, Pech JC (October 2010). "Chromoplast differentiation: current status and perspectives". Plant & Cell Physiology. 51 (10): 1601–11. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcq136. PMID 20801922.

- Vasquez-Caicedo AL, Heller A, Neidhart S, Carle R (August 2006). "Chromoplast morphology and beta-carotene accumulation during postharvest ripening of Mango Cv. 'Tommy Atkins'". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 54 (16): 5769–76. doi:10.1021/jf060747u. PMID 16881676.

- Waser NM, Chittka L, Price MV, Williams NM, Ollerton J (June 1996). "Generalization in Pollination Systems, and Why it Matters". Ecology. 77 (4): 1043–60. doi:10.2307/2265575. JSTOR 2265575.

- Galpaz N, Ronen G, Khalfa Z, Zamir D, Hirschberg J (August 2006). "A chromoplast-specific carotenoid biosynthesis pathway is revealed by cloning of the tomato white-flower locus". The Plant Cell. 18 (8): 1947–60. doi:10.1105/tpc.105.039966. PMC 1533990. PMID 16816137.

- Thomson WW (1966). "Ultrastructural Development of Chromoplasts in Valencia Oranges". Botanical Gazette. 127 (2–3): 133–9. doi:10.1086/336354. JSTOR 2472950.