Barley Hall

Barley Hall is a reconstructed medieval townhouse in the city of York, England. It was built around 1360 by the monks of Nostell Priory near Wakefield and extended in the 15th century. The property went into a slow decline and by the 20th century was sub-divided and in an increasingly poor physical condition. Bought by the York Archaeological Trust in 1987, it was renamed Barley Hall and heavily restored in a controversial project to form a museum. It is open to the public and hosts exhibitions.[1]

| Barley Hall | |

|---|---|

The interior of the Great Hall | |

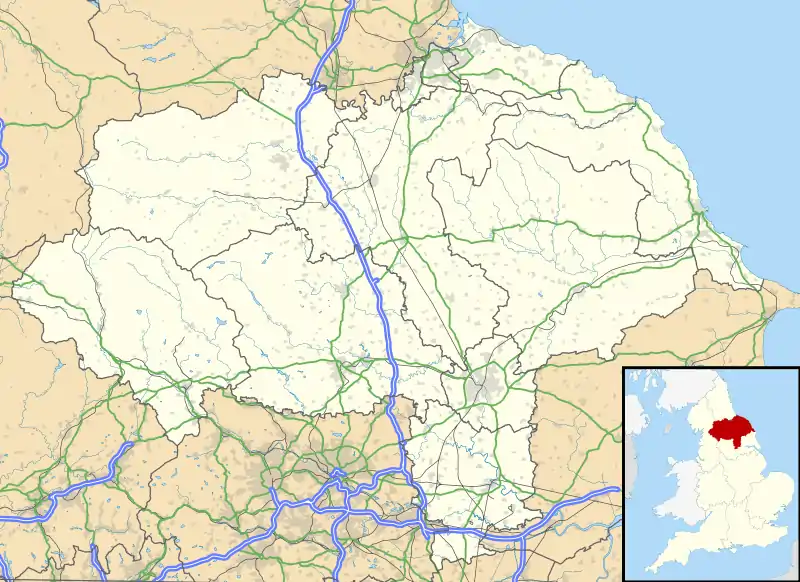

Shown within North Yorkshire | |

| General information | |

| Address | 2 Coffee Yard |

| Town or city | York |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 53.96093°N 1.08264°W |

| Construction started | 1360 |

| Renovated | 1990-3 |

| Owner | York Archaeological Trust |

| Technical details | |

| Structural system | Timber framing |

| Renovating team | |

| Renovating firm | McCurdy & Co |

History

14th – 20th centuries

The earliest parts of the building were constructed by Thomas de Dereford, prior of Nostell Priory, around 1360.[2] The priory was important in Yorkshire, and the monks used the building as a hospice, or townhouse when visiting the city.[2] By the 1430s, however, the priory had fallen on hard times and the monks decided to rent the building out to raise additional revenue.[2] Around this time there was new building work on the site, involving the poor-quality reconstruction of parts of the great hall.[2] In the 1460s the building was rented to William Snawsell, a prominent local goldsmith, who paid 53 shillings and 4 pence for the property. This was a very high rent for the period.[2] Snawsell was a supporter of Richard III during the troubled period of the Wars of the Roses and had given up the property by 1489.[2]

The priory was closed in the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536-1541) and the later history of Barley Hall is less clear.[2] By the 17th century the building had been divided into smaller units, with part of it turned into an alleyway.[3] The once internal corridor is a shortcut from Stonegate to Swinegate and is still a public right of way.[4] By the Victorian era, the property had been subdivided into yet smaller units, partitioned by brick walls, and this pattern of use continued into the 20th century.[2] By the 1970s, the property was used by a local plumber as a storage unit and showroom.[2]

Late 20th – 21st centuries

By the early 1980s, the building was in a dangerously unsafe condition and was scheduled for demolition to make way for offices and apartments.[2] As part of this process, however, the medieval architecture of the building was rediscovered in 1980; the site was sold for redevelopment in 1984 and then purchased by the York Archaeological Trust in 1987 when a further process of archaeological investigation began to inform a decision on the final use of the site.[5]

