Asuka Langley Soryu

Asuka Langley Soryu (惣流・アスカ・ラングレー, Sōryū Asuka Rangurē, IPA: [soːɾʲɯː asɯ̥ka ɾaŋɡɯɾeː])[1] is a fictional character from the anime Neon Genesis Evangelion, created by Gainax. Within the series, she is designated as the Second Child and the pilot of a giant mecha named Evangelion Unit 02, in order to fight against enemies known as Angels for the special agency Nerv. Due to childhood trauma, she has developed a competitive and outgoing character, in an attempt to get noticed by other people and affirm her own self. Asuka is voiced by Yūko Miyamura in Japanese in all animated appearances and merchandise, while in English she is voiced by Tiffany Grant in the ADV Films dub and by Stephanie McKeon in the Netflix dub. She appears in the franchise's animated feature films and related media, video games, the original net animation Petit Eva: Evangelion@School, the Rebuild of Evangelion films, and the manga adaptation by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto. In the Rebuild of Evangelion films her Japanese surname is changed to Shikinami (式波).

| Asuka Langley Soryu | |

|---|---|

| Neon Genesis Evangelion character | |

Asuka with her Eva-02 (in the background) as a child (left), as a pilot (center) and in civilian clothes (right) | |

| First appearance | Neon Genesis Evangelion episode 8: "Asuka Strikes!" (1995) |

| Created by | Gainax |

| Voiced by | Japanese: Yūko Miyamura English: Tiffany Grant (ADV Films dub, Rebuild) Stephanie McKeon (Netflix dub) |

| In-universe information | |

| Alias | Asuka Shikinami Langley (Rebuild) |

| Species | Human |

| Gender | Female |

| Title | Second Child Captain (Rebuild) |

| Relatives | Kyoko Zeppelin Soryu (mother) Ryoji Kaji (guardian) Misato Katsuragi (guardian) |

| Nationality | German-American |

Hideaki Anno, director of the animated series, originally conceived her as main protagonist of the series. Character designer Yoshiyuki Sadamoto asked the director to include a male main character instead, downgrading her to the role of co-protagonist with Shinji Ikari. Anno based her psychology on his own personality, bringing his moods into the character, acting instinctively and without having thought about how the character would evolve. During the first broadcast of the series he changed his plans, creating an evolutionary parable in which the character becomes more dramatic and suffering, intentionally going against the expectations of the fans. Japanese voice actress Miyamura was also influential, deciding some details and lines of Asuka.

Asuka maintained a high ranking in every popularity poll of the series and has also appeared in polls to decide the most popular anime characters in Japan. Merchandising based on her has also been released, particularly action figures, which became highly popular. Some critics blamed her hubris and her personality, judged as tiresome and arrogant; others appreciated its realism and complex psychological introspection. Asuka is also considered one of the most successful and influential examples of the tsundere stereotype, helping to define its characteristics.

Conception

In the early design stages of Neon Genesis Evangelion, director Hideaki Anno proposed to include a girl similar to Asuka as the protagonist of the anime.[2] Character designer Yoshiyuki Sadamoto proved reluctant to the idea of re-proposing a female character in the lead role after the previous works of Gainax, such as Gunbuster and Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water; he himself declared: "A robot should be piloted by a trained person, whether it is a woman or not makes no difference, but I cannot understand why a girl should pilot a robot." Sadamoto asked the director to include a boy in the role of main character, thus downgrading her to the role of female co-protagonist. Sadamoto himself modeled the relationship between Asuka and male protagonist Shinji Ikari basing on Nadia and Jean from The Secret of Blue Water. Asuka should have represented "[Shinji's] desire for the female sex", as opposed to Rei Ayanami's "motherhood",[3] and should have been "the idol of Neon Genesis Evangelion".[4] In the initial project she was described as "a determined girl" who tends to adapt to the situation, passionate about video games and who "aspires to become like Ryoji Kaji".[5] In the nineteenth episode, moreover, she would have had to be seriously injured in an attempt to protect Shinji, who would have thus "proved his worth" in an attempt to save her.[6]

For the name of the character Hideaki Anno took inspiration from Asuka Saki (砂姫 明日香, Saki Asuka), protagonist of the manga Super Girl Asuka (超少女明日香, Chō Shōjo Asuka), written by Shinji Wada; for the surname, on the other hand, he merged the names of two ships used in the Second World War, the Japanese World War II aircraft carrier Soryu and the American aircraft carrier Langley.[7][8] Despite her multiethnic origins, however, the production decided to make Asuka's skin the same color as Rei Ayanami, another character with Japanese nationality.[9] To better outline the girl's psychology the director relied on his own personality, making his moods converge in her character.[10][11]

For the German terms used in the scenes with Asuka, Anno asked help to the American member of Gainax, Michael House, who exploited his basic knowledge of the language, acquired in high school, and a Japanese-German dictionary from a local library.[12] Gainax did not pay attention to the German grammar of the dialogues, believing that the series could never be successful enough to be distributed to native speakers.[13] Anno originally inserted Asuka with the aim of lightening the atmosphere of the series, without foreseeing any particular evolutionary parable of the character. To define her role and outline her psychology, moreover, he chose some recurring lines like "Are you stupid?" or "Chance!" and preferred to act instinctively, without following a plan.[14] During the first airing of the series, moroever, the director began to criticize otaku, Japanese obsessed animation fans, accusing them of being excessively closed and introverted; therefore he changed the atmosphere of the second half of the series, making the plot darker, violent and introspective. The change also reflected on Asuka's story: although she had been introduced in an essentially positive role, the character became increasingly dramatic and introverted, going against the expectations and the pleasure principle of anime fans.[15][16] In the twenty-second episode he decided to focus on the disastrous emotional situation of the girl, harassed by her first menstrual cycle, but, not considering herself capable of exploring such a delicate and feminine theme, he decided to condense everything into a single scene.[17] Also the interpretation of Miyamura and the lack of time that affected the realization of the last two episodes were decisive. During production he therefore decided to insert scenes in which he represented Asuka with simple hand-drawn sketches, remaining extremely satisfied with the result and characterization of the character.[18] he original intent of the authors was a long live action segment for the film, with a different content than the final version.[19] The original segment focused on the character of Asuka, who would wake up in an apartment after drinking and spend the night with Tōji Suzuhara, with whom she would embark on a sexual and sentimental relationship. Misato Katsuragi would have been the roommate of the apartment next to her; Rei Ayanami she would have been a colleague and a senpai for her. In the alternate universe of live action Shinji would never have existed; walking the streets of Tokyo-2, however, Asuka would hear his voice calling her.[20][21]

