Axel jump

The Axel jump, also called the Axel Paulsen jump for its creator, Norwegian figure skater Axel Paulsen, is an edge jump in the sport of figure skating. It is figure skating's oldest and most difficult jump. It is the only competition jump that begins with a forward takeoff, which makes it the easiest jump to identify. A double or triple Axel is required in both the short programs and free skating programs for junior and senior single skaters in all International Skating Union (ISU) competitions. According to The New York Times, the triple Axel "has become more common for male skaters" to perform,[1] although the quadruple Axel has not yet been successfully completed in competition. As of 2020, 12 women have successfully completed the triple Axel in international competition. The Axel has an extra half rotation, which, as figure skating expert Hannah Robbins states, makes a triple Axel "more a quadruple jump than a triple".[2]

| Figure skating element | |

|---|---|

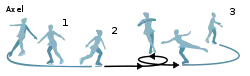

A single Axel jump. | |

| Element name: | Axel jump |

| Alternative name: | Axel Paulsen jump |

| Scoring abbreviation: | A |

| Element type: | Jump |

| Take-off edge: | Forward outside |

| Landing edge: | Back outside |

| Inventor: | Axel Paulsen |

History

The Axel jump, also called the Axel Paulsen jump for its creator, Norwegian figure skater Axel Paulsen, is an edge jump in the sport of figure skating.[3][4] Figure skating historian James Hines calls the Axel "figure skating's most difficult jump".[5] It is the only competition jump that begins with a forward takeoff, which makes it the easiest jump to identify. Skaters will often perform a double or triple Axel, followed by a simpler jump, during combination jumps.[6]

In competitions, the base value of a single Axel is 1.10; the base value of a double Axel is 3.30; the base value of a triple Axel is 8.00; and the base value of a quadruple Axel is 12.50.[7] A double or triple Axel is required in both the short programs and free skating programs for junior and senior single skaters in all International Skating Union (ISU) competitions.[8] The Axel jump is the most studied jump in figure skating.[9]

Firsts

The first skater to accomplish an Axel was its creator, Axel Paulsen, in 1882 at the first international figure skating competition, which was held in Vienna.[5] Hines, who called Paulsen "progressive" for inventing it, stated that he did it "as a special figure".[10] By the mid-1920s, the Axel was the only jump that was not being doubled.[5] Professional German skater Charlotte Oelschlägel, during the early 1900s, was the first woman to include an Axel in her programs; Hines reported that she would terminate the Axel with her "famous fade-away ending",[11] the Charlotte spiral, a move she invented.[12] In the early 1920s, Sonja Henie from Norway was the first female skater to perform an Axel in competition.[13] Hines also reports that in the 1930s, Austrian skater Felix Kaspar, who was known for his athleticism, performed Axels that were four feet high and 20 feet from takeoff to landing; Hines stated that "there is little doubt in the minds of those who saw him that had the technique then been known, he probably could have easily performed triple or even quadruple jumps".[14]

American Dick Button was the first skater to complete a double Axel in competition, at the 1948 Winter Olympic Games.[15] American Carol Heiss was the first woman to perform a double Axel, in 1953.[16] The first triple Axel in competition was performed by Canadian Vern Taylor at the 1978 World Championships.[13] The first male skater to complete a triple Axel during the Olympics was Canadian skater Brian Orser in 1984.[1] The first throw triple Axel was performed by American pair skaters Rena Inoue and John Baldwin, at the 2006 U.S. National Championships.[17] As of 2020, the quadruple Axel has not been successfully completed in competition.[18]

According to The New York Times, the triple Axel "has become more common for male skaters" to perform.[1] The first female skater to complete a triple Axel was Japanese skater Midori Ito, at the 1989 World Championships.[13] Only three women have completed the triple Axel during the Olympics: Ito in 1992, Japanese skater Mao Asada in 2010 and 2014, and American skater Mirai Nagasu in 2018.[19] Tonya Harding was the first American female skater to complete the triple Axel in competition, at the 1991 U.S. Championships; it was another 10 years before another female skater attempted it.[20] As of 2020, 12 women have successfully completed the triple Axel in international competition. They are: Midori Ito, Tonya Harding, Ludmila Nelidina, Yukari Nakano, Mao Asada, Elizaveta Tuktamysheva, Rika Kihira, Mirai Nagasu, Alysa Liu, Alena Kostornaia, You Young, and Anastasia Shabotova [21]

Execution

The Axel is an edge jump, which means that the skater must spring into the air from bent knees.[22] It is the oldest but most difficult figure skating jump.[23] A "lead-up" to the Axel is the waltz jump, a half-revolution jump and the first jump that skaters learn.[24] The Axel has three phases: the entrance phase (which ends with the takeoff), the flight phase, when the skater rotates into the air, and the landing phase, which begins when the skater's blade hits the ice and ends when they are "safely skating backwards on the full outside edge with one leg behind in the air".[9] According to researcher Anna Mazurkiewicz and her colleagues, the most important parts of the entrance phase is the transition phase (also called the pre-takeoff phase) and the takeoff itself.[25] The jump has a forward takeoff, approached with a series of backward crossovers in either the opposite or the same direction to the jump's rotation, followed by a step forward onto the forward outside takeoff edge.

