Archie Jackson

Archibald Jackson (5 September 1909[1] – 16 February 1933), occasionally known as Archibald Alexander Jackson, was an Australian international cricketer who played eight Test matches as a specialist batsman between 1929 and 1931. A teenage prodigy, he played first grade cricket at only 15 years of age and was selected for New South Wales at 17. In 1929, aged 19, Jackson made his Test debut against England, scoring 164 runs in the first innings to become the youngest player to score a Test century.

.jpg.webp) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Archibald Jackson | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 5 September 1909 Rutherglen, Scotland | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 16 February 1933 (aged 23) Brisbane, Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting | Right-handed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling | Right-arm off spin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | Batsman | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test debut (cap 130) | 1 February 1929 v England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Test | 14 February 1931 v West Indies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic team information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1926–1930 | New South Wales | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: CricketArchive, 26 November 2007 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

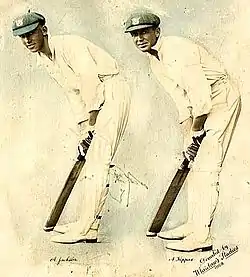

Renowned for his elegant batting style, he played in a manner similar to the great Australian batsmen Victor Trumper, and Alan Kippax, Jackson's friend and mentor. His Test and first-class career coincided with the early playing years of Don Bradman, with whom he was often compared. Before the two departed for England as part of the 1930 Australian team, some observers considered Jackson the better batsman, capable of opening the batting or coming in down the order. Jackson's career was dogged by poor health; illness and his unfamiliarity with local conditions hampered his tour of England, only playing two of the five Test matches. Later in the year, in the series against the West Indies, Jackson was successful in the first Test in Adelaide, scoring 70 not out before a poor run of form led to his omission from the fifth Test.

Early in the 1931–32 season, Jackson coughed blood and collapsed before the start of play in a Sheffield Shield match against Queensland. Subsequently, admitted to a sanatorium in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney, Jackson was diagnosed with tuberculosis. In an attempt to improve his health and to be closer to his girlfriend, Jackson moved to Brisbane. Ignoring medical advice, Jackson returned to cricket with a local team; however, his health continued to deteriorate and he died at the age of just 23. It is speculated that, had he lived, he may have rivalled Don Bradman as a batsman.[2]

Early life and career

Childhood

.jpg.webp)

Jackson, the first son and third child of Alexander and Margaret Jackson, was born in 1909 at Rutherglen, a small town near Glasgow in Scotland. His father had spent part of his childhood in Australia and returned with his family to settle in Balmain, a suburb of Sydney, in 1913.[3]

Raised as a Methodist, Jackson was a lifelong teetotaller and non-smoker. He attended Birchgrove Public and Rozelle Junior Technical schools and represented New South Wales Schoolboys at football and cricket.[4] Football talent ran in the family: his uncle Jimmy and cousins Archie and James were professional footballers in Scotland and England, the latter captaining Liverpool.[5][6]

Growing up near the home ground of Balmain District Cricket Club, Jackson joined the club in his mid-teens where he quickly came to the attention of the captain, Test bowler Arthur Mailey.[7] The Labor politician "Doc" Evatt, a noted benefactor of young cricketers, helped Jackson's career by purchasing suitable cricket equipment for him.[4] At the age of 15 years and one month, he made his first grade début for Balmain; cricket historian David Frith believes that Jackson is the youngest cricketer to play at this level.[8]

Jackson left school at this time and worked for a warehouse firm called Jackson & McDonald (unrelated) until the demands of cricket compelled him to resign.[9] The Test batsman Alan Kippax employed Jackson in his sporting goods store and became his mentor.[9] In 1925–26, his second season with Balmain, Jackson led the grade cricket competition's batting averages and won selection for the New South Wales Second XI to play Victoria.[10]

Selection for New South Wales

Jackson began the 1926–27 season with scores of 111 against St George, 198 against Western Suburbs and 106 against Mosman. As a result, he made his first-class début for New South Wales (NSW) against Queensland at Brisbane and scored 86 in the second innings.[11] He posted a century in the return match against the Queenslanders at the SCG. On NSW's tour of the southern states, Jackson made a century in a non first-class fixture against Northern Tasmania and then hit 104 not out against South Australia.[12] These performances prompted the former Australian captain Clem Hill to describe Jackson as "... the biggest find since Ponsford."[13]

