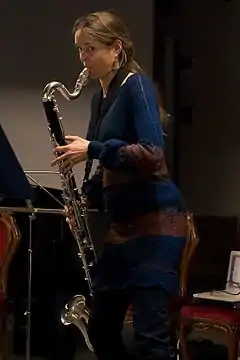

Bass clarinet

The bass clarinet is a musical instrument of the clarinet family. Like the more common soprano B♭ clarinet, it is usually pitched in B♭ (meaning it is a transposing instrument on which a written C sounds as B♭), but it plays notes an octave below the soprano B♭ clarinet.[1] Bass clarinets in other keys, notably C and A, also exist, but are very rare (in contrast to the regular A clarinet, which is quite common in classical music). Bass clarinets regularly perform in orchestras, wind ensembles/concert bands, occasionally in marching bands, and play an occasional solo role in contemporary music and jazz in particular.

B♭ bass clarinet | |

| Woodwind instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification |

woodwind instrument |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 422.211.2-71 (Single-reeded aerophone with keys) |

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

|

Clarinet family | |

| More articles or information | |

| |

Someone who plays a bass clarinet is called a bass clarinetist.[2]

Description

Most modern bass clarinets are straight-bodied, with a small upturned silver-colored metal bell and curved metal neck. Early examples varied in shape, some having a doubled body making them look similar to bassoons. The bass clarinet is fairly heavy and is supported either with a neck strap or an adjustable peg attached to its body. While Adolphe Sax imitated its upturned metal bell in his design of the larger saxophones, the two instruments are fundamentally different. Bass clarinet bodies are most often made of grenadilla (African Blackwood) or (more commonly for student-instruments) plastic resin, while saxophones are typically made of metal. (Metal bass clarinets exist,[3] but are rare.) More significantly, all clarinets have a bore that is basically the same diameter along the body. This cylindrical bore differs from the saxophone's conical one and gives the clarinet its characteristic tone, causing it to overblow at the twelfth compared with the saxophone's octave.

A majority of modern bass clarinets, like other clarinets in the family, have the Boehm system of keys and fingering. However, bass clarinets are also manufactured in Germany with the Oehler system of keywork, which is most often known as the 'German" system in the US, because it is commonly used in Germany and Austria, as well as Eastern Europe and Turkey; bass clarinets produced with the Oehler system's predecessor, the Albert system, are still in use, particularly in these areas.

Most modern Boehm system bass clarinets have an "extension" key allowing them to play to the (written) E♭. This key was originally added to allow easy transposition of parts for the relatively rare bass clarinet pitched in A, but it now finds significant use in concert band and other literature. A significant difference between soprano and bass clarinet key work is a key pad played by the left-hand index finger with a vent that may be uncovered for certain high notes. This allows a form of "half-hole" fingering that allows notes in higher registers to be played on the instrument. In addition, older bass clarinets have two register keys, one for middle D♯ and below, the other for middle E and higher. Newer models typically have an automatic register key mechanism, where a single left thumb key commands the two vent holes. Depending on whether the right hand ring finger (used in fingerings for middle D♯ and below) is down or up, the lower or upper vent hole will open.

Many professional or advanced bass clarinet models extend down to a low C (sounding B♭, identical to the bassoon's lowest B♭), two octaves below written middle C. At concert pitch this note is the B♭ below the second ledger line below the bass staff or B♭1 in scientific pitch notation. These three lowermost half-steps are played via additional keys operated by the right thumb, some of them often duplicated in the left- or right-hand little-finger key clusters. Overall, the instrument sounds an octave lower than the B♭ soprano clarinet.

As with all wind instruments, the upper limit of the range depends on the quality of the instrument and skill of the clarinetist. According to Aber and Lerstad, who give fingerings up to written C7 (sounding B♭5), the highest note commonly encountered in modern solo literature is the E below that (sounding D5, the D above treble C).[4] This gives the bass clarinet a usable range of up to four octaves, quite close to the range of the bassoon; indeed, many bass clarinetists perform works originally intended for bassoon or cello because of the plethora of literature for those two instruments and the scarcity of solo works for the bass clarinet.

Uses

The bass clarinet has been regularly used in scoring for orchestra and concert band since the mid-19th century, becoming more common during the middle and latter part of the 20th century. A bass clarinet is not always called for in orchestra music, but is almost always called for in concert band music. In recent years, the bass clarinet has also seen a growing repertoire of solo literature including compositions for the instrument alone, or accompanied by piano, orchestra, or other ensemble. It is also used in clarinet choirs, marching bands, and in film scoring, and has played a persistent role in jazz.

