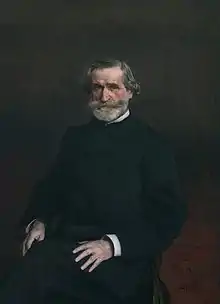

Giuseppe Verdi

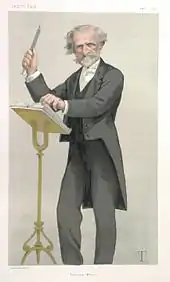

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (Italian: [dʒuˈzɛppe ˈverdi]; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian opera composer. He was born near Busseto to a provincial family of moderate means, and developed a musical education with the help of a local patron. Verdi came to dominate the Italian opera scene after the era of Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti, and Gioachino Rossini, whose works significantly influenced him.

In his early operas, Verdi demonstrated a sympathy with the Risorgimento movement which sought the unification of Italy. He also participated briefly as an elected politician. The chorus "Va, pensiero" from his early opera Nabucco (1842), and similar choruses in later operas, were much in the spirit of the unification movement, and the composer himself became esteemed as a representative of these ideals. An intensely private person, Verdi, however, did not seek to ingratiate himself with popular movements and as he became professionally successful was able to reduce his operatic workload and sought to establish himself as a landowner in his native region. He surprised the musical world by returning, after his success with the opera Aida (1871), with three late masterpieces: his Requiem (1874), and the operas Otello (1887) and Falstaff (1893).

His operas remain extremely popular, especially the three peaks of his 'middle period': Rigoletto, Il trovatore and La traviata, and the 2013 bicentenary of his birth was widely celebrated in broadcasts and performances.

Life

Childhood and education

Verdi, the first child of Carlo Giuseppe Verdi (1785–1867) and Luigia Uttini (1787–1851), was born at their home in Le Roncole, a village near Busseto, then in the Département Taro and within the borders of the First French Empire following the annexation of the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza in 1808. The baptismal register, prepared on 11 October 1813, lists his parents Carlo and Luigia as "innkeeper" and "spinner" respectively. Additionally, it lists Verdi as being "born yesterday", but since days were often considered to begin at sunset, this could have meant either 9 or 10 October.[1] Following his mother, Verdi always celebrated his birthday on 9 October, the day he himself believed he was born.[2]

Verdi had a younger sister, Giuseppa, who died aged 17 in 1833.[2] She is said to have been his closest friend during childhood.[3] From the age of four, Verdi was given private lessons in Latin and Italian by the village schoolmaster, Baistrocchi, and at six he attended the local school. After learning to play the organ, he showed so much interest in music that his parents finally provided him with a spinet.[4] Verdi's gift for music was already apparent by 1820–21 when he began his association with the local church, serving in the choir, acting as an altar boy for a while, and taking organ lessons. After Baistrocchi's death, Verdi, at the age of eight, became the official paid organist.[5]

The music historian Roger Parker points out that both of Verdi's parents "belonged to families of small landowners and traders, certainly not the illiterate peasants from which Verdi later liked to present himself as having emerged... Carlo Verdi was energetic in furthering his son's education...something which Verdi tended to hide in later life... [T]he picture emerges of youthful precocity eagerly nurtured by an ambitious father and of a sustained, sophisticated and elaborate formal education."[6]

In 1823, when he was 10, Verdi's parents arranged for the boy to attend school in Busseto, enrolling him in a Ginnasio—an upper school for boys—run by Don Pietro Seletti, while they continued to run their inn at Le Roncole. Verdi returned to Busseto regularly to play the organ on Sundays, covering the distance of several kilometres on foot.[7] At age 11, Verdi received schooling in Italian, Latin, the humanities, and rhetoric. By the time he was 12, he began lessons with Ferdinando Provesi, maestro di cappella at San Bartolomeo, director of the municipal music school and co-director of the local Società Filarmonica (Philharmonic Society). Verdi later stated: "From the ages of 13 to 18 I wrote a motley assortment of pieces: marches for band by the hundred, perhaps as many little sinfonie that were used in church, in the theatre and at concerts, five or six concertos and sets of variations for pianoforte, which I played myself at concerts, many serenades, cantatas (arias, duets, very many trios) and various pieces of church music, of which I remember only a Stabat Mater."[1] This information comes from the Autobiographical Sketch which Verdi dictated to the publisher Giulio Ricordi late in life, in 1879, and remains the leading source for his early life and career.[8] Written, understandably, with the benefit of hindsight, it is not always reliable when dealing with issues more contentious than those of his childhood.[9][10]

The other director of the Philharmonic Society was Antonio Barezzi, a wholesale grocer and distiller, who was described by a contemporary as a "manic dilettante" of music. The young Verdi did not immediately become involved with the Philharmonic. By June 1827, he had graduated with honours from the Ginnasio and was able to focus solely on music under Provesi. By chance, when he was 13, Verdi was asked to step in as a replacement to play in what became his first public event in his home town; he was an immediate success mostly playing his own music to the surprise of many and receiving strong local recognition.[11]

By 1829–30, Verdi had established himself as a leader of the Philharmonic: "none of us could rival him" reported the secretary of the organisation, Giuseppe Demaldè. An eight-movement cantata, I deliri di Saul, based on a drama by Vittorio Alfieri, was written by Verdi when he was 15 and performed in Bergamo. It was acclaimed by both Demaldè and Barezzi, who commented: "He shows a vivid imagination, a philosophical outlook, and sound judgment in the arrangement of instrumental parts."[12] In late 1829, Verdi had completed his studies with Provesi, who declared that he had no more to teach him.[13] At the time, Verdi had been giving singing and piano lessons to Barezzi's daughter Margherita; by 1831, they were unofficially engaged.[1]

Verdi set his sights on Milan, then the cultural capital of northern Italy, where he applied unsuccessfully to study at the Conservatory.[1] Barezzi made arrangements for him to become a private pupil of Vincenzo Lavigna, who had been maestro concertatore at La Scala, and who described Verdi's compositions as "very promising".[14] Lavigna encouraged Verdi to take out a subscription to La Scala, where he heard Maria Malibran in operas by Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini.[15] Verdi began making connections in the Milanese world of music that were to stand him in good stead. These included an introduction by Lavigna to an amateur choral group, the Società Filarmonica, led by Pietro Massini.[16] Attending the Società frequently in 1834, Verdi soon found himself functioning as rehearsal director (for Rossini's La cenerentola) and continuo player. It was Massini who encouraged him to write his first opera, originally titled Rocester, to a libretto by the journalist Antonio Piazza.[1]

1834–1842: First operas

List of compositions by Giuseppe Verdi

In mid-1834, Verdi sought to acquire Provesi's former post in Busseto but without success. But with Barezzi's help he did obtain the secular post of maestro di musica. He taught, gave lessons, and conducted the Philharmonic for several months before returning to Milan in early 1835.[6] By the following July, he obtained his certification from Lavigna.[17] Eventually in 1835 Verdi became director of the Busseto school with a three-year contract. He married Margherita in May 1836, and by March 1837, she had given birth to their first child, Virginia Maria Luigia on 26 March 1837. Icilio Romano followed on 11 July 1838. Both the children died young, Virginia on 12 August 1838, Icilio on 22 October 1839.[1]

In 1837, the young composer asked for Massini's assistance to stage his opera in Milan.[18] The La Scala impresario, Bartolomeo Merelli, agreed to put on Oberto (as the reworked opera was now called, with a libretto rewritten by Temistocle Solera)[19] in November 1839. It achieved a respectable 13 additional performances, following which Merelli offered Verdi a contract for three more works.[20]

While Verdi was working on his second opera Un giorno di regno, Margherita died of encephalitis at the age of 26. Verdi adored his wife and children and was devastated by their deaths. Un giorno, a comedy, was premiered only a few months later. It was a flop and only given the one performance.[20] Following its failure, it is claimed Verdi vowed never to compose again,[10] but in his Sketch he recounts how Merelli persuaded him to write a new opera.