No Test matches were scheduled for 1927–28, although the New Zealand team briefly toured Australia on their return journey from playing in England. Jackson scored 104 against the visiting side and shared a century partnership with Kippax, scored in just over 30 minutes.[14] After a brief run of low scores, a boil on Jackson's knee forced his withdrawal from the match against South Australia at Adelaide. His replacement was another rising teenage batsman, Donald Bradman, who made his first-class début in the match. On his return to the team, Jackson was promoted to open the batting and scored a century in both innings in the return match against South Australia.[15] At the end of the season, he toured New Zealand with an Australian second XI, while Bradman missed out. The side consisted of a few established Test players mixed with promising youngsters.[16] Australia were unbeaten on the tour and Jackson scored 198 runs in four matches at an average of 49.50.[17]

Test cricket

.jpg.webp)

Test selection

During the 1928–29 season, a strong England team captained by Percy Chapman toured Australia for a five-Test Ashes series.[18] Seeking selection in the Australian Test side, Jackson failed twice in a match designated as a Test trial in Melbourne.[19] In the next match, against the English for New South Wales, he scored 4 and 40 while his teammates Bradman and Kippax both made centuries. Both Bradman and Kippax were selected for the First Test at the Brisbane Exhibition Ground, Jackson missed out.[20] Keeping his name in front of the selectors, he scored 162 and 90 against South Australia.[21] After Australia lost the first three Tests and the Ashes, the selectors gave Jackson his opportunity, selecting him for his Test début in the fourth Test at the Adelaide Oval.[22] Arthur Mailey, his club captain and the only other Test player from Balmain CC to that time, ran from his office at the Sydney Sun to Kippax's sports store in Martin Place to tell Jackson the good news.[23]

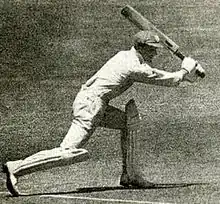

England batted first and made 334. In reply, Jackson opened the batting with Bill Woodfull.[24] Before the Test, the Australian skipper, Jack Ryder, approached Kippax for his opinion about such a young player as Jackson being given the responsibility of opening the batting. Kippax replied, "I am sure he expects to open."[23] After Australia lost three wickets for 19 runs, Ryder joined Jackson at the wicket. Playing in an unhurried manner, Jackson looked confident against the pace of Harold Larwood and punished Maurice Tate when his bowling strayed down the leg side. In 105 minutes, Jackson and Ryder added 100 runs. Jackson reached his half century, followed by Ryder and at stumps on the second day, Australia's total was 3/131.[24]

The exertion had left Jackson exhausted. His teammate "Stork" Hendry said that Jackson was limp when he returned to the dressing room. "We had to mop him with cold towels", he said.[25] Early the next day, Ryder was dismissed and Jackson was joined by Bradman. The two young batsmen shared a long partnership, with Jackson on 97 at the end of the session.[26] As they returned to the wicket after the interval, Bradman advised his younger colleague to play carefully to secure his century. Jackson made no reply, but responded by hitting the first ball from Larwood to the point boundary for four runs, the ball rebounding back on to the field in front of a cheering crowd in the Members' Stand.[27] After this, he cut loose, with deft glances from the faster balls and cut shots reminiscent of Charlie Macartney.[28] Jackson was eventually dismissed for 164, making him the youngest Australian batsman to score a Test century, a record beaten by Neil Harvey in 1948.[29] It is still the second highest score on Test début by an Australian, only one run fewer than Charles Bannerman's 165 not out in the first-ever Test in 1877.[30] This innings saw Jackson hailed as a national hero and he was showered with tributes including a public meeting called in his honour by the Mayor of Balmain.[31]