Voice

Asuka's character is voiced by the seiyū Yūko Miyamura in all her appearances in the original series, as well as the later films, spin-offs, video games[23][24] and the new Rebuild of Evangelion film series. The only exception is an introspective scene from the twenty-second episode, in which she was voiced by the other female members of the original cast, such as Kotono Mitsuishi, Megumi Hayashibara, Miki Nagasawa, Yuriko Yamaguchi and Junko Iwao.[25] According to Miyamura, Asuka's dubbing proved to be difficult. She also declared to have wished to "erase Evangelion" and forget her experience with it.[26] Towards the end of the first broadcast, in fact, the seiyū suffered from bulimia and found herself in a disastrous psychic state, similar to that of Asuka's character.[27] Despite the numerous problems that her work was causing her, however, she tried to fulfill her task, remaining until the end.[28] The voice actress, despite the difficulties, identified herself so much to follow a conversation course in German, decide some lines of the girl and define some details, such as the cloth puppet in the shape of a monkey featured in her childhood flashbacks.[29][30] One of her ideas, for example, were the German sentences that Asuka utters in the twenty-second episode of the series in a telephone conversation with her stepmother.[31]

When dubbing the last scene of The End of Evangelion (1997), in which Shinji Ikari strangles Asuka, Shinji's voice actress Megumi Ogata physically imitated his gesture and strangled her colleague. Because of her agitation, she squeezed her neck too hard, risking not to make her properly recite the other lines of the film.[32] With Ogata's gesture Miyamura was finally able to produce realistic sounds of a strangulation, thanking her colleague for her availability.[33] Anno based the scene on a fact that actually happened to one of his female friends. His friend was strangled by a malicious man, but, when she was about to be killed, she stroked him for no reason. When the man stopped squeezing her neck, the woman regained a cold attitude,[34] speaking the words that Asuka would have said to Shinji in the original script: "I can't stand the idea of being killed by someone like you" (あんたなんかに殺されるのは真っ平よ).[35][36] Dissatisfied with Miyamura's interpretation, Anno asked her to imagine a stranger sneaking into her room, who could rape her at any time but who prefers to masturbate by watching her sleep. The director also asked her what she would say about her if she woke up suddenly, noticing what had happened. Miyamura, disgusted by the scene, replied by saying "Kimochi warui" (気持ち 悪い, "How disgusting" or "I feel sick"). After the conversation, Anno changed the line by echoing the voice actress's reaction.[37] Further difficulties arose during the dubbing sessions for the film Evangelion: 3.0 You Can (Not) Redo (2012), third installment of the Rebuild saga, set fourteen years after the previous movies. According to Miyamura herself, the scenario made her feel "very confused feelings" and "a constant feeling of lightheadedness." Hideaki Anno himself did not explain the plot and setting of the film to her, complicating her work.[38]

In English, Asuka is voiced by Tiffany Grant in the ADV Films dub and by Stephanie McKeon in the Netflix dub.[39] Grant felt that playing Asuka was "refreshing", as "she says the most horrible things to people, things that you'd like to say to people and can't get away with".[40]

Appearances

Neon Genesis Evangelion

Asuka Langley Sōryū was born on December 4, 2001.[41] She is the daughter of Dr. Sōryū Kyōko Zeppelin, an employee of a research center named Gehirn. She has German and Japanese blood and US citizenship.[42] In 2005, her mother participated in a contact experiment with Unit 02, but, due to an accident, suffered a severe mental breakdown, becoming permanently hospitalized. The mental injuries incurred during the failed experiment also render her unable to recognize her own child. Asuka is deeply hurt by her mother's behavior, who speaks to a doll believing it to be her daughter. After some time, Asuka is chosen as the Second Child and Eva-02's official pilot.[43][44] Hoping that her selection could cause her mother to pay attention to her again, she excitedly runs to her room to announce the news, only to find her corpse hanging from the ceiling.[45] Shocked and traumatized by her mother's suicide, Asuka adopts her self-affirmation as the only reason to be, participating in training sessions in order to become a pilot and meet other people's expectations.[46]

At the age of fourteen, after graduating from her German university, Asuka leaves Germany, accompanied by her guardian Ryoji Kaji and Unit 02, on board a United Nations aircraft carrier escorted by numerous warships there to protect the Eva. During the trip, she meets Shinji Ikari, Third Child and pilot of Unit 01, and her new classmates Tōji and Kensuke. The United Nations fleet is then attacked by Gaghiel, the sixth Angel.[47] Recognizing this event as a good chance to demonstrate her skills, Asuka independently decides to activate her Eva, coercing Shinji into joining her in the cockpit.[48] Despite struggling to work together and the Eva not yet being equipped to operate underwater, the two Children manage to destroy the enemy. She is later placed in class 2-A of Tokyo-3 first municipal middle school.[49], living with Shinji under Misato Katsuragi's care.[50][51] She continuously teases Shinji about his passivity and perceived lack of manliness, but gradually comes to respect and like him as they fight Angels together, though she is rarely able to express these feelings. However, following a series of Angel battles in which Shinji outperforms her, she increasingly grows unable to continue to suppress her traumatized psyche, drastically lowering her pilot skills in the process.[52][53] This comes to a head when the Angel Arael attacks; Asuka, burdened by her continually worsening performance in tests, is infuriated by being ordered to serve as backup to Rei. She defies this order and tries to attack the Angel alone, but is overwhelmed by the Angel's attack, a beam that penetrates her mental barrier and forces her to relive her darkest memories.[54] In the battle with the next Angel, Armisael, she becames unable to activate the Evangelion.[55] As a result of this, Asuka loses all will to live, goes to the home of her classmate Hikari Horaki[56][57] and then spends time aimlessly roaming the streets of Tokyo-3. She is eventually found by Nerv personnel, naked and starving herself in the bathtub of a ruined building. The main series ends with her lying in a hospital bed in a catatonic state.[58][59]

The End of Evangelion

In the movie The End of Evangelion (1997), as the Japanese Strategic Self-Defense Force invade Nerv headquarters, Asuka is placed inside Unit 02, which is then submerged in a lake for her own protection. As she is bombarded by depth charges, Asuka wakes up, declares that she does not want to die, and, in a moment of clarity, realizes that her mother's soul is within the Eva and has been protecting her all along. Her self-identity regained, she emerges and defeats the JSSDF, before encountering nine mechas named Mass-Production Evas.[60] Though she successfully disables all nine opponents, Eva-02's power runs out; the near infinite power of the mass-produced Evas allow them to eviscerate and dismember Unit 02.[61] Seeing Asuka's destroyed Evangelion makes Shinji go into a frenzy, which eventually culminates in him starting a catastrophic event named Third Impact. Shinji and Asuka have an extended dream-like sequence inside Instrumentality, a process in which the soul of the entire humanity merge in one collective consciousness; Asuka claims she can't stand the sight of him, but Shinji responds that it is because he is just like her. Shinji claims he wants to understand her, but she refuses. He is furious at this rejection, and lashes out by choking her. After Shinji rejects Instrumentality, she returns some time after him in the new world; in the film's final scene, Shinji begins to strangle Asuka, but stops when she caresses his face.[62]

