Ashokan Prakrit

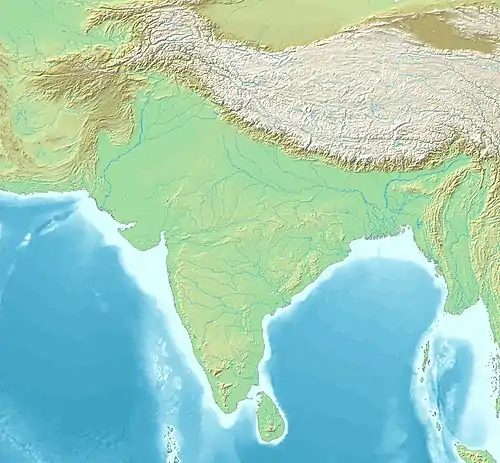

Ashokan Prakrit (or Aśokan Prākṛta) is the Middle Indo-Aryan dialect continuum used in the Edicts of Ashoka, attributed to Emperor Ashoka of the Mauryan Empire who reigned 268 BCE to 232 BCE.[1] The Edicts are inscriptions on monumental pillars and rocks throughout South Asia that cover Ashoka's conversion to Buddhism and espouse Buddhist principles (e.g. upholding dhamma and the practice of non-violence).

| Ashokan Prakrit | |

|---|---|

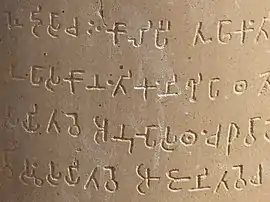

Ashokan Prakrit inscribed in the Brahmi script at Sarnath. | |

| Region | South Asia |

| Era | 268—232 BCE |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Brahmi, Kharoshthi | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

The Ashokan Prakrit dialects reflected local forms of the Early Middle-Indo-Aryan language. Three dialect areas are represented: Northwestern, Western, and Eastern. The Central dialect of Indo-Aryan is exceptionally not represented; instead, inscriptions of that area use the Eastern forms. [2]:50[1] Ashokan Prakrit is descended from an Old Indo-Aryan dialect closely related to Vedic Sanskrit, on occasion diverging by preserving archaisms from Proto-Indo-Aryan.

Ashokan Prakrit is attested in the Brahmi script and the Kharoshthi script (only in the Northwest).

Classification

Masica classifies Ashokan Prakrit as an Early Middle-Indo-Aryan language, representing the earliest stage after Old Indo-Aryan in the historical development of Indo-Aryan. Pali and early Jain Ardhamagadhi (but not all of it) also represent this stage.[2]:52

Dialects

There are three dialect groups attested in the Ashokan Edicts, based on phonological and grammatical idiosyncrasies which correspond with developments in later Middle Indo-Aryan languages:[3][4][5]

- Western: The inscriptions at Girnar and Sopara, which: prefer r over l; do not merge the nasal consonants (n, ñ, ṇ); merge all sibilants into s; prefer (c)ch as the reflex of the Old Indo-Aryan thorn cluster kṣ; have -o as the nominative singular of masculine a-stems, among other morphological peculiarities. Notably, this dialect corresponds well with Pali, the preferred Middle Indo-Aryan language of Buddhism.[6]:5

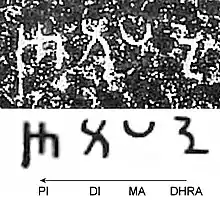

- Northwestern: The inscriptions at Shahbazgarhi and Mansehra written in the Kharosthi script: retain etymological r and l as distinct; do not merge the nasals; do not merge the sibilants (s, ś, ṣ); metathesis of liquids in consonant clusters (e.g. Sanskrit dharma > Shahbazgarhi dhrama). These features are shared with the modern Dardic languages.[7]

- Eastern: The standard administrative language, exemplified by the inscriptions at Dhauli and Jaugada and used in the geographical core of the Mauryan Empire: prefer l over r, merge the nasals into n (and geminate ṁn), prefer (k)kh as the reflex of OIA kṣ, have -e as the nominative singular of masculine a-stems, etc. Oberlies suggests that the inscriptions in the Central zone were translated from the "official" administrative forms of the Edicts.

Sample

The following is the first sentence of the Major Rock Edict 1, inscribed c. 257 BCE in many locations.[8]

- Girnar:

iy[aṃ]

this

dhaṃma-lipī

morality-rescript

Devānaṃpriyena

Devānāṁpriya.INS

Priyadasinā

Priyadarśin.INS

rāña

king.INS

lekhāpitā

write.CAUS.PTC

'This rescript on morality has been caused to be written by king Devānāṁpriya Priyadarśin.'

- Kalsi:

iyaṃ

this

dhaṃma-lipi

morality-rescript

Devānaṃpiyena

Devānāṁpriya.INS

Piyadas[i]nā

Priyadarśin.INS

[lekhit]ā

write.PTC

- Shahbazgarhi:

[aya]

this

dhrama-dipi

morality-rescript

Devanapriasa

Devānāṁpriya.GEN

raño

king.GEN

likhapitu

write.CAUS.PTC

- Mansehra:

ayi

this

dhra[ma]dip[i]

morality-rescript

Devanaṃ[priye]na

Devānāṁpriya.INS

Priya[draśina

Priyadarśin.INS

rajina

king.INS

li]khapita

write.CAUS.PTC

- Dhauli:

...

...

[si

LOC

pava]tasi

mountain.LOC

[D]e[v]ā[na]ṃp[iy]

Devānāṁpriya.INS

...

...

[nā

INS

lājina

king.INS

l]i[kha]

write.PTC

...

...

- Jaugada:

iyaṃ

this

dhaṃma-lipi

morality-rescript

Khepi[ṃ]galasi

Khepiṅgala.LOC

pavatasi

mountain.LOC

Devānaṃpiyena

Devānāṁpriya.INS

Piyadasinā

Priyadarśin.INS

lājinā

king.INS

likhāpitā

write.CAUS.PTC

The dialect groups and their differences are apparent: the Northwest retains clusters but does metathesis on liquids (dhrama vs. other dhaṃma) and retains an earlier form dipi "writing" borrowed from Iranian;[9] meanwhile, the l/r distinctions are apparent in the word for "king" (Girnar rāña but Jaugada lājinā).

References

- Thomas Oberlies. "Aśokan Prakrit and Pali". In George Cardona; Dhanesh Jain (eds.). The Indo-Aryan Languages. pp. 179–224.

- Masica, Colin (1993). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- Jules Bloch (1950). Les inscriptions d'Aśoka, traduites et commentées par Jules Bloch (in French).

- Ashwini Deo (2018). "Dialects in the Indo-Aryan landscape". In Charles Boberg; John Nerbonne; Dominic Watt (eds.). The Handbook of Dialectology (PDF). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (2007-07-26). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. p. 165.

- Norman, Kenneth Roy (1983). Pali Literature. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. pp. 2–3. ISBN 3-447-02285-X.

- George A. Grierson (1927). "On the Old North-Western Prakrit". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 4 (4): 849–852. JSTOR 25221256.

- "2. Girnār, Kālsī, Shāhbāzgaṛhī, Mānsehrā, Dhauli, Jaugaḍa rock edicts (Synoptic, Māgadhī and English)". Bibliotheca Polyglotta. University of Oslo.

- Hultzsch, E. (1925). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum v. 1: Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. xlii.