Verdi was to claim that he gradually began to work on the music for Nabucco, the libretto of which had originally been rejected by the composer Otto Nicolai:[21] "This verse today, tomorrow that, here a note, there a whole phrase, and little by little the opera was written", he later recalled.[22] By the autumn of 1841 it was complete, originally under the title Nabucodonosor. Well received at its first performance on 9 March 1842, Nabucco underpinned Verdi's success until his retirement from the theatre, twenty-nine operas (including some revised and updated versions) later.[10] At its revival in La Scala for the 1842 autumn season it was given an unprecedented (and later unequalled) total of 57 performances; within three years it had reached (among other venues) Vienna, Lisbon, Barcelona, Berlin, Paris and Hamburg; in 1848 it was heard in New York, in 1850 in Buenos Aires. Porter comments that "similar accounts...could be provided to show how widely and rapidly all [Verdi's] other successful operas were disseminated."[23]

1842–1849

A period of hard work for Verdi—with the creation of twenty operas (excluding revisions and translations)—followed over the next sixteen years, culminating in Un ballo in maschera. This period was not without its frustrations and setbacks for the young composer, and he was frequently demoralised. In April 1845, in connection with I due Foscari, he wrote: "I am happy, no matter what reception it gets, and I am utterly indifferent to everything. I cannot wait for these next three years to pass. I have to write six operas, then addio to everything."[24] In 1858 Verdi complained: "Since Nabucco, you may say, I have never had one hour of peace. Sixteen years in the galleys."[25]

After the initial success of Nabucco, Verdi settled in Milan, making a number of influential acquaintances. He attended the Salotto Maffei, Countess Clara Maffei's salons in Milan, becoming her lifelong friend and correspondent.[10] A revival of Nabucco followed in 1842 at La Scala where it received a run of fifty-seven performances,[26] and this led to a commission from Merelli for a new opera for the 1843 season. I Lombardi alla prima crociata was based on a libretto by Solera and premiered in February 1843. Inevitably, comparisons were made with Nabucco; but one contemporary writer noted: "If [Nabucco] created this young man's reputation, I Lombardi served to confirm it."[27]

Verdi paid close attention to his financial contracts, making sure he was appropriately remunerated as his popularity increased. For I Lombardi and Ernani (1844) in Venice he was paid 12,000 lire (including supervision of the productions); Attila and Macbeth (1847), each brought him 18,000 lire. His contracts with the publishers Ricordi in 1847 were very specific about the amounts he was to receive for new works, first productions, musical arrangements, and so on.[28] He began to use his growing prosperity to invest in land near his birthplace. In 1844 he purchased Il Pulgaro, 62 acres (23 hectares) of farmland with a farmhouse and outbuildings, providing a home for his parents from May 1844. Later that year, he also bought the Palazzo Cavalli (now known as the Palazzo Orlandi) on the via Roma, Busseto's main street.[29] In May 1848, Verdi signed a contract for land and houses at Sant'Agata in Busseto, which had once belonged to his family.[30] It was here he built his own house, completed in 1880, now known as the Villa Verdi, where he lived from 1851 until his death.[31]

In March 1843, Verdi visited Vienna (where Gaetano Donizetti was musical director) to oversee a production of Nabucco. The older composer, recognising Verdi's talent, noted in a letter of January 1844: "I am very, very happy to give way to people of talent like Verdi... Nothing will prevent the good Verdi from soon reaching one of the most honourable positions in the cohort of composers."[32] Verdi travelled on to Parma, where the Teatro Regio di Parma was producing Nabucco with Strepponi in the cast. For Verdi the performances were a personal triumph in his native region, especially as his father, Carlo, attended the first performance. Verdi remained in Parma for some weeks beyond his intended departure date. This fuelled speculation that the delay was due to Verdi's interest in Giuseppina Strepponi (who stated that their relationship began in 1843).[33] Strepponi was in fact known for her amorous relationships (and many illegitimate children) and her history was an awkward factor in their relationship until they eventually agreed on marriage.[34]

After successful stagings of Nabucco in Venice (with twenty-five performances in the 1842/43 season), Verdi began negotiations with the impresario of La Fenice to stage I Lombardi, and to write a new opera. Eventually, Victor Hugo's Hernani was chosen, with Francesco Maria Piave as librettist. Ernani was successfully premiered in 1844 and within six months had been performed at twenty other theatres in Italy, and also in Vienna.[35] The writer Andrew Porter notes that for the next ten years, Verdi's life "reads like a travel diary—a timetable of visits...to bring new operas to the stage or to supervise local premieres". La Scala premiered none of these new works, except for Giovanna d'Arco. Verdi "never forgave the Milanese for their reception of Un giorno di regno".[28]

During this period, Verdi began to work more consistently with his librettists. He relied on Piave again for I due Foscari, performed in Rome in November 1844, then on Solera once more for Giovanna d'Arco, at La Scala in February 1845, while in August that year he was able to work with Salvadore Cammarano on Alzira for the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples. Solera and Piave worked together on Attila for La Fenice (March 1846).[36]

In April 1844, Verdi took on Emanuele Muzio, eight years his junior, as a pupil and amanuensis. He had known him since about 1828 as another of Barezzi's protégés.[37] Muzio, who in fact was Verdi's only pupil, became indispensable to the composer. He reported to Barezzi that Verdi "has a breadth of spirit, of generosity, a wisdom".[38] In November 1846, Muzio wrote of Verdi: "If you could see us, I seem more like a friend, rather than his pupil. We are always together at dinner, in the cafes, when we play cards...; all in all, he doesn't go anywhere without me at his side; in the house we have a big table and we both write there together, and so I always have his advice."[39] Muzio was to remain associated with Verdi, assisting in the preparation of scores and transcriptions, and later conducting many of his works in their premiere performances in the US and elsewhere outside Italy. He was chosen by Verdi as one of the executors of his will, but predeceased the composer in 1890.[40]

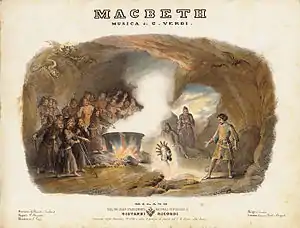

After a period of illness Verdi began work on Macbeth in September 1846. He dedicated the opera to Barezzi: "I have long intended to dedicate an opera to you, as you have been a father, a benefactor and a friend for me. It was a duty I should have fulfilled sooner if imperious circumstances had not prevented me. Now, I send you Macbeth, which I prize above all my other operas, and therefore deem worthier to present to you."[41] In 1997 Martin Chusid wrote that Macbeth was the only one of Verdi's operas of his "early period" to remain regularly in the international repertoire,[42] although in the 21st century Nabucco has also entered the lists.[43]

Strepponi's voice declined and her engagements dried up in the 1845 to 1846 period, and she returned to live in Milan whilst retaining contact with Verdi as his "supporter, promoter, unofficial adviser, and occasional secretary" until she decided to move to Paris in October 1846. Before she left Verdi gave her a letter that pledged his love. On the envelope, Strepponi wrote: "5 or 6 October 1846. They shall lay this letter on my heart when they bury me."[44]

Verdi had completed I masnadieri for London by May 1847 except for the orchestration. This he left until the opera was in rehearsal, since he wanted to hear "la [Jenny] Lind and modify her role to suit her more exactly".[45] Verdi agreed to conduct the premiere on 22 July 1847 at Her Majesty's Theatre, as well as the second performance. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert attended the first performance, and for the most part, the press was generous in its praise.[46]

For the next two years, except for two visits to Italy during periods of political unrest, Verdi was based in Paris.[47] Within a week of returning to Paris in July 1847, he received his first commission from the Paris Opéra. Verdi agreed to adapt I Lombardi to a new French libretto; the result was Jérusalem, which contained significant changes to the music and structure of the work (including an extensive ballet scene) to meet Parisian expectations.[48] Verdi was awarded the Order of Chevalier of the Legion of Honour.[49][n 1] To satisfy his contracts with the publisher Francesco Lucca, Verdi dashed off Il Corsaro. Budden comments "In no other opera of his does Verdi appear to have taken so little interest before it was staged."[52]

On hearing the news of the "Cinque Giornate", the "Five Days" of street fighting that took place between 18 and 22 March 1848 and temporarily drove the Austrians out of Milan, Verdi travelled there, arriving on 5 April.[53] He discovered that Piave was now "Citizen Piave" of the newly proclaimed Republic of San Marco. Writing a patriotic letter to him in Venice, Verdi concluded "Banish every petty municipal idea! We must all extend a fraternal hand, and Italy will yet become the first nation of the world...I am drunk with joy! Imagine that there are no more Germans here!!"[54]

Verdi had been admonished by the poet Giuseppe Giusti for turning away from patriotic subjects, the poet pleading with him to "do what you can to nourish the [sorrow of the Italian people], to strengthen it, and direct it to its goal."[55] Cammarano suggested adapting Joseph Méry's 1828 play La Bataille de Toulouse, which he described as a story "that should stir every man with an Italian soul in his breast".[56] The premiere was set for late January 1849. Verdi travelled to Rome before the end of 1848. He found that city on the verge of becoming a (short-lived) republic, which commenced within days of La battaglia di Legnano's enthusiastically received premiere. In the spirit of the time were the tenor hero's final words, "Whoever dies for the fatherland cannot be evil-minded".[57]

Verdi had intended to return to Italy in early 1848, but was prevented by work and illness, as well as, most probably, by his increasing attachment to Strepponi. Verdi and Strepponi left Paris in July 1849, the immediate cause being an outbreak of cholera,[58] and Verdi went directly to Busseto to continue work on completing his latest opera, Luisa Miller, for a production in Naples later in the year.[59]