Rebuild of Evangelion

In the Rebuild of Evangelion saga, Asuka makes her first appearance in the second film, Evangelion: 2.0 You Can (Not) Advance (2009). Changes have been made to her character, such as her family name being changed from Sōryū (惣流) to Shikinami (式波),[63][64] continuing the Japanese maritime vessel naming convention. The name change was the result of a precise choice by Hideaki Anno, who said he had somehow changed the background of the character.[65] Asuka Shikinami Langley, compared to her original counterpart, seems even more open and vulnerable: in one of the scenes of the film, for example, she confides in someone for the first time talking genuinely about her feelings with Misato,[66] she does not feel any infatuation with Ryōji Kaji and maintains a more affectionate and peaceful relationship with Shinji.[67] At the beginning of the film, the young woman strongly refuses any kind of contact with other people and Shinji, only to feel strong jealousy towards her and a certain interest in his feelings.[68][69] During the production phase, to better illustrate the evolutionary parable of the character, the screenwriter Yōji Enokido has added a night scene in which the girl, feeling alone, enters without permission in her partner's room, sleeping with him.[70] In the course of events she also plays video games and tries to cook something for Shinji.[71] She also has the role of captain at Nerv, faces the seventh Angel with her Eva-02 and is designated pilot of the Eva-03, whereas in the original series her role was Tōji Suzuhara.[72] Unit 03 is later contaminated by a parasitic-type Angel, Bardiel, and collides with Eva-01; Asuka eventually survives to the fight, but is last seen in urgent care.[73]

In Evangelion: 3.0 You Can (Not) Redo (2012), third installment of the saga, Asuka is initially part of the rescue operation for Eva-01, which is stranded in space, and is now working together with Mari supporting her piloting Eva-08 for an organization named Wille, born in order to destroy Nerv. After fighting off an initial attack by Nerv, Asuka confronts Shinji in his holding cell and tells him fourteen years have passed. Asuka is biologically twentyeight years old, but hasn't physically aged thanks to what she calls "the curse of the Evas", and she's wearing an eyepatch which glows blue. Asuka, again supported by Mari, confronts Shinji and his fellow pilot Kaworu Nagisa and eventually self-destructs her Eva during the fight. After the fight she grabs Shinji's wrist and they start moving along the ruins of Tokyo-3, followed by Rei Ayanami.[74]

In other media

In a scene from the last episode of the animated series an alternate universe is presented with a completely different story than in the previous installments, in which Asuka is a normal middle school student and a childhood friend of Shinji Ikari. In the alternate reality of the episode the Evangelion units never existed, which is why Asuka did not experience any childhood trauma due to her mother Kyōko.[75] A similar version of events can be found in Neon Genesis Evangelion: Shinji Ikari Raising Project,[76] Neon Genesis Evangelion: Angelic Days[77] and the parodistic series Petit Eva: Evangelion@School,[78][79] in which she behaves towards Shinji like a sister.[80] In Neon Genesis Evangelion: Girlfriend of Steel 2nd Asuka openly comes into conflict with Rei Ayanami to contend for Shinji's romantic attentions.[81]

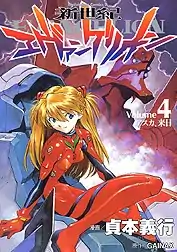

In the Neon Genesis Evangelion manga, illustrated and written by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, Asuka has a more immature character than her animated counterpart and her story is different; despite having a similar familiar past, in the manga she was conceived through artificial fertilization, as the result of an experiment in eugenics.[82] In her first actual battle against Gaghiel, whom she confronts alongside Shinji in the same Evangelion unit in the classic series, she fights alone, while Shinji later watches the fight recorded on a projector.[83] In addition, in the comic her fellow pilot Kaworu Nagisa is introduced before and interacts with her, immediately arousing her antipathy.[84] Further differences are presented in the last chapters of the manga, corresponding to the events of the movie The End of Evangelion. In the feature film the Eva-02 is dismembered by the Eva Series before Shinji's arrival, while in the comic the Third Child manages to intervene in battle in her defense.[85] In the final chapter of the comic, following the failure of Instrumentality, Shinji lives in a world where it snows again in Japan and where people don't seem to have any memory of recent events. The Third Child, traveling on a train to his new school, meets a girl similar to Asuka.[86] According to Sadamoto, the girl is not concretely Asuka, but the symbol "of an attractive woman that Shinji can meet in the new world".[87]

Asuka is older and more mature in Evangelion Anima, having developed a strong friendship with Shinji and even Rei. She also appears in the crossover Transformers x Evangelion, in the videogames based on the original animated series and medias not related to the Evangelion franchise, including Monster Strike,[88] Super Robot Wars,[89] Tales of Zestiria,[90] Puzzle & Dragons,[91] Keri hime sweets, Summons Board,[92][93] Puyopuyo!! Quest[94] and in an official Shinkansen Henkei Robo Shinkalion cross-over episode.[95] In the Super Robot Wars franchise she butts heads with Kouji Kabuto, the pilot of Mazinger Z and Mazinkaiser. She is also implied to have developed crushes on famous heroes such as Char Aznable (in the guise of Quattro Bageena) and Amuro Ray, but proves jealous of Shinji, who crushes for Lynn Minmay from the Macross franchise.[96]