In 1929–30, ill-health restricted Jackson to just five first-class matches and five innings for Balmain. Despite his health, Jackson had a successful season, and scored 168 not out against Arthur Gilligan's English team, which toured Australia briefly en route to New Zealand. He was seen as an automatic selection for the 1930 Ashes tour of England.[32] He confirmed his selection with 182 in a Test trial, an innings regarded by many as the best he had ever played.[33] Another scare with illness saw him hospitalised in Adelaide after the Christmas match against South Australia, missing the next two state matches.[34] His health problems continued after an operation to remove his tonsils; a procedure that was arranged by the Australian Board of Control despite Jackson never having previously suffered any problems with his tonsils. Bill Ponsford had suffered from tonsillitis during the previous tour and the Board were anxious to avoid similar occurrences. Complications resulting from the operation saw Jackson lose a stone (6.4 kilograms) in weight.[34]

Ashes tour of England

Jackson was included in the Australian squad to tour England in 1930. The bonus for Australia from England's 1928–29 visit was the emergence of Jackson and Don Bradman[35] and now much was expected of them in a rebuilt Australian squad that retained only four players from the 1926 tour of England.[36] But Jackson was frequently ill and his unfamiliarity with English pitches resulted in patchy form.[37] Even so, he was described at the time by former England player Cecil Parkin as, "a better bat than Bradman".[38] He was left out of the team for the First Test at Trent Bridge, the only defeat suffered by the Australians all tour.[39] After the Second Test at Lord's, Jackson recovered some form. Ponsford and Fairfax both fell ill and as a result Jackson was included in the team for the Third Test at Leeds. He scored one run in his only innings while Bradman made a then-record Test score of 334.[40] Jackson was omitted for the Fourth Test, but a century against Somerset helped him to force his way back into the side for the Fifth and deciding Test at The Oval.[2][41]

In this match Jackson, batting down the order, played a brave innings on a dangerous wicket facing hostile bowling from Larwood. He took repeated blows on the body while scoring a valuable 73 runs.[2] He shared a stand of 243 with Bradman, who scored 232, and Australia won the Test by an innings and 39 runs to regain The Ashes.[41] Overall, Jackson's tour was modest, scoring 1,097 runs at an average of 34.28 with only one hundred, made against Somerset.[42] Wisden Cricketers' Almanack, in its report on the 1930 Australians, described Jackson as the "... great disappointment of the team ... with [his] well-deserved reputation for grace of style ... at no time did people in England see the real Jackson."[43]

On return to Australia for the 1930–31 season, Jackson was selected for the first four Tests against the West Indies. After scoring 70 not out in the First Test in Adelaide, his form tapered away and managed only 124 runs at an average of 31.00 for the first four Tests, resulting in his omission for the Fifth and final Test in Sydney.[44][45] In Jackson's absence, the West Indies defeated Australia for the first time in a Test. The West Indies captain Jackie Grant, in a daring move, declared his team's innings closed twice in order to catch the home team on a "sticky wicket".[46] Jackson, in his capacity as twelfth man, came in as a runner for an injured batsman on the final afternoon, making what was to be his final appearance in first-class cricket.[47]

It was during this Australian season, during a match in Brisbane, that Jackson was introduced to Phyllis Thomas, a trained ballet dancer, who later became his fiancée.[48] In March 1931, Jackson felt his health had recovered sufficiently to join an exhibition tour of Far North Queensland, led by Alan Kippax. He found the tour exhausting, with arduous travel and damp weather, but played well enough to top the aggregate with over 1,100 runs at an average of 93.00. In a letter to his childhood friend and New South Wales teammate, Bill Hunt, he wrote, "Our tour of North Queensland has now concluded and thank goodness! ... I would never make this trip again unless I was guaranteed £100, and that's not enough!"[49]

Illness and death

.jpg.webp)

Jackson began the 1931–32 season in form and seemingly in good health, scoring 183 for Balmain in grade cricket against Gordon.[50] He was selected for the NSW team to play Queensland in Brisbane. Before the match commenced, Jackson collapsed after coughing up blood and was rushed to hospital. Jackson believed he was suffering from influenza and he was discharged after five days, when he returned to Sydney.[51] Within a week of his return, the Board of Control arranged for Jackson to be admitted to a sanatorium at Wentworth Falls in the Blue Mountains. After a few months at the sanatorium, Jackson moved into a cottage at nearby Leura to be cared for by his sister.[52]

