Basement membrane

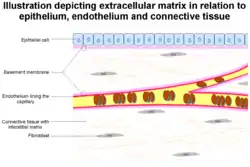

The basement membrane is a thin, pliable sheet-like type of extracellular matrix, that provides cell and tissue support and acts as a platform for complex signalling.[1][2] The basement membrane sits between epithelial tissues including mesothelium and endothelium, and the underlying connective tissue.[3][4]

| Basement membrane | |

|---|---|

The epithelium and endobasement membrane in relation to epithelium and endothelium. Also seen are other extracellular matrix components | |

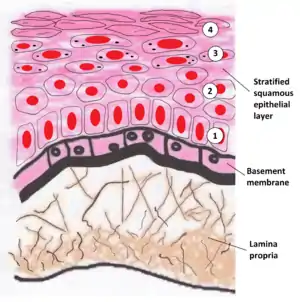

Image showing the basement membrane of the lining of the mouth, which separates the lining (epithelium) from a loose layer of connective tissue (the lamina propria) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | membrana basalis |

| MeSH | D001485 |

| TH | H2.00.00.0.00005 |

| FMA | 63872 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

Structure

As seen with the electron microscope, the basement membrane is composed of two layers, the basal lamina and the reticular lamina.[4] The underlying connective tissue attaches to the basal lamina with collagen VII anchoring fibrils and fibrillin microfibrils.[5]

The basal lamina layer can further be subdivided into two layers based on their visual appearance in electron microscopy. The lighter-colored layer closer to the epithelium is called the lamina lucida, while the denser-colored layer closer to the connective tissue is called the lamina densa. The electron-dense lamina densa layer is about 30–70 nanometers thick and consists of an underlying network of reticular collagen IV fibrils which average 30 nanometers in diameter and 0.1–2 micrometers in thickness and are coated with the heparan sulfate-rich proteoglycan perlecan.[6] In addition to collagen, this supportive matrix contains intrinsic macromolecular components. The lamina lucida layer is made up of laminin, integrins, entactins, and dystroglycans. Integrins are a key component of hemidesmosomes which serve to anchor the epithelium to the underlying basement membrane.

To represent the above in a visually organised manner, the basement membrane is organized as follows:

- Epithelial/mesothelial/endothelial tissue (outer)

- Basement membrane

- Basal lamina

- Lamina lucida

- Lamina densa

- collagen IV (coated with perlecan, rich in heparan sulfate)

- Attaching proteins (between the basal and reticular laminae)

- collagen VII (anchoring fibrils)

- fibrillin (microfibrils)

- Lamina reticularis

- Basal lamina

- Connective tissue (Lamina propria)

Function

The primary function of the basement membrane is to anchor down the epithelium to its loose connective tissue (the dermis or lamina propria) underneath. This is achieved by cell-matrix adhesions through substrate adhesion molecules (SAMs).

The basement membrane acts as a mechanical barrier, preventing malignant cells from invading the deeper tissues.[7] Early stages of malignancy that are thus limited to the epithelial layer by the basement membrane are called carcinoma in situ.

The basement membrane is also essential for angiogenesis (development of new blood vessels). Basement membrane proteins have been found to accelerate differentiation of endothelial cells.[8]

The most notable examples of basement membranes is the glomerular basement membrane of the kidney, by the fusion of the basal lamina from the endothelium of glomerular capillaries and the podocyte basal lamina,[9] and between lung alveoli and pulmonary capillaries, by the fusion of the basal lamina of the lung alveoli and of the basal lamina of the lung capillaries, which is where oxygen and CO

2 diffusion happens (gas exchange).