Characterization and themes

| At first glance obviously she comes across rather brash and pushy and loud, and I understand that, but the more you get to know her the more you come across her motivations behind this, and you always have to keep in mind that she's still only fourteen, so no matter how terribly educated or clever she might be she's only a fourteen-year-old girl. So I think in the end her heart is in the right place but she has a hard time communicating that with her emotions and everything, how she really feels. I mean, she wants to have friends and she wants to be liked. |

| –Tiffany Grant[97] |

Asuka is an energetic,[98] proud[99][100] and enterprising[101] girl with a resolute character.[102] She tends to look down on other people[103] and wants to constantly be at the center of attention.[104][105] Although she normally shows a stubborn and exuberant attitude, in some moments she exhibits a kinder, more sensitive and caring side.[106] Her abrupt and impulsive ways often arouse other people antipathy, since they do not fully understand her real intentions.[107][108] Unlike fellow pilots Shinji and Rei, she is extremely proud of her pilot role and engages with great enthusiasm in missions,[109] but despite her apparently strong, aggressive and competitive character, Asuka suffers from the same sense of alienation as her companions.[110] Asuka suffers from masculine protest,[111] a psychologic expression to indicate exaggeratedly masculine tendencies in tired and rebellious women who protests against traditional female gender role. She sees her male peers merely as rivals and spectators of her abilities,[112] and suffers from a marked emotional complex for male sex, merging a so-called "radical rivalry" and a latent inferiority complex. Her masculine protest is reflected in her strong misandric tendencies, since she's dominated by the need to beat male peers with an obsessive self-affirmation desire. This leads her to continuously attack Shinji's virility,[113][114] directing both interest and open hostility at him.[115][116] Due to their intimate fragility and insecurities, Shinji and Asuka are unable to effectively communicate with one another on an emotional level, despite their mutual latent interest.[117][118]

Asuka's excessive pride prevents her from admitting—even to herself—that she feels something for Shinji,[119][120] and as events and battles progress her feelings of love and hate intensify and dominate her.[121][122] She kisses Shinji in the fifteenth episode,[123] but when he beats her in pilot tests she begins to develop a profound inferiority complex towards him.[124] Despite her deep distrust toward most men, she has a deep sense of admiration for her guardian and senpai, Ryōji Kaji.[125] Asuka is emotionally dependent on Kaji, since she has a strong subconscious desire to find a reference figure to rely on.[126] Asuka's infatuation also leads her to feel great jealousy for him and she eventually tries to seduce him.[127][128] Asuka's relationship with Rei Ayanami is equally tormented. She despises Rei by calling her "Miss Perfect" (優等生, yūtōsei) and "mechanical puppet girl".[129][130] In a scene from the 22nd episode Rei confesses to be ready to die for commander Gendō Ikari, provoking Asuka's anger, who slaps her and confesses to having hated her from the first moment they met.[131] Shortly thereafter, Rei helps her during the fight against Arael, an act that destroys her already wounded pride.[132]

Her ostentatious competitiveness originates from her childhood experience, marked by the mental illness and consequent suicide of her mother Kyōko.[133][134] Asuka faced her loss by immersing herself in pride, becoming indisposed to any kind of help or advice and adopting strength and self-affirmation as her only raison d'être.[135][136] Tormented "by the fear of not being necessary",[137] she pilots Unit-02 only to satisfy her intimate desire for acceptance, longing to be considered "an élite pilot who will protect humanity".[138] Her excessive self-confidence leads her to clash with Shinji,[139][140] gradually losing self-confidence[141][142] and becoming psychologically and physically compromised.[143][144] The Fourth Child's selection, Tōji Suzuhara, also contributes to the destruction of her pride.[145][146] After she learns of Kaji's death[147] she questions the meaning of her life and her identity,[148] avoiding any kind of human contact and never meeting the gaze of other people.[149] Overwhelmed by the fear of being alone,[150][151] the young woman shows that she has a great and morbid need for the Eva, even more than her colleague Shinji has. In a scene from the twenty-fifth episode she excoriates the machine as a "worthless piece of junk", but then immediately goes on to admit that "I'm the junk".[152] Her self-love represents an act of psychological compensation in order to be recognized in the eyes of other people. After her mother's mental illness she represses her sadness and eventually decides to not cry anymore and behave like an adult with a reaction formation.[153] Her memories related to her past and her mother are repressed and removed from her consciousness during this phase.[154] In the last episodes, Asuka completely loses her self-confidence. She also develops a deep disgust toward herself and suffers from separation anxiety.[155][156]

Cultural impact

Popularity and critical reception

| If you're an anime fan, you've definitely heard of Asuka, even if you haven't watched Evangelion. She's ranked high in popularity polls for a reason, and it's easy to see why. As one of the more dynamic characters in the show, she commands every scene that she's in ... I first saw this series as a teenager myself, and seeing Asuka at her highs and her lows felt extremely validating. There's a lot of truth to be told in the problems that she has .... The story never forces her to become a cleaner version of herself, but lets her have struggles in a way that not many series would allow. She isn't perfect, far from it, and there's a lot of strength to be found in that. |

| –Noelle Ogawa (Crunchyroll)[157] |

Website Otaku Kart described Asuka as "one of the most popular female characters in anime history".[158] She emerged in various polls on best anime pilots[159][160] and female anime characters,[161][162][163] proving popular among both female and male audience.[164][165] In 1996 she ranked third among the "most popular female characters of the moment" in the Anime Grand Prix survey by Animage mangazine, behind Rei Ayanami and Hikaru Shido from Magic Knight Rayearth.[166] In 1997 and 1998 Anime Grand Prixes she also managed to remain among the top 10 female characters; in 1997 she ranked in fourth place, while in 1998 she ranked sixth.[167][168] Asuka also appeared in the monthly surveys of the magazine, remeaning in the top 20 in 1996,[169] 1997[170][171][172] and 1998 polls.[173][174][175] In 1999 Animage ranked her 40th among the 100 most popular anime characters.[176] Her popularity increased after the release of the second Rebuild of Evangelion movie; in August and September 2009 she emerged in first place and remained the most popular female Neon Genesis Evangelion character in Newtype magazine popularity charts,[177][178] while in October she ranked tenth.[179] In a Newtype poll from March 2010 she was voted as the third most popular female anime character from the 1990s, immediately after Rei Ayanami and Usagi Tsukino from Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon.[180] In February 2015, almost twenty years after the show first aired, she again emerged on the magazine's charts in sixth place.[181] In 2017 she also ranked 16th among the characters Anime Anime readers would "rather die than marry" with.[182] Her line "Are you stupid?" (あんたバカ?, Anta baka?) also became widely used among hardcore fans since her first appearance in eight episode.[183]

Asuka divided anime critics, receiving an ambivalent response. Negative reviews criticized her arrogant, surly and authoritarian character.[184][185] While appreciating her for providing "a good dose of comic relief" to Evangelion, Anime Critic Pete Harcoff described her as "an annoying snot".[186] Raphael See from T.H.E.M. Anime Reviews, who found Neon Genesis Evangelion characterization "a little cliché, or just plain irritating at times", despised Asuka for her arrogant attitude.[187] Anime News Network editor Lynzee Loveridge ranked her seventh among the "worst sore losers" of anime history.[188] IGN critic Ramsey Isler ranked her as the 13th greatest anime character of all time for the realism of her characterization, saying: "She's a tragic character, and a complete train wreck, but that is what makes her so compelling because we just can't help but watch this beautiful disaster unfold".[189] CBR included her among the best anime female pilots,[190] describing her as "the best classic tsundere in shounen anime" and "one of the most fascinating characters in anime".[191][192]