Tuberculosis

Seeking treatment for psoriasis, Jackson travelled to Adelaide in July 1932. During his time there, he felt well enough to have an occasional training session in the nets.[53] At the same time, a confidential report was sent to the New South Wales Cricket Association confirming that Jackson had, "... pneumonary tuberculosis with fairly extensive involvement of the lungs."[54] He returned to Leura and made plans to move to Brisbane, in the belief that the warmer climate would aid his recovery and to be closer to Phyllis.[54]

In Brisbane, Jackson offered his services to grade club Northern Suburbs, against the advice of his doctors. Despite suffering from a chronic shortness of breath, he averaged 159.66 over seven innings and drew record crowds to the club's matches.[55] The media and public were keen to see him selected for the early tour matches against the touring English team; however, medical advice prevented his inclusion.[56] Jackson took work as a sales assistant at a sports depot and wrote a column for the Brisbane Mail. He wrote extensively on the Bodyline tactics employed by the English team during the summer. Jackson insisted that Bodyline was legitimate, held no threat to the game, and that it could be combatted—a minority view in Australia at that time.[57]

Death

.jpg.webp)

In early February 1933, Jackson collapsed after playing cricket and was admitted to hospital. Aware of the serious nature of his illness and the possibility of his death, Jackson and Phyllis announced their engagement.[58] As the Brisbane Test between Australia and England began, Jackson suffered a severe pulmonary hemorrhage. His parents made their way to Brisbane to see him and many members of the English and Australian teams visited him in hospital during his last days.[59] On 16 February 1933, Jackson became the youngest Test cricketer to die until Manjural Rana in 2007.[60]

Jackson's body was transported back to Sydney by train, which also carried the Australia and England teams for the next Test. Thousands of mourners lined the streets of Sydney for his funeral and the pallbearers were Woodfull, Ponsford, McCabe, Bert Oldfield, Vic Richardson and Bradman.[2] He was buried at the Field of Mars cemetery and a public subscription was raised to install a headstone on his gravesite. The headstone, reading simply He played the game, was unveiled by the Premier of New South Wales Bertram Stevens.[61]

Style

Jackson was seen as a stylish and elegant batsman, with a genius for timing and placement.[62] His footwork was light and his supple wrists allowed him to steer the ball square and late. He held the bat high on the handle and his cover drive was executed with balletic grace.[62] He was seen as possessing the comely movement and keenness of eye of the great batsman of cricket's Golden Age, Victor Trumper.[63] Bradman described Jackson as "tall and slim, rather lethargic and graceful in his movements".[64] Jackson professed a love of applying the maximum velocity to the ball with a minimum of effort. His one identifiable fault was an occasional failing outside off-stump, being prone to unnecessarily dab at away-swingers and being caught in the slips cordon.[65]

His contemporaries noted his classical style. The journalist A.R.B. Palmer described his cover drive as "... perfectly balanced and true ... the bat seems a whip in his hands."[66] Clem Hill, the former Australian captain, noted Jackson's sparkling footwork, watching close enough to notice that his toes turned in as he walked.[13] Like Kippax, whose style was uncannily similar, Jackson wore his shirt-sleeves almost down to his wrists. This was not in imitation but to conceal the blemishes on his arms caused by psoriasis. Kippax was not seen by some as the best person to imitate, with Charles Kelleway critical of Jackson's flourishes, wishing he would not be so, "... cramped in copying other batsman's styles".[67]

Inevitably, he was compared to his New South Wales and Australian teammate, Bradman. In contrast to Jackson, Bradman made not even a pretence of being a stylist. A writer, comparing the two after Jackson's Test début, stated that Bradman had "forced his way to the top by sheer natural ability, a straight bat, cool cheerful temperament, determination and enterprise", but Jackson was "the finished batsman, the batsman who knows one stroke for each ball ... [and] executes that stroke with an artistry that has no parallel to this day".[68] Before the 1930 tour of England, experts such as Frank Woolley, Percy Fender and Maurice Tate rated Jackson as more likely to succeed in English conditions; Bradman was seen as too unorthodox or even cross-batted for softer English wickets.[69]

See also

Notes

- Shepherd, p. 51

- Williamson, Martin. "A better batsman than Bradman?", 2007-10-27, Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 29 December 2007. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

- Frith, p. 5.