1849–1853: Fame

Verdi was committed to the publisher Giovanni Ricordi for an opera—which became Stiffelio—for Trieste in the Spring of 1850; and, subsequently, following negotiations with La Fenice, developed a libretto with Piave and wrote the music for Rigoletto (based on Victor Hugo's Le roi s'amuse) for Venice in March 1851. This was the first of a sequence of three operas (followed by Il trovatore and La traviata) which were to cement his fame as a master of opera.[60] The failure of Stiffelio (attributable not least to the censors of the time taking offence at the taboo subject of the supposed adultery of a clergyman's wife and interfering with the text and roles) incited Verdi to take pains to rework it, although even in the completely recycled version of Aroldo (1857) it still failed to please.[61] Rigoletto, with its intended murder of royalty, and its sordid attributes, also upset the censors. Verdi would not compromise:

What does the sack matter to the police? Are they worried about the effect it will produce?...Do they think they know better than I?...I see the hero has been made no longer ugly and hunchbacked!! Why? A singing hunchback...why not?...I think it splendid to show this character as outwardly deformed and ridiculous, and inwardly passionate and full of love. I chose the subject for these very qualities...if they are removed I can no longer set it to music.[62]

Verdi substituted a Duke for the King, and the public response and subsequent success of the opera all over Italy and Europe fully vindicated the composer.[63] Aware that the melody of the Duke's song "La donna è mobile" ("Woman is fickle") would become a popular hit, Verdi excluded it from orchestral rehearsals for the opera, and rehearsed the tenor separately.[64][n 2]

For several months Verdi was preoccupied with family matters. These stemmed from the way in which the citizens of Busseto were treating Giuseppina Strepponi, with whom he was living openly in an unmarried relationship. She was shunned in the town and at church, and while Verdi appeared indifferent, she was certainly not.[66] Furthermore, Verdi was concerned about the administration of his newly acquired property at Sant'Agata.[67] A growing estrangement between Verdi and his parents was perhaps also attributable to Strepponi[68] (the suggestion that this situation was sparked by the birth of a child to Verdi and Strepponi which was given away as a foundling[69] lacks any firm evidence). In January 1851, Verdi broke off relations with his parents, and in April they were ordered to leave Sant'Agata; Verdi found new premises for them and helped them financially to settle into their new home. It may not be coincidental that all six Verdi operas written in the period 1849–53 (La battaglia, Luisa Miller, Stiffelio, Rigoletto, Il trovatore and La traviata), have, uniquely in his oeuvre, heroines who are, in the opera critic Joseph Kerman's words, "women who come to grief because of sexual transgression, actual or perceived". Kerman, like the psychologist Gerald Mendelssohn, sees this choice of subjects as being influenced by Verdi's uneasy passion for Strepponi.[70]

Verdi and Strepponi moved into Sant'Agata on 1 May 1851.[71] May also brought an offer for a new opera from La Fenice, which Verdi eventually realised as La traviata. That was followed by an agreement with the Rome Opera company to present Il trovatore for January 1853.[72] Verdi now had sufficient earnings to retire, had he wished to.[73] He had reached a stage where he could develop his operas as he wished, rather than be dependent on commissions from third parties. Il trovatore was in fact the first opera he wrote without a specific commission (apart from Oberto).[74] At around the same time he began to consider creating an opera from Shakespeare's King Lear. After first (1850) seeking a libretto from Cammarano (which never appeared), Verdi later (1857) commissioned one from Antonio Somma, but this proved intractable, and no music was ever written.[75][n 3] Verdi began work on Il trovatore after the death of his mother in June 1851. The fact that this is "the one opera of Verdi's which focuses on a mother rather than a father" is perhaps related to her death.[78]

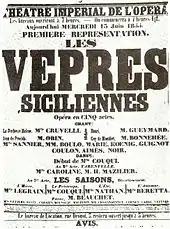

In the winter of 1851–52 Verdi decided to go to Paris with Strepponi, where he concluded an agreement with the Opéra to write what became Les vêpres siciliennes, his first original work in the style of grand opera. In February 1852, the couple attended a performance of Alexander Dumas fils's play The Lady of the Camellias; Verdi immediately began to compose music for what would later become La traviata.[79]

After his visit to Rome for Il trovatore in January 1853, Verdi worked on completing La traviata, but with little hope of its success, due to his lack of confidence in any of the singers engaged for the season.[80] Furthermore, the management insisted that the opera be given a historical, not a contemporary setting. The premiere in March 1853 was indeed a failure: Verdi wrote: "Was the fault mine or the singers'? Time will tell."[81] Subsequent productions (following some rewriting) throughout Europe over the following two years fully vindicated the composer; Roger Parker has written "Il trovatore consistently remains one of the three or four most popular operas in the Verdian repertoire: but it has never pleased the critics".[82]

1853–1860: Consolidation

In the eleven years up to and including Traviata, Verdi had written sixteen operas. Over the next eighteen years (up to Aida), he wrote only six new works for the stage.[83] Verdi was happy to return to Sant'Agata and, in February 1856, was reporting a "total abandonment of music; a little reading; some light occupation with agriculture and horses; that's all". A couple of months later, writing in the same vein to Countess Maffei he stated: "I'm not doing anything. I don't read. I don't write. I walk in the fields from morning to evening, trying to recover, so far without success, from the stomach trouble caused me by I vespri siciliani. Cursed operas!"[84] An 1858 letter by Strepponi to the publisher Léon Escudier describes the kind of lifestyle that increasingly appealed to the composer: "His love for the country has become a mania, madness, rage, and fury—anything you like that is exaggerated. He gets up almost with the dawn, to go and examine the wheat, the maize, the vines, etc....Fortunately our tastes for this sort of life coincide, except in the matter of sunrise, which he likes to see up and dressed, and I from my bed."[85]

Nonetheless on 15 May, Verdi signed a contract with La Fenice for an opera for the following spring. This was to be Simon Boccanegra. The couple stayed in Paris until January 1857 to deal with these proposals, and also the offer to stage the translated version of Il trovatore as a grand opera. Verdi and Strepponi travelled to Venice in March for the premiere of Simon Boccanegra, which turned out to be "a fiasco" (as Verdi reported, although on the second and third nights, the reception improved considerably).[86]

With Strepponi, Verdi went to Naples early in January 1858 to work with Somma on the libretto of the opera Gustave III, which over a year later would become Un ballo in maschera. By this time, Verdi had begun to write about Strepponi as "my wife" and she was signing her letters as "Giuseppina Verdi".[85] Verdi raged against the stringent requirements of the Neapolitan censor stating: "I'm drowning in a sea of troubles. It's almost certain that the censors will forbid our libretto."[87] With no hope of seeing his Gustavo III staged as written, he broke his contract. This resulted in litigation and counter-litigation; with the legal issues resolved, Verdi was free to present the libretto and musical outline of Gustave III to the Rome Opera. There, the censors demanded further changes; at this point, the opera took the title Un ballo in maschera.[88]

Arriving in Sant'Agata in March 1859 Verdi and Strepponi found the nearby city of Piacenza occupied by about 6,000 Austrian troops who had made it their base, to combat the rise of Italian interest in unification in the Piedmont region. In the ensuing Second Italian War of Independence the Austrians abandoned the region and began to leave Lombardy, although they remained in control of the Venice region under the terms of the armistice signed at Villafranca. Verdi was disgusted at this outcome: "[W]here then is the independence of Italy, so long hoped for and promised?...Venice is not Italian? After so many victories, what an outcome... It is enough to drive one mad" he wrote to Clara Maffei.[89]

Verdi and Strepponi now decided on marriage; they travelled to Collonges-sous-Salève, a village then part of Piedmont. On 29 August 1859 the couple were married there, with only the coachman who had driven them there and the church bell-ringer as witnesses.[90] At the end of 1859, Verdi wrote to his friend Cesare De Sanctis "[Since completing Ballo] I have not made any more music, I have not seen any more music, I have not thought anymore about music. I don't even know what colour my last opera is, and I almost don't remember it." [91] He began to remodel Sant'Agata, which took most of 1860 to complete and on which he continued to work for the next twenty years. This included major work on a square room that became his workroom, his bedroom, and his office.[92]

Politics

Having achieved some fame and prosperity, Verdi began in 1859 to take an active interest in Italian politics. His early commitment to the Risorgimento movement is difficult to estimate accurately; in the words of the music historian Philip Gossett "myths intensifying and exaggerating [such] sentiment began circulating" during the nineteenth century.[93] An example is the claim that when the "Va, pensiero" chorus in Nabucco was first sung in Milan, the audience, responding with nationalistic fervour, demanded an encore. As encores were expressly forbidden by the government at the time, such a gesture would have been extremely significant. But in fact the piece encored was not "Va, pensiero" but the hymn "Immenso Jehova".[94][n 4]