The decision on what to do with the building proved controversial.[6] Its original wooden timbers had degraded significantly. Only 30% were still usable and the site had been extensively altered since the medieval period.[7] The Trust decided to reconstruct the building as it might have appeared in 1483, with the intention of converting it into a museum, naming it Barley Hall after the Trust's chairman, Professor Maurice Barley.[2] The post-medieval fabric of the building was largely destroyed and a new timber frame was built off-site and then moved into York over a ten-day period, a challenging operation due to the physical constraints of the immediate neighborhood.[8] Replica furniture and fittings were created for the property, based on an inventory made in 1478.[9] Supporters of the scheme, including English Heritage, viewed this as an attempt to produce an innovative way of presenting the past, similar to the Trust's work at the nearby Jorvik Viking Centre.[10] The care and accuracy of the work was praised and the new museum received a generally positive public reaction.[11]

Critics of the reconstruction raised concerns over the nature of the preservation work.[12] Academic Raphael Samuel noted that the restoration was heavily influenced by the late-20th century tradition of living history, in which "reinterpretation" gives way to "retrofitting", and where the past is "faked up to be more palatable than the here and now".[9] The chairman of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings critiqued the work as producing a replica, rather than a restored building, condemned the destruction of the later periods of the hall and noted that it was "another contribution to our Disneyland heritage".[6] Historian Sarah Beckwith suggests that York is now so heavily "museumized that very few of its features escape the construction of an imaginary and commodified past", a problem she argues is typified by Barley Hall.[13]

Architecture

On the ground floor, Barley Hall comprises several rooms.[14] The storeroom, used as an admissions area, contains a large quantity of original 1360 woodwork, which leads onto a second storeroom, now called the Steward's room.[14] At the heart of the building is the Great Hall, a 1430 construction, decorated on the basis of equivalents elsewhere in the city of York.[14] The building also includes a pantry and a buttery.[14] On the first floor is the parlour, which overlooks the hall, a gallery, and several bedchambers.[14] Barley Hall is a grade II listed building.[15]

Exhibitions

Exhibitions have included:

- "Plague, Poverty And Prayer", which opened in the hall in 2013, designed by children's author Terry Deary and using costumes from the BBC's Horrible Histories television programme.[16]

- Costumes from the 2015 TV series Wolf Hall. The series was nominated for a BAFTA award for costume design,[17] and the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Period Costumes.

Bibliography

- Beckwith, Sarah. (2001) Signifying God: Social Relation and Symbolic Act in the York Corpus Christi Plays. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-04133-9.

- Gerrard, Christopher M. (2003) Medieval Archaeology: Understanding Traditions and Contemporary Approaches. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-23463-4.

- Holloway, J. Christopher and Neil Taylor. (2006) The Business of Tourism. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-273-70161-3.

- Roskams, S. and M. Whyman. (2007) Yorkshire Archaeological Research Framework: research agenda. London: English Heritage.

- Samuel, Raphael. (1996) Theatres of Memory. London: Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-077-1.

References

- "What's on". Barley Hall. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- Society Members Form Group to Aid York's Hidden Ricardian Treasure Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Ricardian Friends of Barley Hall, accessed 4 June 2011.

- Historic Record Archived 5 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Barley Hall, the York Archaeological Trust, accessed 4 June 2011.

- "Barley Hall historical record". Barley Hall. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- Society Members Form Group to Aid York's Hidden Ricardian Treasure Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Ricardian Friends of Barley Hall, accessed 4 June 2011; Historic Record Archived 5 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Barley Hall, the York Archaeological Trust, accessed 4 June 2011.

- Holloway and Taylor, p.590.

- Recreating Barley Hall Archived 3 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Barley Hall, the York Archaeological Trust, accessed 4 June 2011.

- Gerrard, p.214; Barley Hall, Coffee Yard, York: Reconstruction of 14th century monastic hospice Archived 14 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine, McCurdy and Co. Ltd, accessed 4 June 2011.

- Samuel, p.195.

- Roskams and Whyman, p.15.

- Holloway and Taylor, p.590; Gerrard, p.214.

- Gerrard, p.214.

- Beckwith, p.14.

- Welcome to Barley Hall leaflet Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Barley Hall, York Archaeological Trust, accessed 5 June 2011.

- Barley Hall 2, York, British Listed Buildings, accessed 5 June 2010.

- Spotlight on 'horrible history' at York exhibition, Stephen Lewis, The Press, accessed 14 November 2014; Plague, Poverty and Prayer: A Horrid History with Terry Deary Archived 30 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Barley Hall, the York Archaeological Trust, accessed 14 November 2014.

- "TV craft (costume design)".

External links

- Official website

Media related to Barley Hall, York at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Barley Hall, York at Wikimedia Commons