As of 2017 many other roles for basement membrane have been found that include blood filtration and muscle homeostasis.[1]

Clinical significance

Some diseases result from a poorly functioning basement membrane. The cause can be genetic defects, injuries by the body's own immune system, or other mechanisms.[10] Diseases involving basement membranes at multiple locations include:

- Genetic defects in the collagen fibers of the basement membrane, including Alport syndrome and Knobloch syndrome

- Autoimmune diseases targeting basement membranes. Non-collagenous domain basement membrane collagen type IV is autoantigen (target antigen) of autoantibodies in the autoimmune disease Goodpasture's syndrome.[11]

- A group of diseases stemming from improper function of basement membrane zone are united under the name epidermolysis bullosa.[12]

In histopathology, a thickened basement membrane indicates mainly systemic lupus erythematosus or dermatomyositis, but also possibly lichen sclerosus.[13]

See also

References

- Pozzi, A; Yurchenco, PD; Iozzo, RV (January 2017). "The nature and biology of basement membranes". Matrix Biology. 57–58: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2016.12.009. PMC 5387862. PMID 28040522.

- Sekiguchi, R; Yamada, KM (2018). "Basement Membranes in Development and Disease". Current Topics in Developmental Biology. 130: 143–191. doi:10.1016/bs.ctdb.2018.02.005. ISBN 9780128098028. PMC 6701859. PMID 29853176.

- Kierszenbaum, Abraham; Tres, Laura (2012). Histology and Cell Biology, An Introduction to Pathology (3rd ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-07842-9.

- Tortora, G; Derrickson, B (2012). Principles of anatomy & physiology (13th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. pp. 117–118. ISBN 9780470646083.

- Paulsson M (1992). "Basement membrane proteins: structure, assembly, and cellular interactions". Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 27 (1–2): 93–127. doi:10.3109/10409239209082560. PMID 1309319. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13.

- Noonan DM, Fulle A, Valente P, et al. (December 1991). "The complete sequence of perlecan, a basement membrane heparan sulfate proteoglycan, reveals extensive similarity with laminin A chain, low density lipoprotein-receptor, and the neural cell adhesion molecule". J. Biol. Chem. 266 (34): 22939–47. PMID 1744087.

- Liotta LA, Tryggvason K, Garbisa S, Hart I, Foltz CM, Shafie S (March 1980). "Metastatic potential correlates with enzymatic degradation of basement membrane collagen". Nature. 284 (5751): 67–8. Bibcode:1980Natur.284...67L. doi:10.1038/284067a0. PMID 6243750. S2CID 4356057.

- Kubota Y, Kleinman HK, Martin GR, Lawley TJ (October 1988). "Role of laminin and basement membrane in the morphological differentiation of human endothelial cells into capillary-like structures". J. Cell Biol. 107 (4): 1589–98. doi:10.1083/jcb.107.4.1589. PMC 2115245. PMID 3049626.

- "Sect. 7, Ch. 4: Basement Membrane". 1 April 2008. Archived from the original on 1 April 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2018.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Henig, Robin Marantz (February 22, 2009). "What's Wrong With Summer Stiers?". New York Times. Archived from the original on November 9, 2016.

- Janeway, Charles; Janeway, Charles A. (2001). Immunobiology (5th ed.). Garland. ISBN 978-0-8153-3642-6.

- Bardhan, Ajoy; Bruckner-Tuderman, Leena; Chapple, Iain L. C.; Fine, Jo-David; Harper, Natasha; Has, Cristina; Magin, Thomas M.; Marinkovich, M. Peter; Marshall, John F.; McGrath, John A.; Mellerio, Jemima E. (2020-09-24). "Epidermolysis bullosa". Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 6 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0210-0. ISSN 2056-676X.

- LeBoit, Philip E (2000). "A Thickened Basement Membrane is a Clue to … Lichen Sclerosus!". The American Journal of Dermatopathology. 22 (5): 457–458. doi:10.1097/00000372-200010000-00014. ISSN 0193-1091. PMID 11048985.

Further reading

- Kefalides, Nicholas A.; Borel, Jacques P., eds. (2005). Basement membranes: cell and molecular biology. Gulf Professional Publishing. ISBN 978-0-12-153356-4.