The growth of the "identification of Verdi's music with Italian nationalist politics" perhaps began in the 1840s.[98] In 1848, the nationalist leader Giuseppe Mazzini (whom Verdi had met in London the previous year) requested Verdi (who complied) to write a patriotic hymn.[99] The opera historian Charles Osborne describes the 1849 La battaglia di Legnano as "an opera with a purpose" and maintains that "while parts of Verdi's earlier operas had frequently been taken up by the fighters of the Risorgimento...this time the composer had given the movement its own opera"[100] It was not until 1859 in Naples, and only then spreading throughout Italy, that the slogan "Viva Verdi" was used as an acronym for Viva Vittorio Emanuele Re D'Italia (Viva Victor Emmanuel King of Italy), (who was then king of Piedmont).[101] After Italy was unified in 1861, many of Verdi's early operas were increasingly re-interpreted as Risorgimento works with hidden Revolutionary messages that perhaps had not been originally intended by either the composer or his librettists.[102]

In 1859, Verdi was elected as a member of the new provincial council, and was appointed to head a group of five who would meet with King Vittorio Emanuele II in Turin. They were enthusiastically greeted along the way and in Turin Verdi himself received much of the publicity. On 17 October Verdi met with Cavour, the architect of the initial stages of Italian unification.[103] Later that year the government of Emilia was subsumed under the United Provinces of Central Italy, and Verdi's political life temporarily came to an end. Whilst still maintaining nationalist feelings, he declined in 1860 the office of provincial council member to which he had been elected in absentia.[104] Cavour however was anxious to convince a man of Verdi's stature that running for political office was essential to strengthening and securing Italy's future.[105] The composer confided to Piave some years later that "I accepted on the condition that after a few months I would resign."[106] Verdi was elected on 3 February 1861 for the town of Borgo San Donnino (Fidenza) to the Parliament of Piedmont-Sardinia in Turin (which from March 1861 became the Parliament of the Kingdom of Italy), but following the death of Cavour in 1861, which deeply distressed him, he scarcely attended.[107] Later, in 1874, Verdi was appointed a member of the Italian Senate, but did not participate in its activities.[108][109]

1860–1887: from La forza to Otello

In the months following the staging of Ballo, Verdi was approached by several opera companies seeking a new work or making offers to stage one of his existing ones, but refused them all.[110] But when, in December 1860, an approach was made from Saint Petersburg's Imperial Theatre, the offer of 60,000 francs plus all expenses was doubtless a strong incentive. Verdi came up with the idea of adapting the 1835 Spanish play Don Alvaro o la fuerza del sino by Angel Saavedra, which became La forza del destino, with Piave writing the libretto. The Verdis arrived in St. Petersburg in December 1861 for the premiere, but casting problems meant that it had to be postponed.[111]

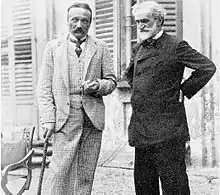

Returning via Paris from Russia on 24 February 1862, Verdi met two young Italian writers, the twenty-year-old Arrigo Boito and Franco Faccio. Verdi had been invited to write a piece of music for the 1862 International Exhibition in London, [112] and charged Boito with writing a text, which became the Inno delle nazioni. Boito, as a supporter of the grand opera of Giacomo Meyerbeer and an opera composer in his own right, was later in the 1860s critical of Verdi's "reliance on formula rather than form", incurring the composer's wrath. Nevertheless, he was to become Verdi's close collaborator in his final operas.[113] The St. Petersburg premiere of La forza finally took place in September 1862, and Verdi received the Order of St. Stanislaus.[114]

A revival of Macbeth in Paris in 1865 was not a success, but he obtained a commission for a new work, Don Carlos, based on the play Don Carlos by Friedrich Schiller. He and Giuseppina spent late 1866 and much of 1867 in Paris, where they heard, and did not warm to, Giacomo Meyerbeer's last opera, L'Africaine, and Richard Wagner's overture to Tannhäuser.[115] The opera's premiere in 1867 drew mixed comments. While the critic Théophile Gautier praised the work, the composer Georges Bizet was disappointed at Verdi's changing style: "Verdi is no longer Italian. He is following Wagner."[115]

During the 1860s and 1870s, Verdi paid great attention to his estate around Busseto, purchasing additional land, dealing with unsatisfactory (in one case, embezzling) stewards, installing irrigation, and coping with variable harvests and economic slumps.[116] In 1867, both Verdi's father Carlo, with whom he had restored good relations, and his early patron and father-in-law Antonio Barezzi, died. Verdi and Giuseppina decided to adopt Carlo's great-niece Filomena Maria Verdi, then seven years old, as their own child. She was to marry in 1878 the son of Verdi's friend and lawyer Angelo Carrara and her family became eventually the heirs of Verdi's estate.[117]

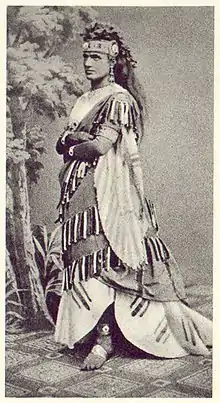

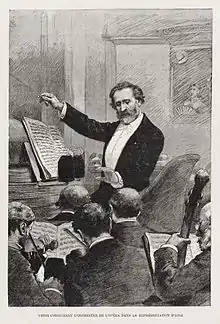

Aida was commissioned by the Egyptian government for the opera house built by the Khedive Isma'il Pasha to celebrate the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. The opera house actually opened with a production of Rigoletto. The prose libretto in French by Camille du Locle, based on a scenario by the Egyptologist Auguste Mariette, was transformed to Italian verse by Antonio Ghislanzoni.[118] Verdi was offered the enormous sum of 150,000 francs for the opera (even though he confessed that Ancient Egypt was "a civilization I have never been able to admire"), and it was first performed in Cairo in 1871.[119] Verdi spent much of 1872 and 1873 supervising the Italian productions of Aida at Milan, Parma and Naples, effectively acting as producer and demanding high standards and adequate rehearsal time.[120] During the rehearsals for the Naples production he wrote his string quartet, the only chamber music by him to survive, and the only major work in the form by an Italian of the 19th century.[121]

In 1869, Verdi had been asked to compose a section for a requiem mass in memory of Rossini. He compiled and completed the requiem, but its performance was abandoned (and its premiere did not take place until 1988).[122] Five years later, Verdi reworked his "Libera Me" section of the Rossini Requiem and made it a part of his Requiem honouring Alessandro Manzoni, who had died in 1873. The complete Requiem was first performed at the cathedral in Milan on the anniversary of Manzoni's death on 22 May 1874.[122] The spinto soprano Teresa Stolz (1834–1902), who had sung in La Scala productions from 1865 onwards, was the soloist in the first and many later performances of the Requiem; in February 1872, she had created Aida in its European premiere in Milan. She became closely associated personally with Verdi (exactly how closely remains conjectural), to Giuseppina Verdi's initial disquiet; but the women were reconciled and Stolz remained a companion of Verdi after Giuseppina's death in 1897 until his own death.[123]

Verdi conducted his Requiem in Paris, London and Vienna in 1875 and in Cologne in 1876.[108] It seemed that it would be his last work. In the words of his biographer John Rosselli, it "confirmed him as the unique presiding genius of Italian music. No fellow composer...came near him in popularity or reputation". Verdi, now in his sixties, initially seemed to withdraw into retirement. He deliberately shied away from opportunities to publicise himself or to become involved with new productions of his works,[124] but secretly he began work on Otello, which Boito (to whom the composer had been reconciled by Ricordi) had proposed to him privately in 1879. The composition was delayed by a revision of Simon Boccanegra which Verdi undertook with Boito, produced in 1881, and a revision of Don Carlos. Even when Otello was virtually completed, Verdi teased "Shall I finish it? Shall I have it performed? Hard to tell, even for me." As news leaked out, Verdi was pressed by opera houses across Europe with enquiries; eventually the opera was triumphantly premiered at La Scala in February 1887.[125]

1887–1901: Falstaff and last years

Following the success of Otello Verdi commented, "After having relentlessly massacred so many heroes and heroines, I have at last the right to laugh a little." He had considered a variety of comic subjects but had found none of them wholly suitable and confided his ambition to Boito. The librettist said nothing at the time but secretly began work on a libretto based on The Merry Wives of Windsor with additional material taken from Henry IV, Part 1 and Part 2.[126] Verdi received the draft libretto probably in early July 1889 after he had just read Shakespeare's play: "Benissimo! Benissimo!... No one could have done better than you", he wrote back to Boito. But he still had doubts: his age, his health (which he admits to being good) and his ability to complete the project: "If I were not to finish the music?". If the project failed, it would have been a waste of Boito's time, and have distracted him from completing his own new opera. Finally on 10 July 1889 he wrote again: "So be it! So let's do Falstaff! For now, let's not think of obstacles, of age, of illnesses!" Verdi emphasised the need for secrecy, but continued "If you are in the mood, then start to write."[127] Later he wrote to Boito (capitals and exclamation marks are Verdi's own): "What joy to be able to say to the public: HERE WE ARE AGAIN!!! COME AND SEE US!"[128]