Screen Rant ranked her among the best Neon Genesis Evangelion characters, praising her development.[193][194] WatchMojo listed her second among the best mecha pilots in Japanese animation.[195] According to critic Jay Telotte, Asuka is "the first credible multinational character" in the history of Japanese science fiction television.[196] Crunchyroll and Charapedia also praised her realism and personality.[157][197] Asuka's fight sequence against the Mass-Production Evangelions in The End of Evangelion was particularly well received by critics.[198][199] Praise was also given to Tiffany Grant for her role as Asuka's English voice actress. Mike Crandol of Anime News Network stated that Grant was "her fiery old self as Asuka."[200] Eric Surrell (Animation Insider) also commented on Asuka's role in Evangelion: 2.0 You Can (Not) Advance (2009), second installment of the Rebuild saga, stating that "the arrival and sudden dismissal of Asuka was shocking and depressing, especially considering how integral she was to the original Evangelion."[201] Slant Magazine's Simon Abrams, reviewing Evangelion: 2.0, negatively saw new Shinji and Asuka's relationship, "which is unfortunate because that bond should have the opportunity to grow in its own time".[202]

Legacy

Asuka's character has been used for merchandising items, such as life-size figures,[203] different action figures,[204][205] guitars,[206] clothes[207][208] and underwear, some of which immediately sold out.[209][210] Her action figures also proved successful, contributing significantly to the revenue of the Neon Genesis Evangelion franchise.[211] According to Japanese writer Kazuhisa Fujie, Asuka's figures have become so popular that they have run out of stock and have been put back on the market with a second edition.[212] On February 27, 1997 Kadokawa Shoten published a book dedicated to her, entitled Asuka - Evangelion Photograph (ASUKA-アスカ- 新世紀エヴァンゲリオン文庫写真集).[213] In 2008 Broccoli released a videogame entitled Shin Seiki Evangelion: Ayanami Ikusei Keikaku with Asuka Hokan Keikaku, in which the player takes on the task of looking after Asuka and Rei Ayanami.[214]

Japanese celebrities cosplayed her during concerts or tours, including Saki Inagaki,[215][216] Haruka Shimazaki[217] and singer Hirona Murata.[218] In 2019 Lai Pin-yu, a Taiwanese Democratic Progressive Party and Legislative Yuan member, held election rallies cosplaying Asuka, gaining great popularity.[219] Asuka's character was mentioned and parodied by Excel from Excel Saga[196] and some of her aesthetic and character traits inspired other female characters. Anthony Gramuglia (Comic Book Resources) identified her as one of the most popular and influential examples of the tsundere stereotype, a term used to indicate grumpy, assertive and authoritarian characters, often characterized by a more gentle, empathetic and insecure side, hidden due to stormy past or traumatic experiences. Gramuglia compared Asuna Yūki (Sword Art Online), Rin Tōsaka (Fate/stay night), Kyō Sōma (Fruits Basket) and Taiga Aisaka (Toradora!) to her.[220][221] Critic also compared Mai Shibamura from Gunparade March,[222] Michiru Kinushima from Plastic Memories[223] and D.Va from Overwatch game series to Asuka.[224] Japanese band L'Arc-en-Ciel also took inspiration from Asuka for the song "Anata".[225]

References

- Her surname is romanized as Soryu in the English manga and Sohryu in the English version of the TV series, the English version of the film, and on Gainax's website.

- Takekuma Kentaro, ed. (March 1997). 庵野秀明パラノ・エヴァンゲリオン (in Japanese). Ōta Shuppan. pp. 134–135. ISBN 4-87233-316-0.

- "貞本義行インタビュー". Newtype (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten: 26–29. December 1997.

- "Interview with Sadamoto Yoshiyuki". Der Mond: The Art of Yoshiyuki Sadamoto - Deluxe Edition. Kadokawa Shoten. 1999. ISBN 4-04-853031-3.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 15. Sony Magazines. p. 27.

- Gainax (February 1998). Neon Genesis Evangelion Newtype 100% Collection (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. pp. 87–88. ISBN 4-04-852700-2.

- Fujie, Kazuhisa; Foster, Martin (2004). Neon Genesis Evangelion: The Unofficial Guide. United States: DH Publishing, Inc. p. 120. ISBN 0-9745961-4-0.

- Anno, Hideaki (November 2, 2000). "Essay" (in Japanese). Gainax. Archived from the original on February 20, 2007. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 7. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 67.

- "鶴巻 和哉 interview". ヱヴァンゲリヲン新劇場版:破 全記録全集 (in Japanese). Ground Works. 2012. pp. 323–351. ISBN 978-4-905033-00-4.

- "EVA SPECIAL TALK with 庵野秀明+上野俊哉". Newtype (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. November 1997.

- "Interviewing translator Michael House". Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- Callum May (March 2, 2018). "The Indestructible Studio Gainax: Part III". Anime News Network. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- "あんた、バカぁと、言われてみたい。(庵野秀明、宮村優子)". Animage (in Japanese). Tokuma Shoten. July 1996.

- Woznicki, Krystian (1997). "Towards a cartography of Japanese anime: Hideaki Anno's "Evangelion"". Blimp Film Magazine (36): 18–26. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- "新世紀エヴァンゲリオン』をめぐって(庵野秀明×東浩紀)". Studio Voice (in Japanese). INFAS. October 1996.

- "庵野秀明 - Part I". Zankoku na tenshi no you ni. Magazine Magazine. 1997. ISBN 4-906011-25-X.

- "EVA, 再擧 庵野秀明 スペシャルインタビュー ニュータイプ". Newtype (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten: 10–15. June 1996.

- "第62回 エヴァ雑記「第26話 まごころを、君に」" (in Japanese). Archived from the original on January 2, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- Renewal of Evangelion Extras (in Japanese). King Amusement Creative. 2003.

- Gainax, ed. (2003). Data of Evangelion (in Japanese). pp. 84–89.

- Yūko Miyamura (2013). "A Place For Asuka in the Heart". Neon Genesis Evangelion 3-in-1 Edition. 2. Viz Media. pp. 182–183. ISBN 978-1-4215-5305-4.

- "鋼鉄のガールフレンド 2nd - Report". Gainax.co.jp (in Japanese). Gainax. Archived from the original on October 9, 2007. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- "惣流・アスカ・ラングレー役の声優 宮村優子さんへのアフレコインタビュー!". Broccoli.co.jp (in Japanese). BROCCOLI. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Platinum Edition Booklets. 6. A.D. Vision. 2005.

