Ball (dance party)

A ball is a formal dance party characterised by a banquet followed by social dance that includes ballroom dancing.

Etymology

The word ball derives from the Latin word ballare, meaning 'to dance', and bal was used to describe a formal dancing party in French in the 12th century. The ballo was an Italian Renaissance word for a type of elaborate court dance, and developed into one for the event at which it was performed. The word also covered performed pieces like Il ballo delle ingrate by Claudio Monteverdi (1608). French developed the verb baller, and the noun bal for the event—from where it swapped into languages like English or German—, and bailar, the Spanish and Portuguese verbs for 'to dance' (although all three Romance languages also know danser, danzar, and dançar respectively). Catalan uses the same word, ball, for the dance event. Ballet developed from the same root.

History

.JPG.webp)

Elite formal dances in the Middle Ages often included elements of performance, which gradually increased until the 17th century, often reducing the amount of dancing by the whole company. Medieval dance featured many group dances, and this type of dance lasted throughout Baroque dance until at least the 19th century, when dances for couples finally took over the formal dance. Group dances remained in some cases, and often dances for couples were danced in formation. Many dances originated in popular forms, but were given elegant formalizations for the elite ball. Dancing lessons were considered essential for both sexes.

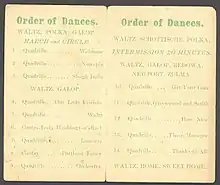

As the ballets de cour at the French court, part social dance and part performance, declined in the later 17th century, the formal ball took over as a grand and large evening social event. Although most were strictly by invitation only, with printed invitations coming in the mid-18th century, some balls were public, either with tickets sold, or in cases such as the celebration of royal events, open to anyone who was appropriately dressed. It was at The Yew Tree Ball at Versailles in 1745, a public ball celebrating the royal wedding of his son, that Madame de Pompadour was able to meet the disguised King Louis XV, dressed as a hedge.[1] The distinction between a less formal "dance" and a formal "ball" was established very early; improvised dancing after dinner, as occurs in Jane Austen's Persuasion (1818) was also common.[2] In the 19th century the dance card became common; here ladies recorded the names of the men who had booked a particular dance with them.

The grandest balls were at the French court in the Chateau de Versailles, with others in Paris. At royal balls, most guests did not expect to be able to dance, at least until very late in the night.[3] Indeed, throughout the period dancers seem to have been a minority of the guests, and mostly drawn from the young and unmarried. Many guests were happy to talk, eat, drink and watch. A bal blanc ("white ball", as opposed to a bal en blanc, merely with an all-white theme) was or is only for unmarried girls and their chaperones, with the women all in white dresses. The modern debutante ball may or may not continue these traditions.

Georgian England

A well-documented ball occurred at Kingston Lacy, Dorset, England, on 19 December 1791. The occasion was to celebrate the completion of major alterations to the house and the event was organised by Frances Bankes, wife of Henry Bankes, owner of the house. The event involved 140 guests, with dancing from 9pm to 7am, interrupted by supper at 1am.[4] They would all have had dinner at home many hours earlier, before coming out. Other, grander, balls served supper even later, up to 3.30 a.m., at an 1811 London ball given by the Duchess of Bedford.[5]

The Duchess of Richmond's ball in Brussels in 1815, dramatically interrupted by news of Napoleon's advance, and most males having to leave to rejoin their units for the Battle of Waterloo the next day, has been described as "the most famous ball in history".[6]

See also

Notes

- Wallace, 13-16

- Wallace, 19

- Wallace, 12-13

- "Frances Bankes' ball at Kingston Lacy 19 December 1791 (From Regency History)". Regency History.net. Retrieved 2014-01-03.

- Day, Ivan, "Pride and Prejudice - Having a Ball", Food Jottings

- Hastings, Max (1986), "Anecdote 194", The Oxford Book of Military Anecdotes, Oxford University Press US, pp. 230, ISBN 978-0-19-520528-2

References

- Wallace, Carol McD.; et al. (1986). Dance: a very social history. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870994869.

External links

Media related to Balls (dance) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Balls (dance) at Wikimedia Commons