The first performance of Falstaff took place at La Scala on 9 February 1893. For the first night, official ticket prices were thirty times higher than usual. Royalty, aristocracy, critics and leading figures from the arts all over Europe were present. The performance was a huge success; numbers were encored, and at the end the applause for Verdi and the cast lasted an hour. That was followed by a tumultuous welcome when the composer, his wife and Boito arrived at the Grand Hotel de Milan.[129] Even more hectic scenes ensued when he went to Rome in May for the opera's premiere at the Teatro Costanzi, when crowds of well-wishers at the railway station initially forced Verdi to take refuge in a tool-shed. He witnessed the performance from the Royal Box at the side of King Umberto and the Queen.[130]

_-_Archivio_storico_Ricordi_FOTO003107_-_Restoration.jpg.webp)

In his last years Verdi undertook a number of philanthropic ventures, publishing in 1894 a song for the benefit of earthquake victims in Sicily, and from 1895 onwards planning, building and endowing a rest-home for retired musicians in Milan, the Casa di Riposo per Musicisti, and building a hospital at Villanova sull'Arda, close to Busseto.[131][132] His last major composition, the choral set of Four sacred pieces, was published in 1898. In 1900 he was deeply upset at the assassination of King Umberto and sketched a setting of a poem in his memory but was unable to complete it.[133] While staying at the Grand Hotel, Verdi suffered a stroke on 21 January 1901.[n 5] He gradually grew more feeble over the next week, during which Stolz cared for him, and died on 27 January at the age of 87.[134][135]

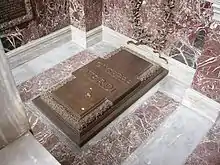

Verdi was initially buried in a private ceremony at Milan's Cimitero Monumentale.[136] A month later, his body was moved to the crypt of the Casa di Riposo. On this occasion, "Va, pensiero" from Nabucco was conducted by Arturo Toscanini with a chorus of 820 singers. A huge crowd was in attendance, estimated at 300,000.[137] Boito wrote to a friend, in words which recall the mysterious final scene of Don Carlos, "[Verdi] sleeps like a King of Spain in his Escurial, under a bronze slab that completely covers him."[138]

Personality

Not all of Verdi's personal qualities were amiable. John Rosselli concluded after writing his biography that "I do not very much like the man Verdi, in particular the autocratic rentier-cum-estate owner, part-time composer, and seemingly full-time grumbler and reactionary critic of the later years", yet admits that like other writers, he must "admire him, warts and all...a deep integrity runs beneath his life, and can be felt even when he is being unreasonable or wrong."[139]

Budden suggests that "With Verdi...the man and the artist on many ways developed side by side." Ungainly and awkward in society in his early years, "as he became a man of property and underwent the civilizing influence of Giuseppina,...[he] acquired assurance and authority."[140] He also learnt to keep himself to himself, never discussing his private life and maintaining when it suited his convenience legends about his supposed 'peasant' origins, his materialism and his indifference to criticism.[141] Gerald Mendelsohn describes the composer as "an intensely private man who deeply resented efforts to inquire into his personal affairs. He regarded journalists and would-be biographers, as well as his neighbors in Busseto and the operatic public at large, as an intrusive lot, against whose prying attentions he needed constantly to defend himself."[142]

Verdi was similarly never explicit about his religious beliefs. Anti-clerical by nature in his early years,[143] he nonetheless built a chapel at Sant'Agata, but is rarely recorded as going to church. Strepponi wrote in 1871 "I won't say [Verdi] is an atheist, but he is not much of a believer."[144] Rosselli comments that in the Requiem "The prospect of Hell appears to rule...[the Requiem] is troubled to the end," and offers little consolation.[145]

Music and form

See also List of compositions by Giuseppe Verdi and individual articles on the works.

Spirit

The writer Friedrich Schiller (four of whose plays were adapted as operas by Verdi) distinguished two types of artist in his 1795 essay On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry. The philosopher Isaiah Berlin ranked Verdi in the 'naïve' category—"They are not...self-conscious. They do not...stand aside to contemplate their creations and express their own feelings....They are able...if they have genius, to embody their vision fully." (The 'sentimentals' seek to recreate nature and natural feelings on their own terms—Berlin instances Richard Wagner—"offering not peace, but a sword".)[146] Verdi's operas are not written according to an aesthetic theory, or with a purpose to change the tastes of their audiences. In conversation with a German visitor in 1887 he is recorded as saying that, whilst "there was much to be admired in [Wagner's operas] Tannhäuser and Lohengrin...in his recent operas [Wagner] seemed to be overstepping the bounds of what can be expressed in music. For him "philosophical" music was incomprehensible."[147] Although Verdi's works belong, as Rosselli admits "to the most artificial of genres...[they] ring emotionally true: truth and directness make them exciting, often hugely so."[148]

Periods

The earliest study of Verdi's music, published in 1859 by the Italian critic Abraham Basevi, already distinguished four periods in Verdi's music. The early, 'grandiose' period, ended according to Basevi with La battaglia di Legnano (1849), and a 'personal' style began with the next opera Luisa Miller. These two operas are generally agreed today by critics to mark the division between Verdi's 'early' and 'middle' periods. The 'middle' period is felt to end with La traviata (1853) and Les vêpres siciliennes (1855), with a 'late' period commencing with Simon Boccanegra (1857) running through to Aida (1871). The last two operas, Otello and Falstaff, together with the Requiem and the Four Sacred Pieces, then represent a 'final' period.[149]

Early period

Verdi was to claim in his Sketch that during his early training with Lavigna "I did nothing but canons and fugues...No-one taught me orchestration or how to handle dramatic music."[150] He is known to have written a variety of music for the Busseto Philharmonic society, including vocal music, band music and chamber works,[151] (and including an alternative overture to Rossini's Barber of Seville)[152] but few of these works survive. (He may have given instructions before his death to destroy his early works).[153]

Verdi uses in his early operas (and, in his own stylized versions, throughout his later work) the standard elements of Italian opera content of the period, referred to by the opera writer Julian Budden as the 'Code Rossini', after the composer who established through his work and popularity the accepted templates of these forms; they were also used by the composers dominant during Verdi's early career, Bellini, Donizetti and Saverio Mercadante. Amongst the essential elements are the aria, the duet, the ensemble, and the finale sequence of an act.[154] The aria format, centred on a soloist, typically involved three sections; a slow introduction, marked typically cantabile or adagio, a tempo di mezzo which might involve chorus or other characters, and a cabaletta, an opportunity for bravura singing for the soloist. The duet was similarly formatted. Finales, covering climactic sequences of action, used the various forces of soloists, ensemble and chorus, usually culminating with an exciting stretto section. Verdi was to develop these and the other formulae of the generation preceding him with increasing sophistication during his career. [155][156]

The operas of the early period show Verdi learning by doing and gradually establishing mastery over the different elements of opera. Oberto is poorly structured, and the orchestration of the first operas is generally simple, sometimes even basic.[157] The musicologist Richard Taruskin suggests "the most striking effect in the early Verdi operas, and the one most obviously allied to the mood of the Risorgimento, was the big choral number sung—crudely or sublimely, according to the ear of the beholder—in unison. The success of "Va, pensiero" in Nabucco (which Rossini approvingly denoted as "a grand aria sung by sopranos, contraltos, tenors and basses"), was replicated in the similar "O Signor, dal tetto natio" in I lombardi and in 1844 in the chorus "Si ridesti il Leon di Castiglia" in Ernani, the battle hymn of the conspirators seeking freedom[158][159] In I due Foscari Verdi first uses recurring themes identified with main characters; here and in future operas the accent moves away from the 'oratorio' characteristics of the first operas towards individual action and intrigue.[157]

From this period onwards Verdi also develops his instinct for "tinta" (literally 'colour'), a term which he used for characterising elements of an individual opera score—Parker gives as an example "the rising 6th that begins so many lyric pieces in Ernani".[160] Macbeth, even in its original 1847 version, shows many original touches; characterization by key (the Macbeths themselves generally singing in sharp keys, the witches in flat keys),[160] a preponderance of minor key music, and highly original orchestration. In the 'dagger scene' and the duet following the murder of Duncan, the forms transcend the 'Code Rossini' and propel the drama in a compelling fashion.[161] Verdi was to comment in 1868 that Rossini and his followers missed "the golden thread that binds all the parts together and, rather than a set of numbers without coherence, makes an opera". Tinta was for Verdi this "golden thread", an essential unifying factor in his works.[162]

Middle period

The writer David Kimbell states that in Luisa Miller and Stiffelio (the earliest operas of this period) there appears to be a "growing freedom in the large scale structure...and an acute attention to fine detail".[42] Others echo those feelings. Julian Budden expresses the impact of Rigoletto and its place in Verdi's output as follows: "Just after 1850 at the age of 38, Verdi closed the door on a period of Italian opera with Rigoletto. The so-called ottocento in music is finished. Verdi will continue to draw on certain of its forms for the next few operas, but in a totally new spirit."[163] One example of Verdi's wish to move away from "standard forms" appears in his feelings about the structure of Il trovatore. To his librettist, Cammarano, Verdi plainly states in a letter of April 1851 that if there were no standard forms—"cavatinas, duets, trios, choruses, finales, etc. ... and if you could avoid beginning with an opening chorus....", he would be quite happy. [164]