- "Interview with Yūko Miyamura - SMASH 2010". Anime News Network. April 5, 2011. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- "Two Big Anime Movies this Summer!". Nikkei Entertainment (in Japanese). August 1997.

- "声ノ出演". The End of Evangelion Theatralical Pamphlet (in Japanese). Gainax. July 19, 1997.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 8. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 52.

- "CASTから一声". EVA友の会 (in Japanese). 4. 1997.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 8. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 43.

- "Rocking the Boat". Akadot. April 27, 2001. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- "Gold Coast Film Festival - Yuko Miyamura Interview". Rave Magazine. November 9, 2012. Archived from the original on November 19, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- "VOICE OF EVANGELION". 井手功二のエヴァンゲリオンフォーエヴァー (in Japanese). Amuse Books. September 1997. ISBN 4-906613-24-1.

- 新世紀エヴァンゲリオン 劇場版 絵コンテ集 (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. 1998. p. 841. ISBN 4-04-904290-8.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion: The Feature Film - DTS Collector's Edition Booklet (in Italian). Dynit. 2009. p. 15.

- BSアニメ夜話 (in Japanese). Nippon Hōsō Kyōkai. March 28, 2005.

- ヱヴァンゲリヲン新劇場版:Q 記録集 (in Japanese). November 17, 2012. pp. 53–54.

- Patches, Matt (June 21, 2019). "Netflix's Neon Genesis Evangelion debuts English re-dub".

- "Otakon Highlights - Evangelion Voice Actors - Aug. 7, 1998". Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 1. Sony Magazines. p. 16.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 14. Sony Magazines. p. 23.

- Gainax, ed. (1997). "Death & Rebirth Program Book" (in Japanese): 40. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Poggio, Alessandra (2008). Neon Genesis Evangelion Encyclopedia (in Italian). Dynit. p. 76.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 2. Sony Magazines. p. 14.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 9. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 40.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 10. Sony Magazines. p. 14.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side A (in French). Glénat. 2009. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-2-7234-7120-6.

- Gualtiero Cannarsi. Evangelion Encyclopedia (in Italian). 4. Dynamic Italia. pp. 33–34.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 11. Sony Magazines. p. 15.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side A (in French). Glénat. 2009. p. 85. ISBN 978-2-7234-7120-6.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 25. Sony Magazines. p. 13.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 8. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 41.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 25. Sony Magazines. p. 15-16.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 1. Sony Magazines. p. 24-25.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side B (in French). Glénat. 2010. p. 74. ISBN 978-2-7234-7121-3.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 26. Sony Magazines. p. 13.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side B (in French). Glénat. 2010. p. 78. ISBN 978-2-7234-7121-3.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 27. Sony Magazines. p. 15.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side B (in French). Glénat. 2010. p. 88. ISBN 978-2-7234-7121-3.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side B (in French). Glénat. 2010. p. 94. ISBN 978-2-7234-7121-3.

- Hideaki Anno, Kazuya Tsurumaki, Masayuki (directors) (1997). Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion (Film). Studio Gainax.

- 「ヱヴァンゲリヲン新劇場版:破」作品情報 -キャラクター紹介- (in Japanese). Archived from the original on February 16, 2010. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- Sombillo, Mark (June 7, 2011). "Evangelion: 2.22 - You Can (Not) Advance - DVD". Anime News Network. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- "庵野 秀明 interview". ヱヴァンゲリヲン新劇場版:破 全記録全集 (in Japanese). Ground Works. 2012. ISBN 978-4-905033-00-4.

- Theron, Martin (March 31, 2011). "Evangelion 2.22: You Can (Not) Advance". Anime News Network. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- "今夜金曜ロードSHOW「ヱヴァンゲリヲン:破」惣流と式波アスカの違いを検証" (in Japanese). August 29, 2014. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- "お貞本2009, Osada bon". Young Ace (in Japanese). No. 3. Kadokawa Shoten. October 2009.

- Ekens, Gabriella (February 19, 2016). "The Evolution of Evangelion: Rebuild vs. TV". Anime News Network. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- "榎戸 洋司interview". ヱヴァンゲリヲン新劇場版:破 全記録全集 (in Japanese). Ground Works. 2012. pp. 232–238. ISBN 978-4-905033-00-4.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 34. Sony Magazines. pp. 3–4.

- Sevakis, Justin (November 24, 2009). "Evangelion: 2.0 You Can [Not] Advance". Anime News Newtork. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- Hideaki Anno, Kazuya Tsurumaki, Masayuki (directors) (2009). Evangelion: 2.0 You Can (Not) Advance (Film). Studio Khara.

- Hideaki Anno, Kazuya Tsurumaki, Masayuki (directors) (2013). Evangelion: 3.0 You Can (Not) Redo (Film). Studio Khara.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 22. Sony Magazines. p. 8.

- "新世紀エヴァンゲリオン 碇シンジ育成計画 (1)" (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- "Neon-Genesis Evangelion The Iron Maiden 2nd T1" (in French). Planet BD. January 1, 2008. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- "ぷちえヴぁ" (in Japanese). Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- "Petite Eva?!". Newtype USA. June 2007. p. 67.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 33. Sony Magazines. p. 20.

- "鋼鉄のガールフレンド 2nd" (in Japanese). Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- "Stage 24: Dissonance". Neon Genesis Evangelion. 4. Viz Media. June 9, 2004. ISBN 978-1-59116-402-9.

- "Stage 20: Asuka Comes to Japan". Neon Genesis Evangelion. 4. Viz Media. June 9, 2004. ISBN 978-1-59116-402-9.

- Gramuglia, Anthony (April 29, 2020). "The Best Version of Evangelion's Story Isn't Animated". CBR. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2013.

- "Stage 84: Calling". Neon Genesis Evangelion. 13. Viz Media. November 2, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4215-5291-0.

- "Final Stage: Setting Off". Neon Genesis Evangelion. 14. Viz Media. November 25, 2014. ISBN 978-1-4215-7835-4.

- "貞本 義行". CUT (in Japanese). Rockin'On. December 2014. pp. 54–59.

