Avicephala

Avicephala is a possibly polyphyletic and therefore disused taxon of diapsid reptiles that lived during the Late Permian and Triassic periods. Many species had odd specialized grasping limbs and prehensile tails, adapted to arboreal (and possibly aquatic) lifestyles.

Description

The name "Avicephala" means "bird heads", in reference to the distinctive triangular skulls of these reptiles that mimic the shape of bird skulls. A few avicephalans, such as Hypuronector, even appear to have had pointed, toothless, bird-like beaks. This cranial similarity to birds has led a few scientists to theorize that birds descended from avicephalans like Longisquama, though a majority see the similarity simply as convergence. This similarity may also have led to the possible misidentification of the would-be "first bird", Protoavis.[1]

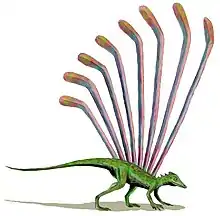

Avicephalans possessed a variety of odd and distinctive characteristics in addition to their bird-like skulls. Some displayed unique dermal appendages, such as the feather-like dorsal plumes of Longisquama, and the laterally-oriented rib-like rods of Coelurosauravus, which supported membranes and may have been used to glide from branch to branch in an arboreal habitat.

Another avicephalan group, the drepanosaurids, featured a suite of bizarre, almost chameleon-like skeletal features. Above the shoulders of most species was a specialized "hump" formed from fusion of the vertebrae, possibly used for advanced muscle attachments to the neck, and allowing for quick forward-striking movement of the head (perhaps to catch insects). Many had derived hands with two fingers opposed to the remaining three, an adaptation for grasping branches. Some individuals of Megalancosaurus (possibly exclusive to either males or females) had a primate-like opposable toe on each foot, perhaps used by one sex for extra grip during mating. Most species had broad, prehensile tails, sometimes tipped with a large "claw", again to aid in climbing. These tails, tall and flat like those of newts and crocodiles, have led some researches to conclude that they were aquatic rather than arboreal. In 2004, Senter dismissed this idea, while Colbert and Olsen, in their description of Hypuronector, state that while other drepanosaurs were probably arboreal, Hypuronector was uniquely adapted to aquatic life.[2] The tail of this genus was extremely deep and non-prehensile – much more fin-like than other drepanosaurs.[3]

History of classification

The various avicephalan groups have been difficult to pin down in terms of their phylogenetic position. Some of these enigmatic reptiles, specifically the drepanosaurids and Longisquama, have been assigned by some researches to the Prolacertiformes.[4] Senter, however, found them to form a group with the coelurosauravids, for which he coined the name Avicephala, as a sister taxon to Neodiapsida (the group which includes all modern diapsids and their extinct relatives).[2]

Within Avicephala, Senter named the group Simiosauria ("monkey lizards") for the extremely derived tree-dwelling forms. Simiosauria was defined as "all taxa more closely related to Drepanosauridae than to Coelurosauravus or Sauria." However, Renesto and colleagues (see below) found drepanosaurids to lie within Sauria, which would make the clade Simiosauria obsolete.

Senter found that Hypuronector, originally described as a drepanosaurid, actually lies just outside that family, along with the primitive drepanosaur Vallesaurus. He also recovered a close relationship between the drepanosaurs Dolabrosaurus and Megalancosaurus.

The following cladogram was found by Senter in his 2004 analysis.[2]

| Avicephala |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Renesto et al. (2010)[5] demonstrated that Senter (2004) cladogram was based on poorly defined characters and dataset. The resulting phylogeny was therefore very unusual compared to any other previous study on drepanosaurs or related taxa. The new cladogram proposed in this last study abandoned both Avicephala (because it is polyphyletic) and Simiosauria, redefining the latter under the PhyloCode as Drepanosauromorpha. Drepanosauromorphs are closely related to the Prolacertiformes, especially genera like Langobardisaurus and Macrocnemus, if not part of the Prolacertiformes. Among the drepanosauromorphs it was defined a more inclusive taxon, Elyurosauria ("lizard with coiled tails"), in order to include all the drepanosaurs with coiled tails, Vallesaurus is thus more derived than Hypuronector (as clearly shown by its morphology). Drepanosaurus and Megalancosaurus are also in a new taxon named Megalancosaurinae.

The alternative cladogram as presented in Renesto et al. (2010).[5]

| Drepanosauromorpha |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Renesto, S. (2000). "Bird-like head on a chameleon body: new specimens of the enigmatic diapsid reptile Megalancosaurus from the Late Triassic of northern Italy." Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia, 106: 157–180. Abstract

- Senter, P. (2004). "Phylogeny of Drepanosauridae (Reptilia: Diapsida)." Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 2(3): 257-268.

- Colbert, E. H., and Olsen, P. E. (2001). "A new and unusual aquatic reptile from the Lockatong Formation of New Jersey (Late Triassic, Newark Supergroup)." American Museum Novitates, 3334: 1-24.

- Renesto, S. (1994). "Megalancosaurus, a possibly arboreal archosauromorph (Reptilia) from the Upper Triassic of northern Italy." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 14(1): 38-52.

- Silvio Renesto, Justin A. Spielmann, Spencer G. Lucas, and Giorgio Tarditi Spagnoli. (2010). The taxonomy and paleobiology of the Late Triassic (Carnian-Norian: Adamanian-Apachean) drepanosaurs (Diapsida: Archosauromorpha: Drepanosauromorpha). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 46:1–81

External links

- Monkey Lizards of the Triassic - An illustrated article on drepanosaurs from HMNH.

- Prof. Silvio Renesto—Vertebrate Paleontology at Insubria University: Research - Images and discussion of Drepanosaurus.

- Prof. Silvio Renesto—Vertebrate Paleontology at Insubria University: Research - Images and discussion of Megalancosaurus.

- Gliding Mechanism in the Late Permian Reptile Coelurosauravus (Eberhard Frey, Hans-Dieter Sues, & Wolfgang Munk) - Abstract and available full text of the article in Science.