Two external factors had their impacts on Verdi's compositions of this period. One is that with increasing reputation and financial security he no longer needed to commit himself to the productive treadmill, had more freedom to choose his own subjects, and had more time to develop them according to his own ideas. In the years 1849 to 1859 he wrote eight new operas, compared with fourteen in the previous ten years.[74]

Another factor was the changed political situation; the failure of the 1848 revolutions led both to some diminution of the Risorgimento ethos (at least initially) and a significant increase in theatre censorship.[74] This is reflected both in Verdi's choices of plots dealing more with personal relationships than political conflict, and in a (partly consequent) dramatic reduction in the operas of this period in the number of choruses (of the type which had first made him famous)—not only are there on average 40% fewer choruses in the 'middle' period operas compared to the 'early' period', but whereas virtually all the 'early' operas commence with a chorus, only one (Luisa Miller) of the 'middle' period operas begin this way. Instead, Verdi experiments with a variety of means, e.g. a stage band (Rigoletto), an aria for bass (Stiffelio), a party scene (La traviata). Chusid also notes Verdi's increasing tendency to replace full-scale overtures with shorter orchestral introductions.[165] Parker comments that La traviata, the last opera of the 'middle' period, is "again a new adventure. It gestures towards a level of 'realism'...the contemporary world of waltzes pervades the score, and the heroine's death from disease is graphically depicted in the music."[166] Verdi's increasing command of musical highlighting of changing moods and relationships is exemplified in Act III of Rigoletto, where Duke's flippant song "La donna è mobile" is followed immediately by the quartet "Bella figlia dell'amore", contrasting the rapacious Duke and his inamorata with the (concealed) indignant Rigoletto and his grieving daughter. Taruskin asserts this is "the most famous ensemble Verdi ever composed".[167]

Late period

Chusid notes Strepponi's description of the operas of the 1860s and 1870s as being "modern" whereas Verdi described the pre-1849 works as "the cavatina operas", as further indication that "Verdi became increasingly dissatisfied with the older, familiar conventions of his predecessors that he had adopted at the outset of his career,"[168] Parker sees a physical differentiation of the operas from Les vêpres siciliennes (1855) to Aida (1871) is that they are significantly longer, and with larger cast-lists, than previous works. They also reflect a shift towards the French genre of grand opera, notable in more colorful orchestration, counterpointing of serious and comic scenes, and greater spectacle.[169] The opportunities of transforming Italian opera by utilising such resources appealed to him. For a commission from the Paris Opéra he expressly demanded a libretto from Eugène Scribe, the favorite librettist of Meyerbeer, telling him: "I want—in fact, I must have—a grandiose, impassioned and original subject." The result was Les vêpres siciliennes, and the scenarios of Simon Boccanegra (1857), Un ballo in maschera (1859), La forza del destino (1862), Don Carlos (1865) and Aida (1872) all meet the same criteria. Porter notes that Un ballo marks an almost complete synthesis of Verdi's style with the grand opera hallmarks, such that "huge spectacle is not mere decoration but essential to the drama...musical and theatrical lines remain taut [and] the characters still sing as warmly, passionately and personally as in Il trovatore."[170]

When the composer Ferdinand Hiller asked Verdi whether he preferred Aida or Don Carlos, Verdi replied that Aida had "more bite and (if you'll forgive the word), more theatricality".[171] During the rehearsals for the Naples production of Aida Verdi amused himself by writing his only string quartet, a sprightly work which shows in its last movement that he had not lost the skill for fugue-writing that he had learned with Lavigna.[172]

Final works

Verdi's three last major works continued to show new development in conveying drama and emotion. The first to appear, in 1874 was his Requiem, scored for operatic forces but by no means an "opera in ecclesiastical dress" (the words in which Hans von Bülow condemned it before even hearing it).[173] Although in the Requiem Verdi puts to use many of the techniques he learned in opera, its musical forms and emotions are not those of the stage.[174] Verdi's tone painting at the opening of the Requiem is vividly described by the Italian composer Ildebrando Pizzetti, writing in 1941: "in [the words] murmured by an invisible crowd over the slow swaying of a few simple chords, you straightaway sense the fear and sadness of a vast multitude before the mystery of death. In the [following] Et lux perpetuum the melody spreads it wings...before falling back on itself...you hear a sigh for consolation and eternal peace."[175]

By the time Otello premièred in 1887, more than 15 years after Aida, the operas of Verdi's (predeceased) contemporary Richard Wagner had begun their ascendancy in popular taste, and many sought or identified Wagnerian aspects in Verdi's latest composition.[176] Budden points out that there is little in the music of Otello that relates either to the verismo opera of the younger Italian composers, and little if anything which can be construed as a homage to the New German School.[177] Nonetheless there is still much originality, building on the strengths which Verdi had already demonstrated; the powerful storm which opens the opera in medias res, the recollection of the love duet of Act I in Otello's dying words (more an aspect of tinta than leitmotif), imaginative touches of harmony in Iago's "Era la notte" (Act II).[178]

Finally, six years later, appeared Falstaff, Verdi's only comedy apart from the early, ill-fated Un giorno di regno. In this work Roger Parker writes that:

- "the listener is bombarded by a stunning diversity of rhythms, orchestral textures, melodic motifs and harmonic devices. Passages that in earlier times would have furnished material for an entire number here crowd in on each other, shouldering themselves unceremoniously to the fore in bewildering succession".[179] Rosselli comments: "In Otello Verdi had miniaturized the forms of romantic Italian opera; in Falstaff he miniaturized himself...[M]oments...crystallize a feeling...as though an aria or duet had been precipitated into a phrase."[180]

Legacy

Reception

Although Verdi's operas brought him a popular following, not all contemporary critics approved of his work. The English critic Henry Chorley allowed in 1846 that "he is the only modern man...having a style—for better or worse", but found all his output unacceptable. "[His] faults [are] grave ones, calculated to destroy and degrade taste beyond those of any Italian composer in the long list" wrote Chorley, whilst conceding that "howsoever incomplete may have been his training, howsoever mistaken his aspirations may have proved...he has aspired."[181] But by the time of Verdi's death, 55 years later, his reputation was assured, and the 1910 edition of Grove's Dictionary pronounced him "one of the greatest and most popular opera composers of the nineteenth century".[182]

Verdi had no pupils apart from Muzio and no school of composers sought to follow his style which, however much it reflected his own musical direction, was rooted in the period of his own youth. By the time of his death, verismo was the accepted style of young Italian composers. [183] The New York Metropolitan Opera frequently staged Rigoletto, Trovatore and Traviata during this period and featured Aida in every season from 1898 to 1945. Interest in the operas reawakened in mid-1920s Germany and this sparked a revival in England and elsewhere. From the 1930s onward there began to appear scholarly biographies and publications of documentation and correspondence.[184]

In 1959 the Instituto di Studi Verdiani (from 1989 the Istituto Nazionale di Studi Verdiani) was founded in Parma and became a leading centre for research and publication of Verdi studies,[185] and in the 1970s the American Institute for Verdi Studies was founded at New York University.[186][187]

Nationalism in the operas

Historians have debated how political Verdi's operas were. In particular, the Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves (known as Va, pensiero) from the third act of the opera Nabucco was used an anthem for Italian patriots, who were seeking to unify their country and free it from foreign control in the years up to 1861 (the chorus's theme of exiles singing about their homeland, and its lines such as O mia patria, si bella e perduta / "O my country, so lovely and so lost" were thought to have resonated with many Italians).[188] Beginning in Naples in 1859 and spreading throughout Italy, the slogan "Viva VERDI" was used as an acronym for Viva Vittorio Emanuele Re D'Italia (Long live Victor Emmanuel King of Italy), referring to Victor Emmanuel II.[189][190] Marco Pizzo argues that after 1815, music became a political tool, and many songwriters expressed ideals of freedom and equality. Pizzo claims that Verdi was part of this movement, for his operas were inspired by the love of country, the struggle for Italian independence, and speak to the sacrifice of patriots and exiles.[191] George Martin claims Verdi was "the greatest artist" of the Risorgimento. "Throughout his work its values, its issues recur constantly, and he expressed them with great power".[192]

But Mary Ann Smart argues that music critics at the time seldom mentioned any political themes.[193][194] Likewise, Roger Parker argues that the political dimension of Verdi's operas was exaggerated by nationalistic historians looking for a hero in the late 19th century.[195]

From the 1850s onwards, Verdi's operas displayed few patriotic themes because of the heavy censorship by the absolutist regime in power. Verdi later became disillusioned by politics, but he was personally active part in the political world of events of the Risorgimento and was elected to the first Italian parliament in 1861.[196]

Memorials and cultural portrayals

Three Italian conservatories, the Milan Conservatory[197] and those in Turin[198] and Como,[199] are named after Verdi, as are many Italian theatres.