The bass clarinet has an appealing, rich, earthy tone quite distinct from other instruments in its range, drawing on and enhancing the qualities of the lower range of the soprano and alto instrument.

Musical compositions

Perhaps the earliest solo passages for bass clarinet—indeed, among the earliest parts for the instrument—occur in Mercadante's 1834 opera Emma d'Antiochia, in which a lengthy solo introduces Emma's scene in Act 2. (Mercadante actually specified a glicibarifono for this part.) Two years later, Giacomo Meyerbeer wrote an important solo for bass clarinet in Act 4 of his opera Les Huguenots.

French composer Hector Berlioz was one of the first of the Romantics to use the bass clarinet in his large-scale works such as the Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale, Op. 15 (1840), the Te Deum, Op. 22 (1849), and the opera Les Troyens, Op. 29 (1863). Later French composers to use the instrument included Maurice Ravel, who wrote virtuosic parts for the bass clarinet in his ballet Daphnis et Chloé (1912), La valse (1920), and his orchestration of Modest Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition (1924).

The operas of Richard Wagner also make extensive use of the bass clarinet, beginning with Tannhäuser (1845). He incorporated the instrument fully into the wind section as both a solo and supporting instrument. Wagner pioneered in exploiting the instrument's dark, somber tone to represent sadness and melancholy. Wagner was almost completely responsible for making the instrument a permanent member of the opera orchestra. The instrument plays an extensive role in Tristan und Isolde (1859), the operas of Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876), and Parsifal (1882).

Also around this time, Hungarian pianist and composer Franz Liszt wrote important parts for the instrument in his symphonic poems Ce qu'on entend sur la montagne (What One Hears on the Mountain), Tasso, and his Dante Symphony. Giuseppe Verdi followed suit, using it in Aida (1870), La forza del destino, Don Carlo and Falstaff. Following in Verdi's footsteps, Giacomo Puccini, composer of La Bohème, Tosca and Madame Butterfly, used the bass clarinet in all of his operas, beginning with Edgar in 1889. The Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky wrote some prominent solos for the instrument in his last ballet, The Nutcracker.

The later Romantics used the bass clarinet frequently in their works. All of Gustav Mahler's symphonies include the instrument prominently, and often contain lengthy solos for the instrument, especially in his Symphony No. 6 in A minor. Richard Strauss wrote for the instrument in all of his symphonic poems except for Don Juan, and the instrument shared the spotlight with the tenor tuba in his 1898 tone poem, Don Quixote, Op. 35. Strauss wrote for the instrument as he did for the smaller clarinets, and the parts often include playing in very high registers, such as in Also Sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30.

Composers of the Second Viennese School, Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern and Alban Berg, often favored the instrument over the bassoon, the instrument's closest relative in terms of range. Russian composers Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev used the low concert C and B♭ (equivalent to the bassoon's lowest two notes) in many of their compositions and an instrument with the extended range is necessary for works such as Shostakovich's Symphonies Nos. 4, 7, 8, and 11, and Leoš Janáček's Sinfonietta. All of these works exploit the instrument's dark, powerful lower range.

Prokofiev wrote parts for the instrument in his Symphonies Nos. 2–7 and in his ballet Romeo and Juliet. Sergei Rachmaninoff used the instrument to great effect in his Symphonies Nos. 2 and 3 and in his symphonic poem, Isle of The Dead. Igor Stravinsky also wrote complex parts for the instrument throughout his career, most prominently in his ballets The Firebird (1910), Petrushka (1911) and The Rite of Spring (1913).

The bass clarinet has a solo at the opening of the third movement of Ferde Grofé's Grand Canyon Suite.

In the duet "A Boy Like That" from West Side Story (1957), Leonard Bernstein scored for "the inky sounds of three bass clarinets".[5]

Early minimalist Steve Reich's Music for 18 Musicians (1976) calls for two bass clarinets, featured prominently in the lower register. Used almost percussively, the effect of deep, staccato repetitions, played beneath a static rhythmic drone, is to create a feeling of slowly fluctuating cycles.

Many modern composers employ the bass along with the contra-alto and contrabass clarinets, such as Esa-Pekka Salonen in his Piano Concerto. A great amount of literature can be found in the wind ensemble, in which there is always a part for the instrument.

