Bandar Siraf

Bandar Siraf (Persian: بندر سیراف, also Romanized as Bandar-e Sīraf; also known as Sīraf, Ţāherī, and Tāhiri; also known as Bandar-e Ţāherī and Bandar-i Ţāhirī, بندر طاهری - "Bandar" meaning "Port" in Persian)[2] is a city in the Central District of Kangan County, Bushehr Province, Iran. At the 2006 census, its population was 3,500, in 722 families.

Bandar Siraf (Bandar Taheri)

بندر سیراف بندر طاهری | |

|---|---|

City | |

Beachfront in Siraf | |

Bandar Siraf Location in Iran | |

| Coordinates: 27°40′00″N 52°20′33″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Bushehr |

| County | Kangan |

| Bakhsh | Central |

| Population (2016 Census) | |

| • Total | 6,992 [1] |

| Time zone | UTC+3:30 (IRST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+4:30 (IRDT) |

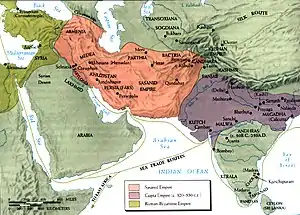

According to legend, Siraf was an ancient Sassanid port, destroyed around 970 CE,[3] which was located on the north shore of the Persian Gulf in what is now the Iranian province of Bushehr. Its ruins are approximately 220 km east of Bushire, 30 km east from Kangan city, and 380 km west of Bandar Abbas.[4] Siraf controlled three ports: Bandar-e-Taheri, Bandar-e-Kangan and Bandar-e-Dayer.[5] The Persian Gulf was used as a shipping route between the Arabian Peninsula and India over the Arabian Sea. Small boats, such as dhows, could also make the long journey by staying close to the coast and keeping land in sight.[6]

The port was known as Tahiri until in 2008 the government of Iran changed the official name of the city back to Bandar Siraf.

History

The port was known as Siraf in ancient times. At the time of the silk road, most of the commerce towards Asia was performed through Siraf. Jewish oral history[7] claims that at that time, all the inhabitants of Siraf were Jewish merchants. When Arabs invaded Persia, they forced the Jewish inhabitants to become Muslims. Furthermore, they changed the name to Taheri, which means pure in Arabic. The Arabs considered Jews as ritually impure(نجس) and since they thought converting to Islam has made them ritually pure (Tahir طاهر) they changed the name of the port to Tahiri.[7]

According to David Whitehouse, one of the first archaeologists to excavate the ancient ruins of Siraf, marine trade between the Persian Gulf and Far East lands began to flourish at this port because of the vast expansion of trade in consumer goods and luxury items at the time. The first contact between Siraf and China occurred in 185 AD. However, over time trade routes shifted to the Red Sea and Siraf was forgotten.[8] Siraf as a port was founded in the 9th century, and continued its trade activity till the 15th century, then fell into rapid decline.

The historical importance of Siraf to ancient trade is only now being realized. Discovered there in past archaeological excavations are ivory objects from east Africa, pieces of stone from India, and lapis from Afghanistan. Siraf dates back to the Parthian era.[9]

David Whitehouse also found evidence that the earliest mosque at Siraf dates to the 9th century and there are remains from the Parthian and Sassanid eras not far from the city. He found ruins of a congregational mosque surrounded by many smaller mosques.[10] There are ruins of the luxurious houses of extremely rich traders who made their wealth through the port's success.[11] Siraf served an international clientele of merchants including those from South India ruled by the Western Chalukyas dynasty who were feasted by wealthy local merchants during business visits. An indicator of the Indian merchants' importance in Siraf comes from records describing dining plates reserved for them.[12] There is historical evidence of Sassanian maritime trade with the Gulf of Cambay in the modern day province of Gujarat,[13] as fragments of Indian red polished ware, of predominantly Gujarati provenance dating to the 5th and 6th centuries were found at coastal sites on the northern shores of the Persian Gulf, and especially at Siraf.[14]

Many of the finds (over 16,000 in all) excavated at Siraf by Whitehouse and his archaeological team in the 1960s and 1970s are kept in the British Museum in London.[15]

Siraf has not yet been registered on the list of national heritage sites of Iran. This is needed so that it will be preserved and maintained in the future.[16]

Gallery

Ancient crypts of Siraf

Ancient crypts of Siraf landscape of Ancient Region of Siraf

landscape of Ancient Region of Siraf

Further reading

- S.M.N. Priestman ‘The rise of Siraf: long-term development of trade emporia within the Persian Gulf’. In Proceedings of the International Congress of Siraf Port, November 14–16, 2005, Bushehr Branch of Iranology Foundation & Bushehr University of Medical Sciences, Bushehr, 2005, 137-56

- V.F. Piacentini, Merchants, Merchandise and Military Power in the Persian Gulf (Suriyanj/Shakriyaj-Siraf), Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei (Rome), Serie IX, Vol. III(2), 1992.

- Nicholas Lowick, Siraf XV. The Coins and Monumental Inscriptions, The British Institute of Persian Studies, London, 1985.

- D. Whitehouse, Siraf III. The Congregational Mosque and Other Mosques from the Ninth to the Twelfth Centuries, The British Institute of Persian Studies, London, 1980.

- D. Whitehouse, ‘Excavations at Siraf. First-Sixth Interim Reports’, Iran 6-12 (1968–74).

References

- https://www.amar.org.ir/english

- Bandar Siraf can be found at GEOnet Names Server, at this link, by opening the Advanced Search box, entering "-3086632" in the "Unique Feature Id" form, and clicking on "Search Database".

- Boulnois, Luce (2005). Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants. Hong Kong: Odyssey Books. p. 68. ISBN 962-217-721-2.

- "Siraf". sirafcongress. Archived from the original on 2007-03-10. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- "Ancient Cities and Archaeological Hills, Bushehr". Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- "The Seas of Sindbad". Archived from the original on 2007-02-08. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- Trua, Oral history of the Iranian Jews, Homa Sarshar, Center for Iranian Jewish oral history, 1996, Page 223.

- "Siraf, a Legendary Ancient Port". Cultural Heritage News Agency. Archived from the original on 2007-08-20. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- "Foreign Experts Talk of Siraf History". Cultural Heritage News Agency.

- "Siraf". archnet.org. Archived from the original on 2003-06-10. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- "Siraf, a Legendary Ancient Port". Iranian News. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- Sastri (1955), p302

- Pia Brancaccio (2010). The caves at Aurangabad : Buddhist art in transformation. Leiden: Brill. p. 165. ISBN 978-90-04-18525-8. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "GUJARAT (Skt. Gurjaṛ), a province of India on its northwestern coastline". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

Maritime contacts between Gujarat and the Persian Gulf region reach back to the period of Indus Valley civilization (ca. 2500-1500 B.C.). The port of Lothal at the head of the Gulf of Cambay, as well as other excavations in Gujarat, reveal the extent of Gujarat’s earliest commercial contacts with the west (Rao, pp. 39-78, 114-26; Dani and Masson, pp. 312-18).

- British Museum Collection

- "World Famous Archaeologists Attend Siraf Conference". Cultural Heritage News Agency. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- Nilakanta Sastri, K.A. (1955). A History of South India, OUP, New Delhi (Reprinted 2002) ISBN 0-19-560686-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bandar Siraf. |