The skater must also approach the jump typically from the left forward outside edge of the skate, enabling them to step forward. The skater then kicks through with their free leg, helping them to jump into the air. The skater must land on the right back outside edge of the skate. The change in foot required to complete the Axel means that the skater's centre of gravity must be transferred from the left side to the right, while rotating in the air, to reach the correct position to land.[23] As a result, the Axel has an extra half-rotation, which, as figure skating expert Hannah Robbins states, "makes a triple Axel more a quadruple jump than a triple":[2] the single Axel consists of one-and-a-half revolutions, the double Axel consists of two-and-half revolutions, and the triple Axel consists of three-and-a-half revolutions.[3][13]

Sports reporter Nora Princiotti states, about the triple Axel, "It takes incredible strength and body control for a skater to get enough height and to get into the jump fast enough to complete all the rotations before landing with a strong enough base to absorb the force generated".[22] According to American skater Mirai Nagasu, "falling on the triple Axel is really brutal".[19] It has been shown that the more skilled skaters have greater takeoff velocities and jump lengths. When skaters perform double Axels, they exhibit greater rotations during the flight phase, take off in more closed positions, and attain greater rotational velocities than when performing single Axels. They also increase their turns not by increasing the time in the air, but by increasing their rotational velocity when performing single, double, and triple Axels.[26] According to researcher D.L. King, the key to executing a successful triple Axel is "achieving a high rotational velocity by generating angular momentum at take-off and minimising the moment of inertia about the spin axis".[26]

References

- Victor, Daniel (12 February 2018). "Mirai Nagasu Lands Triple Axel, a First by an American Woman at an Olympics". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- Robbins, Hannah (11 February 2018). "Triple Axel new ladies' figure skating staple". The Collegian. Tulsa, Oklahoma: University of Tulsa. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- "Identifying Jumps" (PDF). U.S. Figure Skating. p. 1. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- Hines (2015), p. 49

- Hines (2011), p. xxxii

- Abad-Santos, Alexander (5 February 2014). "A GIF Guide to Figure Skaters' Jumps at the Olympics". The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "Communication No. 2168: Single & Pair Skating". Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. 23 May 2018. p. 2. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- "Special Regulations & Technical Rules Single & Pair Skating and Ice Dance 2018". International Skating Union. June 2018. pp. 104–109. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- Mazurkiewicz et al., p. 3

- Hines (2011), p. 132

- Hines (2015), p. 185

- Hines (2011), p. 170

- Media Guide, p. 13

- Hines (2015), p. 113

- Pucin, Diane (7 January 2002). "Button Has Never Been Known to Zip His Lip". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- Judd, Ron C. (2001). The Winter Olympics: An Insider's Guide to the Legends, the Lore, and the Games. Seattle, Wash.: The Mountaineer Books. p. 100.

- Media Guide, p. 15

- Media Guide, p. 14

- Calfas, Jennifer (12 February 2018). "Why Mirai Nagasu's Historic Triple Axel at the Olympics Is Such a Big Deal". Time. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- Dubreuil, Jim; Rakowski, Cat; Rachel, Tesler (10 January 2018). "Tonya Harding on landing her history-making triple Axel: 'Everything about life after that point became confusing'". ABC.com. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- Дикий, Макс (18 October 2020). "14-year-old Shabotova jumped a triple axel at the Budapest Trophy". Sports Ru. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- Princiotti, Nora (12 February 2018). "What is a triple Axel? And why is it so hard for figure skaters to pull off?". Boston.com. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- Kestnbaum, Ellyn (2003). Culture on Ice: Figure Skating and Cultural Meaning. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. p. 285. ISBN 0819566411.

- Hines, James R. (2006). Figure Skating: A History. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. p. 101. ISBN 0-252-07286-3.

- Mazurkiewicz et al., p. 5

- Mazurkiewicz et al., p. 4

Works cited

- Hines, James R. (2011). Historical Dictionary of Figure Skating. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6859-5.

- Hines, James R. (2015). Figure Skating in the Formative Years: Singles, Pairs, and the Expanding Role of Women. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03906-5.

- "ISU Figure Skating Media Guide 2018/19". International Skating Union. 20 September 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- Mazurkiewicz, Anna, Dagmara Twańsak, and Czesław Urbanik (July 2018). "Biomechanics of the Axel Paulsen Figure Skating Jump." Polish Journal of Sport and Tourism 25 (2):3-9. DOI: 10.2478/pjst-2018-0007.