There are a few major solo pieces for bass clarinet, including:

- Kalevi Aho Concerto for Bass Clarinet and Orchestra (2018)

- Ann Callaway Concerto for Bass Clarinet and Chamber Orchestra (1985–87) (Subito Music)

- Anders Eliasson Concerto for Bass Clarinet and Orchestra (1996)

- Peter Maxwell Davies: The Seas of Kirk Swarf for bass clarinet and strings (2007).[6]

- Osvaldo Golijov: Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind for Klezmer clarinetist (soprano clarinets, bass clarinet and/or basset horn) and string quartet, later arranged for solo clarinetist and string orchestra.

- Rafael Leonardo Junchaya: Concerto Silvestre for bass clarinet and orchestra Op.14a. Premiered by Marco Antonio Mazzini and the GUSO Orchestra conducted by Steven Decraene in May 2009. First version for bass clarinet and string orchestra (Concertino Silvestre Op.14) premiered in Guatemala in July 2009.

- Jos Kunst (composer): Solo identity I (1972)

- David Lang: Press Release for solo bass clarinet (1991) (For Evan Ziporyn)

- Donald Martino: Triple Concerto for clarinet, bass clarinet, and contrabass clarinet.

- Thea Musgrave: Concerto for bass clarinet and orchestra.

- Jonathan Russell:

- Bass clarinet concerto (2014)

- Double bass-clarinet concerto.

- Karlheinz Stockhausen:

- In Freundschaft for unaccompanied bass clarinet,

- Libra for bass clarinet and electronic music (a separable component of Sirius)

- Harmonien for unaccompanied bass clarinet.

- Benjamin Staern: Worried Souls: concerto for clarinet/bass clarinet and symphony orchestra (2012).

There is a limited chamber repertoire for bass clarinet and other instruments, notably Leoš Janáček's suite Mládí (Youth), and Karlheinz Stockhausen's Kontra-Punkte.

Soloists and ensembles

It was not until the 1950s that classical performers began to adopt the bass clarinet as their primary instrument. The pioneer was the Czech performer Josef Horák (1931–2005), who is credited as having performed the first ever solo bass clarinet recital on March 23, 1955.[7] This marked a turning point when the instrument first became thought of as a soloist's instrument.

Because the repertoire of solo music for the bass clarinet was quite small, most bass clarinet soloists specialize in new music, while also arranging works composed for other instruments from earlier eras (such as the Bach Cello Suites). Beginning with Horák, many players have commissioned works for the instrument, and consequently there now exists a repertoire of hundreds of solo works, many by prominent international composers such as Brian Ferneyhough and David Lang. In addition to Horák, other specialist performers include Henri Bok (Netherlands), his student Luís Afonso (Brazil), Dennis Smylie (United States), Tommie Lundberg (Sweden), Harry Sparnaay (Netherlands, who has worked with important composers such as Luciano Berio, Iannis Xenakis, and Morton Feldman), Jason Alder, Evan Ziporyn (United States), and Michael Lowenstern (United States); the latter two are also composers.

In October 2005, the First World Bass Clarinet Convention was held in Rotterdam, Netherlands, at which Horák was the guest of honor and played in one of the many concerts given by the leading bass clarinetists from around the world (including all the aforementioned performers, as well as many others).[8]

At least two professional bass-clarinet quartets exist. Rocco Parisi's Bass Clarinet Quartet is an Italian group whose repertoire includes transcriptions of music by Rossini, Paganini, and Piazzolla. Edmund Welles is the name of a bass clarinet quartet based in San Francisco. Their repertoire includes original "heavy chamber music" and transcriptions of madrigals, boogie-woogie tunes, and heavy metal songs. Two of the members of Edmund Welles also perform as a bass clarinet duo, Sqwonk.[9]

In jazz

While the bass clarinet was seldom heard in early jazz compositions, a bass clarinet solo by Wilbur Sweatman can be heard on his 1924 recording "Battleship Kate" and a bass clarinet solo by Omer Simeon can be heard in the 1926 recording "Someday Sweetheart" by Jelly Roll Morton and His Red Hot Peppers. Additionally, Benny Goodman recorded with the instrument a few times early in his career.

Harry Carney, Duke Ellington's baritone saxophonist for 47 years, played bass clarinet in some of Ellington's arrangements, first recording with it on "Saddest Tale" in 1934. He was featured soloist on many Ellington recordings, including 27 titles on bass clarinet.[10]

The first jazz album on which the leader solely played bass clarinet was Great Ideas of Western Mann (1957) by Herbie Mann, better known as a flautist. However, avant-garde musician Eric Dolphy (1928–1964) was the first major jazz soloist on the instrument, and established much of the vocabulary and technique used by later performers. He used the entire range of the instrument in his solos. Bennie Maupin emerged in the late 1960s as a primary player of the instrument, playing on Miles Davis's seminal record Bitches Brew as well as several records with Herbie Hancock's Mwandishi group. His style resembles Dolphy's in its use of advanced harmonies.