Verdi's hometown of Busseto displays Luigi Secchi's statue of a seated Verdi in 1913, next to the Teatro Verdi built in his honour in the 1850s.[200] It is one of many statues to the composer in Italy.[201] The Giuseppe Verdi Monument, a 1906 marble memorial, sculpted by Pasquale Civiletti, is located in Verdi Square in Manhattan, New York City. The monument includes a statue of Verdi himself and life-sized statues of four characters from his operas, (Aida, Otello, and Falstaff from the operas of the same names, and Leonora from La forza del destino).[202]

Verdi has been the subject of a number of film and stage works. These include the 1938 film directed by Carmine Gallone, Giuseppe Verdi, starring Fosco Giachetti;[203] the 1982 miniseries, The Life of Verdi, directed by Renato Castellani, where Verdi was played by Ronald Pickup, with narration by Burt Lancaster in the English version;[204] and the 1985 play After Aida, by Julian Mitchell (1985).[205] He is a character in the 2011 opera Risorgimento! by Italian composer Lorenzo Ferrero, written to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Italian unification of 1861.[206]

Verdi today

Verdi's operas are frequently staged around the world.[43] All of his operas are available in recordings in a number of versions,[207] and on DVD – Naxos Records offers a complete boxed set.[208]

Modern productions may differ substantially from those originally envisaged by the composer. Jonathan Miller's 1982 version of Rigoletto for English National Opera, set in the world of modern American mafiosi, received critical plaudits.[209] But the same company's staging in 2002 of Un ballo in maschera as A Masked Ball, directed by Calixto Bieito, including "satanic sex rituals, homosexual rape, [and] a demonic dwarf", got a general critical thumbs down.[210]

Meanwhile, the music of Verdi can still evoke a range of cultural and political resonances. Excerpts from the Requiem were featured at the funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales in 1997.[137] On 12 March 2011 during a performance of Nabucco at the Opera di Roma celebrating 150 years of Italian unification, the conductor Riccardo Muti paused after "Va pensiero" and turned to address the audience (which included the then Italian Prime Minister, Silvio Berlusconi) to complain about cuts in state funding of culture; the audience then joined in a repeat of the chorus.[211][212] In 2014, the pop singer Katy Perry appeared at the Grammy Award wearing a dress designed by Valentino, embroidered with the music of "Dell'invito trascorsa è già l'ora" from the start of La traviata.[213] The bicentenary of Verdi's birth in 2013 was celebrated in numerous events around the world, both in performances and broadcasts.[214]

Notes

- In 1880 he was upgraded to Grand Officer of the Legion, after the Paris premiere of Aida.[50] In 1894, after the Paris premiere of Falstaff he was awarded the Grand Croix of the Legion.[51]

- Taruskin comments: "Its eventual success was almost too great, since many...ascribe...to [the opera] or even to Verdi the song's trivial gaiety without realizing that its brashness was a calculated ironic foil."[65]

- After Falstaff, Boito commented to Verdi "Now, maestro, we must set to work on King Lear" (for which Boito had prepared a draft), but Giuseppina was horrified at this prospect: "For heaven's sake, Boito, Verdi is too old, too tired"[76] In 1896, Verdi offered his Lear materials to Pietro Mascagni who asked "Maestro, why didn't you put it into music?" According to Mascagni, "softly and slowly he replied, 'the scene in which King Lear finds himself on the heath scared me'".[77]

- Although the story of the encore of "Va pensiero" has been demonstrated to be untrue, research indicates that the chorus did indeed have a resonance for supporters of the Risorgimento,[95][96] and beyond: as recently as 2009 it was proposed to adopt the chorus as Italy's national anthem.[97]

- The hotel's website (accessed 14 June 2015) contains a brief history of the composer's stay

References

Citations

- Parker n.d., §2.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 12.

- Phillips-Matz 2004, p. 4.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 14.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 17–21.

- Parker 1998, p. 933.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 20–21.

- Kimbell 1981, p. 92.

- Parker 2007, pp. 2–3.

- Parker n.d., §3.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 27–30.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 32.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 35.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 46.

- Parker 2007, p. 1.

- Werfel & Stefan 1973, pp. 80–93.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 67.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 79–80.

- Kimbell 1981, pp. 92, 96.

- Budden 1993, p. 71.

- Budden 1993, p. 16.

- Werfel & Stefan 1973, pp. 87–92.

- Porter 1980, pp. 638–39.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 181.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 379.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 139.

- Budden 1984a, p. 116.

- Porter 1980, p. 649.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 160–61.

- Budden 1993, p. 45.

- "Story" on Villa Verdi website, accessed 10 June 2015.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 148.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 150–51.

- Kerman 2006, p. 23.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 52.

- Parker n.d., §4.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 160.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 166.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 192–93.

- Marchesi n.d.

- Werfel & Stefan 1973, p. 122.

- Chusid 1997, p. 1.

- Operabase website, accessed 28 June 2015.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 196.

- Baldini 1980, p. 132.

- Budden 1984a, pp. 318–19.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 229–41.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 63.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 72.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 180.

- Reibel 2001, p. 97.

- Budden 1984a, p. 365.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 229.

- Martin 1984, p. 220.

- Osborne 1969, p. 189.

- Budden 1984a, p. 390.

- Rosselli 2000, pp. 79–80.

- Walker 1962, p. 194.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 89.

- Newark 2004, p. 198.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 90–91.

- Rosselli 2000, pp. 92–93.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 101.

- Taruskin 2010, p. 585.

- Taruskin 2010, p. 586.

- Walker 1962, pp. 197–98.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 287.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 290.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 289–.

- Kerman 2006, pp. 22–23.

- Walker 1962, p. 199.

- Budden 1984b, p. 63.

- Budden 1993, p. 54.

- Chusid 1997, p. 3.

- Budden 1993, pp. 70–71.

- Budden 1993, p. 138.

- Mendelsohn 1979, p. 223.

- Mendelsohn 1979, p. 226.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 303.

- Walker 1962, p. 212.

- Budden 1993, pp. 62–63.

- Parker 1982, p. 155.

- Parker n.d., §5.

- Walker 1962, p. 218.

- Walker 1962, p. 219.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 355.

- Werfel & Stefan 1973, p. 207.

- Rosselli 2000, pp. 116–17.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 394.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 70.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 405.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 412–15.

- Gossett 2012, pp. 272, 274.

- Gossett 2012, pp. 272, 275–76.

- Gossett 2005.

- Author's summary of Gossett (2005), accessed 18 July 2015.

- Anna Momigliano, "Senator wants to change Italy's national anthem – to opera", Christian Science Monitor, 24 August 2009, accessed 18 July 2015

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 188–91.

- Gossett 2012, pp. 279–80.

- Osborne 1969, p. 198.

- Budden 1984c, p. 80.

- Gossett 2012, p. 272.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 400–02.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 417.

- Gossett 2012, p. 281.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 429–30.

- Gossett 2012, p. 282.

- Porter 1980, p. 653.

- "Senato del Regno" (in Italian) (340). Gazzetta Piemontese. 10 December 1874.

(Article stating the Italian Senate voted to approve Verdi's nomination on 8 Nov. 1874)

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 439–46.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 124.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 446–49.

- Parker 2007, pp. 3–4.

- Budden 1993, p. 88.

- Budden 1993, p. 93.

- Rosselli 2000, pp. 128–31.

- Rosselli 2000, pp. 131, 133.

- Porter 1980, p. 655.

- Rosselli 2000, pp. 149–50.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 158–159.

- Stowell 2003, p. 259.

- Rosselli 2000, pp. 138–39.

- Christiansen 1995, pp. 202–03.

- Rosselli 2000, pp. 163–65.

- Rosselli 2000, pp. 164–72.

- Klein 1926, p. 606.

- Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 700–01.

- Mendelsohn 1978, p. 122.

- Hepokoski 1983, pp. 55–56.

- Budden 1993, p. 137.

- Budden 1993, p. 140.

- Parker n.d., §8.

- Budden 1993, pp. 143–44.

- Budden 1993, p. 146.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 186.

- Porter 1980, p. 659.

- Phillips-Matz 2004, p. 14.

- Walker 1962, p. 509.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 7.

- Budden 1993, pp. 148–49.

- Budden 1993, p. 153.

- Mendelsohn 1978, p. 110.

- Budden 1993, pp. 2–3, 9–10.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 161.

- Rosselli 2000, pp. 162–63.

- Berlin 1979, pp. 3–4.

- Conati 1986, p. 147.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 1.

- Porter 1980, p. 639.

- Porter 1980, p. 636.

- Porter 1980, p. 637.

- Budden 1993, p. 5.

- Gossett 2008, p. 161.

- Taruskin 2010, pp. 15–16.

- Balthazar 2004, pp. 49–59.

- Parker n.d., §4 (ii).

- Parker n.d., §4 (vii).

- Taruskin 2010, pp. 570–75.

- Budden 1993, p. 21.