- Nairn, Bede (2006). "Jackson, Archibald (Archie) (1909–1933)". Australian Dictionary of Biography, Online Edition. Australian National University. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- Oswald, Nick (1 February 2004). "Forgotten genius". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- Jimmy, Alex, Archie and The Parson, Scots Football Worldwide

- Frith, p. 8.

- Frith, p. 9.

- Frith, p. 10.

- Frith, p. 13.

- Frith, pp. 16–17.

- Frith, p. 20.

- Frith, p. 23.

- Frith, p. 25.

- Frith, pp. 26–27.

- Frith, p. 28.

- "Australia in New Zealand, Feb–Apr 1928: Tour Statistics". Cricinfo. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

- Frith, p. 34.

- Frith, p. 35.

- Frith, pp. 36–37.

- Frith, p. 37.

- Frith, pp. 38–39.

- Harte, pp. 314–315. The distance between the Sun building on Elizabeth St and Kippax's store was around 880 yards (800 m) or less.

- Frith, pp. 39–41.

- Roebuck, pp. 40–41.

- Frith, pp. 42–43.

- Bradman, p. 23.

- Frith, pp. 39–44.

- "Youngest player to score a hundred". Cricinfo Records. Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 28 October 2007. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

- "Hundred on debut". Cricinfo Records. Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- Frith, p. 45.

- Frith, pp. 53–57.

- "Jackson, Mr. Archibald". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack obituary. as published on Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 12 November 2007. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

- Frith, p. 58.

- Harte, p. 319.

- Wisden Cricketers' Almanack, 1931 edition, based on a view expressed by Neville Cardus in the Manchester Guardian. The four returning players were Grimmett, Oldfield, Ponsford and Woodfull.

- Frith, pp. 62–63.

- Frith, p. 64.

- Frith, pp. 65–66.

- Frith, pp. 66–67.

- "Fifth Test match England v Australia 1930". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack – as published on Cricinfo. John Wisden & Co. 1931. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- "First-class Batting and Fielding for Australians–Australia in England 1930". Cricket Archive. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- Southerton, S.J. (1931). "The Australian team in England 1930". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack–as published by Cricinfo. John Wisden and Co. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- "West Indies in Australia Nov 1930/Mar 1931 – Test Averages". Cricinfo. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

- Frith, pp. 80–81.

- Goodwin, p. 18.

- Frith, p. 81.

- Frith, p. 82.

- Frith, pp. 83–86.

- Frith, p. 87.

- Frith, p. 88.

- Frith, p. 89.

- Frith, p. 92.

- Frith, p. 93.

- Frith, p. 94.

- Frith, p. 96.

- Frith, pp. 96–100.

- Frith, p. 100.

- Frith, p. 101.

- "Shortest lived players". CricinfoRecords. Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 20 March 2007. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- Frith, pp. 105–106.

- Martin-Jenkins, pp. 191–192.

- Frith, p. 1.

- Bradman, p. 198.

- Frith, p. 18.

- Frith, p. 21.

- Frith, pp. 23–24.

- Williams, p. 37.

- Williams, p. 43.

References

- Bradman, Don (1994). Farewell to Cricket. Sydney: Editions Tom Thompson. ISBN 1-875892-01-X.

- Frith, David (1974). Archie Jackson: The Keats of Cricket. London: Pavilion. ISBN 1-85145-119-6.

- Goodwin, Clayton (1980). Caribbean Cricketers: From the Pioneers to Packer. London: Harrap & Co. ISBN 0-245-53458-X.

- Harte, Chris (1993). A History of Australian Cricket. Andre Deutsch. ISBN 0-233-98825-4.

- Martin-Jenkins, Christopher (1980). The Complete Who's Who of Test Cricketers. Adelaide: Rigby. ISBN 0-7270-1262-2.

- Roebuck, Peter (1990). Great Innings. Sydney: Pan. ISBN 0-7329-0359-9.

- Shepherd, Jim (1981). Winfield Book of Australian Sporting Records. Rigby. p. 51. ISBN 9780727015136.

- Williams, Charles (1996). Bradman: An Australian Hero. London: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-88097-3.

- Wisden Cricketers' Almanack (1931 ed.). London: Wisden.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Archie Jackson. |