- "【モンスト】「エヴァンゲリオン」コラボ第3弾が開催!限定ガチャや「葛城ミサト」も新登場" (in Japanese). October 5, 2017. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- "Import Review: Super Robot Wars V". April 26, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ""Evangelion" Costume Set for "Tales of Zestiria" Offered in America and Europe". November 12, 2015. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- "Neon Genesis Evangelion Revisits Puzzle & Dragons". November 17, 2015. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- "『ケリ姫スイーツ』と『エヴァンゲリオン』コラボが復活!「第13号機 疑似シン化」などの新キャラクターが登場" (in Japanese). November 25, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- "『サモンズボード』に使徒、再び!『エヴァンゲリオン』コラボ情報まとめ" (in Japanese). October 19, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- "セガゲームス、『ぷよぷよ!!クエスト』で「エヴァンゲリオン」コラボを開始! 「葛城ミサト」役・三石琴乃さんナレーションのテレビCMも放映中" (in Japanese). August 10, 2018. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- "Rei, Asuka VAs Confirmed, Angel-Themed Villain Revealed for Shinkalion's Giant Eva Episode". August 9, 2018. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- B.B. Studio (2000). Super Robot Wars Alpha (PlayStation) (in Japanese). Banpresto.

- "Interview with Tiffany Grant". Anime News Network. March 31, 2011. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 3. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 4.

- Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, Khara/Gainax (2012). "Cast". Evangelion (in Italian). 25. Panini Comics. p. 3.

- "Evangelion - Characters" (in Japanese). Archived from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 4. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 4.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 5. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 4.

- Fujie, Kazuhisa; Foster, Martin (2004). Neon Genesis Evangelion: The Unofficial Guide. United States: DH Publishing, Inc. p. 40. ISBN 0-9745961-4-0.

- Poggio 2008, p. 23.

- Platinum Booklet. 2. ADV. 2004.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 7. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 4.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 6. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 4.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 9. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 4.

- Fujie, Kazuhisa; Foster, Martin (2004). Neon Genesis Evangelion: The Unofficial Guide. United States: DH Publishing, Inc. pp. 83–84. ISBN 0-9745961-4-0.

- Ishikawa, Satomi (2007). Seeking the Self: Individualism and Popular Culture in Japan. Peter Lang. p. 75. ISBN 978-3-03910-874-9.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side B (in French). Glénat. 2010. p. 73. ISBN 978-2-7234-7121-3.

- "第41回 エヴァ雑記「第八話 アスカ、来日」" (in Japanese). Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Gualtiero Cannarsi. Evangelion Encyclopedia (in Italian). 6. Dynamic Italia. pp. 44–45.

- Gualtiero Cannarsi. Evangelion Encyclopedia (in Italian). 5. Dynamic Italia. pp. 24–25.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 3. Sony Magazines. p. 8.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side A (in French). Glénat. 2009. p. 6. ISBN 978-2-7234-7120-6.

- "What's The Best (And Worst) Anime Ending You've Ever Seen?". Anime News Network. March 2, 2016.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side B (in French). Glénat. 2010. pp. 7, 15. ISBN 978-2-7234-7121-3.

- Mike Crandol (June 11, 2002). "Understanding Evangelion". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on December 13, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 5. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 52.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 18. Sony Magazines. p. 14.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side B (in French). Glénat. 2010. pp. 44, 96. ISBN 978-2-7234-7121-3.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side B (in French). Glénat. 2010. p. 41. ISBN 978-2-7234-7121-3.

- Gainax (February 1998). Neon Genesis Evangelion Newtype 100% Collection (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. p. 83. ISBN 4-04-852700-2.

- "Spotlight: Evangelion". Protoculture Additcs. Protoculture Inc. (39): 21. March 1996.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 5. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 34.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side B (in French). Glénat. 2010. p. 70. ISBN 978-2-7234-7121-3.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 5. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 46.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 8. Sony Magazines. p. 45.

- Gualtiero Cannarsi. Evangelion Encyclopedia (in Italian). 6. Dynamic Italia. p. 21.

- Gualtiero Cannarsi. Evangelion Encyclopedia (in Italian). 8. Dynamic Italia. p. 12.

- "第55回 エヴァ雑記「第弐拾弐話 せめて、人間らしく」" (in Japanese). Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Miller, Gerald Alva Jr. (2012). Exploring the Limits of the Human Through Science Fiction. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-137-26285-1.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 22. Sony Magazines. p. 6.

- Gainax, ed. (1997). "溶け合う心が私を壊す". Death & Rebirth Program Book (in Japanese).

- Gainax, ed. (1997). "用語集". The End of Evangelion Theatralical Pamphlet (in Japanese).

- Gainax, ed. (1997). "汚された心". Death & Rebirth Program Book (Special Edition) (in Japanese).

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 12. Sony Magazines. p. 6.

- Poggio 2008, pp. 32-33.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side A (in French). Glénat. 2009. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-2-7234-7120-6.

- Gualtiero Cannarsi. Evangelion Encyclopedia (in Italian). 5. Dynamic Italia. pp. 16–17.

- "新世紀エヴァンゲリオン - Story" (in Japanese). Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Poggio 2008, p. 31.

- Gainax, ed. (1997). "登場人物". Death & Rebirth Program Book (in Japanese).

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 6. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 33.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side B (in French). Glénat. 2010. p. 52. ISBN 978-2-7234-7121-3.

- Poggio 2008, p. 91.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 8. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 4.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 9. Kadokawa Shoten. pp. 6, 14.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side B (in French). Glénat. 2010. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-2-7234-7121-3.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Film Book (in Japanese). 9. Kadokawa Shoten. p. 18.

- Napier, Susan J. (November 2002). "When the Machines Stop: Fantasy, Reality, and Terminal Identity in Neon Genesis Evangelion and Serial Experiments Lain". Science Fiction Studies. 29 (88): 426. ISSN 0091-7729. Retrieved May 4, 2007.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 22. Sony Magazines. p. 23.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 29. Sony Magazines. p. 29.

- Evangelion Chronicle (in Japanese). 25. Sony Magazines. p. 25.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side B (in French). Glénat. 2010. p. 86. ISBN 978-2-7234-7121-3.

- Ogawa, Noelle (December 4, 2019). "Why Asuka is One of the Best Anime Characters of All Time". Crunchyroll. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- Bhardwaj, Himanshu (May 23, 2020). "15 Most Popular Anime Characters – Goku, Naruto, Luffy, and Others Ranked!". Otaku Kart. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- "Recochoku" (in Japanese). Archived from the original on June 1, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- "One Piece's Luffy, DB's Goku Top Fuji TV's Anime/Tokusatsu Hero Poll". Anime News Network. April 5, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- "7 Female Anime Directors Worth Checking Out". Anime News Network. October 1, 2016. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- "Top 10". Animage (in Japanese). Tokuma Shoten. September 1997.

- "Best 100". Animage (in Japanese). Tokuma Shoten. November 1997.

- "Biglobe Poll: Moe Characters That Make You Go Crazy". Anime News Network. June 29, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- "女子が好きな『新世紀エヴァンゲリオン』キャラクターTOP3/ 1位はなんとあの脇役!" (in Japanese). July 24, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- "第18回アニメグランプリ[1996年5月号]". Tokuma Shoten. Archived from the original on October 19, 2010.