While the bass clarinet has been used often since Dolphy, it is typically used by a saxophonist or clarinetist as a second or third instrument; such musicians include David Murray, Marcus Miller, John Surman, John Gilmore, Bob Mintzer, John Coltrane (to whom Dolphy's mother left some of Dolphy's instruments including his bass clarinet), Brian Landrus, James Carter, Steve Buckley, Andy Biskin, Don Byron, Julian Siegel, Gunter Hampel, Michel Portal, Myron Walden, and Chris Potter. Very few performers have used the instrument exclusively, but such performers include Berlin-based bass clarinetist Rudi Mahall, and French bass clarinetists Louis Sclavis and Denis Colin. Klezmer clarinetist Giora Feidman is known for idiosyncratic use of the bass clarinet on some klezmer and jazz tunes.

History

There are several instruments that can arguably be considered the first bass clarinet. Probably the earliest is a dulcian-shaped instrument in the Museum Carolino Augusteum in Salzburg. It is incomplete, lacking a crook or mouthpiece, and appears to date from the first half of the eighteenth century. Its wide cylindrical bore and its fingering suggest it was a chalumeau or clarinet in the bass range.[11] Four anonymous bass chalumeaux or clarinets apparently dating from the eighteenth century and having from one to six keys also appear to be among the earliest examples, and one in particular has been suggested to date from before 1750.[12] However, the authenticity of at least one of these instruments has been questioned.[13]

In the Munich Stadtmuseum there is an instrument made c. 1770 by the Mayrhofers of Passau,[13] who are often credited with the invention of the basset horn. It resembles early sickle-shaped basset horns, but has a larger bore and is longer, playing in low B♭. Whether this should be considered a low basset horn or a bass clarinet is a matter of opinion. In any case, no further work along this line is known to have been done.

A 1772 newspaper article describes an instrument called the "basse-tube," invented by G. Lott in Paris in 1772.[14] This instrument has not survived and very little is known of it. The article has frequently been cited as the earliest record of a bass clarinet, but it has more recently been suggested that the basse-tube was in fact a basset horn.[15]

The Klarinetten-Bass by Heinrich Grenser, c. 1793, had a folded, bassoon-like shape and an extended range, and was presumably intended to serve as a bassoon replacement in military bands. Desfontenelles of Lisieux built a bass clarinet in 1807 whose shape was similar to that of the later saxophone. It had thirteen keys, at a time when most soprano clarinets had fewer.

Additional designs were developed by many other makers, including Dumas of Sommières (who called his instrument a "Basse guerrière") in 1807; Nicola Papalini, c. 1810 (an odd design, in the form of a serpentine series of curves, carved out of wood); George Catlin of Hartford, Connecticut ("clarion") c. 1810; Sautermeister of Lyons ("Basse-orgue") in 1812; Gottlieb Streitwolf in 1828; and Catterino Catterini ("glicibarifono") in the 1830s.[11][12][16] These last four, and several others of the same period, had bassoon-like folded shapes, and most had extended ranges. A straight-bodied instrument without extended range was produced in 1832 by Isaac Dacosta and Auguste Buffet.[11][12]

Finally, Adolphe Sax, a Belgian manufacturer of musical instruments, designed a straight-bodied form of the bass clarinet in 1838. Sax's expertise in acoustics led him to include such features as accurately-placed, large tone holes and a second register hole. His instrument achieved great success and became the basis for all bass clarinet designs since.

The instrument on which Anton Stadler first played Mozart's clarinet concerto was originally called a Bass-Klarinette, but was not a bass clarinet in the modern sense; since the late eighteenth century this instrument has been called a basset clarinet.

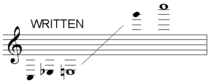

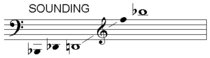

Notation

Orchestral music for bass clarinet is written using one of four systems:

- Conventional treble clef in B♭ (French notation). This sounds an octave and a major second lower than written and therefore uses the same fingerings as the soprano clarinet, and is the most common.

- Bass clef in B♭ (German notation). This sounds a major second (tone, or whole step) lower than written.[lower-alpha 1] For music written in bass clef, higher passages may be written in treble clef to avoid the use of excessive ledger lines, but this should not be confused with system (a), in which notes sound an octave lower than in system (b). It is therefore necessary to play the treble clef one octave higher than it would be played in French notation, so that it continues to sound a major second lower. Unlike music for the bassoon, the tenor clef is not used for higher passages.