- Parker n.d., §4 (iv).

- Budden 1993, pp. 190–92.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 95.

- Budden 1984a, p. 510.

- Budden 1984b, p. 61.

- Chusid 1997, pp. 9–11.

- Parker n.d., §4 (vi).

- Taruskin 2010, p. 587.

- Chusid 1997, p. 2.

- Parker n.d., §6 (i).

- Porter 1980, pp. 653–55.

- Budden 1993, p. 272.

- Budden 1993, pp. 310–11.

- Parker n.d., §7.

- Rosselli 2000, pp. 161–62.

- Budden 1993, p. 320.

- Taruskin 2010, pp. 602–03.

- Budden 1993, p. 281.

- Budden 1993, pp. 282–84.

- Parker 1998, p. 229.

- Rosselli 2000, p. 182.

- Chorley 1972, pp. 182, 185–6.

- Mazzucato 1910, p. 247.

- Parker n.d., §10 (ii).

- Harwood 2004, p. 272.

- "Who we are" website of the Istituto di studi verdiani, accessed 27 June 2015.

- "American Institute for Verdi Studies" at NYU website, accessed 27 June 2015.

- Harwood 2004, p. 273.

- "Modern History Sourcebook: Music and Nationalism". Fordham.edu. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- Parker 1998, p. 942

- Budden 1973, Vol. 3, p. 80

- Marco Pizzo, "Verdi, Musica e Risorgimento," Rassegna Storica del Risorgimento (2001) 87 supplement 4 pp. 37–44

- George Whitney Martin (1988). Aspects of Verdi. Limelight Editions. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-87910-172-5.

- Mary Ann Smart, "Verdi, Italian Romanticism, and the Risorgimento," in Scott L. Balthazar (2004). The Cambridge Companion to Verdi. Cambridge UP. pp. 29–45. ISBN 978-0-521-63535-6.

- Mary Ann Smart, "How political were Verdi's operas? Metaphors of progress in the reception of I Lombardi alla prima crociata," Journal of Modern Italian Studies (2013) 18#2 pp. 190–204.

- Roger Parker, "Verdi politico: a wounded cliché regroups." Journal of Modern Italian Studies 17#4 (2012): 427–36.

- Franco DellaPeruta, "Verdi e il Risorgimento," Rassegna Storica del Risorgimento (2001) 88#1 pp. 3–24

- "Storia", Milan Conservatory website, accessed 27 June 2015.

- Conservatorio Statale di Musica Giuseppe Verdi, Torino website, accessed 27 June 2015

- Conservatorio di musica "Giuseppe Verdi" of Como website, accessed 27 June 2015

- Sadie & Sadie 2005, p. 385.

- A number of photographs of these can be seen at the "Opera, My Love" website (accessed 27 June 2015).

- "Verdi Memorial, (sculpture)".

- Giuseppe Verdi in IMDb website, accessed 27 June 2015.

- Verdi (1982) in IMDb website, accessed 27 June 2015.

- After Aida Archived 30 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine production details at Robert Fox Ltd. website, accessed 27 June 2015.

- Risorgimento on website of Teatro Comunale di Bologna, accessed 27 June 2015.

- See e.g. Opera Discography Encyclopedia website, accessed 28 June 2015.

- "Tutto Verdi", Naxos website, accessed 28 June 2015

- See. e.g. John O'Connor, "Jonathan Miller's Mafia 'Rigoletto'", The New York Times, 23 February 1989, accessed 28 June 2015.

- Matt Slater, "Revamped opera fails to shock", BBC News website, 22 February 2002, accessed 28 June 2015.

- James Bone, "Against Silvio Berlusconi's idea of culture", The Australian, 24 March 2011, accessed 28 June 2015.

- See "Va, pensiero", YouTube, accessed 28 June 2015.

- "Katy Perry's Verdi dress steals show at Grammys", 28 January 2014, on Classic FM website, accessed 28 June 2015

- Charlotte Runcie, "Verdi: How his 200th birthday is being celebrated", Daily Telegraph, 9 October 2013, accessed 13 July 2015

Sources

- Baldini, Gabriele (1980). The Story of Giuseppe Verdi: Oberto to Un Ballo in Maschera. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29712-7.

- Balthazar, Scott E. (2004), "The forms of set pieces", in Balthazar, Scott E. (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Verdi, Cambridge Companions to Music, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 49–68, ISBN 978-0-521-63535-6

- Berlin, Isaiah (6 October 1979). "The 'Naiveté' of Verdi". New Republic. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- Budden, Julian (1984a). The Operas of Verdi, Volume 1 (3rd ed.). London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-19-816262-9.

- Budden, Julian (1984b). The Operas of Verdi, Volume 2 (3rd ed.). London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-19-816262-9.

- Budden, Julian (1984c). The Operas of Verdi, Volume 3 (3rd ed.). London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-19-816263-6.

- Budden, Julian (1993). Verdi (Master Musicians series) (revised ed.). London: J.M. Dent. ISBN 978-0-460-86111-3.

- Chorley, Henry F. (1972). Thirty Years' Musical Recollections. New York: Vienna House. ISBN 978-0-8443-0026-9.

- Christiansen, Rupert (1995). Prima Donna: A History (revised and updated ed.). London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-712-67466-9.

- Chusid, Martin (1997), "Towards an Understanding of Verdi's Middle Period", in Chusid, Martin (ed.), Verdi's Middle Period, 1849 to 1859, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, pp. 1–14, ISBN 978-0-226-10659-5

- Conati, Marcello (ed.) (1986). Encounters with Verdi. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-801-49430-7.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Gossett, Philip (2005), "Edizioni distrutte and the Significance of Operatic Choruses during the Risorgimento", in Johnson, Victoria (ed.), Opera and Society in Italy and France from Monteverdi to Bourdieu, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 339–87, ISBN 978-0-521-12420-1

- Gossett, Philip (2008). Divas and Scholars: Performing Italian Opera. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-30488-5.

- Gossett, Philip (2012). "Giuseppe Verdi and the Italian Risorgimento (Jayne Lecture, 2010)" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 156 (3): 271–82. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Harwood, Gregory W. (2004), "Verdi criticism", in Balthazar, Scott E. (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Verdi, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 269–81, ISBN 978-0-521-63535-6

- Hepokoski, James (1983). Giuseppe Verdi "Falstaff". Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23534-1.

- Kerman, Joseph (2006). "Verdi and the Undoing of Women". Cambridge Opera Journal. 18 (1): 21–31. doi:10.1017/S0954586706002072. JSTOR 3878271. (subscription required)

- Kimbell, David R. B. (1981). Verdi in the Age of Italian Romanticism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31678-1.

- Klein, John W. (July 1926). "Verdi and Falstaff". Musical Times. 67 (1001): 605–07. doi:10.2307/911833. JSTOR 911833. (subscription required)

- Marchesi, Gustavo (n.d.). "Muzio [Mussio], (Donnino) Emanuele". Oxford Music Online (online ed.). Retrieved 14 July 2015.(subscription required)

- Martin, George (1984). Verdi: His Music, Life and Times. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. ISBN 978-0-396-08196-8.

- Mazzucato, Giannandrea (1910), "Verdi, Giuseppe", in Fuller Maitland, J.A. (ed.), Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 5 (2nd ed.), New York: Macmillan, pp. 247–60

- Mendelsohn, Gerald A. (1978). "Verdi the Man and Verdi the Dramatist". 19th-Century Music. University of California Press. 2 (2): 110–42. doi:10.2307/746308. JSTOR 746308. (subscription required)

- Mendelsohn, Gerald A. (1979). "Verdi the Man and Verdi the Dramatist (II)". 19th-Century Music. University of California Press. 2 (3): 214–30. doi:10.2307/3519798. JSTOR 3519798. (subscription required)

- Newark, Cormac (2004), ""Ch'hai di nuovo, buffon?" or What's new with "Rigoletto"", in Balthazar, Scott E. (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Verdi, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 197–208, ISBN 978-0-521-63535-6

- Osborne, Charles (1969). The Complete Opera of Verdi. New York: Da Capo Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-306-80072-6.

- Parker, Roger (1982). "The Dramatic Structure of 'Il trovatore'". Music Analysis. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1 (2): 155–67. doi:10.2307/854126. JSTOR 854126. (subscription required)

- Parker, Roger (1998), "Verdi, Giuseppe", in Sadie, Stanley (ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, 4, London: Macmillan Publishers, ISBN 978-0-333-73432-2

- Parker, Roger (2007). "Verdi and Milan". Lectures and Events. Gresham College. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- Parker, Roger (n.d.). "Verdi, Giuseppe". Oxford Music Online (online ed.). Retrieved 9 June 2015. (subscription required)

- Phillips-Matz, Mary Jane (1993). Verdi: A Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-313204-7.

- Phillips-Matz, Mary Jane (2004), "Verdi's life: a thematic biography", in Balthazar, Scott E. (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Verdi, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–14, ISBN 978-0-521-63535-6