- "第19回アニメグランプリ[1997年6月号]". Tokuma Shoten. Archived from the original on October 19, 2010.

- "第20回アニメグランプリ[1998年6月号]". Tokuma Shoten. Archived from the original on October 19, 2010.

- "1996年08月号ベスト10" (in Japanese). Archived from the original on October 25, 2010. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- "Animage" (in Japanese). Tokuma Shoten. March 1997. p. 232. Cite magazine requires

|magazine=(help) - "BEST 10". Animage (in Japanese). Tokuma Shoten. April 1997.

- "BEST 10". Animage (in Japanese). Tokuma Shoten. August 1997.

- "明けましてパクト100". Animage (in Japanese). Tokuma Shoten. February 1998.

- "1998年07月号ベスト10" (in Japanese). Animage. Archived from the original on October 25, 2010. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- "Animage" (in Japanese). Tokuma Shoten. August 1998. p. 229. Cite magazine requires

|magazine=(help) - "あけましてベスト100!". Animage (in Japanese). Tokuma Shoten. February 1999.

- "Newtype" (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. August 2009. p. 172. Cite magazine requires

|magazine=(help) - "Newtype" (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. September 2009. p. 148. Cite magazine requires

|magazine=(help) - "Newtype" (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. October 2009. p. 136. Cite magazine requires

|magazine=(help) - "新世紀エヴァンゲリオン". Newtype (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. March 2010. pp. 24–25.

- "Ranking". Newtype (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. February 2015. p. 105.

- "Japanese Fans Pick The Ladies Of Anime They'd Love To Marry... And The Ones They'd Rather Die Than Marry". Crunchyroll. June 25, 2017. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- Fujie, Kazuhisa; Foster, Martin (2004). Neon Genesis Evangelion: The Unofficial Guide. United States: DH Publishing, Inc. p. 162. ISBN 0-9745961-4-0.

- Aravind, Ajay (December 2, 2020). "Neon Genesis Evangelion: Every Main Character, Ranked By Likability". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- Kogod, Theo (November 8, 2019). "Neon Genesis Evangelion: The 10 Worst Things Asuka Ever Did, Ranked". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- Harcoff, Pete (May 26, 2003). "Neon Genesis Evangelion". Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- See, Raphael. "Neon Genesis Evangelion". T.H.E.M. Anime Reviews. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- Lynzee Loveridge (July 4, 2015). "7 of the Worst Sore Losers". Anime News Network. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Ransey Isler (February 4, 2014). "Top 25 greatest anime characters". IGN. p. 5. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- "10 Greatest Female Pilots in Mecha Anime". April 5, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- "10 Classic Tsundere Characters In Shounen Anime". February 28, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "Evangelion's Asuka Is One of the Most Fascinating Characters in Anime". June 29, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- Shaddock, Chris (January 19, 2021). "Neon Genesis Evangelion: Best & Worst Characters, Ranked". Screen Rant. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- Mitra, Ritwik (January 16, 2021). "Neon Genesis Evangelion: The Main Characters, Ranked From Worst To Best By Character Arc". Screen Rant. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "Top 10 Best Anime Mecha Pilots". WatchMojo. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- J.P. Telotte (2008). The Essential Science Fiction Television Reader. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-0-8131-2492-6.

- "強気だけど弱い可憐な美少女「惣流・アスカ・ラングレー」『新世紀エヴァンゲリオン』" (in Japanese). Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- Patrick Meaney (March 19, 2008). "Neon Genesis Evangelion: End of Evangelion". Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- Pete Harcoff (June 6, 2003). "End of Evangelion". Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- Mike Crandol (September 24, 2002). "Neon Genesis Evangelion: End of Evangelion". Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- Eric Surrell (June 1, 2011). "Evangelion 2.22 You Can (Not) Advance". Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- Abrams, Simon (January 18, 2001). "Evangelion 2.0". Slant Magazine. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- "Evangelion SIM-free smartphones and life-sized figures on sale at 7-Eleven". October 21, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- "Astro Toy With Rob Bricken: Evangelion Aerocat EX". January 25, 2009. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- The Essential Evangelion Chronicle: Side A (in French). Glénat. 2009. pp. 118–127. ISBN 978-2-7234-7120-6.

- "Rock on with Evangelion Guitar Cabinets, Bass Preamp". July 1, 2018. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- "Evangelion Plug Suit-Based Wetsuits for Sale in Japan". January 17, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- "Evangelion characters get their own clothing lines". June 16, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- "Asuka's official underwear sells out quickly on Evangelion's online store". September 24, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- "BOME Asuka Figure Gets US$7,000 Price Tag". September 10, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ""You're so messed up!" Complaints come after broadcaster edits infamous Evangelion scene". August 27, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- Fujie, Kazuhisa; Foster, Martin (2004). Neon Genesis Evangelion: The Unofficial Guide. United States: DH Publishing, Inc. p. 126. ISBN 0-9745961-4-0.

- "ASUKA-アスカ- 新世紀エヴァンゲリオン文庫写真集" (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- "PS2版綾波育成計画withアスカ補完計画" (in Japanese). Archived from the original on March 26, 2012. Retrieved August 21, 2014.

- "Evangelion 2.22, 1.11 Rank #1, #2 on Weekly BD Chart". Anime News Network. June 8, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- "エヴァ芸人・稲垣早希が蜷川実花撮り下ろしで初写真集 ~衣装を脱いだ"素顔"も公開" (in Japanese). November 19, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- "ぱるるの『エヴァ』アスカコスプレが、"ヤバい"と話題に" (in Japanese). July 8, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- "川島海荷 : 綾波レイにコスプレ 村田寛奈はアスカに" (in Japanese). July 29, 2012. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- "Taiwanese Politician Campaigned as Evangelion's Asuka". December 27, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- Gramuglia, Anthony (October 23, 2020). "How Evangelion's Asuka Defined Tsundere Characters for a Generation". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- Gramuglia, Anthony (November 2, 2020). "Rei Vs. Asuka - Who Is Evangelion's Best Girl?". Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- Clements, Jonathan; McCarthy, Helen (2006). The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917 – Revised & Expanded Edition. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press. pp. 259–260. ISBN 1-933330-10-4.

- Theron, Martin (July 31, 2016). "Plastic Memories". Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- Allegra Frank (May 10, 2017). "Heroes of the Storm skins reveal a love for classic anime". Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- "実はけっこうある!?「エヴァ」キャラへ向けた歌!" (in Japanese). June 17, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2020.