Ashanti Traditional Buildings

The Asante Traditional Buildings are the only surviving examples of traditional Ashanti architecture.[1] To the north-east of Kumasi, these are the last material remains of the great Asante civilization, which reached its high point in the 18th century. Since the dwellings are made of earth, wood and straw, they are vulnerable to the onslaught of time and weather.[1] These buildings served mainly as palaces, shrines[2] houses for the powerful deities who protected the Kingdom, homes for the affluent, and finally, as mausoleums. And like all buildings of value, the structures were the result of the Asantes’ desire to achieve harmony on earth with their creator, the Supreme Being, through the mediation of the lesser deities.[3] One of these is the Ejisu Besease Shrine and it was spatially documented by the Zamani project in 2006.[4]

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

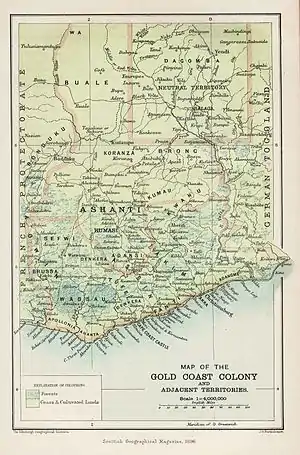

The Ashanti Empire and Gold Coast on a map from 1896. | |

| Location | Ghana |

| Criteria | Cultural: (v) |

| Reference | 35 |

| Inscription | 1980 (4th session) |

| Coordinates | 6°24′04″N 1°37′33″W |

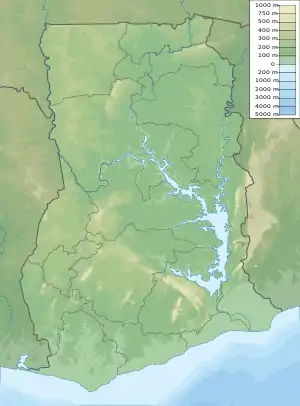

.svg.png.webp) Location of Ashanti Traditional Buildings in Earth  Ashanti Traditional Buildings (Ghana) | |

Location and value

The Asante Traditional Buildings are situated in ten different villages to the north and east of Kumasi in south-central Ghana.[5] They represent all that remains of the traditional shrine houses (Abosomfie) of the Ashanti people, each of which was traditionally regarded as the spiritual home of a particular Obosum, a minor deity who could mediate between a mortal being and the supreme god Nyame.[6] The buildings are located at: Abirim, Asawase, Asenemaso, Bodwease, Ejisu Besease, Adarko Jachie, Edwenase, Kentinkrono, Patakro and Saaman[1]

Design and construction

Their design and construction, consisting of a timber framework filled up with clay and thatched with sheaves of leaves, is rare nowadays. All designated sites are shrines, but there have been many other buildings in the past in the same architectural style. They have been best preserved in the villages, away from modern construction and warfare.[1]

The typical house, whether designed for human habitation or for the deities, normally consists of four separate rectangular single-room buildings set around an open courtyard; the inner corners of adjacent buildings are linked by means of splayed screen walls, whose sides and angles could be adapted to allow for any inaccuracy in the initial layout. Typically, three of the buildings are completely open to the courtyard, while the fourth is partially enclosed, either by a door and windows, or by open-work screens flanking an opening.[3]

Integrity

The group of buildings is the only surviving example of the Asante traditional architecture. Very few of the buildings are complete. In most cases parts of the original structures are missing. The integrity is threatened by deterioration of the fabric due to the warm humid tropical climate that is destructive of traditional earth and wattle-and-daub buildings. Heavy rainfall and high humidity encourage rapid mould formation on wall surfaces, and the activities of termites, and other prolifically breeding destructive insects. The intensification of agricultural developments makes the traditional building materials of thatch, bamboo, and specific timber species less easy to obtain.[7] Unfortunately, most of the masterpieces of the Asante indigenous architecture have been lost to the world, some due to warfare, especially during the 19th century, when the British destroyed most of the buildings with canons. But what really spelled the doom of the treasures of Asante heritage, was the irresistible socio-cultural and economic change of the 20th century, such as the phenomenal prosperity resulting from cocoa and gold trade and its attendant ‘modern life’. In the wake of this, ‘mud’ houses were replaced by houses made with ‘sandcrete’ blocks and corrugated aluminium.[3]

Protection and management requirements

Between 1960 and 1970 the buildings were acquired by the Ghana Museums and Monuments Board (GMMB) and scheduled as a National Monument under the Law of Ghana NLC Decree 387 of 1969. There is also involvement by the Chief and his Elders. Therefore, the instruments for the protection of the Asante Traditional Buildings operate on two levels. The first is a prescription of customary regulations, prohibitions and penalties that have been handed down through generations from the past. The second is the modern statutory regulations enacted by Government. The two sets of laws complement each other, and are a generally effective means of protection although the modes of enforcement are different.[1]

References

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Asante Traditional Buildings". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- Asante, Eric Appau; Kquofi, Steve; Larbi, Stephen (January 2015). "The symbolic significance of motifs on selected Asante religious temples". Journal of Aesthetics & Culture. 7 (1): 27006. doi:10.3402/jac.v7.27006. ISSN 2000-4214.

- "Ghana Museums & Monuments Board". www.ghanamuseums.org. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- "Site - Besease Shrine - Kumasi". zamaniproject.org. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Asante Traditional Buildings". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2020-05-13.

- "Asante Traditional Buildings (Ghana) | African World Heritage Sites". www.africanworldheritagesites.org. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- "Asante Traditional Buildings - World Heritage Site - Pictures, Info and Travel Reports". www.worldheritagesite.org. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

Bibliography

- Michael Swithenbank. Ahanti fetish houses. Accra Ghana Univ Press, 1969