- Bass clef in B♭ (Russian notation). This notation mixes the German and French systems. Music written in bass clef is played a major second lower than written (German), however when written in treble clef, it sounds a major ninth lower, so the player uses the fingerings they normally would when playing soprano clarinet (French). [lower-alpha 2]

- Bass clef in B♭ (Italian notation). This notation is written a major ninth higher than sounding pitch, as the French notation, however also uses bass clef. This means that the bass clef part would be read an octave lower than if reading it in German notation. The treble clef remains the same as French notation. [lower-alpha 3]

Music is occasionally encountered written for the bass clarinet in A, e.g. in Wagner operas, and Mahler or Rachmaninov symphonies; this music also tends to be written in bass clef although not invariably (e.g. Ravel's La Valse). Apparently, bass clarinets in A were once produced by German and French makers, even though the historic record is not particularly clear just where and when such production started and ceased. Since instruments pitched in A were not available to play music that had already been written, bass clarinets produced after 1900 were equipped with the low E♭ extension key to allow easy transposition of such parts.

Until the last half of the 20th century, no new bass clarinets pitched in A were produced. For a brief period starting in the late 1970s, a bass clarinet with Boehm style keywork and pitched in A (and keyed to low E♭, even though the original parts seldom descend below written low E) was again produced by Selmer Paris. While perfectly functional, such instruments were both expensive and a significant physical burden to the player, who would have to carry two heavy bass clarinets to rehearsals and performances. For these two reasons more than anything else, few modern bass clarinets in A have been sold. At some point after the 1980s, Selmer ceased production of the bass clarinet in A, although examples are still available from factory stock.

Very few modern players own a bass clarinet in A; these parts are therefore played on the B♭ instrument, transposing them down a semitone.

Notes

- An example of this notation is in Paul Dukas's symphonic poem "The Sorcerer's Apprentice".

- An example of this notation is in Igor Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring".

- An example of this notation is in Luigi Nono's "Canti per 13".

References

- Sadie, Stanley, ed. (1984). "Clarinet". The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. London: Macmillan.

- "Clarinetist". The Free Dictionary. Farlex, Inc. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- "Moennig metal bass clarinet". Bass Clarinet A Go Go!. March 1, 2008. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- Aber, Thomas; Lerstad, Terje. "Altissimo Fingerings". Kunst.no. Archived from the original on 2006-08-28. Retrieved 2006-10-01.

- Simeone, Nigel (2009). Leonard Bernstein, West Side Story. Landmarks in Music Since 1950. Farnham, Surrey, and Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 110. ISBN 9780754664840.

- Bruce, Keith (June 20, 2007). "The Saint and the Shebeen". The Herald. Archived from the original on 2007-06-29. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- Kovárnová, Emma (December 2014). "Josef Horák – Pioneer of the Bass Clarinet". The Clarinet. 41 (4): 44. ISSN 0361-5553.

- Mestrom, Maarten (March 2005). "The First World Bass Clarinet Convention in Rotterdam 2005". The Clarinet. 32 (2): 56–57. ISSN 0361-5553.

- "Sqwonk – Bass Clarinet Duo". Sqwonk.com. Archived from the original on 2018-03-23. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- Massagli, Luciano; Volonté, Giovanni M. (1999). The New Desor, An updated edition of Duke Ellington's Story on Records, 1924–1974. Milan. p. 350.

- van der Meer, John Henry (1987). "The Typology and History of the Bass Clarinet". J. Amer. Mus. Inst. Soc. 13: 65–88.

- Rendall, F. Geoffrey (1957). The Clarinet (Second Revised ed.). London: Ernest Benn Limited.

- Young, Phillip T. (1981). "A Bass Clarinet by the Mayrhofers of Passau". J. Amer. Mus. Inst. Soc. 7: 36–46.

- Sachs, Curt (1940). A History of Musical Instruments. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Rice, Albert R. (2009). From the Clarinet d'Amour to the Contra Bass: A History of Large Size Clarinets, 1740–1860. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199711178.

- Eliason, Robert E. (1983). "George Catlin, Hartford Musical Instrument Maker (Part 2)". Journal of the American Musical Instrument Society. 9: 21–52.

Further reading

- Mazzini, Marco A. (April 2, 2005). "Harry Sparnaay". Clariperu (interview) (in Spanish).

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bass Clarinet. |